The Philosophy of Pragmatism in the Politics of Democracy: A Method of Overcoming Dualism?

BY MADHAV SINGH, ASHOKA UNIVERSITY

In his seminal lecture, "The Present Dilemma in Philosophy," William James described the history of philosophy as that of a clash of certain human temperaments.[1] This clash is also reflected in the history of the philosophy of democracy. Attempts at outlining the form of democracy have most prominently taken either of the two definitions: procedural or substantive, minimal or maximal, thin or thick. Those who align themselves with the former positions view democracy as a form of government best captured by the set of electoral and political rules, processes, and institutions that comprise it, such as free and fair elections, regularized transfer of power, universal suffrage, and so on. Those who align themselves with the latter positions instead view democracy as a form of government greater than the set of its comprising electoral processes, expressed in terms of the substantive outcomes it produces in the interest of its governed population, such as liberalism, constitutionalism, socialism, and so forth. People thus find themselves torn over the pursuit of the so-called "correct" expression of democracy and, as a result, this dualism—or the conceptual separation of anything into two opposing or contrasting parts, or the state of being thus split—over the formal disposition of democracy has come to dominate much of what and how we think of democracy in political science and philosophy. But, as we shall later observe, dualisms exist not just over formal differences in democracy; in fact, they are endemic to the very functioning of democracy itself.

Through this article, I submit that democracy is a method of governance but also, more crucially, a way of a conjoint, communicated living that exists in a state of uncertainty: it is wedded to formal and functional dualisms while also striving to overcome them. To that end, I argue for a critical expansion in how we understand democracy (and the democratic life) using the framework of early pragmatism as (1) a conciliatory tool for idle disputes and as (2) a means for linking theory to practice. This paper is structured as follows. The first section, building off a Jamesian mode of analysis, interrogates the formal dualism in the philosophy of democracy represented as the conflict between defining the disposition of democracy in either procedural and objective (clean) terms or substantive and subjective (muddy) terms. I demonstrate how one can overcome this debilitating dichotomy by embracing the pragmatist attitude of looking away from the "first things" of democracy, such as rigid categorizations, and looking towards its "last things"[2] such as practical consequences for problem-solving, creative expression, and associational living. In the second section, however, I complicate this reading of democracy by tracing the functional dualism that persists within the practice of democracy in trying to reconcile associated living amongst disassociated members and groups. As a potential solution from pragmatism’s toolkit itself, I present a multidimensional analysis of the notion of social endosmosis to illustrate how it transcends this functional dualism through its novel conceptualization of conjoint separateness. Finally, I conclude by briefly summarizing the takeaways from my argument and presenting a scope and direction for future research.

Formal Dualism: Beyond “Clean” and “Muddy” Democracy

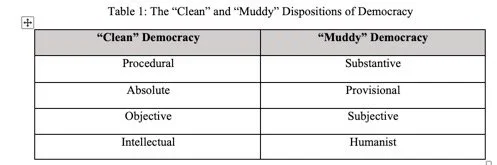

I began by addressing a popular divide in defining democracy as either substantive or procedural, maximal or minimal, thick or thin. But this dispute over the formal characteristics of democracy is only a small (yet significant) part of the larger dichotomy between what I call the “clean” temperament of democracy and the “muddy” temperament of democracy. “Clean” because it emphasizes the institutions and principles of democracy as uncontaminated from how they are normatively experienced by human beings; “muddy” because it emphasizes the constituents of democracy to be thoroughly contaminated with the complexities and particularities of normatively experienced human influences. This method of analysis borrows from James’ “tender-minded versus tough-minded”[3] distinction, but it has been contextualized with salient differences to capture the idiosyncrasies of the democratic temper. [4] Table 1 lists the various discords encapsulated by this dualism:

