The Dead Walking Behind Us: Queer 'Elegy,' Classical Eros, and Desire as Translation in Oscar Wilde and A.E. Housman

by Kit Pyne-Jaeger, Cornell University

In his 1997 play The Invention of Love, Czech playwright Tom Stoppard includes a scene wherein Oscar Wilde's close friend, the journalist Frank Harris, is seen rowing the River Styx in a murky, classicized underworld with two ahistorical companions: politician Henry Labouchère and Chamberlain, an acquaintance of the fin-de-siècle English poet A.E. Housman. Harris mentions offhandedly his first introduction to Housman's poems:

HARRIS. Robbie Ross gave me this man's poems. He got several off by heart to tell them to Oscar when he went to see him in prison. [...]

CHAMBERLAIN. Housman? I know him!

HARRIS. I think he stayed with the wrong people in Shropshire. I never read such a book for telling you you're better off dead.[1]

This exchange offers an elegant summary of the network of influences, temporalities, and cultural points of reference this paper will apply to the poetics of Wilde and Housman. Robert Baldwin "Robbie" Ross, Wilde's supposed first male lover, did in fact memorize poetry to recite to Wilde during prison visits, including a number of poems from Housman's first and best-known poetry collection, A Shropshire Lad. Though their sexual relationship lasted only a short time, Ross remained wholeheartedly devoted to Wilde, nursing him on his deathbed and defending his literary legacy after his death. Housman, too, nurtured a steadfast devotion to a man inaccessible to him—his heterosexual college friend Moses Jackson—after Jackson's death and until his own. The image is a poignant one: Ross, separated physically from Wilde by the bars of his cell and emotionally by Wilde's love for his "lily of lilies" Alfred Douglas, communicating his affection by reciting the poems of another man whose beloved was both physically and emotionally out of his reach. (When A Shropshire Lad was published in 1896, Jackson was married with children and living in India as the principal of Sind College, Karachi.) Stoppard locates Harris' narration of this moment in a stylized Greco-Roman underworld, contextualizing its evocation of love, longing, absence, and "translation" in a landscape that both Wilde and Housman, gifted Oxonian classicists, would have recognized as appropriate. Using Anne Carson's characterization of classical "eros as lack" in Eros the Bittersweet, this paper will explore the queer resonance of depictions of eros directed at an inaccessible or unresponsive love object in Wilde and Housman's poetics, focusing specifically on the positioning of death as a component of, rather than an obstacle to, eros.

To contextualize both the genre of Victorian elegy as Housman and Wilde would have understood it and the poetic framework available for the erotic lack of eros at the end of the 19th century, it is necessary first to turn to the text that helped to define elegy within its century and was certainly formative to the late Victorian perspective on the literary homoerotic. Alfred, Lord Tennyson wrote his magnum opus, the 732-stanza "In Memoriam A.H.H.," over the course of sixteen years following the untimely death of his beloved friend Arthur Henry Hallam. Though it can be argued that Tennyson's flights into metaphysics and theology render it something other than a simple elegy, "In Memoriam" exemplifies Cavitch's definition of elegy as "a poem about being left behind [...] a genre that enables fantasies about worlds we cannot yet reach."[2] In a passage that is the opposite of metaphysical, Tennyson mourns that, not knowing of Hallam's death, he was "Expecting still his advent home; / And ever met him on his way / With wishes, thinking, 'here to-day,' / Or 'here to-morrow will he come.'"[3] This is a simple expression of the ordinary experience of grief, recalling one's hope and realizing once again that the loved one's "advent home" will never occur again, and that, with "no second friend," the poet is left behind, helpless. He goes on to envision "worlds he cannot yet reach" both in allegorical conceits of fantasy—comparing himself to "a happy lover" discovering his beloved's absence,[4] a widower feeling his wife's "place is empty,"[5] and so forth—and in death itself, the only event that promises the potential of a reunion: "My Arthur, whom I shall not see / Till all my widow'd race be run."[6] Carson, defining eros as a process of triangulation, explains that "as the planes of vision jump, the actual self and the ideal self and the difference between them connect in one triangle momentarily"[7]—the "ideal self" being the imaginary self able to join with and possess the love object, which operates in the mirage-like context of an unreachable, imaginary future.

