Call of the Distant Mountains

BY ZHI ZHANG, WELLESLEY COLLEGE

In 1279, the last lingering hope of Southern Song was annihilated as the Mongolian warmongers triumphed in the naval battle of Yamen. Kublai Khan declared the establishment of the Yuan Dynasty, and China, for the first time, fell to foreign rulership. It is a subject that still puzzles the scholars today as to how one of the most epochal periods of Chinese culture prospered under the reign of “barbarous” alien nomads. The artistic creativity of the Yuan scholar-artists was not strictly circumscribed by the already well-established pictorial conventions. Rather, they strove to make the past serve the present. Among them stood the most pivotal figure at the turn of the 13th century - Zhao Mengfu, whose reputation had long been tormented by his active service in the Mongolian court despite his identity as a royal descendent of the past Song dynasty. Notwithstanding his loyalty issues, Zhao’s artistic contributions were undeniably prodigious. A comparative study between Zhao Mengfu’s Twin Pine, Level Distance of ca. 1310 (Fig. 1) and Guo Xi’s Old Trees, Level Distance of ca. 1080 (Fig. 2) reveals two of Zhao’s most acknowledged theories: first, his commitment to cultural archaism (fugu 复古) and seeking of “antique spirit” (guyi 古意) in paintings; second, his instrumental synthesis of calligraphy and painting techniques (yishu ruhua以书入画). Collectively, they attested to Zhao’s ingenuity in dialogue with the ancient, as well as his revolutionary approach in revitalizing the history and rendering it anew.

Zhao Mengfu was not the first to advocate the search for guyi. Yet, his archaism was not a schematic reproduction of prototypes but a refreshing and original reinterpretation of the cannon. The aim was to breathe new life, or “spirit resonance” (qiyun 气韵), into paintings in order to deprive them of the lingering academic orthodoxy. He wrote in 1301:

“The most precious quality in painting is the antique spirit [or conception]. If this isn’t present, the work isn’t worth much, even though it may be skillfully done. Nowadays, people who paint in a detailed and delicate manner with bright colors consider themselves to be proficient artists. They are unaware of the fact that works lacking antique spirit aren’t worth looking at. My own paintings may seem to be quite simply and carelessly done, but the true connoisseur will recognize that they adhere to old models and are thus deserving of approval. I say this for connoisseurs and not for ignoramuses.” [1]

Figure 1. Zhao Mengfu (1254–1322), Twin Pines, Level Distance, ca. 1310, Handscroll, ink on paper, 10 9/16 x 42 5/16 in. (26.8 x 107.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Ex coll.: C. C. Wang Family, Gift of The Dillon Fund, 1973

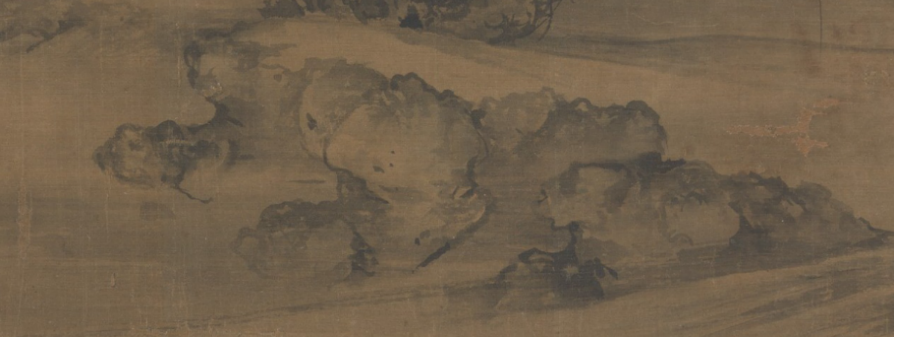

Figure 2. Guo Xi (ca. 1000–ca. 1090), Old Trees, Level Distance, ca. 1080, Handscroll, ink and color on silk, 14 × 41 1/8 in. (35.6 × 104.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Gift of John M. Crawford Jr., in honor of Douglas Dillon, 1981

The inscription offered a lucid explanation of his theory, clearly stating his loathing for the recent ostentatious styles and at the same time, nodding to the canon of old masters. In lieu of scrupulously abiding by one single style, Zhao combined merits across different masters and selectively revived the past. Apart from its theoretical importance, Zhao’s classicism was also instrumental in purging the remnant obsequiousness and decadence of Southern Song Academy art, which he might as well have read as a harbinger with the fall of the dynasty. Juxtaposing Zhao Mengfu and Guo Xi’s two seemingly similar landscapes elucidates Zhao’s selective quotation from, as well as deliberate revision on, the past model — explicitly invoking Guo Xi’s composition and motifs, Zhao boldly reduced imageries to be painted at a minimal level and left most space empty.