The “clean” democratic temper subsists most commonly in the minds of patrician professors and finds its abode amongst the ivory towers of many sanitized classroom (or Zoom) discussions. It is procedural, absolute, objective, and intellectual. It is procedural insofar as it regards democracy as self-contained within a fixed system of technical and quantifiable rules and procedures, whether operationalized as the conduct of routine elections, the separation of central powers, or even the equality to vote. It seeks absoluteness in the existence and truth of democracy, which is to say that the principles of democracy can either be present or absent, followed or unfollowed, black or white; there is no possibility of an indeterminate in-between or pesky regions of gray areas. It thus also lays claim to an objective mode of analysis, implying that one can and should evaluate the truth about the measure of democracy in a regime(s) independent of the normativity and biases that underline individual opinions. Finally, it is intellectual because it maintains that the knowledge of democracy can be sustained and advanced only through the use, development, and exercise of the 'thinking' intellect, away from the ‘feeling' emotiveness.

In contrast, the “muddy” democratic temper usually resides in the minds of plebeian activists and social workers navigating the painful 'facts' of everyday experience. It is substantive, provisional, subjective, and humanist. It is substantive because it considers the substance (rather than principles) of democracy as enmeshed in the circumstances, sensibilities, and attitudes of the people—both: the governing and, more importantly, the governed—that constitute it. It exists in a state of provisionality as opposed to absoluteness, given that the existence and truth(s) of democracy are contingent on the particularistic and mutable nature of human claims and demands. It accordingly embraces a subjective frame of analysis, highlighting the role of conscious subjects in influencing, informing, and biasing our knowledge of democratic truths through concrete and normative experiences. Lastly, it is humanist owing to the premium it places on the agency and value of all 'thinking' and 'feeling' human beings.

Now, some of us may not be content with having to choose between the principles offered by the “clean” democratic temper and the experiences offered by the “muddy” democratic temper. We may wish to develop a method that, rather than simply picking from the ‘best’ of the laundry lists on both sides, ingeniously combines the exercise of our powers of intellectual abstraction with some positive connection for actual human lives.[5] A method that ultimately preserves a cordial relationship with facts while also treating aspirational constructions cordially as well. [6]

Fortunately, such a method can and does exist in the form of the philosophy of pragmatism. Pragmatism—very broadly—claims that an ideology or proposition is true if it works satisfactorily and that the meaning of a proposition is to be found in the practical consequences of accepting it.[7] It follows that in order to reconcile the contradictory dispositions of democracy, we must turn towards the understanding of democracy as a practice, as opposed to a position, ideology, or dogma. Here, pragmatism would importantly require the import of three things. First, one must acknowledge and concede that the dualism between the “clean” and the “muddy” character of democracy cannot be settled on purely 'intellectual' grounds, i.e. by appealing to a certain sense of logical, scientific, or metaphysical superiority. And leaving the debate open-ended brings with it the same risk of losing the truth as having to pick between one and discarding the other. Instead, we must resort to understanding democracy through the lens of our "passional nature," as a consequence of the precursive faith in the cooperation of many independent persons.[8] Second, and as philosopher Cheryl Misak points out, "pragmatists are empiricists in that they require beliefs to be linked to experience."[9] As such, a pragmatic explanation of democracy that tackles the nature of its being must be "down-to-earth,"[10] which is to say that the democratic philosophical doctrine must arise out of the human economy of demand and claim-making, intertwined with the natural experience of it. Third, the pragmatic method demands the cultivation of an "attitude of orientation"—or, the attitude of looking away from "first things," such as principles, categories, or supposed necessities, and of looking towards "last things," such as utility, consequences, and facts.[11] This means that we must turn away from the "first things" of democracy, such as electoral or institutional characterizations, and turn towards its "last things," such as "the habits of problem-solving, compassionate imagination, creative expression, and civic self-governance."[12] In short, by integrating these three tenets of pragmatism, one goes from asking—what does the concept of democracy presuppose?—to asking: what does the practice of democracy effectuate?

