Aristotle Visits Bed-Stuy: The Practical Wisdom and Rhetorical Virtue of Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing

“Are we gonna live together? Together are we gonna live?” asks radio DJ Mister Señor Love Daddy—played by Samuel L. Jackson—at the conclusion of Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing.[1] Facing this question about racial conflict is inevitable after watching Lee’s 1989 film, which traces the rising racial tension of one summer day in Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood. Since its debut, Do the Right Thing has centered itself as a quintessential piece of cinema regarding the issue of American race relations; it is also considered one of the greatest films ever made. Lee himself portrays the main character, Mookie, an African American father working at an Italian-owned pizzeria in Brooklyn who must engage the racial conflict surrounding that restaurant. Throughout the multi-layered picture, Lee consults several viewpoints on the matter—including the ideologies of Martin Luther King Jr. (1929–1968) and Malcolm X (1925–1965)—in how to address racial injustice and marginalization, challenging what “the right thing to do” exactly is. To develop authenticity and his overall message, Lee relies heavily on Aristotelian rhetoric, of which rhetorical virtue and practical wisdom stand out.

Wes Candela, SLAM Cinema: Do the Right Thing, 2008-2017, photography, Saint Louis Art Museum, https://www.slam.org/event/slam-cinema-do-the-right-thing/

The film is considered a masterpiece both through Lee’s skills as a filmmaker and the enduring legacy of its messaging. Not only does it genuinely portray African Americans in a considerate and honest fashion, but also its uncensored portrayal of the conflict between Blacks and whites extends the film to a broad audience. Acclaimed film critic Roger Ebert placed Do the Right Thing on his “Great Movies” list of the best pictures to grace the silver screen. Ebert praises Lee’s ability to offer an objective, empathetic look into racial strife: “Spike Lee had done an almost impossible thing. He’d made a movie about race in America that empathized with all the participants. He didn’t draw lines or take sides but simply looked with sadness at one racial flashpoint that stood for many others.”[2] By analyzing Lee’s utilization of rhetoric, one can understand Do the Right Thing’s ability to give a voice to the marginalized and its deeper layers as a cinematic classic.

Alex Oliveira, Spike Lee Peabody Awards 2011, 2011, photography, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=28809754

The film follows Mookie and an assortment of characters in the demographically diverse Brooklyn neighborhood of Bedford-Stuyvesant. On a sweltering summer day, racial tensions escalate between the community members, with the focal struggle being between Mookie’s Italian American employer Sal, his family, and two African Americans: Buggin’ Out and Radio Raheem. Do the Right Thing is episodic in nature, as it depicts multiple loosely connected storylines that gradually converge into a climactic tragedy.

Do the Right Thing is now thirty-five years in age, but the messages are just as relevant today. The New Yorker film critic Richard Brody emphasized this point when reflecting on the death of George Floyd (1973–2020): “‘Do the Right Thing’ is, regrettably, not a work of history but a film set, in many ways, in the present tense.”[3] As America still resides in racial turmoil, the development of media that reaches and impacts a wider racial audience, as Lee was able to create, may be more needed than ever. Putting the rhetorical scope upon this late twentieth century classic can help decipher the film’s deeply pertinent messages, and its analysis can inform further positive developments in racial discourse and media.

At its core, Do the Right Thing asks a rather obvious moral question: What is the right thing to do regarding racial struggle? Considering ethics and character—which align directly with this posed question—the concept of ethos is likely the most salient idea in rhetorical theory. Specifically, two of its major components apply directly to how Lee constructed this iconic film: practical wisdom (phronesis) and rhetorical virtue (arete). I will argue that Spike Lee utilizes practical wisdom and rhetorical virtue in Do the Right Thing to convey an unbiased glimpse into American racial tension and to offer a more complex ideology on how to address race-related conflicts.

