Unsex Me Here: How Removing Markers of Eroticism Alters the Status of the Female Nude

BY MARY GERHARDINGER, KENYON COLLEGE

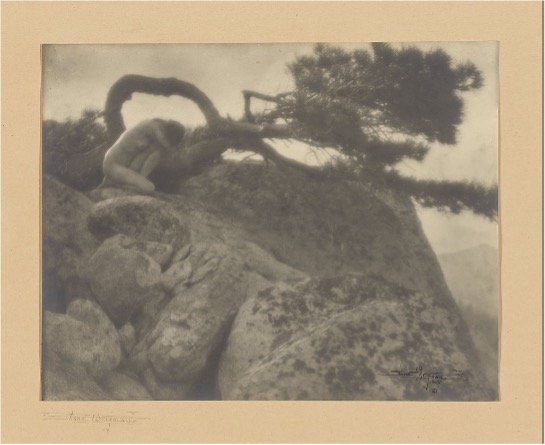

Atop a pile of boulders, an unclothed figure sits at the base of a tree. The tree’s upper branch reaches across the top part of the frame—the curve of the bough mimicked in the hunched shoulders of the human shape. The figure, with limbs folded so as to obscure their identity, blends in with the background rocks in both color and size. The stones dominate the composition; there is but a hint of geographical space suggested on the right side of the arrangement through a small, light, triangular shape indicative of a mountain in the distance. Although the figure is nude, the human body is not sexed, an important fact once we learn the shape is a woman. Given the context of the female nude in art history, why is this representation of a bare feminine body in nature uneroticized? What is the impact of treating the figure as part of the landscape?

Figure 1

An answer to these questions can be found within the biography of the artist, Anne Brigman, who is herself the sitter of this piece, entitled The Lone Pine (Figure 1).2 A photographer and poet, Brigman is celebrated as “one of the first photographers to take the female nude in the natural landscape as a subject,” as opposed to an object in an indoor space.3 Brigman’s unclothed photographs of herself complicate the representation of the female nude as a trope in art history. In this article, I will examine how Brigman represented the feminine body through an investigation of how she celebrated her own feminine form as human rather than female. By focusing on the form’s humanity and emotional struggle as a universal experience, Brigman elevates the status of all women away from sexual objects. However, she also places the figures in an imagined space, and thus contextualizes their power as fictitious, thereby eroding their authority—yet also separating the bodies from a set of Western cultural values. In this way, I claim that her pieces are less about elevating female bodies as feminine and more about expressing a collective human identity of struggle and emotion.

First, we must examine a popular use of the female nude throughout art history, to understand how the feminine form has dominated portraiture. The use of the feminine body as an allegory for abstract ideas is a pervasive and oft-imposed concept in art making. Eugene Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People (Figure 2), for instance, famously personifies liberty as a partially clothed woman grasping the French flag in a call to action. Art seems to insist upon the unclothed feminine figure as the way to represent nonrepresentational concepts. Following in this tradition, Brigman’s nude compositions further enforce this connection between the female nude and allegories, maintaining the status of the feminine figure as a tool rather than a person. On the other hand, these personified ideas usually employ ‘idealized’ bodies, which conform to beauty standards of the time (a tradition continued from the time of the Greeks). Brigman, however, alters this idea by inserting her own body in place of the idealized feminine form. Despite having one of her breasts surgically removed after an injury, Brigman still chose to represent her body—something less than the ‘ideal.’4 Thus, while she continues to use the feminine figure as a tool for personification, Brigman challenges the idea of perfection and ideality.

Figure 2

To what extent, however, did Brigman intend for her compositions to alter the allegorical representational aspect of the female nude and instead highlight femininity in and of itself? There are many possible motivations for the creations of these photographs—as celebrations of femininity and feminine sexuality, explorations of personal ideas on emotional struggle manifested physically, or even simply investigations into formalist concerns of incorporating a figure into a landscape. Brigman took inspiration from the photographer Frank Eugene who manipulated photographs of women by “rubbing oil onto the negatives with his fingers and adding cross hatching with an etching needle [...] leaving only small portions of a picture recognizably photographic.”6 Similarly to Eugene, Brigman claimed that she sought not only to represent her subjects but also to “deal honestly with the medium” of photography.7 She was moved by Eugene’s productions and incorporated the method of retouching negatives to execute her artistic vision. Brigman viewed manipulation as “necessary to secure the result she ha[d] in mind.”8 Through her investigations of the feminine form as representative of a universal struggle for freedom, Brigman used her own female body to “evoke an imagined feminine sexuality.”9 In doing so, art historian Kathleen Pyne argues that Anne Brigman taught Alfred Stieglitz, the leader of the Photo Secessionists, how to more properly portray women naked.10 These representations indicate that Brigman was consciously thinking about how to portray feminine sexuality in a variety of contexts, both imagined and physical.

