“A Jew’s Daughter”: Metaphorical Bilingualism and the Tragedy of Religious Assimilation in The Merchant of Venice

To leave your religion is to destroy your entire upbringing—this is familiar advice from my fifth-generation Jewish American parents. Although the “Jewish bloodline” runs matrilineally[1] and my parents care less than previous generations about the religion of whom I marry, I know that if I were to convert, it could shatter my family. Perhaps this is why I sympathize with Jessica, from William Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice, and understand the gravity of her decision to marry a Christian and convert. The play centers on a Jewish moneylender, Shylock, who ultimately seeks a pound of flesh from the Merchant of Venice in order to repay a failed debt. His daughter, Jessica, converts later in the play to be with the Christian man she is in love with. Together, they run away to Belmont, the fictional land far from Venice where royal mishaps and chaos ensue. Religion ties strongly into identity, and in assimilating, parts of one’s soul can genuinely start to break. The changes she underwent following her conversion felt akin to the process of assimilation studied by linguists. While Jewish people were forced to assimilate following their expulsion from Spain in 1492,[2] a couple decades before Shakespeare’s life, I am not claiming that Shakespeare is making a commentary on religious conversion or about how Jews were forced to assimilate during his time. Instead, I am drawing a connection between how Jessica’s identity and relationships were damaged by her actions of conversion, similar to the consequences seen by bilingual families following American assimilation such as familial isolation and rejection of heritage. In this essay, I will explain Jewish identity, modern feelings towards conversion out of Judaism, and linguistic assimilation models in order to fully dive into the loss of self in Jessica’s conversion. Taking into account the perspectives of other scholars, an interview with my childhood Rabbi, and my own analysis of the play, the connections between bilingual assimilation and religious assimilation will further emphasize the true tragedy of Jessica’s conversion.

Gilbert Stuart Newton (1794-1835), Shylock and Jessica, From ‘The Merchant of Venice’, Act II, Scene II, 1830, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Fund

Judaism and Jewish Conversion

Before the significance of Jewish conversion can be understood, Judaism and its history of assimilation, as well as context as a religion, must first be fully explored. In an interview that I held with Rabbi Ilana Schwartzman in November 2024, she answers my question of what she defines being Jewish to be at its core: “I believe that Judaism is a buy into a certain social contact, that there are behaviors, expectations, and rules that we agree as a people that we agree we will or will not abide by.” Judaism has multiple layers aside from its religious duties, regarding tradition, history, and culture.[3]Although it has many similarities to other religions and many ways to practice, the key separating value is the belief in a messiah. If one believes that the messiah–-someone who will cure the world of its issues and bring goodness–-has come to Earth, they are instantly removed from the label of Judaism.[4] Even if one practices the religion and lives by Jewish values, the belief of the existence of a messiah is enough to no longer be considered Jewish. The Jewish family is of great importance, which can be seen by one of the ten commandments, a fundamental guide to morals in the religion, reading “Honor your father and your mother, so that you may live long in the land the Lord your God is giving you”.[5] Judaism is founded constantly on the personal basis of wanting to be Jewish. It is not because of how one was raised, or because they feel guilty if they are no longer practicing, but because they want to be a part of it.[6] Rabbi Schwartzman herself notes, “I’d like to think that I honor [my ancestor’s] memories by living a Jewish life, but that’s not my [sole] reason for being Jewish. Judaism is an identity practiced by millions of people worldwide, and built on the basis of shared history, culture, and religion in addition to ‘making Jewish choices’.”[7]