The components of this rhetorical framework stem from Aristotle’s conception of rhetoric. According to philosopher Amélie Rorty, these components are crucial in developing a persuasive message and ascribing moral uprightness to the rhetor: “As Aristotle puts it, virtue involves doing the right thing at the right time, in the right way and for the right reason. Speaking persuasively—rightly and reasonably saying the right things in the right way at the right time—is a central part of acting rightly.”[4] Cultivating these aspects of ethos in one’s message is critical to the audience’s understanding of the speaker as a credible figure—both in subject matter and as a person in general. Practical wisdom, as author Jay Heinrichs posits, results in the audience considering the speaker “a sensible person, as well as sufficiently knowledgeable to deal with the problem at hand. In other words, they believe you know your particular craft.”[5] A practically wise person gives the impression that they truly know the issue they are addressing and can offer an accurate answer. Rorty reflects on this idea about the phronimos (practically wise person): “His desires—the desires that prompt and direct his use of rhetoric—are (in)formed by true understanding; and his understanding of the issues at stake in persuasion is formed by appropriately formed desires.”[6] In doing so, the persuader takes upon the appearance of wisdom and credibility.

Nick Thomas, Aristotle, April 23, 2011, photograph, flicker, https://www.flickr.com/photos/pelegrino/6884873348

Embodying rhetorical virtue, however, means that the speaker takes upon the appearance of virtue and upright character. This component, as Heinrichs notes, involves “more adaptation than righteousness. You adapt to the values of your audience.”[7] According to scholars James S. Baumlin and Craig A. Meyer, rhetorical virtue ultimately stems from ethos lying between the audience and speaker: “[B]elonging to neither wholly, the rhetor’s ethos is built out of a speaker-audience interaction.”[8] As a result, being seen as morally upright derives from the audience’s values and their perception of the speaker. Furthermore, by adapting one’s message to embody the values of multiple groups, a rhetorician can build a stronger polyphonic argument that appeals to a wider audience.

Spike Lee capitalizes on the two rhetorical concepts in his crafting of Do the Right Thing. The story tracks a day in the life of Mookie, played by Lee, a resident of Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood—colloquially called “Bed-Stuy.” He lives with his sister Jade, working at a pizzeria to provide for his son, Hector, and girlfriend, Tina. The pizzeria is operated by Italian American Salvatore “Sal” Frangione, who prides himself on having fed the kids of the area for over twenty years, and his two sons, Pino and Vito. Lee introduces the audience to a medley of characters, including the kindly local drunk Da Mayor, the matriarchal Mother Sister, the boombox-toting Radio Raheem, the frustrated Buggin’ Out, the mentally challenged Smiley, and the aforementioned DJ Mister Señor Love Daddy, who serves as a side narrator of the day’s events. Lee also portrays the struggles of local Puerto Ricans, young African Americans, and an Asian American family that operates a convenience store. The neighborhood is heavily monitored by local police, creating continuous tension between the Bed-Stuy’s residents and law enforcement.

Matthew Rutledge, Bed-Stuy brownstones, June 25, 2005, photography, https://www.flickr.com/photos/rutlo/

Over the course of one brutally hot summer day, tensions rise between tenants in the neighborhood. Hostility is abundant; such struggles include Mookie’s relationship with Tina and Pino, young Blacks arguing with the older Da Mayor, and Pino against his own father. The major struggle, however, occurs from Buggin’ Out’s anger that Sal’s Pizzeria, despite being in a predominantly Black neighborhood, holds only Italian American figures on its “Wall of Fame.” Due to Sal’s negative response toward his frustration, Buggin’ Out orchestrates a boycott with Radio Raheem, an imposing young man who struts around Bed-Stuy perpetually playing Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power” on his boombox. In a devastating confrontation, Sal ends up destroying Radio Raheem’s boombox, causing a fight that takes the conflict into the streets of Bed-Stuy. In the immense chaos of the fight, cops arrive and tragically choke Radio Raheem to death and arrest Buggin’ Out. In the face of Raheem’s murder, Mookie throws a garbage can through the window of Sal’s pizzeria, causing a mob of neighborhood residents to destroy the restaurant. The next day, Mookie meets Sal outside the ruins of the twenty-five-year-old establishment. Although Sal is bitter, the two reconcile as Mookie receives his final payment. At the film’s conclusion, Lee showcases two quoted messages. The first comes from Martin Luther King, Jr. advocating nonviolence:

Violence as a way of achieving racial justice is both impractical and immoral. It is impractical because it is a descending spiral ending in destruction for all. The old law of an eye for an eye leaves everybody blind. It is immoral because it seeks to humiliate the opponent rather than win his understanding; it seeks to annihilate rather than to convert. Violence is immoral because it thrives on hatred rather than love. It destroys community and makes brotherhood impossible. It leaves society in monologue rather than dialogue. Violence ends by defeating itself. It creates bitterness in the survivors and brutality in the destroyers.[9]