At first glance, the two paintings closely resemble each other with respect to their composition. They share the vista of “level-distance”, which is achieved by setting the viewpoint on a nearby mountain to gaze at one in the distance as defined by Guo Xi himself. Landscape in level-distance is oftentimes associated with the format of a handscroll, which presents a stark contrast with the monumental landscape in large hanging scrolls — with Guo Xi’s Early Spring was a pinnacle exemplar. Monumental landscapes were political metaphors of ideal Confucian court hierarchy — in which the paramount peak symbolized the emperor — and eulogies for the prosperous society under his rulership. By contrast, preeminent mountain is absent in level-distance layouts, which signals one’s momentary detachment from petty officialdom [2]. Foong Ping identifies Guo’s Old Trees to be an intimate work dedicated to his literati friends who, in turn, read from his quivering autumn scenery a “nostalgic longing” and a melancholic, embittered sentiment toward the court [3]. Well-versed in the multilayered undertone of level-distance format, Zhao Mengfu had the opportunity to see in person Guo’s Old Trees and in his colophon (Fig. 3) — a written inscription of commentaries attached as an additional page to the scroll — he noted:

“Tall mountains and flowing rivers fill the world,

Aspiring to draw them with water and ink is difficult.

My whole life I have followed the lofty message of forests and steams;

Constrained by petty official duties, I have been unable to achieve it.” [4]

Figure 3. Zhao Mengfu, colophon attached to Guo Xi, Old Trees, Level Distance.

Zhao’s own Twin Pines was probably painted after he had been summoned back to the court for the second time in 1309 by Emperor Renzong [5]. He had gone on a long sojourn to Dadu (present day Beijing), the Yuan capital far away from his home Wu Xing (present day Hu Zhou, Zhe Jiang province) twice now. Emperor Renzong was fervent in Zhao and compared him to the great scholar-artists like Li Bai and Su Shi [6]. Nevertheless, Renzong never assigned Zhao to any significant political post, as Khan once did. In fact, Zhao was mainly in charge of artistic and cultural duties during Renzong’s reign. Therefore, it is reasonable to date Zhao’s colophon to an early stage of his career, and his Twin Pines, a later time. Maxwell Hearn denotes chaoyin (朝隐) as what characterizes Zhao’s career - “becoming an official but detaching… and maintaining the moral purity of a hermit”. The sense of detachment finds its counterpart in Guo's intimate landscape as well, but Zhao rendered it differently and quite innovatively.

