Bread, Banquets, and Capons: The Cosmopolitan Culinary Condition of Rome

By Kueh Jinhao Ryan, Yale-NUS Singapore

Introduction

At its peak, Rome was an urban city very much like cosmopolitan cities of today, featuring a rich intermingling of various cultures and religions that thrived on economic strength and growth. Scholars agree that the city contained approximately a million urban residents, with the city having an estimated consumption of more than 150,000 tons of grain per annum.[1] This, however, begs a following question. What was the quality of food for everyday Romans actually like? In most understandings of “ancient” civilizations, the rich ate better in both form and function—balanced and copious diets that contained a variety of nutritious food, whereas the poor ate the cheapest food available for sustenance.

This article seeks to explore the culinary condition of the masses and elites in Rome by comparing it to post-industrial societies. It finds that ordinary Roman citizens enjoyed a diet that was holistic, nutritious, and well-seasoned. Diets were similar in nutritional composition to the elite class, consuming food that were high in calories, diverse in choice, and flavored with spices. It presents evidence that supports a more complex culinary condition when compared to 19-20th century economies, with Roman food culture going beyond simply fulfilling nutritional necessity. Rome’s culinary condition was more alike to 21st century cosmopolitan societies, where elites distinguished themselves culinarily through the aesthetic value of consumables, pursuing food that exuded a “sense of distinction” through its copiousness or scarcity. To illustrate this trope, this paper will first expound on the diets of everyday Romans, comparing the diets with ordinary citizens of post-industrial 19-20th century European economies. It will subsequently nuance this trope by exploring the Roman intra-class culinary difference through a Bordieuan lens, analyzing the elite’s sociological behavior surrounding food and demonstrate how Rome’s culinary condition was instead more similar to the elites of modern 21st century cosmopolitan societies.

The Roman Food Pyramid

Ordinary Roman citizens ate a nutritiously balanced diet of meat, seafood, fruits, spices and grains on a regular basis, supported by large-scale import and distribution of food handouts from the Emperor.[2] The basic roman diet comprised of a main cereal portion (frumentum), supplemented with flavorful side-dishes (pulmentum or salsamentum) such as legumes, vegetables and proteins such as cheese, fish and meat.[3] The earliest Roman staple was porridge (puls) made of boiled emmer wheat, but this was gradually replaced by bread as trade grew. Meat was also available for the poor, who however often consumed less desirable parts of animals through the form of blood puddings, regional sausages (falisci, lucanicae), meatballs (isicia), or stews at food stalls and taverns. Roman cuisine was flavorful as well, with spices and seasonings such as olive oil, wine, vinegar, herbs and spices (pepper, cumin, coriander) commonly used in cooking.[4] In 123 BC, Roman quaestor Gaius Gracchus introduced the first food-related welfare handout, with the state distributing subsidized grain to the to the urban populace, eventually expanding to include olive oil, meat and wine after Severan times.[5]

This base level of welfare handouts freed up disposable income for ordinary Romans to purchase ingredients that could supplement their diets. Roman legionaries would only have to use 10-20% of his salary to purchase additional wheat for one’s subsistence and an unskilled laborer’s annual cost of feeding a family (of four) was around 20-30% of his income.[6] Literary sources suggest that urban unskilled laborers earned between 150-225 denarii between the first century BCE and CE,[7] with such wages sufficient for everyday citizens to purchase exotic spices such as black pepper priced at 4 denarii a libra. Researchers also find that Roman quarry workers were able to consume fish, shellfish, vegetables, fruits and meat,[8] where Cato’s agricultural slaves were fed a diet of an estimated 3500kcal. Archaeobotanical analysis of Herculaneum’s septic tanks supports the literary evidence on how most ordinary individuals were able to consume a flavorful and wholesome diet, where tanks linked to non-elite areas—shops, taverns and rental apartments—find traces of black peppercorn together with the remains of seafood (fish, mollusks, shellfish), meat (chicken, sheep, pigs), fresh fruits, and other spices such as coriander and poppy seeds.[9] These findings substantiate how commoners consumed a rich and varied diet despite their socioeconomic class.

"Roman Food at the British Museum - Cheesy" by vintagedept is marked with CC BY 2.0.

