Laundry and the Monk's Robe: Buddhism in the Modern Era

Hygiene and cleanliness are undisputed expectations for members of civilized societies across the globe. Such hygiene may be achieved in a myriad of ways, depending on the location and resources available. The use of soaps and water is often the norm when it comes to the cleaning of clothing and fabrics. The introduction of washing machines has made cleanliness convenient, removing the need for households to spend hours scrubbing and drying fabrics. Certain fabrics demand special care, such as precious satins or embroidery, which present cleaning difficulties on a physical level and must be washed manually. There is difficulty in cleaning certain fabrics beyond the physical limitation due to sentiment or symbolic importance. In Southeast Asia, Buddhist monks living in monasteries are held to the same societal expectation of hygiene as any other civilian, but are also presented with religious demands on their outward presentation. Monks are expected by their faith to maintain a respectable appearance, treating their material clothing with great care. The saffron robe is a recognizable symbol of Buddhism and monastic life. Historically, a monk’s robe is an item that may appear to negate the strict Buddhist belief in rejecting material culture. In this study, I will determine how modern conveniences altered the traditions of cleaning monastic robes, and how the evolution of that tradition has altered the history of robes’ existence outside the realm of the material. The purpose of this research is not to argue the positive or negative connotations of forgoing certain practices, but to take a look at the reality of living as a monk in the modern era through the evolution of monastic laundry. Modernization of the treatment of robes is a change that has drastically transformed what it means to be a Buddhist monk today.

The robe lives a very different life than it did upon its creation in the time of Siddhartha Gautama. No longer is the robe a physical manifestation of rejecting material items or a dismissal of luxuries. The monk’s robe, once considered a physical extension, is now symbolic since less importance is placed on the practice of wearing and caring for the robe. The necessity of the robe is not the same kind of necessity as it was ages ago during the birth of Buddhism. Formerly, the robe was the bare minimum of coverage to keep oneself from nudity while still living the most ascetic lifestyle possible. The ascetic lifestyle of wearing rags is not practical for maintaining the outward appearance of a monk who earns alms and reverence from laypeople in the modern era. Many cities forbid begging on streets, and a monk looking as though they were experiencing houselessness while begging for alms would be in trouble with the law. Their religious role is not obvious and would be treated as vagrants [1]. The robe demonstrates the separation of holy life from ordinary life, as stated by a Thai monk I interviewed. In the time of the Buddha, the robe was less about showing one’s holiness, but rather, acceptance of a different mode of life from the ordinary.

It is important to first clarify the traditional methods of cleaning robes, as determined by the Indian founders of Buddhism, regarding the procedures and rules for a monk who wishes to clean his garment. Although different sects of the Buddhist faith have appeared over time, the practice of donning robes is seen in both of the two major schools of thought being researched: Mahayana and Theravada. Both schools of thought share the concept of rejecting attachment, delusion, and materiality, which can be exemplified in the wearing of the robe [2]. The monk’s robe is the literal rejection of materialism—decorative clothing is removed, and only a colored robe is allowed as coverage. The majority of scholarly works existing on the topic of Buddhist robes admit that there is little evidence to suggest what exactly Siddhartha Gautama would have worn after becoming the Buddha, but that he allowed the use of dyes for his followers’ robes [3]. The Venerable Dr. Paññā Nanda writes of six dyes permitted by the Buddha that were made from “roots, stems, barks, leaves, flowers, and fruits” [4]. Nanda reiterates the lack of knowledge on the original clothing worn by the Buddha and his followers up until the creation of the Vinaya [5]. What is known is that they donned the garb of ascetics, wearing rags taken from corpses or scraps thrown onto the street [6 ]. This ascetic lifestyle was an ultimate rejection of materialism and the frivolous care for appearance. Cleaning and washing were unnecessary in this mode of life. Nanda suggests the possibility that rags were bleached prior to dying, which is a form of cleaning not clearly stipulated in the Vinaya [7]. Dying and bleaching transformed the robe from mere fabric into a holy garment, and were the methods of hygienically maintaining its immaterial nature.

There are a number of rules stated as follows from the Bhikkhus’ (Monks’) Code of Discipline found in the Bhikkhu Pāṭimokkha’s “Nissaggiya Pācittiya: Rules Entailing Forfeiture and Confession,” the most important to this research being rule number four [8 ]. This rule states that none other than the monk, referred to as a bhikkhu, or his immediate relatives, may wash the robe. If this rule is not followed, the robe must be replaced.

4. Should any bhikkhu have a used robe washed, dyed, or beaten by a bhikkhunī unrelated to him, it is to be forfeited and confessed.