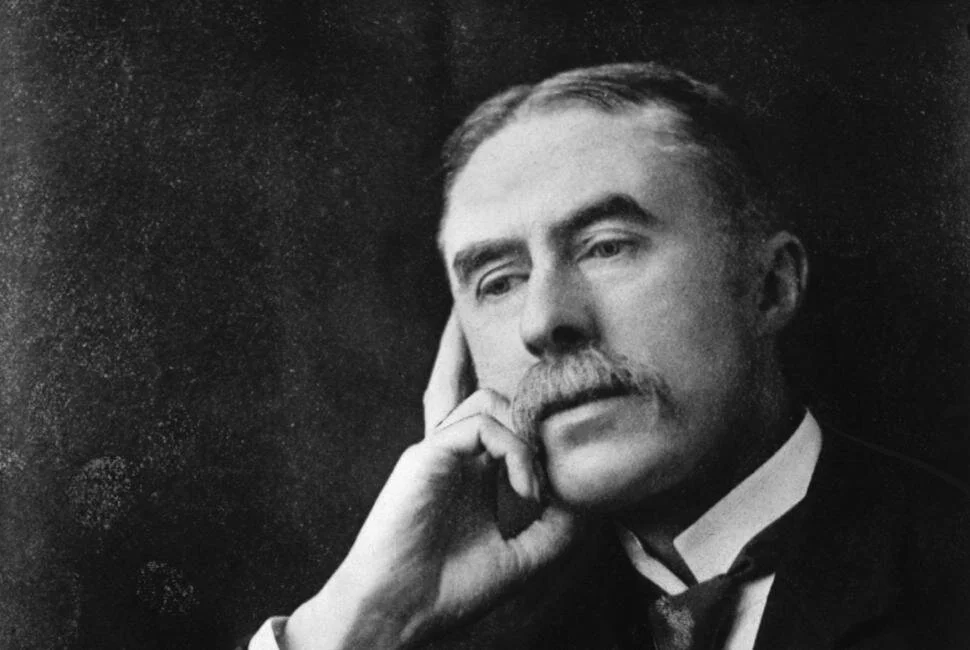

Photo by Hulton-Deutsch from the Hulton-Deutsch Collection via Getty Images from Poetry Foundation

The gulf between those selves, Carson says, is the space where eros is experienced, eroticizing lack not only through the absence of the love object but through the absence of an (under)world where contact with the love object is possible. When Tennyson imagines renewed contact, spiritual or physical, with Hallam, it is in the context of Hallam "from the grave / [Reaching] out dead hands to comfort me,"[8] or of their being welcomed into heaven as a "single soul,"[9] unified both in body and mind. Referring specifically to "In Memoriam," Craft concludes that "the elegiac mode constrains the desire it also enables: the sundering of death instigates an insistent reparational longing, yet it claustrates the object of this desire on the far side of a divide that interdicts touch even as it incites the desire for touching."[10] The death of Hallam functions as the catalyst for the new-found lack of the love object that makes possible the tender longing of "In Memoriam"'s homoerotic eros, and thus death, having produced Tennyson's eros, is also the only possibility for its resolution, the only space where desire can be fulfilled. (The River Styx, as it were, must be crossed.)