Comparing consumption information to post-industrial revolution cities, everyday Romans ate better than their 19th-20th century counterparts. British farm laborers during the industrial revolution spent 75% of their income on food (71% on bread) whilst miners similarly allocated 58% (40% on bread) of their income towards such purchases.[10] Other studies find that between 1787-1912, calorie consumption varied from 1685kcal to 2768kcal depending on one’s wage level (See Appendix 1), with most households suffering from some degree of nutrient deficiency with the exception of protein.[11] Further evidence from skeletal remains of Hellenistic Greece suggest a taller mean height of 172cm, whereas Western Europeans (Spaniards, Italians, and Austro-Hungarians) throughout the 18th and 19th century had a mean height of around 158-162cm,[12] with modern studies supporting the notion that height is closely correlated to nutrition—especially with the intake of high-quality proteins such as pork, fish, wheat and milk.[13] Such evidence suggests that ancient Romans were perhaps more nutritionally well-off, consuming a more wholesome diet that encouraged physiological growth. Rome thus perhaps achieved parity in food security and quality for the masses, surpassing 19th-20th Century European economies without the advantages accrued from modernization and the Industrial Revolution.

Roman “Factory” Farming

The nutritionally-dense and diverse Roman diet was only possible through the existence of complex and specialized market-oriented farms that produced livestock in large capacities, generating surplus for the masses. Domestically, the Romans were involved in a wide variety of farming practices that allowed for a rich and varied diet. Farms were technologically intensive and featured specialized farming, viticulture, arboriculture, and market gardening.[14] We see the presence of both agrarian and aquaculture practices, where entrepreneurs invested in specialized villas or latifundias—large, centrally-managed agricultural enterprises—that grew wine, olives, animals and marine culture.[15] Along the sea, there are recorded presence of maritime villas which were involved in oyster, tuna and even fish farming.[16] One such famous individual is that of eques Sergius Orata—who leased Lake Lucriunus in Campania from the Roman state for oyster farming and eventually became one of the pioneers progressive maritime farming in the Roman empire.[17]

On land, villas could range up to 2000m2 in size, an inclination of the scale and intensity of production.[18] The most prominent cash crops included olive oil and wine which were growing extensively for both consumption and export. For villas, Cato suggested that his ideal farmland size was 100 iugera (62.5 acres),[19] with certain latifundium measuring 1,000 or more iugera,[20] Concomitant to these large estates were a range of agricultural management texts devoted entirely to the maximisation of production efficiency—Cato’s De Agricultura, Columella’s De re Rustica and Varro’s Rerum Rusticarum, with Roman’s food technology comparable to the agricultural practices of leading mid-nineteenth century Europe.

If we compare food production sizes, we see that the Romans did it bigger and better than other ancient civilizations, and even 19-20th industrial societies. Columella’s benchmark for the minimum production of a well-cultivated vineyard is almost exactly the same as the average viticultural productivity of 19th-century France, with Columella’s estimates of a normal yield matching French figures for early 1950s.[21] In agriculture production, Britain’s 1885 agricultural records show that 71% of farms were under 50 acres,[22] smaller than Cato’s ideal villa size of 62.5 acres. Further, an archeozoological comparison of cattle sizes similarly show that Roman cattle sizes were sometimes similar, if not larger than cattle from the industrial era.[23] In the Bronze and Iron Ages, European cattle were small, averaging at 110cm. Following the Roman conquest, cattle sizes increased to 120cm-140cm depending on the location of the farm. In comparison, German cattle circa 1900 fell between 135-142cm, whilst cattle from many other European regions ranged from 121-126cm.

To supplement domestic production, the developed Roman global trade and expansive empire allowed for an inflow of meat, vegetable, and spices from all across the world. The empire received lettuce from Cappadocia, garum from Mauretania, game from Tunisia, edible flowers from Egypt, and also imported figs from Africa.[24] One of the most impressive spices includes the import of black pepper from the Indo-Roman trade. Spices were imported in bulk, allowing such exotic goods to be available at a cheaper price, servicing a much broader segment of the population than anticipated.[25] According to Pliny, the empire imported 50 million sesterces of pepper annually.[26] The distribution of staple foods thus freed up income, allowing everyday citizens to purchase affordable “luxury” spices and vegetables that were imported. The confluence of large-scale domestic production and massive logistical structures thus allowed for food to be produced and imported on an industrial scale, creating surplus that enabled a variety of food to be affordable for the masses and encouraging a holistic and varied diet.