While creating a robe by one’s own hand may have been common at the start of Buddhism, a variety of other ways for a monk to obtain a robe have appeared. Buddhism specialist Bradley Clough discusses an important ritual related to the preparation of robe cloth that he claims has remained largely unchanged in South Asian Theravada [9]. The kathina civara puja refers to a time of offering in which laypeople make donations of robe and robe cloth to monks [10]. While other kinds of offerings are made and this ritual has further meaning in creating good relations between monks and laypeople, this paper will focus on the aspect of donating the robe cloth in this ritual as opposed to other offerings.

After a procession in which the donated cloth is carried upon the head, the cloth must be fashioned into a proper robe by cleaning, sewing, and dying. Clough does not go into detail on what this process looks like, other than it occurs during the kathina civara puja. From Clough’s perspective, this ritual is the middle ground between materialism and immaterialism, which is taught by the Buddha and promotes the involvement of laypeople in the Theravada school. Monks must not lust for material objects, but laypeople must gift items to monks in order to gain positive karma [11]. The donation of robe cloth is an appropriate donation as it is attainable by laypeople and needed by monks [12]. This practice of donating cloth can still be seen in the many Buddhist temples of Southeast Asia today. Though the specific ritual of kathina civara puja may not occur exactly as it did during the Buddha’s time, orange robe cloth is available for purchase at temples that may then be presented as donations to monks, alongside toiletry care packages. This robe fabric may be ready-to-wear or may be sold to laypeople as uncut cloth that the monk prepares himself. Whether donated in a procession or purchased from a gift shop, these robes are acceptable as proper robes for monastic use. Clough focuses much on the middle-of-the-road path that Buddha taught. His discussion relies on the notion that the robe is a manifestation of the middle way [13]. Clothing is necessary to repel cold and insects as well as to cover the body. The robe is the middle ground between shameful nudity and ostentatious decoration, making it one of the material objects necessary for monastic life.

While a robe, by its very nature, is a piece of clothing that can be donated and sewn, some scholars believe that it takes on a greater identity than just a garment. Buddhist specialist Ann Heirman takes an existential stance in explaining the purpose of the robe as much more than a simple covering for one’s body. Referring to the collective robe worn by monks throughout the lifetime of Buddhism, Heirman posits that the robe is an extension of the monk’s body [14 ]. By this logic, the robe is not an article of clothing and allows it to fall in line with the immaterialism necessary for the Buddhist monastic lifestyle, even more so for ascetic monks whose entire devotion to asceticism is the rejection of material luxuries. Citing the Vinaya's many stipulations for laundering and caring for monastic robes, Heriman relays the ways it may be cleaned. According to the Vinaya, a robe may be washed in a basin using clean water, beaten to remove dirt and dust, or dyed in the ways described by Nanda previously [15]. Ashes, mud, or cow dung may be used as cleaning materials, as the Seventh Precept forbids the use of bodily adornment, which includes perfumes or scents [16 ]. Heirman’s investigation of the Vinaya reveals an obvious importance placed on the washing of the robe in order to make it acceptable for the monastic community. Acceptable is not, however, necessarily equivalent to clean. Upon reception of a new robe, a monk must wash it and dye it per the Vinaya to bring it to the monastic standard. Since a new robe is made from unused fabric, it should be lessened in material value by bleaching or dying, or this dying process can be considered similar to a monk’s own induction into monastic life. A monk must shave his head, and a new robe must be bleached or dyed in order to gain an immaterial nature [17]. This ceremonial first washing of the robe furthers Heirman’s idea that the robe and body are one. Clough’s explanation of the middle way aligns with Heirman’s concept of the robe being an extension of the body. It is a material object that is exempt from being considered material due to its necessity.

Thích Nhất Hạnh refers to the robe of the ordained novice as “the robe of liberation, the uniform of freedom” in his book My Master’s Robe [18 ]. He recalls the way that a robe was mended by his master in preparation for his ordination. The mended robe, decades later, had become too worn-out for use, but Hạnh would continue to keep it and remember his master [19]. Though the robe had become too unseemly for Hạnh to wear in public, as it failed to maintain the respectability of a proper monk, it still served the purpose of reminding Hạnh of the universal robe’s purpose. His robe was an extension of his body and a representation of his Buddhist belief, just as Heirman suggests in her discussion of the robe’s immaterial nature being linked to its identity as an extension of the physical body.

