Simone de Beauvoir and the Other Woman

By Hui Wong, The University of British Columbia

Simone de Beauvoir in The Second Sex asks: “What is a woman?”[1] Equally, however, the question might be: Who is de Beauvoir’s “woman”? For de Beauvoir, woman, the titular “second sex,” is “second” to man insofar as she is understood in relation to man, is dependent on man, and serves man. In de Beauvoir’s words, “woman represents only the negative, defined by limiting criteria, without reciprocity [from man].”[2] Being “only the negative” is understood in relation to man as the positive. “Man” stands for the positive and the neutral, the gender through which human beings in general are understood and is thus the universal subject to woman as the “Other.” It is “Man” who stands for mankind. While de Beauvoir’s analysis is a useful framework and method for providing accounts of marginalized oppression, her categories of subject and Other are mired with ambiguous boundaries that are ultimately untenable as universal, discrete categories. This limitation in the theory becomes clear when the distinction is reconsidered in light of racialized others who challenge the purported universality of de Beauvoir’s formulation. This paper argues that given these challenges, de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex is most useful insofar as it is a method for accounting for experiences of otherness. Black women are gendered differently from the Black man and racialized differently from the White woman through race, occupying an ambiguous position.

This paper first briefly elucidates how de Beauvoir comes to regard woman as the Other by placing emphasis on Woman as a historically separate category that implies a distinct and totalizing struggle from that of race, class, etc. In relation to (or juxtaposed against) “race,” this account is problematic. As Amey Adkins suggests, Frantz Fanon’s analysis of Black otherness in Black Skin, White Masks “reveals a pattern of analysis uncannily similar to de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex.”[3] Given this similarity, might it not be too much to suggest that de Beauvoir already implicitly relies on racial categories for her notion of the Other? Otherness is a category whose qualities shift depending on their proximity to a European male subject. Finally, this paper offers a revised conception of woman as the Other, proposing that de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex be taken up as a methodology for providing an account of otherness, rather than a concrete and totalizing category.