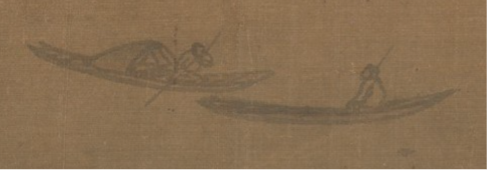

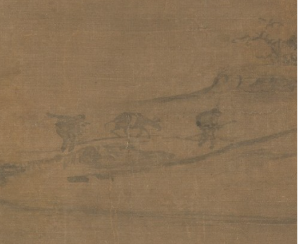

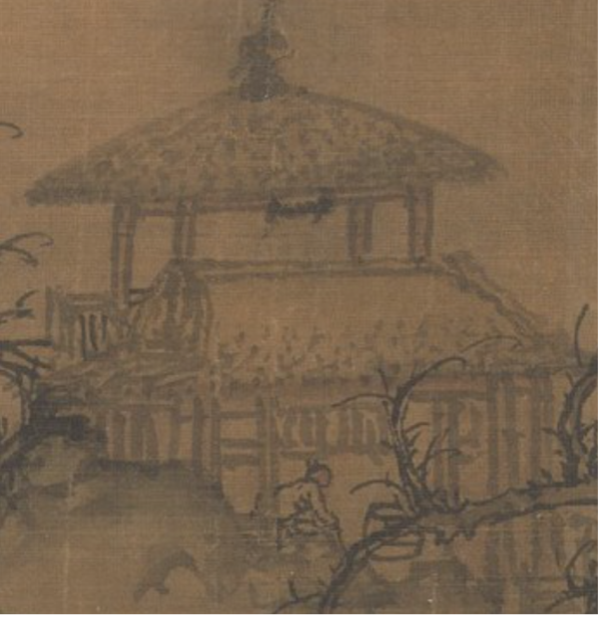

Despite the political vicissitudes, Zhao was nevertheless luckier than his southern literati peers to have access to the collection of Northern School old masters like Li Cheng and Guo Xi during his stay in Dadu. Twin Pines manifests the Li-Guo formula of a tripartite “hills beyond a river” plan [7] - trees and rocks occupying the shore in the foreground, a river creating the sense of spatial recession in the midground, and misty distant mountains in the far background. The layout is diagonal in both Zhao’s Twin Pines and Guo’s Old Trees, but the opposite directions convey completely different messages. Guo Xi’s design is well calculated - the island, mountains, pavilion, shore constitute a stable trapezoid compositional framework. It is also self-contained - one starts the scroll of Guo Xi with distant mountains at the upper right and unfolds until the leftmost edge where the figures traveling to the right redirect the view back into the landscape (Fig. 4). On this wise, Guo Xi’s painting evokes rationality and order, as was typical of his contemporary landscapes. On the contrary, the layout in Zhao’s is much more uninhibited. The large foreground covers the entire space on the rightmost section and thus captures the visual focus. The islands and mountains are depicted in parallel linear forms, suggesting they are within proximity to one another, thus obscures the boundary between midground and background. Connecting the direction of one of the pine branches, the islands run all the way across the scroll as though, if not limited by the dimension, they can extend beyond the physical surface. Opposite to the carefully calculated design of Guo, Zhao Mengfu breaks the paradigm of the three-part plan and reveals unbridled spontaneity in the landscape.

Figure 4. Guo Xi, Old Trees, Level Distance, detail of figures traveling into the landscape.

Let us remind ourselves of Zhao’s role in the Mongolian court — as a descendent from the Song imperial line, to turn to serve the enemy of non-Han ethnicity was morally and ethically unacceptable, especially given that many of his peers from Wu Xing resolutely rejected the invitation of Yuan court. Yet it was not without considerations for the well-beings of his people that Zhao eventually set foot in Dadu under Khan’s call. Afterall, to advise the ruler in upholding righteousness is, ultimately, to enhance the lives of people, whereas being a cynical hermit contributed none. The History of Yuan documented Zhao’s immense achievement in assisting the tax reform during Khan’s rule [8]. By the time of Emperor Renzong, however, Zhao’s bureaucratic responsibilities were truncated. We could only imagine how conflicted Zhao must have felt to be constrained in a foreign government where only his art was valued. The vast voidness in the painting thus should be read as a reflection of the chaoyin mentality of the artist, who probably yearned for a tranquil spiritual residence where he could temporarily withdraw from the exhausting confinement of political intrigue.

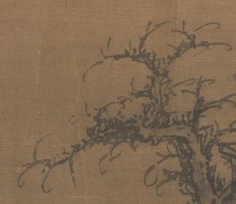

Figure 5. Zhao Mengfu, Twin Pines, Level Distance, detail of pine and samplings.