Jewish conversion has long been forced, a sacrifice with a complex history. Throughout history, Jews have faced numerous instances of exile, most recently in Nazi Germany, but also notably in the 1492 Spanish Inquisition.[8] Jews during the Middle Ages and later were forced to wear styles of clothing or badges that identified them as being Jewish, and this disdain of Jewish people would have still been maintained when Merchant was written.[9] In Shakespeare’s England, Jews were excluded from guilds based on being Jewish and generally were only able to be partially accepted when they were put in monetary roles.[10] Publicly declaring oneself as a convert, whether one truly converted or not, was a result of this exile and rampant antisemitism.[11] These conversos, or crypto-Jews, kept religion alive through the selection of certain aspects to practice and turn into religious memory.[12] Pre-1800s, conversion out of Judaism would have meant physically having to leave one’s family, as Jewish people were forced to live in ghettos—poor areas of towns where Jews were forced to live separated from Christians.[13] Familial feelings of betrayal when converting out of Judaism stems from centuries of exclusion, hate, and opposition. Because historically, much of Jewish suffering can be attributed to Christian power, many Jews feel that Christian conversion is succumbing to the oppressor. Marriage is relevant here, as it was seen dividing families to unite a new one. Over in the United States, intermarriage and/or intercourse between Jews and Christians were not legally prohibited until the 1870s, yet Jews were still actively villainized.[14] In this vein, Jews were able to be objectified, as it was legal to be intimate with Jewish people, but they were still subjected to hate speech and discrimination by the Christian majority. This likely came with the understanding that in marrying or procreating with a Jew, there was inherent conversion. Until 1862, many Jewish criminals were able to reduce their sentence if they underwent Christian baptism,[15] an ending eerily similar to Merchant’s Shylock. While the play does not overtly assign a motivation to Jessica’s conversion, I believe it to be a result from the social immobility that comes with being Jewish. She cannot be happy in this world if she is Jewish.

Even today, there is a specific betrayal in converting to Christianity as opposed to any other religion. I often joke with my own mother who reluctantly allowed my purchase of a small, colorful Christmas tree when I promised to call it a “Hanukkah bush” about the grievance from Jews towards Christmas. Many non-Jewish Americans still consider Hanukkah to simply be “the Jewish Christmas”, without taking time to learn about the holiday. Schwartzman brings up W. E. B. Du Bois’ theory regarding minorities and double consciousness, which says to be a minority means to know that the dominant culture does not need to know you.[16] In modern times, this same emphasis on comparison to gain understanding is applicable regarding my mention of the grievance that modern Jews may hold towards Christmas, as the holiday consistently gets compared to Christmas when the two holidays share nothing in common. Although they both mention miracles, Christmas celebrates the miraculous birth of Jesus Christ, whereas Hanukkah is a festival of lights and appreciation for the miracles that God grants. These holidays share very little similarities other than coincidental timing, yet Hanukkah is rarely ever fully understood. Shylock notes this in his infamous “I am a Jew speech” and compares Jewish people to Christians to gain sympathy and create any sense of understanding.

Fed with the

same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject to

the same diseases, healed by the same means,

warmed and cooled by the same winter and summer

as a Christian is? (3.1.59–63)[17]

The emphasis on Jewish families aggravates these feelings of betrayal in cases of conversion. Rabbi Schwartzman notes that when parents come sharing that their child has converted out of Judaism into another religion, there are two main sentiments. The first is feeling grief, betrayal, and questioning of where their parenting went wrong. The second is a relief that their child is still religious, but she emphasizes that she hears this statement far less. The combination of both historical prejudice against Jews from the Christian majority and the fact that Judaism is rarely understood when not in relation to Christianity makes modern Jewish conversion feel like absolute assimilation.

Washington Allston (1779-1843), Lorenzo and Jessica, 1832, Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Art Acquisition Endowment Fund

Bilingualism and the Assimilation Model

The core language of Judaism is Hebrew, the language that the Tanach is written in. Understanding the Hebrew language, although not prohibiting someone from being able to worship through text, allows one to fully comprehend the text.[18] Yiddish is a Germanic-language that utilizes Hebrew characters, and is one element of the Jewish American identity. From my own language perspective, a part of me has always resented the fact that my grandmother never taught my father Yiddish, who was then unable to pass the language onto me. The inability to speak a language so connected with my heritage eternally looms over me, as it does with many children that have fully assimilated into American culture and English. Linguists emphasize the importance of maintaining language in order to maintain familial connections. J.W. Berry’s Model of Acculturation notes that when immigrants come to America, they have one of four responses to learning English and adjusting to the new country: assimilation, integration, separation, and marginalization.[19] The two main responses are assimilation and integration, where assimilating involves rejecting the heritage culture in favor of incorporating “American” culture, while integration maintains the heritage culture alongside active participation in the American culture. The additional categories are separation, which maintains the heritage culture and entirely rejects the “American”, and marginalization, which typically occurs against an immigrant’s will and arises when they reject the heritage culture but struggle to adjust to American culture due to discrimination. It is posed that integration is the greatest outcome of the four significantly.[20] While many American nationalists pose the idea of a homogenous America, as seen in the melting pot metaphor, it inherently erases individual immigrant identities and encourages assimilation instead of integration.[21] Merchant’s Jessica falls into the assimilation category, as she rejects her Jewish identity to be a Christian. “O Lorenzo, if thou keep promise, I shall end this strife, become a Christian and thy loving wife” (2.4.19–21). This strife does not just refer to the pain from being apart, but that the only thing keeping them apart is her Jewishness. This point will be expanded later on but brings Jessica into the more harmful category of assimilation, in turn erasing a key aspect of her identity.

