Stones that Speak

By Aldona Casey, College of the Holy Cross

Water Dropper: Poet Li Bai Sleeping Near Pine, Plum and Bamboo, 18th Century

Accession Number: 1938.60[1].

Made in the 18th century, Water Dropper: Poet Li Bai Sleeping Near Pine, Plum and Bamboo is a small fluorite sculpture with a cavity and opening so it could be used as a water dropper in ink making. The piece reinforces the well-known fact that calligraphy and ink were vital to Chinese culture and were considered one of the highest forms of art. This piece shows a sensitivity to material and color that is indicative of a culture deeply in tune with the natural world, Daoist principles, and its ancient past. The attention to detail, ingenuity, and beauty highlight Chinese craftsmanship, but what is really conveyed is the spirit of the stone; a life within the rock that Chinese sculptors were listening to and reveling in. Colored, semi-precious stones have a level of sentience and spirituality within them, similar to that of the taotie, the symbolic forces of Nature, and they were treated as such.

Water Dropper: Poet Li Bai Sleeping Near Pine, Plum and Bamboo is a sculpture made of multicolored fluorite that depicts a man lounging on a large wine jug. The wine jug is cleverly positioned, so that the ink is like the wine being poured out, a witty nod to Li Bai (who was a fan of the drink). This draws a connection between the wine, and the real ink, perhaps both were essential to the creative process! The man, Daoist poet Li Bai, takes up most of the composition and is positioned slightly to the left. Behind the man rises a small background that contains a pine tree which is located just above his head, plum blossoms grazing his torso, and bamboo shoots sprouting at his feet. Overall, the piece is quite intricate for its small size, only standing at about 3 1/4 inches tall and 4 1/4 inches wide. That being said, there are some areas that look slightly unpolished, like the sleeves of the robe and the plum blossoms. In contrast, other areas shine with delicacy, like the lustrous pitcher and the polished facial features which present a smooth stone texture. The artist carved this sculpture using one chunk of fluorite that was naturally variegated, having areas that are colored white, a pink toned purple, and a light blue. There are also beige and off-white striations, which can be seen on the robe, and thin veins that are dark in some areas and light in other areas. Despite being naturally occurring, the color of the fluorite is very striking especially because of the bright purple/pink, paired with the baby blue and milky whites. The colors make the piece look almost artificial. The artist took great care in utilizing the naturally occurring color, delineating the figure with the mauve fluorite, and contrasting this with a blue and white jug, mauve pine tree, and blue foliage. The jug has translucent white swirling designs on it, which mirror an organic form, like seafoam or a cloud. The man has been stylistically flattened as well; made more two-dimensional than life. The face is rounded, and his facial features, like the nose and lips, do not protrude as much as they would in a more realistic rendering. Despite the varying colors, this is all the same rock, and the unification of the material creates a harmonious piece.

In the Chinese tradition of hardstone carving, the material was never a passive participant, but rather was an active, even demanding, force that had a clear voice. Semi-precious hard stones come in a striking range of color and have the possibility to be multicolored. Often this variegation can only be discovered after it is carved into and can prove to be a large challenge or nuisance for an artist with a specific vision. However, Chinese artists anticipated, and embraced, the spontaneity of the material, and welcomed “mistakes” within the stone. These artists allowed the stone to guide their creations,“The Chinese carver... seems as a general rule to have kept foremost in his mind the piece of material he intended to carve...did he...encounter variations invisible at its outset, he might modify even radically his original design.”[1] In a way, it was not the artist manipulating the stone, it was truly the stone guiding the artist. This reflects a broader reverence and understanding of Nature and even connects back to the Daoist principles of flow and wu wei, which is known as effortless action, a noble portion of Daoism. These artists, however, were not completely passive and submissive, but instead worked with the hardstone’s “imperfections” to “turn a potential flaw into a desirable highlight.”[2] The dynamic between the stone and the carver works as a collaboration, rather than the artist controlling or exploiting the material. This relationship goes beyond respect, and more accurately reflects the spirit of man and stone cooperating to create something beautiful. In Peanuts and jujube dates (pictured below), an 18th century Chinese sculpture, the potential of the stone's natural features is fully realized to create an exquisite, almost hyper-realistic, still life. The dates were depicted using the deep, translucent, naturally occurring brown of the stone which mimics the soft wet texture of the dates. The peanuts stand out in contrast, with their matte, rough texture, and life-like beige color.

Peanuts and jujube dates, 18th Century[3].