However, Craft also argues of "In Memoriam" that "death and not gender is the differential out of which longing is so painfully born; it is death that breaches the perfect male couple and opens it to the circulations of desire."[11] Conversely, I argue that in applying Carson's interpretation of classical eros to "In Memoriam," it becomes clear that both death and gender enable the opening of the gap of eros, firstly because Tennyson's portrayal of his relationship with Hallam relies on conceptions of "love" and "death" mediated specifically by Victorian archetypes of male homosociality, and secondly because Tennyson's rhetoric, scope, intertextuality, tradition—in short, his poem's historicity—are in many ways unique to the experience and education of the Victorian man. Commenting on the poetics of male love in The Invention of Love, Reckford says that "'love of comrades,' as Stoppard suggests, is more than euphemism or late-Victorian sentimentality,"[12] and that "the true lover-friend, the true comrade, will die for his friend, or descend to Hades to (try to) rescue him, or die by his side in battle."[13]

The 'love of comrades' so extolled by Stoppard's Housman is not merely the playwright's invention, nor is it the historical Housman's; it is a trope, perpetuated by Victorian classicists like John Addington Symonds who advocated a doctrine of spiritualized male love, that played a substantial role in the English literary and cultural conception of male homosociality at least until the Second World War.[14] In "In Memoriam," Tennyson declares, "Ah yet, ev'n yet, if this might be, / I, falling on his faithful heart, / Would breathing thro' his lips impart / The life that almost dies in me."[15] This is the quintessential "love of comrades," holy and self-sacrificing, that would be given its purest form in the likes of Wilde's speech propounding "the love that dare not speak its name" during his trial at the Old Bailey and poems like Housman's "Diffugere nives" (a translation of Horace) or "If truth in hearts that perish." "In Memoriam" "[discloses] homosexual desire as indissociable from death,"[16] because, in the developing literary tradition of comrade love, death—death as proof of devotion to one another, death as the instigator of longing and suffering but also the sole opportunity for that suffering to end—defined intimate male friendship and, by extension, queer desire as Wilde and Housman understood it.

Wilde's first and only collection of poems, published in 1881, three years after his graduation from Oxford's Magdalen College, postdated "In Memoriam" by some thirty years, but made extensive use of both its stanzaic structure and its treatment of desire as eroticized lack. Though few of Wilde's poems from this period are explicitly queer, and none to the elaborate and erotic extent of "In Memoriam," there is nonetheless a queer significance to be found in his characteristic treatment of the love object as inaccessible or forbidden. His earliest surviving poem, "Ye Shall Be Gods," written while he was a student at Trinity College Dublin (1871-1874), includes a quatrain already redolent of Tennyson's eros: "But the life of man is a sorrow / And death a relief from pain, / For love only lasts till tomorrow / And life without love is vain."[17] Though this is an aside in a poem about religious tensions between Hellenism and Christianity, in a matter of four lines it evokes Tennyson and presages Housman in identifying love as life's ultimate achievement, the loss of love as the instigator of the pain that produces the poetry of eros, and death—even though it may have been the cause of love's loss—as the only possible resolution to that pain. The first of Wilde's poems that can genuinely be said to eroticize elegy in the manner of Tennyson, however, is not written for a literal lover, but for a literary one: it is "The Grave of Keats," a figure to whom Wilde would return as an idealized "lost love" throughout his verse. He laments the poet's untimely demise as Tennyson does Hallam's sudden loss, with reference to his beauty, his conversion from lover to love object, and his potential as a Christ figure: "Taken from life when life and love were new / The youngest of the martyrs here is lain, / Fair as Sebastian, and as early slain."[18] Fulfilled and mutual love is once again prioritized as the primary purpose of life (the reference is likely to Keats' fiancée Fanny Brawne), but exists only in the past tense or the imaginary future; just as Keats' lackless love was disrupted by his death, the speaker's love can only ever be the classical eros of lack, fulfilled in romantic fantasy, because its object is no longer living. Per Carson, "Who ever desires what is not gone? No one. The Greeks were clear on this. They invented eros to express it."[19] The speaker of "The Grave of Keats" desires him specifically in his goneness, eroticizing his body in its "martyred" state with a telling comparison to the Early Christian martyr Saint Sebastian, who had become a highly recognizable "icon of erotically charged and then specifically homosexual meaning" in Victorian literary and aesthetic culture by about 1850.[20] Though there is no evidence that Keats himself was queer, Wilde's use of Sebastian as imagistic comparison renders Keats a newly queer love object whose beauty stems from his death and whose queerness stems from his absence. (By this I mean not that the dead Keats retroactively becomes queer himself, but that he is invoked in a "queer" role as the object of the classical eros that Tennyson, with "In Memoriam," had already established as a paradigm of male intimacy and homoerotic desire.)