The fact that Brigman situates her nudes in nature, or “wilderness,” further complicates the idea of expressing feminine sexuality in a purely positive or negative manner. The concept of wilderness has a complicated history within North American settler colonialism. By presenting land as untamed and yet controllable, the term has been used as a means to suppress Indigenous people. Within that context, wilderness was often portrayed as feminine and described as ‘virginal,’ eliciting both ideas of purity and the ability to be managed.11 Colloquial references like those to ‘mother nature,’ further link femininity and the environment—emphasizing nature’s procreative and nurturing characteristics as inherently feminine. In situating her nudes within ‘wilderness,’ Brigman is connecting nature and primalcy to female sexuality and, at the same time, reclaiming the power of nature to suggest strength in femininity. The placement of the nudes in nature, then, neither elevates nor suppresses feminine sexuality—suggesting that Brigman’s intent was merely to use female bodies as a form through which to explore her own emotional struggles.

Audience reception, however, is never fully aligned with artistic intent. Public reactions to exhibitions of Brigman’s work from 1904-1924 were varied, although they focused mostly around the incorporation of the body into a natural environment.3 In the first critical piece of Brigman’s photographs in the journal of the Photo Secessionists, J. Nilson Laurvik writes that in her work “the human is not an alien...wherein all that nature holds of sheer beauty, of terror or mystery achieves its fitting crescendo.” 12 Many other critics echo this emotional connection to Brigman’s photographs, claiming to “grasp the very soul of nature” through them.13 These reactions exemplify how, at the time, Brigman’s work was considered in two contexts: both as depicting a subject in relation to nature as well as expressing her own emotional struggle. Importantly, Brigman herself strove to “produce photographs that underscored her deeply held beliefs about the interconnectedness between humans and the natural environment.”14 Although critics responded well to Brigman’s themes of interrelation, not every audience has felt an emotional resonance with the work. Historically, some pieces have been “dismissed as unabashedly romantic, dramatically staged, or overly idealistic” because Brigman’s idea of representing her own body in nature was radical for the time.15

Figure 3

After the initial reaction of shock due to the radicality of these compositions, art historians have also viewed Brigman as a proto-feminist, who laid the groundwork for ecofeminist art. Art historian Ann Wolfe examines Brigman’s use of the female nude through the lens of feminism and draws connections between Brigman’s proto-feminist landscape photographs with works made by artists such as Judy Chicago, Carloee Schneeman, and Ana Mendieta among others. For example (see Figure 3), Chicago and Mendieta both photographed their own nude bodies in outdoor scenes, acting as “active agents of renewal and regeneration in nature.”17 In a similar way to Brigman, they reference either vulnerability or strength. Wolfe, in addition to other art historians such as Nancy Kuhl, further elaborates that Brigman’s photographs are a type of performance art which is “antecedent to [...] experimental performance art that emerged in the art world in the 1960s and 70s.”18 Although the idea of ‘feminist art’ did not exist until much after Brigman’s productions, the artist’s own writings reveal that she derived “power from [her] camera,” and sought to express this power in her compositions.19 To impose the label of ‘proto-feminist’ on Brigman as an artist is thus fitting, as it acknowledges that she was conscious of both her femininity as well as her struggles as a woman. In contrast to “prevailing art practices of the time...Brigman’s photographs of women in the landscape seem radical,” as proposed by art historians Olivia Lahs-Gonzales and Lucy Lippard.20 The purpose of Brigman’s photographing of women nude and outside was twofold: one, it challenged the idea that men alone can inhabit the public sphere and, two, that only they can depict unclothed women.21 In breaking out of these conventions, her pieces serve as a “celebration of women’s development and self-assertion.”22 By investigating her work, though, do we actually see Brigman as a feminist?