The answer fittingly comes to us from another influential philosopher of pragmatism, John Dewey. Democracy, as seen through the Deweyan eyepiece, primarily effectuates two things. First, a mode of associated living and conjoint communicated experience.[13] And second, the use of this experiential method—or, “cooperative intelligence”—as a system of inquiry to solve practical problems.[14] But how does the practice of democracy effectuate the aforementioned? Dewey begins by arguing that democracy inspires the custom of expanding a common space for numerous individuals to interact and participate in their shared interests.[15] However, this is not just any common space for every shared interaction—the spatial outlook entails a marked nuance concerning its perpetual adjustment and readjustment in light of its dynamic human subjects. Reflect for a moment on the common space facilitated by democracy for individuals and of their shared interests. It follows that individuals who may wish to participate in a given interest within this common space must refer their own actions and behaviors to that of others who occupy the same domain for reasons of interconnectedness, positionality, and direction. Plus, the more numerous and varied points of contact, the more there is a diversity of stimuli to which an individual has to respond, which, in turn, emphasizes variation in their action.[16] Sure, this may reinforce the sustenance of old mutual interests, but, more importantly, it also promotes the emergence of new ones; and with this widening of the area of shared concerns comes the liberation of a greater diversity of personal capacities and thus the security of freer interactions between social groups.[17] As such, for Dewey, democracy proves useful as a method of inquiry into finding solutions for practical human problems, such as inequality in education or barriers in communication, for its purpose becomes to set free and develop the capacities of human individuals irrespective of their race, sex, class, or economic status.[18] In summary, democracy as a practice fosters a common space of shared interests and mutual participation, which supposedly leads to freer interaction between social groups and the upliftment of all individuals.

Functional Dualism: Deweyan Democracy in an “Undesirable Society”?

I used the modifier "supposedly" for a reason, which I hope will become clear from a more in-depth cause and effect analysis of Deweyan democracy herein. The above-delineated effects of democracy as a mode of associated living, conjoint experience, and social upliftment encounter a contradiction from what we took to be their assumed causes. To reach the conclusions of these effects in my previous exploration, I (like Dewey) conveniently assumed at the outset that democracy at least incites a common space for individuals to participate in some shared interests. But what happens when the very emergence of this common space is obstructed internally and externally through barriers that prevent free social intercourse and the communication of experience? For such a condition is what Dewey anticipated through his characterization of an "undesirable society."[19] The nature of an undesirable society matches in content, if not in name, to the nature of a despotically governed state: "there is no extensive number of common interests; there is no free play back and forth among the members of the social group. Stimulation and response are exceedingly one sided."[20] Suffice it to say that there is a lack of an equal opportunity to receive and take from the interaction of others, which results in the loss of meaningful experience and arrests the ability to secure flexible readjustment of societal institutions.

To account for this functional dualism in the practice of democracy that endeavors for conjointness while existing within the separateness of an undesirable society, I turn towards the concept of social endosmosis. Originally conceptualized by philosopher Henri Bergson, and later by William James, to demonstrate the interaction of the mind with nature, the term was soon appropriated by Dewey as a descriptor for interaction between social groups.[21] However, it comes as a great blow that Dewey only ever employed the expression of social endosmosis once across all his writings, and it remains an undertheorized phenomenon outside a small body of literature. Thankfully, some like B.R. Ambedkar—Indian jurist, social reformer, and a student of Dewey—have managed to not only preserve the interactive content behind social endosmosis but also complicated it through its contextualized, application-oriented usage. Therefore, I submit that a comprehensive understanding of social endosmosis requires serious engagement with its three idiosyncratic dimensions. First, as per the dimension given to it by Dewey, it implies gradation without separation amongst different social groups.[22] This does not mean that differences between social groups based on volume or even dispositions will cease to exist altogether, but that the barriers such as “high” and “low” separating them must be undermined. Second, in its Ambedkarite flavor, the manner in which social endosmosis undermines these barriers is through fluidity—or, by the promotion of numerous channels through which groups and individuals are suffused with the nutrient of each other's creative intelligence.[23] Third, and as noted by Mukherjee, social endosmosis accommodates gradation within fluidity through the idea of the semi-permeable "porous septum,"[24] a membrane that provides for the privacy of individuals without enclosing them within impermeable walls. Taken together, the concept of social endosmosis allows Dewey, Ambedkar, and Mukherjee to reconcile the otherwise antithetical ideas of separateness and conjointness, thus facilitating a distinctly pragmatic way of sustaining the democratic life within an undesirable society. Figure 1 illustrates the multidimensional nature of social endosmosis among groups (G1 to Gn) demarcated by porous septa (S1 to Sn-1).