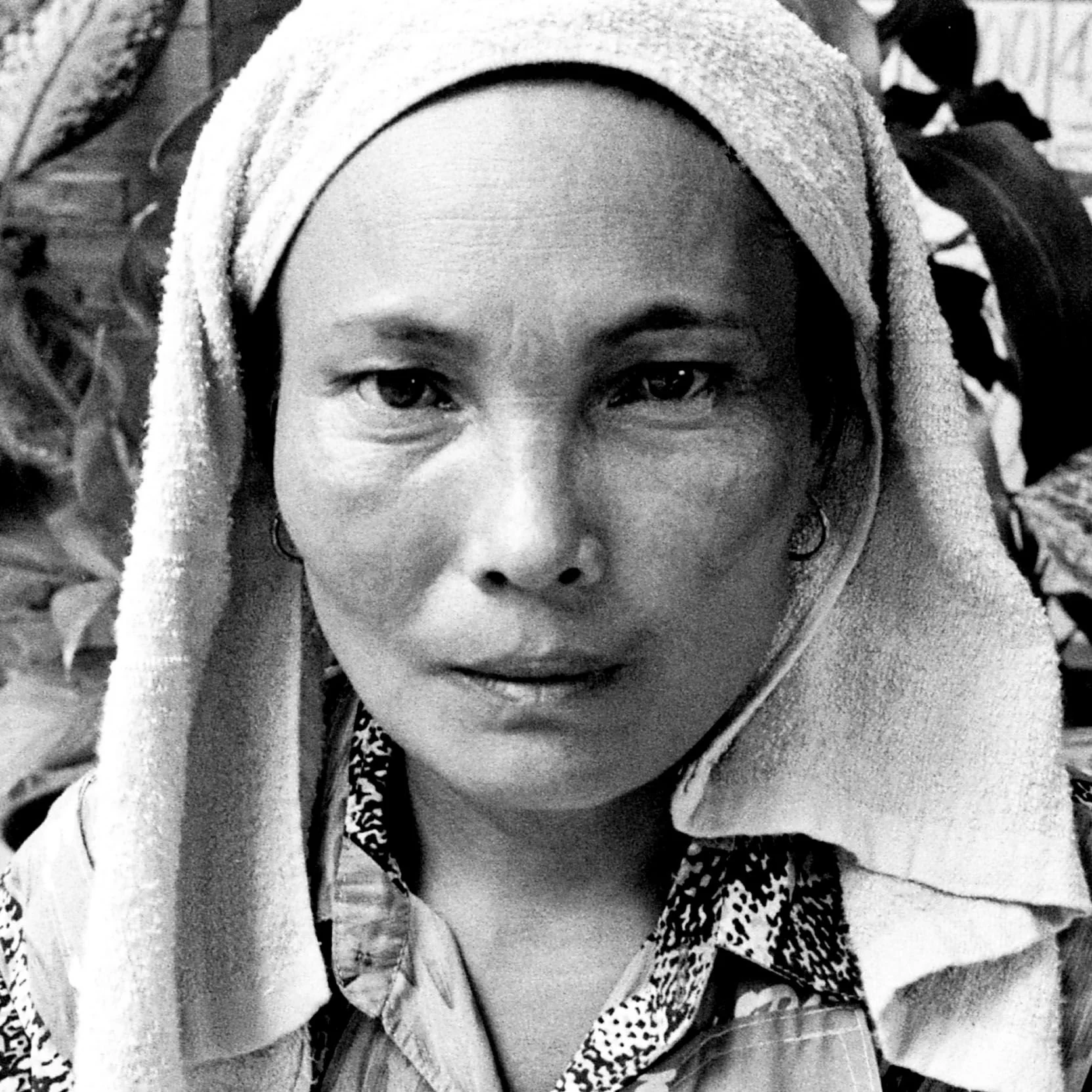

"AWoman-Bangkok,cityifangels"bySailing'Footprints:RealtoReel'(Ronnashore)is markedwithCCBY-NC-ND2.0.

At the beginning of The Second Sex, de Beauvoir, asks: “What is a woman?”[4] For de Beauvoir, the significance of this question largely lies in her asking it—“[a] man would never set out to write a book on the peculiar situation of the human male.”[5] “Situation” is regarded as the facticity of one’s material conditions that constrain existential freedom. De Beauvoir suggests that the situation of the human male has historically been regarded as the universal situation; therefore, a man would never question his “peculiar situation” because his situation has never been peculiar. A woman, on the other hand, “finds herself living in a world where men compel her to assume the status of the Other.”[6] Woman’s situation is dictated by male subjectivity, which has pervaded institutions to systemically regard woman as the Other, naturalizing an inability for woman to transcend her situation. Two questions then arise: how did these categories emerge, and how are they maintained?

First, de Beauvoir suggests that the “division of the sexes is a biological fact,” a “primordial” relationship.[7] For de Beauvoir, it is because the divide between man and woman is biological that its development is unlike those deriving from class or racial lines. The chief difference is that other oppressed groups “have often been originally independent […] [b]ut a historical event has resulted in the subjugation of the weaker by the stronger”; de Beauvoir points to “[t]he scattering of the Jews, the introduction of slavery into America” to demarcate the unique category of woman as the Other.[8] In the first instance, woman are different from racial and religious groups in that other groups have existed as their own collective without reliance on those who later became their oppressors. Further, de Beauvoir notes that although the proletarian class is similar to women in that “neither ever formed a minority or a separate collective unit of mankind,” they are still different because “proletarians have not always existed, whereas there have always been women” as a biological, indeed, an ontological truth.[9] Crucially, this leads de Beauvoir to conclude that because women have always existed in relation to men and have been unable to form themselves into a collective separate from their oppressor, they are destined to be unable to resist men’s oppression as other groups are able. But another part of woman’s Otherness and her lack of resistance hinges on her own complicity, which relates to how the status of the Other is maintained.