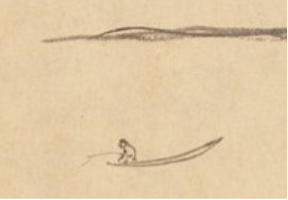

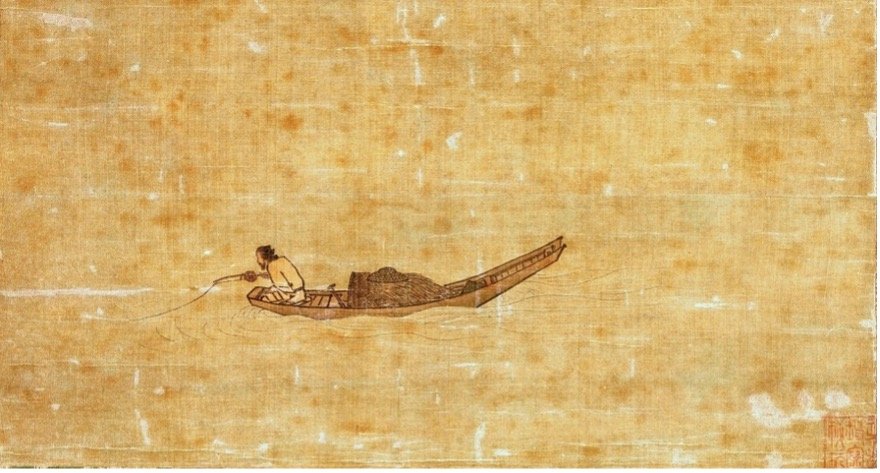

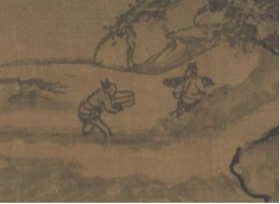

The conscious selection by Zhao from Guo’s motif repertoire also exhibits his tendency toward minimalism, which laid profound influence for the late literati artists, especially Ni Zan. It is worth noticing that the term minimalism is not to be confused with its canonical definition in Western art history. Literati artists did not purposefully seek abstract forms, they seeked succinct portrayal of outer reality, and their contemplation, most importantly, was to be conveyed in the very lack of imagery. The basic elements of a landscape — rocks, trees, mountains and river — are present in both artists’ works but in different forms. The pavilion and the stone bridge of Guo Xi have been eliminated by Zhao, and the multiple figures have been reduced to a singularity. For Guo Xi, capturing the nuances of seasons and times are quintessential to his natural landscapes. Thus, the withered vines on old, gnarled trees and misty mountains are typical of him as an indication of an autumn evening scene. On the contrary, signs of naturalness are obscure in Zhao’s scroll. He painted tall straight pine trees with unnaturally downward-stretching branches that makes it difficult to demarcate the exact season — is it summer as the tree trunks are robust and thriving, or is it winter since the branches are bowing (Fig. 5)? The bone-like saplings protruding from the rocks are ambiguous as to whether they are withering or sprouting. The evergreen character of pines further deemphasizes the need to specify a season in his painting. Leaving no trace of mist or atmosphere, the simplistic forms of distant hills minimize the sense of temporality, too. Additionally, both artists utilize empty space to allude to the river flow and confirm its existence with protruding islands and fishing boat(s). In Twin Pines, the lonely fisherman drifts on more spacious emptiness and seems to be enveloped by void, evoking extreme solitude and vulnerability (Fig. 6). Recalling Ma Yuan’s Angler on a Wintry Lake of 1195 (Fig. 7), this use of blank space has already been fully exploited. But Zhao rejects Ma’s accuracy and precision — specifically the naturalism in human and water ripples, which, to his taste, are defects of academic dogma. The figure in Zhao’s painting calls upon a sense of primitivity and candidness suggests communal actions, with lines of sight directed toward one another (Fig. 8 - 11). The only figure that appears on himself is also implicitly connected to the community as it looks like he is preparing for their arrival (Fig. 12). Foong Ping notes that even the birds and trees occur in pairs and asserts that the iconography of paired inhabitants is a metonymy of the patron-painter relationship [9]. Unlike Guo Xi, whose customized landscape aims to evoke emotional resonance of literati friends who share similar experiences by narrating a perceptible story in his subject matter, Zhao “has eliminated the emotion-laden atmospheric and narrative details of the earlier work” [10] by removing the pavilion stone bridge and excess figures. Although Guo Xi’s landscape contains figures actively engaging each other, it ultimately conveys a bittersweet pre-departure melancholy, whereas Zhao’s landscape, though cool and spare, is unpretentiously elegant and imparts a feeling of nonchalance that, again, accords with the idea of chaoyin. In other words, Zhao paints solely under self-expression, which fundamentally distinguishes him from Guo Xi, who is patron-driven, private or imperial regardless.

Some judged that Zhao Mengfu is never amongst the top-ranked artists, arguing that his artistic achievement were limited due to the overt obsession with past canons [11]. Yet, Richard Vinograd, who criticizes harshly of Twin Pines’s formalistic deficiencies in his essay, still acknowledges that “Zhao Meng-fu’s transformations of the manner are evidence of his historical understanding of past art, of his characteristic process of adaptation of old styles, and of what is original within his often archaistic and tradition-keeping art” [12], as also discussed above. To further investigate Zhao’s originality and creativity, it is necessary to examine Zhao’s application of the synthesis of calligraphy and painting (以书入画) — another revolutionary artistic theory of his — in Twin Pines.