Wilde reaffirms Keats' transposition into this role in apostrophe that associates him simultaneously with queerness, desirability, and loss: "O proudest heart that broke for misery! / O sweetest lips since those of Mitylene!"[21] Keats, once the lover elegizing the "misery" of his loss, is now himself elegized in terms that resemble the list of body parts characteristic of, for instance, the Renaissance blazon, in which the passive love object is described in sensuously physical terms by the poet-lover. Poetry of eros, Wilde seems to suggest, is an intergenerational cycle of queer love and loss in which lover and love object change places fluidly, in a manner reminiscent of the aging of eromenos into erastes in the Platonic paradigm of same-sex love. The reference to "those of Mitylene" emphasizes the historicity of the cycle by bringing Keats, and thus Wilde, into conversation with some of the earliest known classical poets, Sappho and Alcaeus, both of whom lived in Mytilene on Lesbos in the sixth century B.C. and wrote in praise of queer love and sexuality. Sappho was already a lesbian icon of sorts in late Victorian queer culture—lesbian couple Katharine Bradley and Edith Cooper, friends of Wilde's who published under the pseudonym "Michael Field," were known for their translations of her verse—and no less a personage than Cicero had once "complained that [Alcaeus] was extravagant in writing of 'the love of youths.'"[22]

The Keatsian "Charmides" references yet another classical text whose tacit presence lends a queer subtext to a poem ostensibly about heterosexual relationships, though depicted in the same elegiac terms of eros as lack, devoted to an inaccessible or absent lover. Behrendt reminds the reader that "Charmides is the beautiful youth to whom Socrates is attracted in Plato's dialogue entitled 'Charmides, or Temperance,'"[23] and the poem's first line—"He was a Grecian lad"—seems a wry confirmation to the classically educated reader that this Charmides, subtextually if not narratively, is the same as Plato's, a figure in whom one can recognize beauty and queerness. This Charmides' foremost desire is to make love to a statue of the virgin goddess Athena, despite the risk he runs by doing so: "Ready for death with parted lips he stood, / And well content at such a price to see / That calm wide brow, that terrible maidenhood, / The marvel of that pitiless chastity."[24] Carson, treating again the triangular geometry of eros, comments that "the ruse of the triangle is not a trivial mental maneuver. We see in it the radical constitution of desire. For, where eros is lack, its activation calls for three structural components —lover, beloved and that which comes between them."[25] Charmides grasps that death is what will interpose itself between himself and his love object in order to produce eros' eroticized lack and thus the poem's queerness, both in terms of the same-sex intimacy of its elegiac-erotic tradition and in terms of the object of queer desire being historically inaccessible to the Victorian lover.

Appropriately for the conventions of queer eros, then, it does not first seem to be Charmides who is "dead," but Athena, whose stone body is described in terms not unlike those of a corpse ("pale and argent body," "chill and icy breast"[26]). Ultimately, however, the first section of this poem proves to be a subversion of the paradigm of queer eros Wilde enacts elsewhere: after a sojourn in the wilderness (in which he is compared to Herakles' young lover Hylas, Narcissus, and the androgynous Dionysos rather than uncomplicatedly heterosexual figures), Charmides is killed by his love object, who descends from Olympus to exact justice for his crime, thus upending the necessity of eros for a love object who will not or cannot respond. In noting "the problematic characteristics Wilde associates with heterosexual passion [...]," Behrendt characterizes those of "Charmides" as "(1) self-centered sexual desire where the love object is unresponsive, inanimate, or dead [and] (2) sexual activity which prompts violent retribution."[27] I would argue that these do not reflect Wilde's distaste for "heterosexual passion," but rather, allegorically, his anxieties about the threats Late Victorian society posed to the expression of queer desire. Athena represents potential negative outcomes of the unlawful desire that precedes the eroticized separation of eros, in which the love object reverses the paradigm, claims the active role, and punishes the lover for their desire with legal repercussion or even death.