A key component of woman’s inability to resist stems from patriarchal institutions that naturalize oppression, systems that “that some [women] find to their advantage because of ‘economic interests and social condition’.”[10] Because some women supposedly find advantages in being the Other, men declare that “she has desired the destiny they have imposed on her.”[11] For de Beauvoir, then, woman is consequently in a double bind; women are limited by their situation and have been naturalized into believing that they desire it. One can also conclude that woman is her situation, that she is woman insofar as she participates in her oppression. Judith Butler reads de Beauvoir’s “view of gender as an incessant project, a daily act of reconstitution and interpretation.”[12] De Beauvoir identifies such roles as “housekeeping and maternity” to be falsely desirable, burdens with “poetic veils” that keep women in her position as Other.[13] These roles have been imposed on women through “oppressive systems” with “complicated material origins.”[14] As such, woman as the Other is formed through a history in which women have never been a collective, always existing in relation to man. In the passage of history, woman’s oppression has been naturalized and women are subject to a system that tempts them into desiring their own gendered oppression, which is constituted and reproduced through their participation in everyday acts.

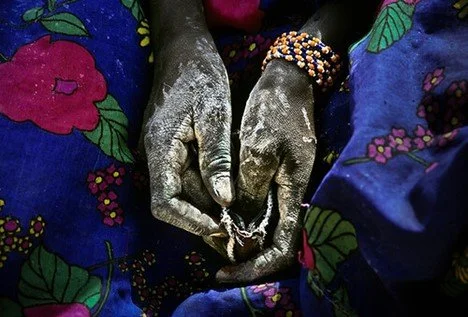

"Creole Choir of Cuba" by Stuart Madeley is marked with CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Does de Beauvoir’s formulation speak to the condition of all women? The Second Sex reads as if it is universal: Woman as the Other is a categorization starting from a “primordial” beginning, and her final call for liberation asks to “abolish the slavery of half of humanity.”[15] I argue, however, that this category is ambiguous, and that de Beauvoir implicitly assumes a specific kind of woman in her formulation of the Other, revealed through de Beauvoir’s own positioning of woman with reference to other marginalized groups. De Beauvoir writes that “there are deep similarities between the situation of woman and that of the Negro,”[16] and that there is no biological precedence for innate characteristics “such as those ascribed to woman, the Jew, or the Negro” (emphasis added).[17] She implicitly characterizes race as a separate category from gender; the critical “or” that hangs between each group distinguishes them. Consequently, the subject is not simply the “Man” who has subjugated these other groups, but “White Man.” By recognizing Black people and women as two discrete categories, a distinct problem emerges: what of racialized women?

The “or” that distinguishes categories reveals either that de Beauvoir’s woman is the Other as a White woman or that racialized women experience their otherness sometimes as a woman, sometimes as a racialized body—depending on her situation. This is as dubious as it sound—such intersectional feminist scholars as Kimberlé Crenshaw have argued that Black women can “experience discrimination as Black women—not the sum of race and sex discrimination, but [distinctly] as Black women.”[18] Thus, de Beauvoir’s categories are revealed to be appealing to a particular universality of Whiteness: the universal man who stands as the subject is revealed to be White; the woman as the Other who can be differentiated from the struggles of racialized others is revealed to be a White woman. While de Beauvoir’s categories, now shown to have racial implications in their subjects, have consequences for the categorization of woman as the Other, the upshot is that it also reveals the universal subject who others as a White man. However, it is unnecessary to look to Crenshaw or later intersectional feminist scholars to arrive at these conclusions; de Beauvoir’s contemporary Frantz Fanon, who locates Black men as the Other, helps to provide an understanding of the intertwined notions of otherness in race and gender, showing that de Beauvoir’s analysis is better taken up as a methodology for providing an account of varying experiences of otherness than a definitive categorization.