The second comes from Malcolm X advocating for self-defense:

I think there are plenty of good people in America, but there are also plenty of bad people in America and the bad ones are the ones who seem to have all the power and be in these positions to block things that you and I need. Because this is the situation, you and I have to preserve the right to do what is necessary to bring an end to that situation, and it doesn’t mean that I advocate violence, but at the same time I am not against using violence in self-defense. I don’t even call it violence when it’s self-defense, I call it intelligence.[10]

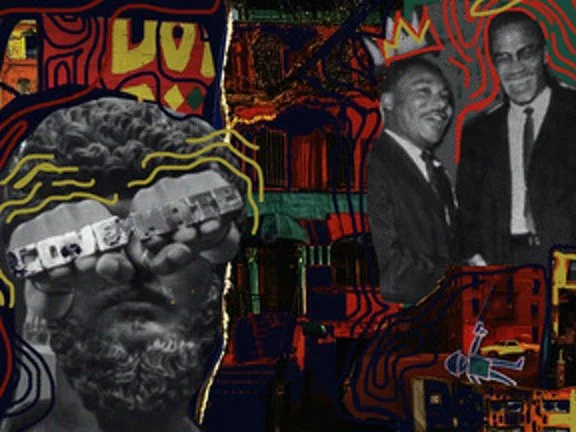

This is followed by an image of the two shaking hands (a picture that Smiley carried throughout the film) and a dedication to six victims of racial violence and police brutality.

Dick DeMarsico, Gracie Mansion, Rev. Martin Luther King press conference / World Telegram & Sun photo by Dick DeMarsico, July 30, 1964, photographic print, https://www.loc.gov/item/99404328/

As displayed in Do the Right Thing, Lee exhibits phronesis in two discrete ways: his choice in portraying the main protagonist and his pronounced skill as a filmmaker. Filmmakers rely on ethos in order bring their audience into the reality of the narrative they construct. Scholar Laurence Behrens articulates the importance of ethos in cinema when he writes, “The filmmaker has to convince us not only that his heart and his mind are in the right place, but also that he knows how to handle his material, that he is aware of our expectations, and can skillfully respond to them.”[11] Regarding the significance of ethos, Lee must communicate to his audience that he understands the issue of racial turmoil; he does this by inserting himself directly within the film’s conflict. This decision gives Lee a distinctive edge as the film’s storyteller. Throughout the film, Mookie is continuously received as a figure of respect both from Blacks in his community and from the white figure of Sal; the pizzeria owner even considers Mookie like a son: “[T]here will always be a place for you at Sal’s Famous Pizzeria.”[12] Even so, Mookie remains a deeply human character: he is a flawed father, who is often absent from Tina and Hector, and slacks around at work. Through these flaws, however, Lee paints Mookie as a person who knows the harsh reality of being a member of a marginalized community—as a human being who is trying to figure life out too. Mookie also acts as an intermediary figure between both white and Black communities; his job in pizza delivery depends on him to meet the demands of his white boss and Black clientele. As film historian James C. McKelly writes, Mookie traverses between both white and Black worldviews, which is symbolically reflected in Mookie’s apparel: “The Brooklyn Dodgers jersey Mookie wears on his way to work in the morning—Jackie Robinson’s #42—suggests, as Nelson George puts it, that ‘he’s a man watched closely by interested parties on both sides of the racial divide. Both sides think he’s loyal to them.’”[13] In the process, Mookie gives Lee an air of practical wisdom as one who can handle both white and Black forms of discourse—a person respected by both communities. In sum, Lee’s role cultivates the director’s phronesis by portraying him as a struggling, flawed person respected by both Black and white communities, as well as a person who can act as a catalyst for positive change.

Lee’s capabilities as a director also convey practical wisdom. Behrens asserts the importance of the film auteur’s introductory section of the film—otherwise called the exordium. By immediately showing their skill as a storyteller, this first impression is crucial for seizing the audience’s attention.[14] Lee’s exordium, in this light, excels as Do the Right Thing opens with an extended dance sequence of Tina—played by Rosie Perez—set to the tune of Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power.” Cultural historian Thomas Doherty elaborates on Lee’s cinematic genius in this opening: “Dreamy pull backs, long takes, and off-kilter close-ups (Lee calls them ‘Chinese angles’ after the awed, skewed gaze of the kung fu films) define the directorial style; the color scheme is a steamy yellow and dull red, a cinematographic slow burn conjuring the equatorial oppression of summer in the city.”[15] As Doherty posits, the non-diegetic scene showcases impeccable choreography, energetic usage of the camera, and an elaborate display of colors; the color contrasts reflect the motif of duality within the film, seen later with the contrasting ideologies of King and Malcolm X. This elaborate exordium shows, without a doubt, that Lee knows his craft well.