The Habitus of Consumption

Thus far we have seen how the Roman commoner had a similar nutritional diet composition to the rich, requiring us to draw a more nuanced analysis to illustrate the differences between classes, in terms of food consumption. To aid us in this endeavor, modern sociologist Pierre Bourdieu writes on how food has become an identifier and signifier of one’s class. Bourdieu’s concept of class habitus aptly explains this, where the “the aesthetic sensibility that orients actors’ everyday choices in matters of food, clothing, sports, art, and music […] serves as a vehicle through which they symbolize their social similarity with and their social difference from one another”.[27] Members of the dominant class lead a lifestyle that prided on form over function, through a “sense of distinction” via social, cultural, and economic capital, where conversely, members of the working class develop a “taste for necessity”—characterized by a lifestyle of function over form.[28]

The main difference between the diets of the rich and the poor is therefore not in nutritional value (function) but in aesthetic form. As previously discussed, the common citizen had a diet that included handouts—wine, bread, olive oil—supplemented by access to cheese, fresh vegetables, fruits, vegetable protein and meat in the form of off-cuts. Horace and Marital record how chickpeas, lentils, and fava beans were frequently served both at home and at inexpensive food stalls in the city.[29] The rich similarly often consumed such vegetable protein, accompanied with choice cuts of meat such as pork, beef and lamb. Fish was also consumed by both classes, albeit for the lower class this was in the form of preserved fish sauce or garum, whereas the rich in the form of fresh fish. Fresh fish commanded large sums in the imperial period, with Seneca recording up to 5,000 sesterce for one mullet and Pliny up to 8,000 sesterce.[30] On occasion, the aristocratic class was also known to consume exotic meats—wild game, song birds, dormice and flamingo.[31] Foie Gras was also referenced to by Pliny the Elder, where a goose is force-fed to fatten the liver before removing the liver and further enlarging it by soaking the organ in honey-sweetened milk.[32] Thus, although both classes had a diet with similar compositions, the rich had a wider variety of dishes and access to fresh food that was unmatched by commoners.

The difference thus lies in the aesthetic value of consumables rather than the function, where the Roman elites—similar to modern cosmopolitan elites—often used a “sense of distinction” with food as a medium to distinguish themselves from the lower classes, with food now becoming a marker of class through social, cultural, and economic capital. This form over function came in two manifestations: 1) Banquets and 2) Needless Exoticism of Food.

Banquets or “Buffets”

Banquets were a potent symbol of culture where the Romans had a large practice of feasting for the entertainment of the people during celebratory and religious occasions.[33] Aemilius Paullus’ famously organized a banquet to celebrate his victory over the Macedonians in 167 BCE, where he was noted to say “the man who knows how to conquer in war can also arrange a banquet (conuiuium) and organize games”.[34] Banquets had a diplomatic function of advertising Rome’s power—demonstrating an individual and empire’s organizational skills and showing cultural understanding before an assembly of surrounding powers. It signaled economic capital, where only civilizations that had additional surplus were able to carry out such feasts, whilst assisting elites in reproducing cultural capital through the recurrence of banquets.

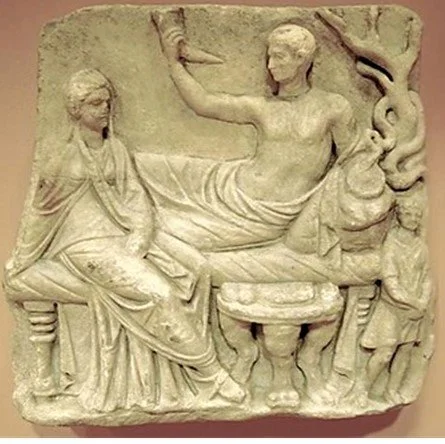

"Funerals Grave relief showing the deceased and his widow in a funeral feast where they are depicted in a godlike manner Roman 1st century CE WM McLeod 720X480" by mharrsch is marked with CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Banquets not only had political function, but a social one as well. Philanthropy (Philanthropia) was expected of Roman elites, where they had to maintain large networks of social connections and entertain visitors who came to the city with recommendations from friends. This usually involved feeding and entertaining these large crowds, where certain norms dictating these gatherings. For example, when dining with intimate friends, the capacity should not exceed nine people for it was believed that the occasion would be unruly, going from convivium (life-sharing) to convitium (vice-sharing).[35] During these banquets, aesthetic form was also important, where the way food was served and appeared carried salience. Slaves were trained in proper serving and carving techniques, with such a role famously elucidated by Carver the Carver in Trimalchio’s dinner.[36] Apicius, one of the authorities on food, also gave instructions on how food should be served, recommending an expensive silver platter for plating.[37]