In an in-depth comparison of Black Skin, White Masks and The Second Sex, Amey Adkins places de Beauvoir and Fanon in dialogue with each other. Adkins provides key insight into a critical moment, showing how the two thinkers influenced each other, and how French existentialist tradition left its mark on influential postcolonial and gender studies discourse. The crucial similarity is that the two existentialists find their freedom repressed by their situation: “Beauvoir realizes this situation for women who are split in their subjectivities by the image of woman. But […] we see that Fanon recognizes this same structure via the modality of race.”[19] In The Second Sex, women are “split in their subjectivities” because of a patriarchal hegemony that suppresses their subjectivity, over-determining their personhood. For Fanon, a similar suppression arises from the color of his skin: he suggests that “[t]here are times when the black man is locked into his body,”[20] which echoes de Beauvoir when she writes that man “regards the body of woman as a hindrance, a prison.”[21] Indeed, one may notice similarities rather than differences in de Beauvoir and Fanon’s accounts of the otherness of Black (men) and (White) women.

Yet similarities in de Beauvoir and Fanon’s texts do not completely elide their differences. Rather, the thinkers reveal that the crux of their similarity relies on an alterity in relation to the White man. Fanon reinforces the proposition that the universal subject has a race, de Beauvoir that s/he has a gender. But these similarities can only carry a critique of de Beauvoir’s account of woman as the Other so far. To suggest that de Beauvoir’s category does not work because it is exactly like all other “others” simply shifts categorization from a hegemonic woman Other to a hegemonic non-White non-male Other. It may be generative to seek differences between Fanon and de Beauvoir’s accounts, question what each category leaves out in their analyses, and thus attempt to rewrite de Beauvoir’s notion of women as the Other.

Fanon’s account of the relationship between White and Black men challenges de Beauvoir’s notion that race and gender are distinct due to historical precedence. In Black Skin, White Masks, Fanon appropriates Hegel’s master-slave dialectic to suggest that “[o]ne day the White Master, without conflict, recognized the Negro slave.”[22] Fanon’s account of the Black slave’s continuing oppression does not correspond to what, for de Beauvoir, seems to be a key point of difference between the oppression of Black slaves and women—that Black slaves “have often been originally independent […] [b]ut a historical event has resulted in the subjugation of the weaker by the stronger.”[23] For Fanon, this historical imagination of Black people as a collective is meaningless in the praxis of liberation: “the Negro knows nothing of the cost of freedom, for he has not fought for it.”[24] De Beauvoir, in The Second Sex, speaks of women’s passivity as such: “woman may fail to lay claim to the status of subject because she lacks definite resources, because she feels the necessary bond that ties her to man regardless of reciprocity.”[25] Thus, comparative similarity reveals difference; both Fanon and de Beauvoir view their otherness as passive, and de Beauvoir’s appeal to the historical collective independence of Black people as a key point of difference does not seem to hold. De Beauvoir suggests that Black people rely on remembering their individuality to seek liberation, but Fanon replies that the memory has since faded. The similarity, however, also marks that both writers pursued a similar method for an account of their specific otherness to the White man.

Reading de Beauvoir and Fanon dialectically allows for challenges to discrete categories of otherness while retaining their approach as a useful method. De Beauvoir understands race differently from Fanon, and this difference reveals a challenge to de Beauvoir’s woman as the Other. Conversely, Fanon’s perspective on women also challenges these categories while affirming certain qualities, especially the fact that the experience of a Black woman cannot be articulated purely in de Beauvoir’s terms. Key to reading women in Fanon is recognizing that Fanon does not give an account of Black people’s otherness, but that of Black men. Fanon references Black and White women in his text, a treatment Adkins characterizes as “blatantly, even unapologetically, sexist.”[26] For Adkins, however, this sexism affirms de Beauvoir’s categorization: “Fanon determines women [...] in the very way that de Beauvoir so aptly problematizes in The Second Sex.”[27] This affirmation proves the efficacy of de Beauvoir’s method, not her categories. I put forward another interpretation that notes differences in Fanon’s tone toward Black women and White women, differences that add to the ambiguity of woman as the Other.