Raising children in an integrated household can hold many positive benefits and avoid the negative impacts of assimilation. Although it can be seen that raising a child as an integrated bilingual can have many positive effects, it is still incredibly common for a complete language shift to happen between two to three generations in America, where the heritage language is no longer spoken and entirely switches to English monolingualism.[22] This is seen often, for example, if immigrants speaking Italian raised their children in America as bilingual, but their children only used English due to the nature of the predominantly English-speaking school system, and by the time they were having children of their own they no longer used Italian whatsoever.[23] Within the three generations, the heritage language was lost completely, and the family had ultimately assimilated to English monolingualism. Yet, this is not to say that integration is impossible. Sarah Frances Phillips, a half Korean and half Black academic, reflects on her own language experience and the resistance of assimilation.[24] After numerous racist encounters, she declared to her mother that she no longer wanted to speak her heritage language, and after notes, “My relationship with my mom weakened when I stopped speaking Korean”.[25] She cites multiple studies, regarding the adverse effects that bilingual assimilation has on children including higher levels of stress, familial distance, and poor coping mechanisms later on in life. Speaking another language or at least having a small amount of understanding of it, is critical to strengthening an aspect of identity. Inverted Spanglish, coined by Jonathan Rosa, is used to create a shared Latinx identity, and shared ability to transform boundaries between English and Spanish within Latinx communities.[26] Inverted Spanglish is the opposite of Mock Spanish, and while Mock Spanish elevates whiteness and puts down the Spanish language, Inverted Spanglish shows proficiency in Spanish while also separating itself from whiteness.[27] Rosa found that even children across Latinx identities—in his study he discusses a Puerto Rican student and a Mexican student—can be bonded through the use of this Inverted Spanglish and creates solidarity.[28] Multiple communities are much more likely to be strengthened than weakened by integrating both heritage languages and English. In assimilating fully, aspects of one’s identity are lost.

Correlation Between Assimilation Models

Linguistic assimilation draws strong connections to religious assimilation. While language holds the ability to further connect with the ancient texts that Judaism is so strongly tied to, language has the greater power to unite other Jews with each other.[29] Yiddish was used during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century to connect Jews across Europe as they moved and underwent massive geographical changes,[30] likely either from leaving of free will or being forced out. Even in earlier times, Yiddish was used among Jews, even if they were from different regions, to find and connect with one another. Similar to the concept of Inverted Spanglish, although taking into account the intersectionality between racialization of Latinx Americans versus Jewish Americans, Yiddish or Hebrew can also be incorporated in English to establish a shared Jewish identity. When I am joking around with other Jewish friends, their mention of mashugana or chutzpah reminds me of our shared cultural understanding. Perhaps this is why “assimilation is a concern to all branches of American Jewry”.[31] The Religious Erosion-Assimilation Hypothesis notes that assimilation is most likely to occur when Jews are less religiously involved, observant, and surround themselves with people outside of Judaism.[32] Marrying outside of the religion and living in a predominantly Christian environment, as Jessica does in The Merchant of Venice, is likely to lead to assimilation according to this hypothesis. I think it is also important to note that assimilation is not necessarily always forced, although it is typically a product of the environment. Perhaps Jessica would not have converted had she not faced such strong antisemitism and could interact with other Jews, not just Christians. Similarly, perhaps American children that beg to be monolingual speakers would not have such a strong desire to abstain from their heritage language had they not faced or witnessed cases of discrimination, and bilingualism could be more accepted in this country.

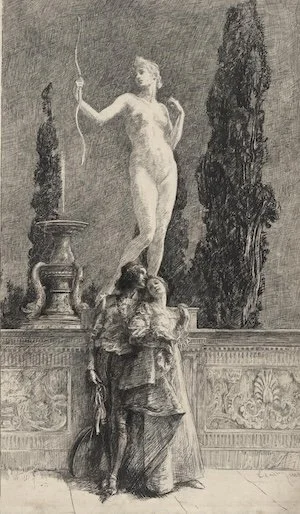

Edwin Austin Abbey (1852-1911), Lorenzo and Jessica: "The moon shines bright. In such a night as this" - Act V, Scene I, The Merchant of Venice, 1888, Edwin Austin Abbey Memorial Collection