In Petronius Satyricon featuring Trimalchio—a former slave who has turned rich and is famed for hosting elaborate, ostentatious banquets—is known to interrupt Seleucus and Habinnas mid-conversation to ask: “But what did they give you to eat?”,[38] referring to another party Seleucus and Habinnas were coming from. This is meant to satirically illustrate how for elites, what one consumed was of over-inflated concern. Petronius further ridicules Trimalchio’s lack of sophistication and finesse in the realm of food and wine, where despite having the wealth to spend on such lavishness, he draws out contrasts between the money spent on the food and the insipid end result [39]. One common example was how elites determined a host’s social hierarchy depending on whether oysters were served at a banquet.[40] Trimalchio’s lack of finesse in form was thus scoffed by Petronius, where the former slave lacked cultural capital of a true “elite”. We thus can see how banquets were utilized within the elite milieu to reproduce social capital whilst demonstrating economic and exclusive cultural capital.

Capons and Ortolans

Next, we see the presence of the needless exoticism of food, where elites ate items as a status symbol rather than for function. In Rome, the aristocratic class was known to consume exotic meats—wild game, song birds, dormice and flamingo, where these exotic meat were priced for its opulence and fetishized by elites not due to its taste, but rather its limited supply and high price. We see parallels to modern day consumption of exotic meat and its ancillary moral concerns, with some examples shark fins, ortolans and pangolin meat. The rarity of these animals often stem from its illegal status and immoral preparation techniques—which in turn makes these dishes even more exotic. One contentious example is modern Foie Gras, with the dish often drawing criticism from its gavage preparation technique—goose or ducks force-fed with a 15-inch tube to facilitate indigestion, unnaturally fattening the livers directly which ensures a desirable texture. Another example is that of ortolans, a practice that has been banned but is still popular on the black market.[41] In Rome, the Lex Faunia was introduced in 162 BC to forbid citizens from eating fattened hens in an attempt to save grain. Roman farmers then found a way around this through caponisation—the castration of cockerels which allowed the animals to put on weight and grow twice their normal size,[42] with the consumption and practice of fattened pullets subsequently banned.[43]

Roman and modern civilizations share similar approaches in morally questionable modifications of the animal to produce more “delicious” meats and ancillary pushbacks stemming from animal morality. First, in both civilizations there is an interest and intricate understanding of animal biology, where farmers went beyond simply feeding the livestock, and experimented various ways to produce animals specific for exotic consumption—producing animals that were plumper or with fattier livers than the one’s produced by conventional means. Secondly, we similarly see how authorities attempted to clamp down on such “excessively cruel” practices. In Rome, we see the introduction of laws[44] in an attempt to curb such behaviors, with these laws attempting to control frivolous consumption, consumption expenditure and banned certain foods such as fattened pullets and dormice [45]. The banning of shark fins and ortolans are similar modern examples, where these laws sought or are still seeking to ban the overconsumption of these delicacies due to ethical and animal-welfare concerns. Thus, we see similarity between Roman and modern elites in their desire to distinct themselves through needless exoticism of certain food, where such delicacies allow them to convey a “sense of distinction” and demonstrate economic capital and an exclusive cultural capital.

Juvenal – Sociologist in Antiquity

In Rome, excessiveness and frivolous spending on banquets and exotic food concomitantly drew scrutiny amongst many, with moralizing literature in the form of satire and philosophical work denouncing extravagance as indicative of moral decay. Juvenal’s infamous term “bread and circuses” speaks to the corruptibility of the citizenry via food and games,[46] where Emperors used food and entertainment as one method of issuing rent to prevent the people of Rome from revolting. The critique focuses on the citizen’s primal desire for such simplistic demands, a commonality found in both elites and locals albeit in different forms. In Horace’s dinner invitation poem addressed to Persicus, Horace talks about the fine wine and food they consume.[47] Juvenal mocks such excessiveness and “softness”, mentioning how gourmet habits would leave one suffering when one’s wealth has been spent and is unable to satisfy one’s desire again,[48] where food has evolved into a symbol of corruption and gaudiness. He also contrasts how Roman predecessors did not engage in such opulence, insinuating how “honorable” leaders of today are “soft”, whereas the original Roman heroes were “tough”, pragmatic and did not concern themselves with these luxuries.[49]