Fanon deals with Black women and White women in two chapters devoted to their relationships with White men and Black men respectively. Fanon is disgusted by the autobiography of a Black woman named Mayotte Capécia: Fanon resents that she supposedly “asks nothing, demands nothing, except a bit of whiteness in her life.”[28] He is derisive of Mayotte because he believes Black women only want White men: “What they must have is whiteness at any price.”[29] Fanon has purportedly known “a great number of girls from Martinique, students in France, who admitted to [him] with complete candor […] that they would find it impossible to marry black men.”[30] What is insightful is not so much what Fanon believes Black women to be; rather, it is that Fanon does not view Black women within the struggle of Black men. Indeed, by implying that Black women hold onto their sexuality as a means to approximate Whiteness and get closer to the universal subject, he reveals that he sees Black women’s sexuality as an extra layer of otherness adding to the need for “the black man to overcome his feeling of insignificance.”[31] It is then not so clear that with racialized bodies, the category of woman as the Other holds; relations between Black women and Black men seem, for Fanon, to be that of two Others who struggle differently in approximation to the universal White male subject.

"woman" by Alessandro Vannucci is marked with CC BY-NC 2.0.

"Colorfully Dressed Woman" by D-Stanley is marked with CC BY 2.0.

That Fanon’s tone toward Black women seems to oscillate between sexism and jealousy demonstrates the insufficiency of de Beauvoir’s categorization of woman as the Other. Fanon also explores the relationship between White women and Black men, a relationship that further confuses de Beauvoir’s definitive categories. Fanon’s exploration is especially pertinent if de Beauvoir’s woman is understood to be White herself. For Fanon, the site of Black man–White woman relations are seemingly one in which Black men can regain subjectivity: “Negroes have only one thought from the moment they land in Europe: to gratify their appetite for white women,” and they “tend to marry in Europe not so much out of love as for the satisfaction of being the master of a European woman.”[32] The racial and gender politics are evident: on the one hand, de Beauvoir is right. Fanon relegates woman’s role to nothing but an object to master; on the other hand, it is specifically the European woman who is satisfying to “master” because outside the intimate relationship, it is Whiteness that holds power. Fanon recounts another experience with a White woman: a White woman’s son, upon seeing Fanon, shouts “[l]ook at the nigger!” and “throws himself into his mother’s arms: Mama, the nigger’s going to eat me up”; the mother responds: “Take no notice, sir, he does not know that you are as civilized as we.”[33] Fanon’s accounts of the Black man’s relationship with the White woman is itself riddled with ambiguity. She is at once an object to be dominated, but it is the taboo of dominating the White subject that is desirable; thus, through Fanon, the White woman retains subjectivity in her race and the Black man in his gender and sexuality. The White woman and Black man are held in ambiguous relation, not in an absolute mode of subject/Other, a mode de Beauvoir’s categories fail to reconcile. However, their analyses, insofar as they are similar in recounting the multiplicity of struggles that stem from being othered by a universal subject, demonstrate their strength as a methodology for accounts of marginalized experience.

"Inde India Portrait woman femme" by etrenard is marked with CC BY-SA 2.0.

De Beauvoir’s woman as the Other is an unstable category for a number of reasons. First, de Beauvoir’s woman as trapped in a “primordial” relationship does not appear to hold as much consequence as de Beauvoir originally articulates—for Fanon, the historical independence of a collective group does not figure importantly into seeking liberation. Second, Black women’s existence problematizes the notion of woman as the Other. Black women occupy an ambiguous position, at odds with the Black man through gender and the White woman through race, as well as being othered by the universal subject in a combination of ways. If de Beauvoir and Fanon’s categories of the Other are discrete, the Black woman is incomprehensibly the other Other, the other of pure negativity. Further, the kind of acts that constitute White women’s oppressive situation are different from that of women globally. In a footnote, de Beauvoir writes that “[t]he history of the woman in the East, in India, and in China, was one of long and immutable slavery. From the Middle Ages to today, we will center this study on France, where the situation is typical.”[34] If France is typical, what, for de Beauvoir, is an atypical situation? The kind of acts constituting women’s oppression for which de Beauvoir gives an account are not obviously the same acts that constitute racialized women’s oppression (as hinted at through Fanon’s reading of Mayotte Capécia), nor even that of working-class European women. Nonetheless, the notion that oppression is constituted through instituted acts is useful. Thus reading de Beauvoir as a method for providing an account of these acts can be critical for liberatory politics.