Throughout the rest of the film, Lee continues to display his directorial ability. He utilizes a myriad of camera angles to illuminate qualities of certain characters. One such instance is when a white Celtics fan living in Bed-Stuy accidentally scuffs Buggin’ Out’s Air Jordan sneakers. Lee gives a tight close-up of Buggin’ Out, lucidly conveying the character’s sense of exasperation. Doherty writes that this moment is “a sidewalk vignette accessible only to the kind of director who still personally scouts his locations on bicycle. He remains as fluent in street patois as film grammar.”[16] In this moment, Lee conveys not only his craft as a filmmaker but also as an individual that knows the inner workings of the “streets.” Another instance of excellent film composition occurs when Mookie is expressing his concern about Sal’s attraction to Jade. As Mookie and Jade argue about the situation next to the pizzeria, the audience can see behind them scrawled in graffiti “Tawana Told the Truth.”[17] The graffiti alludes to the accusations of rape made by African American woman Tawana Brawley against four white men.[18] Despite support from the Black community and the fact that she had been brutalized, all accusations were discarded in court. In this detail, Lee conveys his knowledge about Black frustration regarding injustice, using it to inform the thought processes of his characters. Continuous details such as these in Do the Right Thing convey Lee as a brilliant filmmaker deeply informed about the plight of the marginalized.

Laure Wayaffe, Buggin Out, 2008, https://www.flickr.com/photos/22634122@N05/2551422679

To continue building the ethos of himself and the film, Lee makes Do the Right Thing rhetorically virtuous by portraying its litany of characters in a sympathetic, unbiased light; thus, he creates a polyphonic film that represents the values of many people. The struggle between Buggin’ Out and Sal about the “Wall of Fame,” for instance, portrays each character objectively in their positions. Scholar Colette Lindroth illuminates their conflict well:

Buggin’ Out has a reasonable request, which he communicates with unreasonable force; Sal has a reasonable reservation, which he communicates with contemptuous dismissal. No one is entirely wrong here….Sal is right in feeling free to put his own heroes in his own walls; Buggin’ Out is right in feeling that, in a Black community, a Black face or two among those heroes isn’t too much to ask. Unfortunately, feelings, instead of reason, speak.[19]

By making this tension the epicenter of the film, Lee embodies the values of audience members who side with Sal or Buggin’ Out. In doing so, he displays the conflict objectively, in all its strengths and flaws.

Lee tackles moral dualism—thus appealing to audience members who subscribe to this understanding—through the character of Radio Raheem. Raheem, defined by his boombox that blares “Fight the Power,” is likely best remembered for his LOVE-HATE monologue. On brass knuckle rings—"LOVE” on the right hand and “HATE” on the left—Raheem performs for Mookie the eternal battle between these two concepts in a manner that echoes the evil preacher of Charles Laughton’s film, Night of the Hunter:

Let me tell you the story of Right Hand, Left Hand—the tale of Good and Evil….The story of Life is this: STATIC! One hand is always fighting the other. Left Hand is kicking much ass. I mean, it looks like Right Hand, Love, is finished. But hold on, stop the presses, the Right Hand is coming back! Yeah, he got the left hand on the ropes, now that’s right. Ooh, it’s a devastating right and Hate is hurt, he’s down. Left-Hand Hate KO’ed by Love.[20]

Embodying the value of moral dualism, Raheem offers a compelling narrative: “In it, ‘good’ is not only identifiable and absolute, but ultimately more powerful than ‘evil,’ which correspondingly, is equally pure and clear.”[21] In this iconic monologue, Lee appeals to those who value moral dualism. However, through Raheem’s involvement in the confrontation at the pizzeria and his tragic death, Lee offers a critique of this thought pattern concerning racial turmoil. Although easy to classify, Lee suggests that a proper solution to such matters might be more morally gray and nuanced than moral dualism.