A visual analysis of Brigman’s photos before 1911 reveals here figures are portrayed as objects within a landscape, rather than subjects against a background. In this positioning, Brigman elevates women beyond representation as sexual beings, using her body as a stand-in for the feminine form writ large. While it may seem counterintuitive to suggest that integrating the human shape into the landscape raises the feminine form’s power, this integration in effect de-emphasizes the body, thereby making it less sexed. Treatment of the bodies as objects rather than subjects is conveyed through the lack of heads within Brigman’s photographs. In contrast to portraiture, the figures in Brigman’s compositions are not meant to be seen as individuals but simply body-like forms. Recalling the similarities drawn between the environment and the figure within the first example in this paper, The Lone Pine (Figure 1), we can now understand how Brigman muted the individual identity. Rather than occupying the focal point of the composition, the figure emulates other elements of the landscape, and thus the subject becomes part of the topography. This trend is continued throughout the figure’s body—her folded leg echoes the triangular shadow created by a niche in the rock at the bottom of the frame, and the curl of the figure’s head into her body elicits a weariness akin to the heaviness of the rocks, grounding the figure to the cliff. Furthermore, depicted emerging from a crevice created by two rock faces, the centrally located figure in The Cleft of the Rock (Figure 4) moves beyond simply mirroring the landscape towards integration into the scenery itself. Brigman accomplishes this integration through both the arrangement and the physical manipulation of the medium. First, the limbs of the figure continue the lines of the rock, emphasizing the interrelation of the body with nature. Further, diagonal stripes mold the body into the terrain, mimicking the geographical striations of the rocks. These stripes were added after the initial exposure by the artist through a manipulation of the emulsion. In this way, “Brigman’s [figures] are of the landscape, not in the landscape.”23

Figure 4

In these earlier photographs, by simply integrating the figure into the landscape, Brigman subverts a typically masculine representation, that of a connection to nature. Art historian Deborah Bright claims that males often photographed landscapes as a way to claim their superiority over it as triumphant victors.25 By inserting feminine figures into the natural scenery, Brigman does not declare victory for these figures over their environment, and, instead, situates them as part of the topography—making them objects rather than subjects. When the audience learns these figures are feminine, we are able to view their integration into the landscape as an excision of erotic dimension, thereby elevating the status of the female nude from the position of an object which is sexualized to simply occupying the position of object.