This stone was quite literally perfect for the subject matter, as if during its formation it was destined to depict dates and peanuts, and it was the artist who revealed its potential. Applying this idea of deliberateness and sensitivity to Water Dropper, new meanings form within the piece. The mauve color works to connect all the mauve elements, in this case the coloration connects Li Bai and the pine tree. Pine trees, one of the “three friends of winter” do not die in winter and are a symbol of self-discipline, steadfastness, and endurance[4]. By using the variegated stone, the artist was able to color correlate the pine trees and Li Bai, meaning to draw comparisons between their strong, enduring natures, or perhaps the commissioner of this piece wanted to transfer these characteristics over to himself. Moreover, the essence of the stone was not lost in the carving. Its rare coloration instantly grabs the attention of the viewer, far before the trees or figure.

Variegated hardstone sculpture exudes individuality and highlights the spectacular wonders of Nature. Though jade can come with some variation, overall it is a uniform, green material. In contrast, hardstone supersedes jade in its variety of color combinations: “While nephrite jade is generally uniform in color with little variation, many hardstones, such as agate, chalcedony, rock crystal, and lapis lazuli, are variegated.[5]”

Water dropper in the shape of a crane

18th Century[6]

Vase with bird and flowers

Qing Dynasty[7]

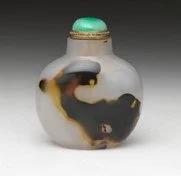

Snuff bottle

18th–early 19th Century[8]

Pictured above are three pieces from the Metropolitan Museum of Art which shows the versatility of these stones, not in simple color either, but translucency, finish, pattern, opacity, and variegation. Water dropper in the shape of a crane and Vase with bird and flowers have a subtle ombre variegation, whereas Snuff Bottle has an abrupt, bold swirl of deep brown against a white background, which is more similar to Water Dropper. A reclining figure is not necessarily a revolutionary subject matter, but the type of stone it was created out of gives the piece a sense of personality and individuality. Unable to be replicated, its uniqueness transcends individuality:

Almost any bronze, however fine...or painting, however delicately executed, can, if an adequate craftsman be available for the purpose, be imitated so closely that only an expert sensitive to the infinitesimal differences...can distinguish one from the other. In the Chinese carvings in partially colored hardstones, however, Nature also has had a hand, and often the craftsman has but followed, sometimes with incredible perspicacity, her directing finger and for a stone whose colors are irregularly disposed, there is small chance that a precise duplicate can be found.[9]

It is not just about the stone, but Nature itself, because it was formed by Nature. Thus, the stone has an active presence, a voice, and holds within it the spirit of Nature, which guides the artist.

Within hardstone carving, the stone collaborates with the artist, exhibiting a level of spirit, sentience even, that lives within the stone, especially rare and colored ones. In an article on Southeast Asian beliefs, it was reported that “Among the Kelabit, as well as among other peoples in Sarawak...people collect and keep small stones that are oddly shaped or coloured...such stones may, it is believed, be inhabited by spirits[10].” Notice the importance placed on shape and color in relation to spiritual potential, and the latter most certainly applies to the Water Dropper.

Scholar's Rock, 18th Century [11]

A belief widely held in “mainland Chinese culture” was that stones were considered to have a “vital life force” within them, which could be tapped into[12]. The notion of a life force especially in such abiotic, “dead” material shows a supreme sense of unity with, and for respect with Nature. Pictured above is a scholar's rock, dated from the same time as the Water Dropper. Though the stone itself was not manipulated, it was elevated to “art” by this stone, despite its different coloration, shape, and purpose, is similar to the water dropper through spirit and materiality. Scholar rocks were believed to symbolize earth, even the cosmos, and could have been used for meditation purposes, or for inspiration to scholars. The idea that rocks held within them more than rock would also explain why artisans treated rare and colored stones with “a sympathy [for] the substances they manipulated.[13]” The Art Institute of Chicago went a step further claiming that Chinese culture held the belief that “The purest essence of the energy of the heaven-earth world coalesces into rock.[14]” Thus the subject matter of Water Dropper: Poet Li Bai Sleeping Near Pine, Plum and Bamboo fades into the background, and rather than being a sculpture on stone, it becomes a stone with sculpture. The variegation suggests individuality, the colors are inviting and vibrant, and the red-brown striations give the piece an ancient, earthy feel. This understanding completely changes the possibilities of how this piece was used. Instead of the sculpture being a decorative piece in a calligraphy set, we could theorize that the spirit, energy, and life force of the rock was meant to inspire creativity everytime the owner used it, or, perhaps, was meant to grant a steady hand, rouse a pleasant demeanor, or grant determination.