Conversely, in the second section of "Charmides," the body of Charmides (now itself the passive love object) washes up on the shore near Athens, where a dryad in Artemis's service finds him and attempts to make love to him: "one white girl, who / [...] nor thought it sin / To yield her treasure unto one so fair, / And lay beside him, thirsty with love's drouth, / Called him soft names, played with his tangled hair, / And with hot lips made havoc of his mouth / Afraid he might not wake."[28] Here the dryad, too, seeks intimacy and contact with a love object unable to respond to her, but unlike Athena, Charmides is definitively dead and thus fulfills the demand of Tennysonian eros, where the possibility of the love object being revived by the lover's touch must remain only a sorrowful fantasy. Shortly thereafter, the dryad's role as elegiac lover is disrupted by her own death from an arrow wound, a punishment for her having "broken the law" of chastity as a servant of Artemis: "This murderous paramour, this unbidden guest, / Pierced and struck deep [...] / Sobbing her life out with a bitter cry / On the boy's body fell the Dryad maid, / Sobbing for incomplete virginity / And raptures unenjoyed, and pleasures dead."[29] It appears that, like Charmides, the Dryad has been "caught" in her unlawful desire and punished, meaning that she cannot outlive him, as the lover in the paradigm of eros must, to elegize him and aspire to a reunion in death. Even in her dying moments, she enacts the eros-as-lack of the lover, mourning the mutual, fulfilling love that was never accessible to her in much the same terms as the speaker of "The Grave of Keats" mourns Keats' death before his own birth.

Yet in the third and final section of the poem, the paradigm renews itself and achieves the completion, in the fantasy of afterlife, that must otherwise remain mere fantasy for elegists like Tennyson; the two find one another in "melancholy moonless Acheron,"[30] where "nigher ever did their young mouths draw / Until they seemed one perfect rose of flame,"[31] and "once their lips could meet / In that wild throb when all existences / Seemed narrowed to one single ecstasy."[32] Admittedly, this passage is more nakedly sexual than Tennyson's image of himself and Hallam entering the afterlife as a "single soul," but Wilde's description of the unification of two lovers into one mouth, one body, and one existence in their post-death passion nonetheless operates on the same principle—that eros, the desire that hinges on absence, can only be resolved by death as the ultimate experience of absence, moving oneself from reality into a landscape of the poetic unreal.