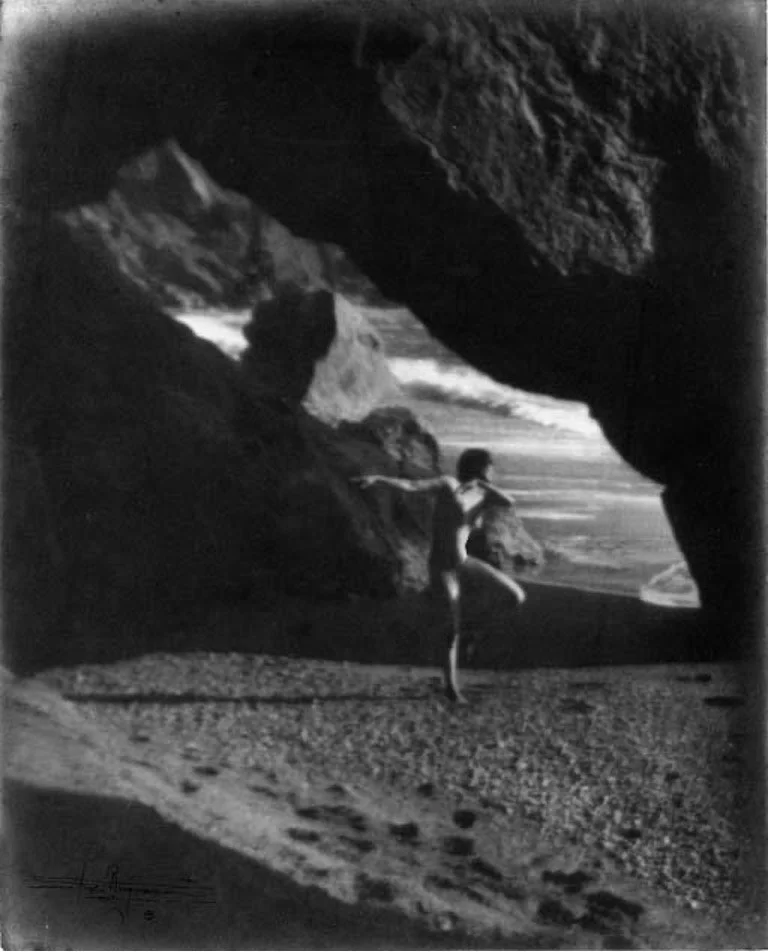

At the same time, however, Brigman’s compositions after 1911 transcend depictions of the feminine body as part of the landscape while also interrelating the two through a representation of emotional struggle. Rather than merely melding their bodies into the environment, Brigman reclaims her figures’ humanity as emblematic of shared human experiences. These later pieces depict a connection to nature which surpasses merely occupying this natural space and instead emphasizes the expression of the figure toward freedom, as seen in the open-bodied motion of the figure in the Ballet de Mer (Figure 5). Ballet De Mer portrays a figure standing on one leg on a beach encompassed by looming rocks and a breaking tide. Pyne asserts that the “circular rhythm of the dancer’s whirling pirouettes [...] ties together the sea and rocks” that surround her, in effect making the figure ‘one with nature’ while simultaneously evoking a sense of grandeur and majesty.26

Figure 5

After 1911, Brigman “retrofitted the narrative cycle of her photographs away from the Sierran nature spirits toward a saga that told of her personal struggle toward freedom of the body and soul.”28 This fact is emulated in a comparison of Ballet de Mer (Fig. 5), made in 1913 with The Lone Pine (Fig. 1), created in 1908. The former depicts a figure in motion—her movement so expressive it consumes her entire body. In addition to the figure’s outstretched arms, which act as a counter balance to her movement, the turn of the figure’s head away from the audience, as well as her bent left leg implies that she is dancing in a circle or a line. Conversely, Fig. 1 portrays a static figure, whose downcast head sinks toward her knees, decidedly grounded to the cliff. Hence, after this time period, Brigman’s photographs reveal feminine figures, whose bodies express emotions and symbolize universal experiences, such as emotional struggle, rather than merely being a part of their surroundings.

However, in all of her compositions, Brigman’s figures are not represented as explicitly female figures, but rather as people who have a shared human identity—elevating them beyond a representation as purely sexed beings. The aforementioned lack of information about the figure’s head emphasizes that these figures personify a generalized humanity more than an individual identity. Additionally, Brigman removes the typical identifiers of sex, such as breasts and genitalia, through the use of soft focus and contrasting lighting. Even with a small highlight of the proper left breast, the figure in Ballet de Mer (Fig. 5) lacks clear indicators of the body’s sex. Instead, the body in motion becomes an expression of pure emotion. The lack of specificity about sex highlights the humanity of the figures and re-enforces the theme of struggle and connection to nature as something universally experienced by all genders. Indeed the ambiguity of these bodies divorces the composition from a specific struggle (for instance women's liberation from the patriarchy) and allows the compositions to speak about struggle writ large. Moving beyond the representation of the ‘feminine’ as sexually available objects (such as Jean Leon Gerome’s Nude (Emma Dupont), Figure 6) or sexually ‘pure,’ yet eroticized beings (like representations of Venuses, for example in Figure 7), Brigman elevates the feminine body toward a depiction of humans who are not defined by their sexuality.

Figure 6

Figure 7

Yet, Brigman’s compositions also represent female figures in the position of objects within an imagined space. Several elements contribute to the creation of a mythical place within these photographs, including the lack of information about a specific place. Stark lighting removes any identifying features of the land, and somewhat tight cropping focuses the eye on the figure and the immediate region surrounding her. There is no sense of the figure within the full space. For instance in Ballet de Mer (Fig. 5), the human form is pictured next to a hint of an ocean, while the rest of the space is left for the viewer to imagine. In The Lone Pine (Fig. 1), which is shot downwards from a place of high elevation, Brigman only suggests a location through the faint outlines of mountains on the right side of the composition. The arrangement also mutes the specificity of a spatial location through a tight frame on the rocks as the foreground. Furthermore, the lack of connection between the figure and the ground in Cleft of the Rock (Fig. 4) emphasizes the artificiality of the depiction, suggesting that the body ought to be understood more as a floating creature rather than a human.