The power of stone collecting, which warrants taking note of, has an appeal that moves on from aesthetic and into the spiritual realm while revealing the importance of color. The viewer is presented with the final art piece, the polished vision, yet before it became Poet Li Bai Sleeping Near Pine, Plum and Bamboo, the material was a chunk of raw material. Hardstones and jade were “excavated from mountains and picked up in riverbeds.[15]” The time this sculpture was made, the 1700s, is not ancient, yet many advancements in mining technology had not been made, so this piece was either found or man-mined[16]. A story that epitomizes the influence of stone is about Mi Fu, an eccentric artist and Chinese governor during the Song Dynasty[17]. Mi Fu became so absorbed in stone collecting that he neglected his duties as governor of Lienshuei. Subsequently, he was criticized by his superior, at which point Fu began producing stones from his robe, saying “How can one help loving it?[18]” The debacle became vehement when Fu showed his superior a stone “the color of the sky,” at which point his superior grabbed the blue rock from him, exclaiming “I love it too” as Fu desperately tried to get “his treasure back.[19]” It was only after a beautiful blue stone was shown that Fu’s superior understood the beauty of stone. However satirized, Fu was a real man who loved collecting unique stones and dedicated his life to art. It is a completely viable, and likely, claim that the owner of this water dropper had a similar love, if not respect, for this piece.

The natural beauty of semi-precious harstone combined with Chinese craftsmanship, patience, and creativity make for beautifully thoughtful, at times playful works of art. But the practice of stone carving and collecting reveals a belief that energy, perhaps even spirit or sentience, is held within stones, especially those of unique color or improbable form. Thus Water Dropper: Poet Li Bai Sleeping Near Pine, Plum and Bamboo becomes elevated from an extravagant yet useful calligraphy tool, to a treasured object, manifesting both a connection to a revered poet as well as its own life force.

Endnotes

[1] W. L. Hildburgh. 1942. “Chinese Utilizations of Parti-Coloured Hardstones.” The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 81 (473): 189. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsjsr&AN=edsjsr.868670&site=eds-live&scope=site

[2] Sun, Jason. “Chinese Hardstone Carvings.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/hard/hd_hard.htm (June 2016)

[3] https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/44155

[4] http://artmuseum.princeton.edu/object-package/three-friends-pine-bamboo-and-plum/43777

[5] Sun, Jason. “Chinese Hardstone Carvings.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/hard/hd_hard.htm (June 2016)

[6]https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/hard/hd_hard.htm#:~:text=By%20traditional%20Chinese%20definition%2C%20hardstones,precious%20and%20semi-precious%20stones.&text=Hardstone%20carving%20is%20one%20of%20the%20oldest%20arts%20in%20China.

[7] Ibid

[8] Ibid

[9] W. L. Hildburgh. 1942. “Chinese Utilizations of Parti-Colored Hardstones.” The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 81 (473): 190. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsjsr&AN=edsjsr.868670&site=eds-live&scope=site

[10] Janowski, Monica. “Stones Alive!: An Exploration of the Relationship between Humans and Stone in Southeast Asia.” Bijdragen Tot de Taal-, Land- En Volkenkunde 176, no. 1 (2020): 114.

[11] probably 18th century. Scholar's Rock, front. sculpture. Place: Harvard Art Museums, Department of Asia, https://hvrd.art/o/201687.

[12] Janowski, Monica. 116.

[13] W. L. Hildburgh. 186.

[14] Spirit Stones of China: The Ian and Susan Wilson Collection of Chinese Stones, Paintings, and Related Scholars' Objects. Edited by Stephen Little. Chicago: The Art Institute of Chicago in association with University of California Press, 1999. Pp. 112.

[15]Cartwright, Mark. "Jade in Ancient China." World History Encyclopedia. Last modified June 29, 2017. https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1088/jade-in-ancient-china/.

[16]https://www.generalkinematics.com/blog/a-brief-history-of-mining-and-the-advancement-of-mining-technology/

[17] Beurdeley, Michel. 1966. The Chinese Collector through the Centuries, from the Han to the 20th Century [Translated by Diana Imber]. C. E. Tuttle Co. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cat06787a&AN=chc.b1238892&site=eds-live&scope=site.

[18] Beurdeley, Michel. 1966. The Chinese Collector through the Centuries, from the Han to the 20th Century [Translated by Diana Imber]. C. E. Tuttle Co. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cat06787a&AN=chc.b1238892&site=eds-live&scope=site.

[19] Ibid