Bourdieu’s theory, which illustrates the class condition of modern society, is interestingly also applicable to Roman society, where both modern and ancient literature demonstrate consensus that the main difference between the classes is not in nutritional value but in aesthetic form. Due to the balanced and rich diets of the commoners, the “sense of distinction” for elites were thus focused on form rather than function, with elites pushing for aesthetic extravagance and gaudy exoticness. This was exclusive to elites as only through their wealth could they afford exotic meats and banquets (economic capital), allowing them to create a distinct culture (cultural capital) that is reproduced through a closed social circle (social capital).

Conclusion

In conclusion, the everyday citizen in Rome did not only consume for sustenance or “necessity”, but enjoyed a diet that was wholesome, nutritious and well-seasoned, similar in function to the elite class. Ordinary Romans ate well, driven by welfare handouts and additional surplus due to the large specialized agricultural industry of Rome. This pushed the elites to form distinguishing factors along class-based cleavages, with Roman elites distinguishing themselves in form rather than function, focusing on aesthetics through banquets and needless exoticism that could show and reproduce their economic, social, and cultural capital. As such, the Roman culinary condition was perhaps superior to 19-20th century economies, and more like 21st century cosmopolitan cities in both form and function. This analysis of the Roman culinary condition draws similarities between the class-based sociological structures of Rome and modern contemporaries, prompting one to rethink the intricacies and modernity of class structures, and perhaps prompt a deeper reflection into our common historical condition.

Endnotes

[1] Paul Erdkamp, “The Food Supply of the Capital,” in The Cambridge Companion to Ancient Rome (Cambridge University Press, 2013), 262–77, https://doi-org.libproxy1.nus.edu.sg/10.1017/CCO9781139025973.

[2] Geoffrey Kron, “Food Production,” in The Cambridge Companion to the Roman Economy, ed. Walter Scheidel, Cambridge Companions to the Ancient World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 156–74, https://doi.org/10.1017/CCO9781139030199.011.

[3] J. Mira Seo, “Food and Drink, Roman,” in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome (Oxford University Press, 2010), http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195170726.001.0001/acref-9780195170726-e-490.

[4] Seo.

[5] Erdkamp, “The Food Supply of the Capital.”

[6] Geoffrey Kron, “Comparative Evidence and the Reconstruction of the Ancient Economy: Greco-Roman Housing and the Level and Distribution of Wealth and Income,” 2014, 123–46, https://doi.org/10.4475/744.

[7] Ernst Emanuel Mayer, “Tanti Non Emo, Sexte, Piper: Pepper Prices, Roman Consumer Culture, and the Bulk of Indo-Roman Trade,” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 61, no. 4 (May 24, 2018): 560–89, https://doi.org/10.1163/15685209-12341464.

[8] Kron, “Comparative Evidence and the Reconstruction of the Ancient Economy.”

[9] Mayer, “Tanti Non Emo, Sexte, Piper.”

[10] Emma Griffin, “Diets, Hunger and Living Standards During the British Industrial Revolution*,” Past & Present 239, no. 1 (May 1, 2018): 71–111, https://doi.org/10.1093/pastj/gtx061.

[11] Ian Gazeley and Sara Horrell, “Nutrition in the English Agricultural Labourer’s Household over the Course of the Long Nineteenth Century,” The Economic History Review 66, no. 3 (2013): 757–84, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0289.2012.00672.x.

[12] Kron, “Food Production.”

[13] Jessica M Perkins et al., “Adult Height, Nutrition, and Population Health,” Nutrition Reviews 74, no. 3 (March 2016): 149–65, https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuv105; P. Grasgruber et al., “The Role of Nutrition and Genetics as Key Determinants of the Positive Height Trend,” Economics & Human Biology 15 (December 1, 2014): 81–100, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2014.07.002.

[14] Kron, “Food Production.”

[15] Emanuel Mayer, “Money Making, ‘Avarice’, and Elite Strategies of Distinction in the Roman World,” in Skilled Labour and Professionalism in Ancient Greece and Rome (Cambridge University Press, 2020), 94–126, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108878135.004.

[16] Annalisa Marzano, “The Variety of Villa Production From Agriculture to Aquaculture,” in Ownership and Exploitation of Land and Natural Resources in the Roman World (Oxford University Press, 2015), http://oxford.universitypressscholarship.com/view/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198728924.001.0001/acprof-9780198728924-chapter-11.