Kathleen Pyne argues that Brigman’s photographs “emerged from the dynamic between a corrupt urban topos and a redemptive wilderness not far away” and created “monsters and goddesses” each with their own mythology and emotions.31 Here, Pyne references the ethereal, almost other-worldy quality of the figures in Brigman’s photos. Brigman does this through detaching her scene from ‘reality’ via pictorialist techniques. Often she removes some of the emulsion left on the surface of the photograph, thereby physically altering the information originally captured by the machine.32 Through Pyne’s argument, we can understand how the imagined realm in Brigman’s photographs is inextricably tied to her own spirituality, which furthers the sense of other worldliness. In particular, Pyne claims that the figure in The Lone Pine (Fig. 1), which bears similarities to the tree, represents “the pine’s nymph-spirit in its rhyming contour,” and thus elevates the body beyond the physical and into the spiritual realm.33 Brigman sought to make an “imagined feminine sexuality” which, as analysis reveals, refers to the mystical place that each figure occupies.34

The creation of an imagined space situates the photographs within the audience’s imagination and thereby dulls the criticality of de-sexualizing the figures. An imagined space is undeniably removed from reality, but the degree to which it is removed depends on how it is represented. Compositions that portray mystical places are not necessarily detached from real life, but through manipulating her photographs, Brigman places them outside the physical world and instead within the viewer’s mind. Depicting figures in an emotional struggle, Brigman’s images appeal to viewers by calling them to meditate on their own emotional and spiritual journeys. Although the image within the physical photograph denotes a particular location, through retouching—literally scratching off the emulsion of the surface—Brigman divorces the images from reality. She encourages the viewer to create an imagined context to match the imagined space in the photograph.

Photography attempts to capture a single moment in time, artificially distilling continual movement into a still shot. In this way, photography as a medium causes the audience to experience time differently than the depicted subjects.35 Recognition of Brigman’s compositions as singular temporal instances allows the images to exist in an ambiguous time. However, time alone is not enough to create a mythical arena within an audience's perception; this requires the addition of a spatial disconnection as well. As these photographs do not exist in space or time, they do not reflect the lived experience of the audience accurately. While Brigman’s work elevates female subjects by mitigating their sexuality, by placing the figures in an imagined space, she similarly relegates their power into the same fiction. Thus, her photographs imply that women’s bodies are only ever de-sexualized within a mystical locus. This is not to say that women can never escape representation as sexual beings outside of an imagined space, but that Brigman’s photographs never depict women in this way.

Brigman’s photography exists on a grayscale. Rhetorically, however, her work neither completely elevates nor suppresses the status of the female nude. In her early work, Brigman placed unclothed feminine figures within a landscape, treating them as objects more than subjects. However, after 1911, she represented the figures as interacting with the environment, acting out their emotional struggle with nature. Throughout her work, she lessens the sexual nature of the bodies, not explicitly depicting them as female. To those aware of the feminine nature of the figures, this de-sexualization elevates the status of the female nude, as it divorces them from the eroticized gaze typical within the Western art canon, the implied audience. However, Brigman’s work also places these desexualized figures into imagined spaces, thereby dulling the power derived from muting an erotic gaze. The creation of a fantastical space removes the bodies from any temporal or spatial location, and thus separates the bodies from Western cultural values. In turn, this cultural detachment emphasizes the emotion of the figures and fosters a connection with the audience on a human level. In doing so, the compositions focus on how the forms express a shared human identity related to struggle and emotion rather than an expression of the femininity of certain bodies. Although her images exist in an imagined realm, Brigman’s art is an example of how to represent the feminine body as nude without overwhelming references to sexuality and eroticism.

Endnotes

1. Anne Brigman, The Lone Pine, 1908. Gelatin Silver Print, The Getty Museum.

2. Anne Brigman lived from 1869 to 1950 and worked in association with the Photo-Secessionists, led by Alfred Steiglitz, and the pictorialism movement. Therese Thau Heyman, Anne Brigman: Pictorial Photographer / Pagan / Member of the Photo-Secession (N.p.: The Oakland Museum, Art Department, 1974), 1.

3. Nancy Kuhl, Intimate Circles: American Women in the Arts (New Haven, Connecticut: Beinecke Rare book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, 2003), 46.

4. Ann Wolfe, “Laid Bare in the Landscape,” in Anne Brigman: A Visionary in Modern Photography, ed. Ann Wolfe (New York: Rizzoli Electra with Nevada Art Museum, 2018), 160.

5. Eugène Delacroix, Liberty Leading the People, 1830. Oil on Canvas, Louvre Museum.

6. Weston Naef, The Collection of Alfred Stieglitz: Fifty Pioneers of Modern Photography (New York: The Viking Press with The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1978), 96.

7. Naef, The Collection of Alfred Stieglitz, 166.

8. Heyman, Anne Brigman, 8.

9. Kathleen Pyne, Modernism and the Feminine Voice: O’Keeffe and the Women of the Stieglitz Circle (California: University of California Press, 2007), 113.