Jessica: “A Jew’s Daughter”

In Shakespeare’s Merchant, the religious assimilation that occurred appeared to have similar adverse effects to bilingual assimilation. In both forms of assimilation, both the self and family are greatly impacted. Jessica rejects her culture in exchange for a life as Lorenzo’s wife. Jessica fully attempts to sever her Judaic connection in running away. She says, “Farewell, and if my fortune be not crossed, I have a father, you a daughter, lost” (2.5.57–58). As Phillips’s maternal relationship fractured when she rejected Korean, Shylock and Jessica’s relationship fractures when she rejects Judaism for Christianity. Jessica’s father is heartbroken when he discovers that Jessica has converted to marry a Christian:

SHYLOCK. I say that my daughter is to my flesh and blood

SALARINO. There is more difference between thy flesh and hers than between jet and ivory, more between your bloods than there is between red wine and Rhenish (3.1.37–41).

Adelman expands on this line by noting a patriarchal sense of belongingness and property that comes with this dated concept of marriage, “as though the transfer from father to husband could unbind her from her father’s blood after all”.[33] Because Jessica has married a Christian, it is almost as if she shares his religion, flesh, and blood with her husband as opposed to her father. It may be likely that Salarino wants to defend Jessica to mark a clear difference between Shylock and Jessica out of respect to his friend Lorenzo.[34] Salarino’s response shows how even non-Jews note the familial strain this leaving creates. After hearing the news towards the end of 3.1, Shylock breaks down, comparing the discussion of it to torture, “Thou torturest me” (3.1.119). However, just like in many cases of assimilation, Jessica is not entirely accepted. Lancelet tells Jessica, “Truly, then, I fear you are damned both by father and mother” referring to the fact that her Jewish parents have damned her (3.5.14–15). Scholars note that it is not just Jessica who is further isolated from her community following conversion. While Jessica is never truly accepted as a Christian, Shylock is also facing internal battles, referred to famously as “a faithless Jew”.[35] Jessica will always be “tainted” by her father’s Jewishness, and Shylock’s Jewishness will always be “tainted” by the fact that his daughter chose to marry a Christian.[36] Characters in the play do not hesitate to let her know this, especially Launcelot:

He tells me flatly that there’s no mercy for

me in heaven because I am a Jew’s daughter; and

he says you [Lorenzo] are no good member of the commonwealth,

for in converting Jews to Christians you

raise the price of pork (3.5.31–35).

Aside from the problematic comparison of conversion to meat prices rising, it is clear that many people disapprove of Jessica’s conversion. Jessica wonders “alack, what heinous sin is it in me to be ashamed to be my father’s child?” (2.3.16–17). Jessica’s assimilation in marrying Lorenzo and converting to Christianity still marginalizes her and therefore draws connections to the linguistic marginalization as seen in Berry’s model—rejection from both heritage speakers and native English speakers, similar to her rejection from both Jewish communities as well as Christian communities. Jessica’s willingness to sacrifice her culture and Lorenzo’s unwillingness to embrace hers forms a crack in their relationship. In 5.1, the audience sees her growing distaste towards her husband in the ring scene as they exchange metaphorical punches. Similarly, children raised without connection to their heritage language often feel disdain towards the culture itself. But as bilingual children grow up, they regret this and revert to speaking mainly in the minority language.[37] This phenomenon is the most tragic because it is a choice they are forced to make as a result of this marginalization.

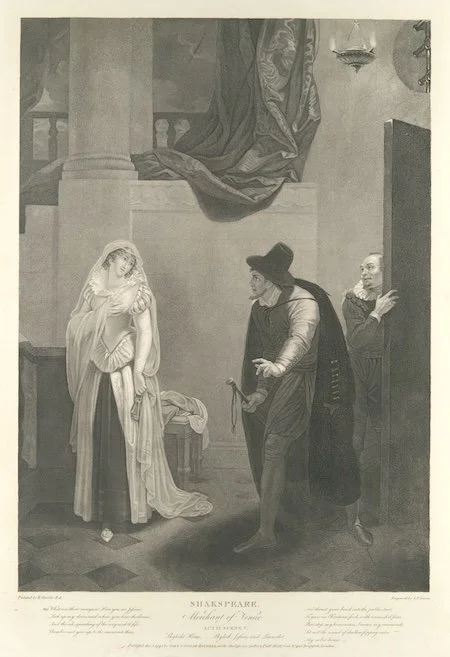

Peter Simon (1764-1813) and After Robert Smirke (1752/53-1845), Shylock's House–Shylock, Jessica and Launcelot (Shakespeare, Merchant of Venice, Act 2, Scene 5), 1795, reissued 1852, The Met Museum, Gertrude and Thomas Jefferson Mumford Collection, Gift of Dorothy Quick Mayer, 1942