The experiences of racialized women do not seem to fit into de Beauvoir’s notion of woman as the Other. Thus, this paper proposes that de Beauvoir’s category of the Other (as well as Fanon’s) is best understood as a method that provides an account of how lived experience constitutes oppression in acts, rather than a discrete category. That is, all on the margins are the Other; there is no universalizing framework, but the method with which de Beauvoir approaches what she believes is woman’s universal struggle can be taken up instead as a means through which a multiplicity of groups may be given a voice. Returning to Kimberlé Crenshaw, intersectional feminism recognizes the need to “include an analysis of race if it hopes to express the aspirations of non-white women.”[35] De Beauvoir’s The Second Sex still remains useful in this project if it is taken up as a method for giving voice(s) to the margins, not as an ontological category of Other, and that we need not look further than de Beauvoir’s contemporaries to begin intersectional analyses.

Endnotes

[1] Beauvoir, The Second Sex, 13.

[2] Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex, trans. H.M. Parshley (New York: Knopf, 1953), 15.

[3] Amey Victoria Adkins, “Black/Feminist Futures: Reading Beauvoir in Black Skin, White Masks,” South Atlantic Quarterly 112, no. 4 (2013): 698, https://doi-org.eu1.proxy.openathens.net/10.1215/00382876-2345243.

[4] Beauvoir, The Second Sex, 13.

[5] Ibid, 14-15.

[6] Ibid, 27.

[7] Ibid, 19.

[8] Beauvoir, The Second Sex, 17.

[9] Ibid, 18.

[10] Meryl Altman, Beauvoir in Time (Leiden: Koninklijke Brill NV, 2020), 166, Value Inquiry Book Series Online E-Book.

[11] Beauvoir, The Second Sex, 677.

[12] Judith Butler, “Sex and Gender in Simone de Beauvoir's Second Sex,” Yale French Studies, no. 72 (1986): 40, doi:10.2307/2930225.

[13] Beauvoir, The Second Sex, 677.

[14] Butler, “Sex and Gender,” 41.

[15] Beauvoir, The Second Sex, 687.

[16] Ibid, 22.

[17] Ibid, 13.

[18] Kimberlé Crenshaw, “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics,” University of Chicago Legal Forum 1989, no.1 (1989): 149.

[19] Adkins, “Black/Feminist Futures,” 719.

[20] Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks, trans. Charles Lam Markmann (London Pluto Press, 2008), 175.

[21] Beauvoir, The Second Sex, 15.

[22] Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks, 169.

[23] Beauvoir, The Second Sex, 17.

[24] Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks, 172.

[25] Beauvoir, The Second Sex, 20.

[26] Adkins, “Black/Feminist Futures,” 701.

[27] Ibid, 709

[28] Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks, 29.

[29] Ibid, 34.

[30] Ibid, 33.

[31] Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks, 35.

[32] Ibid, 50.

[33] Ibid, 86.

[34] Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex, trans. Constance Borde and Sheila Malo-vany-Chevallier (New York: Random House, 2009), 89, quoted in Stephanie Rivera Berruz, “At the Crossroads: Latina Identity and Simone de Beauvoir's The Second Sex,” Hypatia 31, no. 2 (2016): 322, https://doi.org/10.1111/hypa.12226.

[35] Crenshaw, “Demarginalizing the Intersection,” 166.