10. Pyne, Modernism and the Feminine Voice, 113.

11. Wolfe, “Laid Bare in the Landscape,” 172.

12. Heyman, Anne Brigman, 6.

13. Heyman, Anne Brigman, 8.

14. Wolfe, “Laid Bare in the Landscape,” 165.

15. Susan Ehrens, “Songs of Herself: Anne Brigman,” in Anne Brigman: A Visionary in Modern Photography, ed. Ann Wolfe (New York: Rizzoli Electra with Nevada Art Museum, 2018), 182.

16. Ana Mendieta, The Tree of Life, 1976. Silver Dye Bleach Print, Museum of Fine Arts.

17. Wolfe, “Laid Bare in the Landscape,” 169.

18. Ibid, 164; Kuhl, Intimate Circles, 33.

19. Wolfe, “Laid Bare in the Landscape,” 156.

20. Olivia Lahs-Gonzales and Lucy Lippard, Defining Eye: Women Photographers of the 20th Century (N.p.: The St. Louis Art Museum, 1997), 122.

21. Lahs-Gonzales and Lippard, Defining Eye, 126.

22. Ibid, 126.

23. Lahs-Gonzales and Lippard, Defining Eye, 126.

24. Anne Brigman, The Cleft in the Rock, 1907. Gelatin Silver Print, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

25. Deborah Bright, “The Machine in the Garden Revisited: American Environmentalism and Photographic Aesthetics,” Art Journal 51, no. 2 (1992): 67.

26. Pyne, Anne Brigman, 110.

27. Anne Brigman, Ballet De Mer, 1913. Platinum Print, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

28. Pyne, Anne Brigman, 7.

29. Jean-Léon Gérôme, Nude (Emma Dupont), ca 1876. Oil on Canvas, Private Collection.

30. Sandro Botticelli, The Birth of Venus, ca 1485. Tempera on Canvas, Uffizi Museum.

31. Pyne, Anne Brigman, 6.

32. Kuhl, Intimate Circles, 33.

33. Pyne, Anne Brigman, 74.

34. Pyne, Modernism and the Feminine Voice, 113.

35. For more on the discontinuity of photography from time, see Geoffrey Batchen, Burning with Desire: The Conception of Photography (Massachusetts: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1997), 184-187.

Bibliography

Batchen, Geoffrey. Burning with Desire: The Conception of Photography. Massachusetts:

Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1997.

Bright, Deborah. "The Machine in the Garden Revisited: American Environmentalism and

Photographic Aesthetics." Art Journal 51, no. 2 (1992): 60-71. Accessed April 2, 2021.

doi:10.2307/777397.

Ehrens, Susan. “Songs of Herself: Anne Brigman.” In Wolfe, Anne Brigman, 180-219.

Heyman, Therese Thau. Anne Brigman: Pictorial Photographer / Pagan / Member of the Photo-

Secession. N.p.: The Oakland Museum, Art Department, 1974.

Kuhl, Nancy. Intimate Circles: American Women in the Arts. New Haven, Connecticut:

Beinecke Rare book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, 2003.

Lahs-Gonzales, Olivia and Lucy Lippard. Defining Eye: Women Photographers of the 20th

Century. N.P.: The St. Louis Art Museum, 1997.

Naef, Weston J. The Collection of Alfred Stieglitz: Fifty Pioneers of Modern Photography. New

York: The Viking Press with The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1978.

Pyne, Kathleen. Anne Brigman: The Photographer of Enchantment. New Haven: Yale

University Press, 2020.

Pyne, Kathleen. Modernism and the Feminine Voice: O’Keeffe and the Women of the Stieglitz

Circle. California: University of California Press, 2007.

Pyne, Kathleen. "Response: On Feminine Phantoms: Mother, Child, and Woman-Child." The Art

Bulletin 88, no. 1 (2006): 44-61. Accessed March 20, 2021.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/25067224.

Wolfe, Ann M. “Laid Bare in the Landscape.” In Wolfem Anne Brigman, 154-179.

Wolfe, Ann M, ed. Anne Brigman: A Visionary in Modern Photography. New York: Rizzoli

Electra with Nevada Art Museum, 2018.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Mary Gerhardinger attends Kenyon College in Gambier, Ohio where she studies physics with a minor in philosophy. Her essay was written in a class about the role of women in the studio throughout art history, focusing on female art makers, models, and patrons.