The Merchant of Venice poses many dichotomies that the world follows. The play hinges on the association of the majority with goodness and inspiration, see characters like Antonio or Portia, while characters in the minority are written antagonistically, such as The Prince of Morocco or Shylock. Jews are held to a degree of gentility that they must be accountable for,[38] while missteps are more excusable for Christians as seen in 4.1’s trial scene. Objectively, it is Antonio that has failed but Shylock is accused of being the immoral one. Regarding Jessica, Coodin argues that she desperately wants to be a part of this Christian community and assimilate and does so in marrying Lorenzo.[39] She does not choose to marry him and remain true to her Jewish faith or even attempt to somehow observe both religions, instead adhering to the black-and-white dichotomy that is formed—Jewish or Christian. Even Shylock and Jessica are pit against each other in a way as the nefarious Jewish father and the desirable Jew that converted. It becomes interesting to look at how these characters are both shown in contemporary productions as individuals. In modern works, Jessica is villainized in order to have the audience sympathize with Shylock to refrain from the antisemitic criticisms that inherently come with reproducing this play, while in different productions the Judaic “otherness” is emphasized.[40] In some theatrical productions, Shylock’s Jewishness is overemphasized, as he is seen wearing a kippah to immediately draw his connection as not only a Jew but as certainly not a Christian. In some others, productions are careful not to have her exhibit any “Christian” traits until her conversion, instead of showing her reject “Jewish” traits.[41] These differences in the portrayal of Jessica versus Shylock may explain the criticism Jessica faces, who vehemently agree that her conversion is a betrayal.[42] By establishing a dichotomy within current productions, the religious assimilation becomes painfully obvious.

Metaphorical Bilingualism and Religious Assimilation

Jessica’s coerced assimilation follows similar pathways to children that assimilate from their heritage culture to an American one. Both linguists and contemporary audiences of The Merchant of Venice hope that Jessica chooses to return to her Jewish culture after the play ends. By drawing connections between Jessica and Shylock’s forced assimilation as a metaphor for bilingual assimilation, we are reminded of the real struggles that American immigrants face: the loss of language and loss of generational identity. In conclusion, I’d like to argue that the realism of this situation makes it all so heartbreaking. In my own experience as a Jewish daughter, I know that there would be detriment to my familial relationships and my own values if I were to marry someone that was unaccepting of my culture or wanted to raise our children non-Jewish. My parents would not have a problem with marrying outside of the Jewish religion, but if I were to convert or baptize my children one day, I know that would shatter them. In converting, Jessica lost touch with not just her father and her husband’s community, but most heartbreakingly with herself. She will never be Jewish enough for the Jews, nor Christian enough for the Christians. She is eternally stuck in a desolate middle ground. Through assimilating, she has lost touch with her religion, her culture, and her family all for a relationship that she does not appear to be happy in at the play’s close. Her sacrifice was almost “worth it” to be included, to escape discrimination, to live a wealthy life. But at the end of the day, she is and will always be regarded as “a Jew’s daughter” (3.5.32) in Shakespeare’s world.

Endnotes

[1] Sara Coodin, “Stolen Daughters and Stolen Idols,” in Is Shylock Jewish?, Citing Scripture and the Moral Agency of Shakespeare’s Jews (Edinburgh University Press, 2017), 156, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3366/j.ctt1pwt2f2.9.

[2] Ilana Schwartzman, FaceTime with the Author, November 15, 2024.

[3] Schwartzman, interview. See https://www.jstor.org/stable/23605999 or Anita Diamant and Howard Cooper’s Living a Jewish Life: Jewish Traditions, Customs, and Values for Today’s Families (2007) for furthered reading.

[4] Schwartzman, interview. See https://www.researchgate.net/publication/309484255_Jesus_for_Jews_The_Unique_Problem_of_Messianic_Judaism Zev Garber and Kenneth L. Hanson’s Judaism and Jesus (2019) for furthered reading.

[5] Exod. 20:12

[6] Schwartzman, interview.