Figure 1. Social Endosmosis as Conjoint Separateness

Therefore, if democracy is indeed the pragmatic solution to practical human problems, then social endosmosis is what endows viability to that solution by reconceptualizing what barriers mean for the permeability of action. This can be better substantiated once we also identify the consequences of social endosmosis as a "joint activity"[25] through which individuals (1) subsist transactionally with their social environment and (2) cultivate dispositions by the use of things. In our case, the social environment consists of various differentiated groups; the thing to be utilized and experimented with is democracy; and the cultivation of an appropriate democratic disposition will thus take place when individuals contribute to the joint activity of social endosmosis, which will allow them to appropriate the purpose which actuates it (conjointness), become familiar with its methods and subject matters (freer social intercourse), acquire needed skill (communication), and become saturated with its emotional spirit.[26] Furthermore, joint activities like social endosmosis denote power rather than a weakness because they strengthen interdependence and are accompanied by a growth in individual and collective abilities that increase our so-called "social capacity."[27] This social capacity makes possible the fulfillment of tasks that might have been otherwise impossible for an individual to accomplish on their own using the means of a singular physical or mental capacity.

In ultimately tying together the discussion of democracy and social endosmosis, one would be remiss to not respond to what is perhaps the most popular and potent charge against it: the unwillingness of some human agents to associate with others, regardless of the barriers in an undesirable society. Misak frames it best: "[…] these noble sentiments [of democracy and freer intercourse] are again ineffective against those who would argue that they are deeply uninterested in living amongst, or associating with, a minority class, race, or different territorial group and would much prefer to do away with them."[28] There is truth to this, no two ways about it. At first glance, it might seem that Dewey tried to include a failsafe mechanism in his writings to safeguard against this objection using what I call the thesis of resocialization. It posits that all those who partake in, or are exposed, to the experience of communication—whether of knowledge, interests, activities, or aspirations—have their experience of the communication modified in some form.[29] Thus, the joint activities of communication such as social endosmosis are self-sustaining practices once kick-started because they set into motion a cycle of the resocialization of previously socialized attitudes. Granted, the real problem, as Misak pointed out, was the act of kick-starting them within a disinclined audience in the first place.

But where the teacher fell short, the student swooped in. Ambedkar took the thesis of resocialization, combined it with the power of an external influence—such as electoral, political, or constitutional reforms—and ran with it. In his seminal commentary on the oppressive and undemocratic nature of the caste system in India, he echoed part of Misak’s objection by acknowledging how the “anti-social spirit”[30] of the Hindus acted as one of the worst offenders in fostering exclusivity, isolation, and self-interestedness amongst the dominant social group. However, though breaking this deadlock was difficult, Ambedkar realized that a potential solution consisted of mobilizing external influence or actors to kick-start the process of social endosmosis. One such instance of his endeavor to achieve the same is evident in his 1919 witness to the Southborough Committee, which decided upon political reforms for India under the British colonial rule.[31] Ambedkar (2014) emphasized how different social groups in isolation tend to create their own distinctive “like-mindedness,” but when the same groups are brought together in a political union, it can create a new like-mindedness in place of the old, “which is representative of the interests, aims, and aspirations of all the various groups concerned.”[32] But he also believed that the social divisions in India were different from those in Europe or the U.S.A, and thus political reform had to accordingly share a two-way street with social reform and endosmosis if it were to be successful. Additionally, this synthesis of political reform with social reform would go on to become a template for Ambedkar’s activism, as he utilized the same argument in later interventions such as the 1930 Round Table Conference in London, where he justified compensatory discrimination in the form of separate electorates for the untouchables. In short, though Misak’s counter-argument represented an often-overlooked limitation of the associational idea behind democracy, proponents of Dewey, such as Ambedkar, found their own ways of building upon the pragmatic tradition through contextual improvisation.