Do the Right Thing’s character Smiley addresses those who value the ideologies of King or X. The mentally challenged Smiley bears an image of King and X shaking hands with one another. He accosts people to buy his pictures and listen to their ideologies. King’s liberal integrationist view emphasizes nonviolence as the means for racial progress: “It is no longer a choice between violence and nonviolence in this world; it’s nonviolence or nonexistence.”[22] As a Black Nationalist, X advocates for self-defense, even violence, as a means of protection: “I don’t even call it violence when it’s self-defense, I call it intelligence.”[23] Through Smiley, both thought patterns are represented, showcasing Lee’s exhibition of rhetorical virtue. Even so, Lee critiques the dualism of their ideologies by rendering Smiley unheard: “His incoherence, however, coupled with his insistence, turns people off instead of involving them. Ironically, none of these Black Americans want to hear much about Martin or Malcolm on this hot summer day.”[24] Rather ingeniously, Lee entreats both ideologies—utilizing rhetorical virtue—and rebukes their contrasting nature. This points to Lee’s ultimate message in Do the Right Thing, which is embodied through Mookie’s climactic act.

Mookie, in addition to illuminating Lee’s phronesis, is also the film’s most rhetorically virtuous character. Throughout the film, Mookie is told a variety of conflicting messages: “From Buggin’ Out, he hears, ‘Stay black’; from Mother Sister, ‘Don’t work too hard today’…from his wife Tina, ‘Be a man’; from Sal, ‘You’re fuckin’ up’; and from Da Mayor, the clincher of this paradoxical parade of morally absolutist signification: ‘Always try to do the right thing.’” [25] As a result, Mookie’s character reflects countless values of the audience, many of which are incompatible. However, in his act of initiating the destruction of the pizzeria via the garbage can, Mookie points to a new form of ideology that supersedes the dualism of good against evil and King against X. As scholar W. J.T. Mitchell articulates, the film “resituates both violence and nonviolence as strategies within a struggle that is simply an ineradicable fact of American public life.”[26] For Lee, “fixing” racial conflict should not be a morally absolutist endeavor. The film ends with the image of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr. shaking hands. This image advocates for a nuanced, unified ideology that dares to tread the moral grayness of racial strife. Lee wrote in his journal about the film, “In the end, justice will prevail, one way or another. There are two paths to that. The way of King, or the way of Malcolm.”[27] This flexible ideology sees justice within both camps, and “doing the right thing” might mean going down one of these paths over another in differing circumstances.

Through phronesis and arete, Lee creates a remarkable ethos about himself and Do the Right Thing in a manner that needs replication in modern communication. Lee builds himself up as a voice worthy of contributing to the discussion of racial struggle; he does this by showcasing his talents as a filmmaker as well as being an informed person. More importantly, he develops an incredibly polyphonic film that embodies the myriad values the audience may hold. In doing so, he reaches a remarkably wide audience, holds their attention, and imposes thoughtful criticism upon them. His nuanced ideology about racial struggle, emphasizing the importance of both King and X, sharply critiques the moral absolutism that perseveres to this day regarding race relations. This is why Lee’s film has such an enduring legacy. For whatever issue that needs to be addressed—especially racial turmoil—communicators must display craft and rhetorical virtue in their messages. Much of today’s media landscape is poorly conducted, underinformed, and incredibly biased. To foster enduring films like Do the Right Thing, communicators must strive for this aura of ethos that Lee attains with practical wisdom and polyphonic messaging.

Spike Lee’s rhetorical usage of phronesis and arete allows him to convey an objective glimpse into racial turmoil through the microcosm of Bed-Stuy; he also develops a more nuanced ideology on how to address such tension. Ebert reflects on this achievement, saying that Do the Right Thing “doesn’t ask its audiences to choose sides; it is scrupulously fair to both sides, in a story where it is our society itself that is not fair.”[28] As Do the Right Thing continues to be acclaimed and remain pertinent to current affairs, modern forms of communication must be challenged to strive for the same. By building proper ethos, current communicators can create impactful messages like Lee’s. To conclude with the words of Mister Señor Love Daddy, current communicators need to do one thing regarding practical wisdom and rhetorical virtue: “Wake up!”[29]