Figure 6. Zhao Mengfu, Twin Pines, Level Distance, detail of fisherman. | Figure 7. Ma Yuan (1160-1225), Angler on a Wintry Lake, 1195, 141 x 36cm. Tokyo National Museum. | Figure 8. Guo Xi, Old Trees, Level Distance, detail of fishermen pair. | Figure 9. Guo Xi, Old Trees, Level Distance, detail of old man-servant pairs.

Figure 10. Guo Xi, Old Trees, Level Distance, detail of servants pair. | Figure 11. Guo Xi, Old Trees, Level Distance, detail of woodcutters pair. | Figure 12. Guo Xi, Old Trees, Level Distance, detail of the only figure that appears on himself.

Most straightforwardly, the synthesis is exemplified by literally writing the long inscription in the same pictorial space with the painting, as opposed to on a separate sheet of paper that is later attached to the scroll. A zoomed-up image of the colophon clearly shows the calligraphy is already overlapping with the strokes of the mountain (Fig. 13). It becomes so crucial- a part of the entire composition that, with its removal (Fig. 14), the composition mislays its visual stability since Guo Xi’s trapezoid layout is not kept intact here. The long inscription takes up the entire vertical slot on the left, therefore remotely echoing the large foreground on the right. Artist’s inscription on their painting is a tradition established well before Zhao’s time, yet the content of Zhao’s is unusual - it is not a narrative anecdote or a poem, but an art historical commentary that candidly reinforces his favour of old masterpieces over “recent painters”. The function of a colophon has evolved from merely adoring the poetic qualities of natural landscapes to asserting the selfhood of an artist. Accordingly, this very colophon epitomizes the communion of both of Zhao’s major theories — lacing together text and image, the former professes his motivations behind cultural archaism and the latter, his praxis.

Figure 13. Zhao Mengfu, Twin Pines, Level Distance, detail of colophon overlapping with painting.

Figure 14. Zhao Mengfu, Twin Pines, Level Distance, colophon removed.

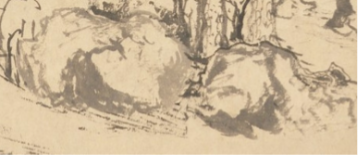

On a more profound level, the synthesis refers to the conception of calligraphy and painting coming from the same origin (书画同源), which also arose well ahead of Zhao. But as the most accomplished calligrapher of Yuan, if not of all times, he is the most pivotal figure considering the instrumental vocabulary of calligraphic brushstrokes he has established. After his painting Elegant Rocks and Sparse Trees of 1300, Zhao wrote down one of the most influential colophons in the development of literati paintings: “Rocks like Flying-white, trees like the Great Seal script; the sketching of bamboos should include the eight Strokes of calligraphic technique” [13]. Flying-white is a technique in calligraphy that is produced when the brush moves so swiftly that the drying hair begins to separate, thus leaving blank spaces from within the ink. Outlines of rocks in Twin Pines brilliantly exhibit the application of this technique in landscape elements (Fig. 15-16). Their left edges are emphasized with broader ink, invoking the use of cefeng (侧锋) - writing with the side of brush hair - and hence produce more variation of texture than the thinner linings of the right sides. The flying-white fabricates the shape but refrains from substantiating any interior volume. In general, it produces an effect of perfunctoriness but also highlights the artist’s hand and his impulsive execution.