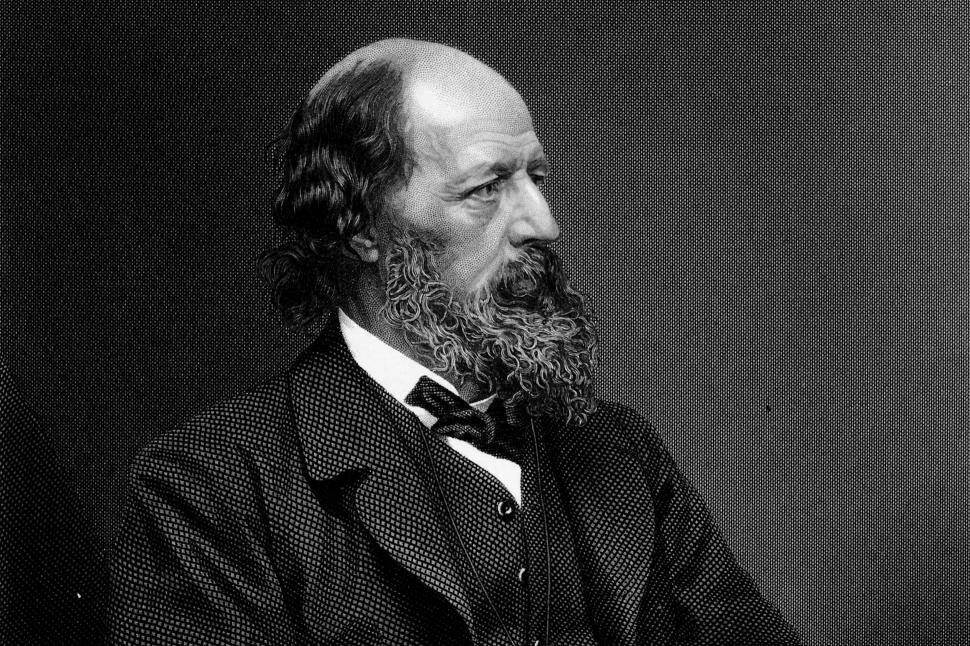

Photo by Time Life Pictures via Getty Images from Poetry Foundation

In another poem of lost love, "Quia Multum Amavi," Wilde makes use of a strikingly Housmanian turn of phrase to refer to a lover who has left him grieving: "Hadst thou liked me less and loved me more [...] I had not now been sorrow's heritor."[33] Coincidence or imitation, more than ten years later, Housman would begin an elegy of unrequited queer desire, XXXI in A Shropshire Lad, with the quatrain "Because I liked you better / Than suits a man to say, / It irked you, and I promised / I'd throw the thought away."[34] This poem, which progresses to the pair bidding one another farewell, the offended love object asking the lover to "forget him,"[35] and, with violent immediacy, the lover dead and informing the love object that, in dying, he has "kept his word,”[36] both subverts and upholds the conventions of queer eros that were previously defined and explored by Tennyson and Wilde. The love object is not dead, but is inaccessible to the lover and resistant to his unlawful desire in a straightforward, historical sense, thus literalizing Wilde's Olympian allegories and keeping the lack essential to eros intact. Though the lover, unusually, does die, that death does not lead his friend to compose an elegy of homoerotic longing, but seems rather to provide a medium by which the lover can demonstrate his own steadfastness and the sacrificial depth of his devotion: he is prepared to die to keep a promise to his friend and the object of his love, a degree of complete commitment to the role of grieving yet constant lover that the reader sees mirrored in Tennyson's sixteen-year effort to memorialize his beloved Hallam.

More conventional in their performance of classical eros are XXXII and XXXVII, poems presenting the speaker as the lover whose queer desire for other men is premised, first, on their having died before him, and, secondly, on his willingness to die for or with them, were it possible. XXXII presents the paradigm within the fantasy of an adolescent boy—"When I would muse in boyhood / The wild green woods among"[37]—emphasizing from the beginning the degree to which any potential for the superseding of eros-as lack to achieve genuine, permanent queer intimacy exists, for Housman as for Tennyson and Wilde, only in an imaginary context. The speaker goes on to describe his idealization of comrade love and elegiac eros as a young person: "It was not foes to conquer, / Nor sweethearts to be kind, / But it was friends to die for / That I would seek and find. / I sought them far and found them, / The sure, the straight, the brave [...] / They sought and found six feet of ground, / And there they died for me."[38] Even in the fantasy of his own play, the speaker is aware that queer desire is a matter of death and loss, and that the best he can hope for as an adult with unlawful homosexual desires is either to express those desires in action, by dying for someone in sacrificial comrade love, or in language, by elegizing those friends who have died for him with a Tennysonian vocabulary of erotic lack. Housman's oeuvre is generally absent even the optimism that Tennyson and Wilde's depictions of queer reunion after death offer, as in XXXVII, a soldier's thoroughly star-crossed experience of queer love: "In blood and smoke and flame I lost my heart. / I lost it to a soldier and a foeman, / A chap that did not kill me, but he tried; / That took the sabre straight and took it striking, / And laughed and kissed his hand to me and died."[39] Here, the lover must settle for a moment of admiration before the death of his love object—which he inflicted himself. This is perhaps the most brutal depiction of eros that has been treated in this paper, in its failure to offer the lover any comfort or amelioration for the lack that catalyzes his desire.