Conclusion

My purpose in this essay has been to explain and interrogate the import of early American Pragmatism in the politics, philosophy, and practice of democracy. I have not tried to say all that could be said on the subject. There is scope in future studies for either adopting a more exploratory direction and incorporating the view of other philosophers of pragmatism or taking up a more critical stance by considering further counter-arguments and objections to the pragmatic reading of democracy. However, within the ambit of what I did say over the course of this essay, I hope to have accomplished four things. First, to have demonstrated that the formal dualism in the temperament of democracy—whether "clean" or "muddy"—is myopic because it presents itself as having to pick one over the other and is more concerned with the presumptions of democracy than the practice of it. Second, to have outlined a method of reconciling these temperaments of democracy using the philosophy pragmatism and, in particular, through the Deweyan ideas of associated living and cooperative intelligence in democracy. Third, to have introduced the functional dualism of having to sustain the democratic life within an undesirable society that erects barriers between groups and individuals to prevent or minimize communication, and how the concept of social endosmosis attempts to overcome this through its multidimensional nature and consequences as a joint activity. And fourth, to have engaged with a popular challenge to the idea of social endosmosis and democratic living, and its implications for the creative appropriation of the pragmatic tradition.

Endnotes

[1] William James, “Lecture 1: The Present Dilemma in Philosophy,” in Pragmatism: A New Name for Some Old Ways of Thinking, 17th ed. (New York: Longmans, Green, and Co, 1922), pp. 6-7.

[2] William James, “Lecture 2: What Pragmatism Means,” in Pragmatism: A New Name for Some Old Ways of Thinking, 17th ed. (New York: Longmans, Green, and Co, 1922), pp. 53-55.

[3] William James, “Lecture 1: The Present Dilemma in Philosophy,” in Pragmatism: A New Name for Some Old Ways of Thinking, 17th ed. (New York: Longmans, Green, and Co, 1922), pp. 11-13.

[4] This is why I refrain from calling this a “rationalistic versus empiricist” dualism of democracy. In my theorization, the “clean” temper is not synonymous with the rationalistic temper, and the same is true for the “muddy” and the empiricist temper.

[5] William James, “Lecture 1: The Present Dilemma in Philosophy,” in Pragmatism: A New Name for Some Old Ways of Thinking, 17th ed. (New York: Longmans, Green, and Co, 1922), pp. 20.

[6] Ibid., pp. 40-40.

[7] Douglas McDermid, “Pragmatism,” Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2006, https://iep.utm.edu/pragmati/.

[8] William James, “The Will to Believe,” in The Will to Believe: And Other Essays in Popular Philosophy. (New York: Longmans, Green, and Company, 1907), pp. 11; 24-25.

[9] C. J. Misak, “Preface,” in The American Pragmatists. (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2013), pp. x-x.

[10] Ibid.,

[11] William James, “Lecture 2: What Pragmatism Means,” in Pragmatism: A New Name for Some Old Ways of Thinking, 17th ed. (New York: Longmans, Green, and Co, 1922), pp. 53-54.

[12] David Hildebrand, "John Dewey", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2018 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2018/entries/dewey/.

[13] John Dewey, “The Democratic Conception in Education,” in Democracy and Education: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education. (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1922), pp. 101-101.