[17] Pliny Nat. Hist 9.168–9; Cic. Hort 67–71

[18] Antoni Martín i Oliveras and Víctor Revilla Calvo, “The Economy of Laetanian Wine: A Conceptual Framework to Analyse an Intensive/Specialized Winegrowing Production System and Trade (First Century BC to Third Century AD),” in Finding the Limits of the Limes: Modelling Demography, Economy and Transport on the Edge of the Roman Empire, ed. Philip Verhagen, Jamie Joyce, and Mark R. Groenhuijzen, Computational Social Sciences (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2019), 129–64, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-04576-0_8.

[19] G. E. Fussell, “Farming Systems of the Classical Era,” Technology and Culture 8, no. 1 (1967): 16–44, https://doi.org/10.2307/3101523.

[20] Annalisa Marzano, Roman Villas in Central Italy: A Social and Economic History, Roman Villas in Central Italy (Brill, 2007), http://brill.com/view/title/14257.

[21] Varro, Rust. 2.3.10; Kron, “Food Production.”

[22] J. V. Beckett, “The Debate over Farm Sizes in Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century England,” Agricultural History 57, no. 3 (1983): 308–25.

[23] Geoffrey Kron, “Archaeozoological Evidence for the Productivity of Roman Livestock Farming,” MBAH 21 (January 1, 2002): 53–73.

[24] Phyllis Pray Bober, Art, Culture, and Cuisine: Ancient and Medieval Gastronomy, 1st edition (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001); Patrick Faas, Around the Roman Table: Food and Feasting in Ancient Rome, trans. Shaun Whiteside (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2005), https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/A/bo3534520.html.

[25] Mayer, “Tanti Non Emo, Sexte, Piper.”

[26] Pliny Nat. Hist 12.28 and 58

[27] Pierre Bourdieu, Practical Reason: On the Theory of Action, trans. Randall Johnson (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1998), http://www.sup.org/books/title/?id=2043; Elliot B. Weininger, “Pierre Bourdieu on Social Class and Symbolic Violence,” Alternative Foundations of Class Analysis 4 (2002): 138.

[28] Pierre Bourdieu, Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste (Harvard university press, 1984).

[29] Seo, “Food and Drink, Roman.”; Horace Satires 1.6; Martial 5.78

[30] Seneca, Epistles, 95.42; Pliny Nat. Hist, 9.67.

[31] Seo.

[32] Pliny Nat. Hist, 10.52

[33] Beryl Rawson, “Banquets in Ancient Rome: Participation, Presentation and Perception,” in Dining on Turtles: Food Feasts and Drinking in History, ed. Diane Kirkby and Tanja Luckins (London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2007), 15–32, https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230597303_2.

[34] Livy, 45. 32–3

[35] Veronika E. Grimm, “On Food and the Body,” in A Companion to the Roman Empire (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2006), 354–68, https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470996942.ch19.

[36] Petronius, 36, 7-8

[37] Apicius 4.141

[38] William Arrowsmith, “Luxury and Death in the Satyricon,” Arion: A Journal of Humanities and the Classics 5, no. 3 (1966): 304–31.

[39] Grimm, “On Food and the Body.”

[40] Marzano, “The Variety of Villa Production From Agriculture to Aquaculture.”

[41] Ortolans are caught and deprived of light, causing the bird to gorge on grain and fattening themselves up. The birds are then drowned, and/or rather, marinated in Armagnac before they are roasted and consumed whole—head, bones and feet included—in one bite. Diners traditionally veil their face with a napkin before consuming the chicken—a symbolic gesture to mask the shame of eating the ortolan from the eyes of god.

[42] Maguelonne Toussaint‐Samat, “The History of Poultry,” in A History of Food (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2008), 305–30, https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444305135.ch11.

[43] Seo, “Food and Drink, Roman.”

[44] Lex Fannia in 161 bce, Lex Licinia in 103 bce, Lex Cornelia of Sulla in 80 bce and lex Julia in 1 bce

[45] Seo, “Food and Drink, Roman.”

[46] Juvenal, Satire 10.77–81; Erdkamp, “The Food Supply of the Capital.”

[47] Horace 1.5, 1-15

[48] Juvenal 11, 30-43

[49] Juvenal 11, 90-100 & 120-125