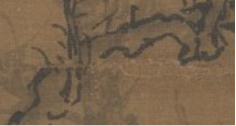

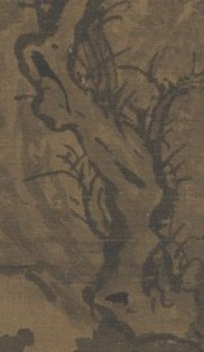

By contrast, the outlines of Guo’s rocks are results of sophisticated but realistic representations of nature - angular and jagged, they concur with the late autumn bleakness on the one hand and, on the other hand, “demarcates space below and behind the rock” [14] (Fig. 17). The ink washes varied meticulously in accents and gradations to build naturalistic volumes. The convention of adding texture using cun (皴) is conspicuous in the shoreland (Fig. 18), but Zhao clearly has decided not to pay homage to this “un-calligraphic” technique. The two artists deviate even more greatly in the depiction of trees. Guo’s gnarled old trees are realistically rendered, with outlines of alternating thickness and intermittent breaks (Fig. 19 - 20) that makes evidence of the artist’s careful planning as he employs the brush. The branches demonstrate Guo’s renowned “crab-claw” (蟹爪枝) technique (Fig. 21) - tangling with each other, faithfully reporting the tree types prevalent in Northern areas. Zhao, in line with his didactic quote, invokes the style of zhouwen (籀文), or Great Seal Script (大篆). The contour of twin pines (Fig. 5) runs across the paper within one stroke, non-stop, leaving no room for pause and re-planning thus manifesting spontaneity. The varied thickness and zigzag brushwork of Guo is replaced with the rounded and uniform outline, which are more suitable for depicting tall and straight pines. This approach bears immediate reference to seal script writings, as can be seen in Zhao’s own Record of the Miaoyan Monastery (Fig. 22). “Crab-claw” technique is faintly visible in Zhao’s handling of the saplings, but he dredges Guo’s straggled branches into arrayed skeletons. Cursory at first glance, the sapling de facto reflects the artist’s superb control of his brush, which is comparable to Zhao’s distinguished running-cursive script (Fig. 23 - 25). The brushwork is charged with vigour and composed elegance, running fluently yet displaying rhythmic flexibility. Moreover, Zhao’s mountains are also exemplary of calligraphic painting.

Figure 15 (left), Figure 16 (right). Zhao Mengfu, Twin Pines, Level Distance, details of flying-white technique on rocks | Figure 17 (left). Guo Xi, Old Trees, Level Distance, detail of rock’s outline. | Figure 18 (right). Guo Xi, Old Trees, Level Distance, detail of cun (皴).| Figure 19 (upper left). Guo Xi, Old Trees, Level Distance, detail of pulsing thickness.| Figure 20 (right). Guo Xi, Old Trees, Level Distance, detail of pulsing thickness. | Figure 21 (lower left). Guo Xi, Old Trees, Level Distance, detail of crab-claw technique.

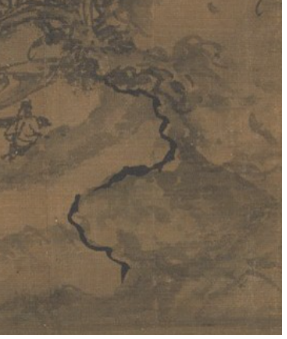

The way Guo suggests mist and remoteness is by applying diluted ink wash blocks, to give form to mountains while muting their outlines (Fig. 25). However, Zhao radically rejects any interior texture and chooses to keep only the outline (Fig. 26). Naturalistic texture and volumes give way to calligraphic linearity. Despite the fact that Zhao painted Twin Pines when he was in Dadu, his gently-sloped hills are poles apart from Guo’s precipitous peaks while the latter evokes the topography of the Taihang mountains (Guo’s hometown, also in proximity to Dadu) whereas the former resembles more likely of the Jiangnan (江南) region. Within a few pale-inked brushstrokes, Zhao outlines not what is in front of his eyes but perhaps a nostalgic mind-landscape of his hometown. Shallow in form but definite in clearly outlined existence, they echo the enduring pine trees in the foreground and await the artist’s homecoming.

Figure 22. Zhao Mengfu, section from Record of the Miaoyan Monastery, ca. 1309–10, handscroll, ink on paper, 34.2 x 364.5 cm. (13 7/16 x 143 1/2 in.), Princeton University Art Museum. Bequest of John B. Elliott, Class of 1951

The effect of unifying calligraphy and painting is twofold. First, it is a means through which Zhao tries to achieve antique spirit. Drawing inspiration from diverse calligraphic models, he was able to synthesize disparate styles into an original one - zhaoti (赵体). Analogously, he creatively utilized various calligraphic strokes to accommodate the pictorial models. The “brush spirit” (biyi 笔意) of not only old masters like Guo Xi but also ancient calligraphers flow within Zhao’s brush and hence imbues his painting with antique spirit. In addition, integration of the two art forms grants the brushwork the autonomy to exceed the constraint of creating representational forms but to mirror the artist’s mind. As early as in the Han Dynasty, Yang