[7] Anita Diamant and Howard Cooper, “Preface,” in Living a Jewish Life: Jewish Traditions, Customs, and Values for Today’s Families, Updated and rev. ed (New York, NY: HarperCollins, 2007): 7.

[8] Schwartzman, interview.

[9] Janet Adelman, “Her Father’s Blood: Race, Conversion, and Nation in The Merchant of Venice,” Representations 81, no. 1 (February 1, 2003): 10, https://doi.org/10.1525/rep.2003.81.1.4.

[10] Schwartzman, interview.

[11] Hilda Nissimi, “Religious Conversion, Covert Defiance and Social Identity: A Comparative View,” Numen 51, no. 4 (2004): 377.

[12] Nissimi, “Religious Conversion, Covert Defiance and Social Identity,” 396.

[13] Schwartzman, interview.

[14] Todd M. Endelman, “Neither Jew nor Christian: New Religions, New Creeds,” in Leaving the Jewish Fold: Conversion and Radical Assimilation in Modern Jewish History (Princeton University Press, 2015), 89–90, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv7h0tfc.

[15] Endelman, “Neither Jew nor Christian: New Religions, New Creeds,” 99.

[16] Schwartzman, interview.

[17] Shakespeare, William. The Merchant of Venice. (Folger Shakespeare Library. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2004)

[18] Schwartzman, interview.

[19] John W. Berry, “Acculturation: Living Successfully in Two Cultures,” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 29, no. 6 (November 2005): 697, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2005.07.013.

[20] Berry, “Acculturation,” 697.

[21] Susan Tamasi and Lamont Antieau, “Multilingual America,” in Language and Linguistic Diversity in the US (Routledge, 2014), 189.

[22] Tamasi and Antieau, “Multilingual America,” 196.

[23] Tamasi and Antieau, “Multilingual America,” 196.

[24] Sarah Frances Phillips, “What We Lose When We Don’t Speak the Same Language as Our Immigrant Parents” Joy Sauce, May 18, 2022,https://joysauce.com/asian-american-identity-bilingualism-assimilation/.

[25] Phillips, “What We Lose When We Don’t Speak the Same Language as Our Immigrant Parents.”

[26] Rosa, Jonathan, “From Mock Spanish to Inverted Spanglish: Language Ideologies and the Racialization of Mexican and Puerto Rican Youth in the United States”, in Raciolinguistics: How Language Shapes Our Ideas About Race (2016) https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190625696.003.0004

[27] Rosa, Jonathan, “Mock Spanish.”

[28] Rosa, Jonathan, “Mock Spanish.”

[29] Schwartzman, interview.

[30] Coodin, “Stolen Daughters and Stolen Idols,” 201.

[31] Jerome S. Legge, “The Religious Erosion-Assimilation Hypothesis: The Case of U.S. Jewish Immigrants,” Social Science Quarterly 78, no. 2 (1997): 484. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42864349

[32] Legge, “The Religious Erosion-Assimilation Hypothesis,” 475.

[33] Adelman, “Her Father’s Blood,” 13.

[34] Adelman, “Her Father’s Blood,” 13.

[35] Lara Bovilsky, “‘A Gentle and No Jew’: Jessica, Portia, and Jewish Identity,” Renaissance Drama 38 (2010): 56. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41917470

[36] Bovilsky, “A Gentle and No Jew,” 56.

[37] Tamasi and Antieau, “Multilingual America,” 196.

[38] Bovilsky, “A Gentle and No Jew,” 57.

[39] Coodin, “Stolen Daughters and Stolen Idols,” 172.

[40] Irene Middleton, “A Jew’s Daughter and a Christian’s Wife: Performing Jessica’s Multiplicity in The Merchant of Venice,” Shakespeare Bulletin 33, no. 2 (2015): 296. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26355110

[41] Middleton, “A Jew’s Daughter and a Christian’s Wife,” 298.

[42] Camille Slights, “In Defense of Jessica: The Runaway Daughter in The Merchant of Venice,” Shakespeare Quarterly 31, no. 3 (1980): 357, https://doi.org/10.2307/2869199.

Sarah Cassell

Sarah Cassell is a rising junior at Emory University, majoring in Art History with a minor in English Rhetoric, Writing, and Information Design. She adores arts and writing, going on to become the founding Editor-in-Chief of the on-campus editorial fashion magazine, Eternal Magazine, now with hundreds of contributors. As she grows as an academic, Sarah is especially interested in the religious and gender intersections of artwork, media, and literature.