It is impossible, however, to discuss Housman in relation to the question of erotic lack without addressing at more length his poems to and about Moses Jackson, whom he clearly loved deeply from a very young age and continued to love, judging by his poems and references to Jackson in his daybooks, until the end of Jackson's life, if not his own as well. Among his best-known poems, and certainly the best-known that is widely thought to refer to his relationship with Jackson, is VII of Additional Poems, the four-line verse that runs: "He would not stay for me; and who can wonder? / He would not stay for me to stand and gaze. / I shook his hand and tore my heart in sunder / And went with half my life about my ways."[40] What is less often discussed, and what is essential to a reading of this poem in the context of eros, is the fact that this is an almost direct quotation from "In Memoriam," wherein, leaving Hallam's funeral, the poet says to his sister, "Come; let us go; your cheeks are pale; / But half my life I leave behind."[41] Though in Housman's verse the love object has not died, merely departed the speaker's company, the quotation of the phrase "half my life" suggests the profound loss of death and thus the necessity of so acute a loss to the space of longing into which the queer poet of eros writes. Carson says that "if we follow the trajectory of eros we consistently find it tracing out this same route: it moves out from the lover toward the beloved, then ricochets back to the lover himself and the hole in him, unnoticed before. Who is the real subject of most love poems? Not the beloved. It is that hole."[42] In that sense, despite the emphasis this paper has placed on death as a signifier within the context of a theory of erotic lack in Victorian queer poetics, this verse is the best example present of classical eros in Carson's definition: its poignancy and its vividness are both engendered by the image of that sundering, the wound in the lover's body, emotion, and self that the love object's absence has created and that only complete reunion, and communion, with the love object can heal.

Though it falls outside the scope of this paper, a further examination of Carson's theory of classical eros as applied to queer Victorian literary culture might shift its focus from the eros aspect to the classical aspect—that is, discussing the role of historicity and the historicizing process, specifically with reference to classics, in the paradigm of eros as it applies to the queer Victorian consciousness. Poems like Tennyson's, Wilde's and Housman's—by highly educated scholars who had a wealth of knowledge of historical and literary context on which to draw, and an ability to deploy that context with an awareness of exactly the effect a given reference would produce—use a necromantic vocabulary of events, people, and modes of thought already past and dead, communicating erotic lack by translating it into a language made up of absence. Consider, for example, the relationship of Housman's "Epithalamion," "yielding" his "friend and comrade" to a wife, to Sappho 31, in which the speaker can only look on as a man charms the woman she loves, or the literary significance of the Greek adjective γλυκύπικρος, literally "sweetbitter," in the title of Wilde's highly homoerotic and sexually charged "Γλυκύπικρος Ερως." Stoppard's play concerns itself with these men's invention of love, and this paper has concerned itself with the invention of a triangulated paradigm of queer desire in the texts themselves, but what might we find if we turned instead to a triangulation of their selfhood, their writing, and the literary and historical traditions within which they identified themselves? What remains to be said about the translation of queer love?

Notes

[1] Tom Stoppard. The Invention of Love. London: Faber & Faber, 1997, p. 88.

[2] Max Cavitch. American Elegy: The Poetry of Mourning from the Puritans to Whitman. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007, p. 1.

[3] Ibid, p. 7, 21-24.

[4] Ibid, p. 9, 1-8.

[5] Ibid, p. 14, 1-4.

[6] Ibid, p. 10, 17-18.

[7] Anne Carson. Eros the Bittersweet. McLean: Dalkey Archive Press, 1986, p. 62.

[8] Cavitch, p. 81, 15-16.

[9] Ibid, p. 85, 44.

[10] Craft, p. 58.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Kenneth Reckford. "Stoppard's Housman." Arion: A Journal of Humanities and the Classics 9, no. 2 (2001): 128. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20163845.

[13] Reckford, p. 129.

[14] The trope is common in poetry of the First World War, much of which, tonally and prosodically, recalls the classicized homoerotic friendships of the fin-de-siècle; cf. Ivor Gurney's "Servitude" ("only the love of comrades sweetens all"), Siegfried Sassoon's "Absolution" ("what need we more, my comrades and my brothers?"), and "Modernism, Male Intimacy and the Great War," Sarah Cole.