Figure 23 (left). Zhao Mengfu, Twin Pines, Level Distance, detail of sapling branches. | Figure 24 (middle), Figure 25 (right). Zhao Mengfu, selections from Former Ode on the Red Cliff, 1301, album, ink on paper, 30.8 x 449.5 cm. National Palace Museum. | Figure 26. Guo Xi, Old Trees, Level Distance, detail of mountains. | Figure 27. Zhao Mengfu, Twin Pines, Level Distance, detail of mountains.

Xiong has written: “Handwriting, is the mind’s painting” [15]. The second canon of Xie He’s Six Laws states the “bone method” (gufa 骨法), which also emphasizes the link between handwriting and personality. Centuries later, Zhao reflected upon these ancient teachings by revolutionizing the function of painting. After him, landscape paintings need not be true to nature but should first and foremost express the artist’s selfhood. Wen Fong effectively denotes that “the difference between the Sung and Yuan landscape painters may be described as that between one who seeks nature and one who is nature”. [16]

In summary, Zhao Mengfu does not only inherit the legacies of old masters but passes them on in a renovated version that reflects his fully developed artistic theories, that is, instrumental archaism with the service of synthesizing calligraphy and painting. Casting away the highly aestheticized vision of the immediate past, Zhao actively searched to resuscitate the antique spirits. His formation of the canon is encapsulated by his Twin Pines, Level Distance. The history is not dead in this painting — the composition and semiotics derived from Guo Xi constitute the skeleton of the painting. But Zhao simplifies the motifs and fleshes them out with innovative incorporation of calligraphic brushworks as well as intimate inscriptions which explicitly reinforces his artistic ideals. Thus, Zhao’s artistry is never to be overlooked, but is rather buttressed by his success in making the past serve the present. A “mind’s painting” as his is, the minimalistic use of brush and ink does not incline to construct a welcoming landscape but outlines one that only Zhao himself can relate exclusively. What exactly is occupying his mind? What does it feel like for a royal descendent to serve the invaders? Zhao Mengfu leaves few surviving messages on this account. Nevertheless, though torn by his dual identities between the past and the present, he endures and survives like the straight pine trees. He gazes nostalgically into the hills beyond the river, where the distant history may enlighten a path for the future.

Endnotes

[1] James Cahill, Hills beyond a River: Chinese Painting of the Yüan Dynasty, 1279-1368, 1st ed, His A History of Later Chinese Painting, 1279-1950 ; v. 1 (New York: Weatherhill, 1976).

[2] Alfreda Murck, Poetry and Painting in Song China: The Subtle Art of Dissent, 1st ed., vol. 50 (Harvard University Asia Center, 2000), https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1dnn9rx.

[3] Ping Foong, ‘Guo Xi’s Intimate Landscapes’, in The Efficacious Landscape: On the Authorities of Painting at the Northern Song Court, Harvard East Asian Monographs 372 (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Asia Center, 2015).

[4] ‘Twin Pines, Level Distance’, The Met, n.d., https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/40508.

[5] Maxwell K. Hearn, ‘Painting and Calligraphy under the Mongols’, in The World of Khubilai Khan: Chinese Art in the Yuan Dynasty, ed. James C. Y. Watt (New York : New Haven [Conn.]: Metropolitan Museum of Art ; Yale University Press, 2010).

[6] ‘《元史 - 列传第五十九》’, 中国哲学书电子化计划, n.d., https://ctext.org/wiki.pl?if=gb&chapter=350758&remap=gb#p4. “以孟頫比唐李白、宋蘇子瞻。又嘗稱孟頫操履純正,博學多聞,書畫絕倫,旁通佛、老之旨,皆人所不及。”

[7] James Cahill, Hills beyond a River: Chinese Painting of the Yüan Dynasty, 1279-1368, 1st ed, His A History of Later Chinese Painting, 1279-1950 ; v. 1 (New York: Weatherhill, 1976).

[8] “《元史 - 列传第五十九》,” 中国哲学书电子化计划, n.d., https://ctext.org/wiki.pl?if=gb&chapter=350758&remap=gb#p4.