Spike Lee’s rhetorical usage of phronesis and arete allows him to convey an objective glimpse into racial turmoil through the microcosm of Bed-Stuy; he also develops a more nuanced ideology on how to address such tension. Ebert reflects on this achievement, saying that Do the Right Thing “doesn’t ask its audiences to choose sides; it is scrupulously fair to both sides, in a story where it is our society itself that is not fair.”[28] As Do the Right Thing continues to be acclaimed and remain pertinent to current affairs, modern forms of communication must be challenged to strive for the same. By building proper ethos, current communicators can create impactful messages like Lee’s. To conclude with the words of Mister Señor Love Daddy, current communicators need to do one thing regarding practical wisdom and rhetorical virtue: “Wake up!”[29]

Kristen Baurain, Street Ethos, 2025, digital collage made with Adobe Photoshop.

Endnotes

[1] Do the Right Thing, directed by Spike Lee (1989; Universal City, CA: Universal Pictures Home Entertainment, 2012), DVD.

[2] Roger Ebert, “Great Movie: Do the Right Thing,” rogerebert.com, May 27, 2001, https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/great-movie-do-the-right-thing-1989.

[3] Richard Brody, “The Enduring Urgency of Spike Lee’s ‘Do the Right Thing’ at Thirty,” The New Yorker, June 28, 2019, https://www.newyorker.com/culture/the-front-row/the-enduring-urgency-of-spike-lees-do-the-right-thing-at-thirty.

[4] Amélie Rorty, “Aristotle on the Virtues of Rhetoric,” The Review of Metaphysics 64, no. 4 (2011): 715.

[5] Jay Heinrichs, Thank You for Arguing (New York: Broadway Books, 2020), 68.

[6] Rorty, “Aristotle,” 716.

[7] Heinrichs, Thank You, 65.

[8] James S. Baumlin and Craig A. Meyer, “Positioning Ethos in/for the Twenty-First Century: An Introduction to Histories of Ethos,” in Histories of Ethos: World Perspectives on Rhetoric, ed. James S. Baumlin and Craig A. Meyer (Basel: MDPI-Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute, 2022), 10.

[9] Lee, Do the Right Thing.

[10] Lee, Do the Right Thing.

[11] Laurence Behrens, “The Argument in Film: Applying Rhetorical Theory to Film Criticism,” Journal of the University Film Association 31, no. 3 (1979): 8.

[12] Lee, Do the Right Thing.

[13] James C. McKelly, “The Double Truth, Ruth: Do the Right Thing and the Culture of Ambiguity,” African American Review 32, no. 2 (1998): 220.

[14] Behrens, “Argument in Film,” 8.

[15]Thomas Doherty, Film Quarterly 43, no. 2 (1989): 37, https://doi.org/10.2307/1212807.

[16] Ibid, 37.

[17] Lee, Do the Right Thing.

[18] Gene Demby, “The Racial Backdrop of the Tawana Brawley Case,” NPR, August 5, 2013, https://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2013/08/05/209254781/the-racial-backdrop-of-the-tawana-brawley-case.

[19] Colette Lindroth, “Spike Lee and the American Tradition,” Literature Film Quarterly 24, no. 1 (1996): 28.

[20] Lee, Do the Right Thing.

[21] McKelly, “The Double Truth,” 218.

[22] Martin Luther King, Jr., “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop,” transcript of speech delivered at Mason Temple, Memphis, TN, April 3, 1968, https://www.afscme.org/about/history/mlk/mountaintop.

[23] Lee, Do the Right Thing.

[24] Lindroth, “American Tradition,” 28.

[25] McKelly, “The Double Truth,” 223.

[26] W. J. T. Mitchell, “The Violence of Public Art: ‘Do the Right Thing,’” Critical Inquiry 16, no. 4 (1990): 898. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1343773.

[27] Lindroth, “American Tradition,” 31.

[28] Roger Ebert, “Do the Right Thing,” rogerebert.com, June 30, 1989, https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/do-the-right-thing-1989.

[29] Lee, Do the Right Thing.

Grant Dutro

Grant Dutro is a senior at Wheaton College studying economics, communication, and English. He is co-editor-in-chief of The Wheaton Record, his college student newspaper, and will be attending Vanderbilt University in the fall to pursue a master's degree in theological studies. In his spare time, you can find Grant rowing on your local body of water, reading graphic novels, or rambling about movies on Letterboxd @Dutro2003.