[14] C. J. Misak, “John Dewey (1859-1952),” in The American Pragmatists. (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2013), pp. 135-135.

[15] John Dewey, “The Democratic Conception in Education,” in Democracy and Education: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education. (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1922), pp. 100-102.

[16] Ibid., pp. 101-101.

[17] Ibid., pp. 114-115.

[18] Ibid., pp. 101-101.

[19] Ibid., pp. 115-115.

[20] Ibid., pp. 97-97.

[21] Arun P. Mukherjee, “B. R. Ambedkar, John Dewey, and the Meaning of Democracy,” New Literary History 40, no. 2. (2009), pp. 352-352.

[22] John Dewey, “The Democratic Conception in Education,” in Democracy and Education: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education. (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1922), pp. 98-98.

[23] B.R. Ambedkar, "Annihilation of Caste,” in Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar's Writings and Speeches, vol. 1, ed. Vasant Moon. (Jhajjar: Dr. Ambedkar Foundation, 2014), pp. 24-24.

[24] Arun P. Mukherjee, “B. R. Ambedkar, John Dewey, and the Meaning of Democracy,” New Literary History 40, no. 2. (2009), pp. 352-352.

[25] John Dewey, “Education as Direction,” in Democracy and Education: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education. (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1922), pp. 34-35.

[26] John Dewey, “Education as a Social Function,” in Democracy and Education: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education. (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1922), pp. 26-26.

[27] John Dewey, “Education as Growth,” in Democracy and Education: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education. (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1922), pp. 51-52.

[28] C. J. Misak, “John Dewey (1859-1952),” in The American Pragmatists. (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2013), pp. 135-135.

[29] John Dewey, “Education as a Necessity of Life,” in Democracy and Education: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education. (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1922), pp. 6-6.

[30] B.R. Ambedkar, "Annihilation of Caste,” in Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar's Writings and Speeches, vol. 1, ed. Vasant Moon. (Jhajjar: Dr. Ambedkar Foundation, 2014), 51-52.

[31] Arun P. Mukherjee, “B. R. Ambedkar, John Dewey, and the Meaning of Democracy,” New Literary History 40, no. 2. (2009), pp. 353-353.

[32] B.R. Ambedkar, "Evidence Before the Southborough Committee on Franchise (1919),” in Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar's Writings and Speeches, vol. 1, ed. Vasant Moon. (Jhajjar: Dr. Ambedkar Foundation, 2014), 248-49.

Bibliography

Ambedkar, B. R. Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar: Writings and Speeches. Jhajjar: Dr Ambedkar Foundation, 2014.

Dewey, John. Democracy and Education: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1922.

Hildebrand, David. (n.d.). John Dewey. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2018 Edition). https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/dewey/.

James, William. The Will to Believe: And Other Essays in Popular Philosophy. New York: Longmans, Green, and Co, 1907.

James, William. Pragmatism: A New Name for Some Old Ways of Thinking. New York: Longmans, Green, and Co, 1922.

McDermid, Douglas. 2006. Pragmatism. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://iep.utm.edu/pragmati/.

Misak, C. J. The American Pragmatists. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Mukherjee, A. P. “B. R. Ambedkar, John Dewey, and the Meaning of Democracy.” New Literary History 40, no. 2 (2009): 345–370

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Madhav Singh is a student at Ashoka University, pursuing a Bachelor of Arts (Hons) in Political Science. His current area of interest includes electoral accountability as a determinant of democratic resilience against populist radical right parties and its variation across varieties of democratic regimes. He has written and published several independent research papers in peer-reviewed journals such as the Michigan Journal of Political Science and the International Journal of Policy Sciences and Law. In the past, he has also worked as a research assistant for several organizations and think tanks, including the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies, Centre de Sciences Humaines, Centre for New Economic Studies, and KPMG Global Services. Apart from academia and research, he is deeply passionate about progressive rock and the French New Wave.