[15] Cavitch, p. 19, 13-16.

[16'] Craft, p. 57.

[17] Oscar Wilde. Complete Works of Oscar Wilde. New York City: HarperCollins, 2003. First published 1908, p. 1, 9-12.

[18] Wilde, p. 1, 3-5.

[19] Carson, p. 11.

[20] Kaye, p. 271.

[21] Wilde, p. 1, 9-10.

[22] Louis Crompton. Homosexuality and Civilization. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2006, p. 28.

[23] Patricia Behrendt. Oscar Wilde: Eros and Aesthetics. New York City: St. Martin's Press, 1991, p. 48.

[24] Wilde, p. 1921.

[25] Carson, p. 16.

[26] Wilde, p. 1922.

[27] Behrendt, p. 50.

[28] Wilde, pp. 1934-1935.

[29] Wilde, p. 1943.

[30] Wilde, p. 1947.

[31] Wilde, p. 1948.

[32] Wilde, p. 1950.

[33] Wilde, p. 2018.

[34] Alfred Edward Housman. A Shropshire Lad and Other Poems: The Collected Poems of A.E. Housman. Edited by Archie Burnett. London: Penguin Classics, 2010, p. 31, 1, 1-4.

[35] Housman, p. 31, 2, 3.

[36] Housman, p. 31, 4. 4.

[37] Housman, p. 32, 1, 1-2.

[38] Housman, p. 32, 1, 5, … p. 32, 2, 8.

[39] Housman, p. 37, 1, 4-2, 4.

[40] Housman, p. 7, 1, 1-4.

[41] Cavitch, p. 58, 5-6.

[42] Carson, p. 30.

Bibliography

Behrendt, Patricia. Oscar Wilde: Eros and Aesthetics. New York City: St. Martin's Press, 1991.

Carson, Anne. Eros the Bittersweet. McLean: Dalkey Archive Press, 1998.

Cavitch, Max. American Elegy: The Poetry of Mourning from the Puritans to Whitman. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007.

Craft, Christopher. Another Kind of Love: Male Homosexual Desire in English Discourse, 1850-1920. Berkeley: U of California P, 1994.

Crompton, Louis. Homosexuality and Civilization. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2006.

Housman, Alfred Edward. A Shropshire Lad and Other Poems: The Collected Poems of A.E. Housman. Edited by Archie Burnett. London: Penguin Classics, 2010.

Kaye, Richard. "'Determined Raptures': St. Sebastian and the Victorian Discourse of Decadence." Victorian Literature and Culture 27, no. 1 (1999): 269-303. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25058450.

Reckford, Kenneth. "Stoppard's Housman." Arion: A Journal of Humanities and the Classics 9, no. 2 (2001): 108-149. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20163845.

Stoppard, Tom. The Invention of Love. London: Faber & Faber, 1997.

--. "The lad that loves you true." The Guardian (London, UK), June 3, 2006. https://www.theguardian.com/books/review/story/0,,1788971,00.html.

Tennyson, Alfred Lord. "In Memoriam A.H.H. OBIIT MDCCCXXXIII." Poems. New York City: Macmillan, 1908. Representative Poetry Online, University of Toronto Libraries. https://rpo.library.utoronto.ca/poems/memoriam-h-h-obiit-mdcccxxxiii-all-133-poems.

Wilde, Oscar. Complete Works of Oscar Wilde. New York City: HarperCollins, 2003. First published 1908.

About the Author

Kit Pyne-Jaeger is a senior at Cornell University, majoring in Victorian Studies, Classics and English Literature in the College Scholar Program and graduating in Fall 2020. They have been awarded the Corson-Browning Poetry Prize and the George Harmon Coxe Fiction and Poetry Awards from the English Department as well as the 2020 Harry Caplan Travel Fellowship from the Classics Department. Their work has previously appeared in The Haley Classical Journal.