[9] Ping Foong, ‘Guo Xi’s Intimate Landscapes’, in The Efficacious Landscape: On the Authorities of Painting at the Northern Song Court, Harvard East Asian Monographs 372 (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Asia Center, 2015).

[10] MAXWELL K. HEARN, ‘SHIFTING PARADIGMS IN YUAN LITERATI ART: The Case of the Li-Guo Tradition’, Ars Orientalis 37 (2009): 78–106.

[11] Chu-Tsing Li, ‘Recent Studies on Zhao Mengfu’s Painting in China’, Artibus Asiae 53, no. 1/2 (1993): 195–210, https://doi.org/10.2307/3250514.

[12] Richard Vinograd, ‘“River Village: The Pleasures of Fishing” and Chao Meng-Fu’s Li-Kuo Style Landscapes’, Artibus Asiae 40, no. 2/3 (1978): 124–42, https://doi.org/10.2307/3249802.

[13] Wen Fong, Sung and Yuan Paintings (New York: distributed by New York Graphic Society, 1973).

[14] Foong, ‘Guo Xi’s Intimate Landscapes’.

[15] ‘《揚子法言 - 問神卷第五》’, 中國哲學書電子化計劃, n.d., https://ctext.org/yangzi-fayan/juan-wu/zhs?en=off. “书, 心画也。”

[16] Fong, Sung and Yuan Paintings.

Bibliography

Bush, Susan. The Chinese Literati on Painting. Hong Kong University Press, 2012. http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.wellesley.edu/stable/j.ctt2854hr.

Cahill, James. Hills beyond a River: Chinese Painting of the Yüan Dynasty, 1279-1368. 1st ed. His A History of Later Chinese Painting, 1279-1950 ; v. 1. New York: Weatherhill, 1976.

Fong, Wen. Sung and Yuan Paintings. New York: distributed by New York Graphic Society, 1973.

Foong, Ping. ‘Guo Xi’s Intimate Landscapes’. In The Efficacious Landscape: On the Authorities of Painting at the Northern Song Court. Harvard East Asian Monographs 372. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Asia Center, 2015.

Hearn, Maxwell K. ‘Painting and Calligraphy under the Mongols’. In The World of Khubilai Khan: Chinese Art in the Yuan Dynasty, edited by James C. Y. Watt. New York : New Haven [Conn.]: Metropolitan Museum of Art ; Yale University Press, 2010.

———. ‘Shifting Paradigms in Yuan Literati Art: The Case of the Li-Guo Tradition’. Ars Orientalis 37 (2009): 78–106.

Lee, Sherman E. Chinese Landscape Painting. New York: Harper & Row.

Li, Chu-Tsing. ‘Recent Studies on Zhao Mengfu’s Painting in China’. Artibus Asiae 53, no. 1/2 (1993): 195–210. https://doi.org/10.2307/3250514.

LI, CHU-TSING. ‘The Role of Wu-Hsing in Early Yüan Artistic Development Under Mongol Rule’. In China Under Mongol Rule, edited by John D. Langlois, 331–70. Princeton University Press, 1981. http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.wellesley.edu/stable/j.ctt7zv4pr.15.

Murck, Alfreda. Poetry and Painting in Song China: The Subtle Art of Dissent. 1st ed. Vol. 50. Harvard University Asia Center, 2000. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1dnn9rx.

‘Twin Pines, Level Distance’. The Met, n.d. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/40508.

中国哲学书电子化计划. ‘《元史 - 列传第五十九》’, n.d. https://ctext.org/wiki.pl?if=gb&chapter=350758&remap=gb#p4.

中國哲學書電子化計劃. ‘《揚子法言 - 問神卷第五》’, n.d. https://ctext.org/yangzi-fayan/juan-wu/zhs?en=off.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Zhi (Marina) Zhang is a rising senior double-majoring in Art History and Physics. Born and raised in a traditional Chinese family, she became deeply fascinated by ancient Chinese artistic cultures since she was a child. The author loves to explore the nuanced variances of the ink play and started to investigate the root causes hidden behind the brush strokes of ancient artists. Her favourite period in the long history of Chinese art is the Yuan Dynasty – a time when literati paintings began to flourish and gradually took central stage of Chinese literati culture. She is also interested in the interdisciplinary approach to art through the lens of cutting-edge technology.