An example of rag robe usage; old robe cloths are used to cover a broken temple decoration at Wat Chiang Mun in Chiang Mai, Thailand. Taken by author on 1/08/2024

The Venerable Paññā Nanda appears again as one of the few scholars regularly discussing the transformations of the robe in his dissertation on Buddhist robes in Myanmar/Burma. Nanda provides an in-depth and more literal explanation for the purpose of the robe in the Buddha’s time. From Nanda’s perspective, the robe is necessary for a monk to be recognized as a monk [20]. Using historical anecdotes of naked ascetics unable to be recognized as monks due to their appearance, Nanda concludes that the robe is perhaps the most important symbol of Buddhism, as the robe allows any layperson to immediately identify a monk [21]. The robe was considered just as necessary as shaving one’s head or taking vows upon entering the monkhood, as one would not fully be recognized as a novice monk if they did not have the appearance. Clough affirms this, writing that historically, Theravada monks would deny ordination to candidates appearing without a proper robe [22]. Nanda refers to the necessary appearance of a monk as “euphoric quality of pleasing personality” [23]. The robe is a sign of discipline and the calming, pleasing emotions associated with monks by laypeople [24].

In Nanda’s own detailed list of the various types of robes that may be worn, one such is the rag robe often worn by ascetics, as mentioned in his previous article. Nanda explains how the order of monks collected only rag robes, washing and sewing them, because the robes taken from corpses were often covered in maggots. Explaining the transition from rag-robes to robes or robe cloth donated by laymen, Nanda states that “This (collecting cloth from corpses) is the old tradition. Later, householders began to support monks with many requisites and other facilities. The monks accepted this convenience for leading the holy life. There were no difficulties in seeking the cloth for them” [25 ]. It is easier for one to reshape a good cloth into a robe than to first create a proper cloth from rags and then reshape that into a robe.

Methods & Limitations

The word “convenience” appeared several times in my own research. From January to April of 2024, research was conducted in Thailand, Malaysia, Taiwan, and Japan on how modern monks wash their robes. Data was collected through simple observation of monks as well as interviews with practicing or former monks. Upon visiting temples, I spoke with English-speaking monks in 15-minute conversations, with a list of questions on how they did laundry, how often new robes were acquired, if this process had changed over time, and how senior monks felt about these changes, if there were any. In some instances, correspondence was done over email, as many monks were unwilling to discuss the topic face to face with a foreign woman. All data collected was stored in a password-locked electronic document, and any names have been redacted in order to protect the privacy of the monks.

My identity as a young white woman greatly impaired my data collection due to the varying cultural norms surrounding the treatment of foreigners, as well as Buddhism’s own rules about contact between men and women. Upon arrival in Thailand, my goal of conducting face-to-face interviews became unrealistic as the majority of monks were unwilling to answer my questions. Realizing that my identity may be an obstacle, I opted to try interviewing over email correspondence in Malaysia, Taiwan, and Japan, which proved far more fruitful, evidenced by the friendly tone monks took while speaking over email. I found this form of interviewing to work best, as text-translation services are more easily available, and monks were able to take more time to prepare answers on their own schedule. In email correspondence, I introduced myself as an undergraduate student from the University of Puget Sound, making my identity as an American student forefront, as opposed to my race and gender, which are not immediately apparent in an email introduction. I found that monks were excited to speak with a student researcher.

Across all four countries, senior and novice monks alike answered these queries with confused looks, as if to say, “Why would you ask such a boring question?” These questions serve a dual purpose, as their replies will answer the straightforward question pertaining to how modern monks wash their robes. There is a significant lack of updated information on this topic, with most literature focusing on past practices and the assumption that these historical traditions apply to modern monks. These factual answers then reveal a solution to the greater question in regards to modernization of Buddhism and how this modernization heralds a transformation of what it means to be Buddhist monk, something that is very different from the original teachings of the Buddha via the stipulations laid out for monks ages ago in both Theravada and Mahayana schools.

Thailand: Urban & Ascetic

In Chiang Mai, Thailand, it is nearly impossible to step outside and not see a Buddhist monk. Throughout my own travels in Southeast Asia, Thailand displayed the greatest diversity of robes worn by monks. Many wore pristine orange robes, clearly well-cared for. As I drove towards the mountaintop temple of Wat Doi Suthep just outside the city, it was not uncommon to see a monk hiking on bare feet wearing a weathered robe of a faded orange color, so old that it almost appeared brown [26]. These are the so-called “jungle monks” whose existence was revealed to me through interviews with urban temple monks. These weathered individuals follow a lifestyle more aligned to the ascetic, which places little to no importance on outward appearance. The robe is necessary for ordination as a monk and for simple covering, but it is not intended to give the monk the “euphoric quality of pleasing personality” that Nanda explained [27]. Dr. Christopher Fisher, a former Zen monk ordained in Japan and professor at Chiang Mai University, stated over email correspondence on 1/21/2024 that this type of monk is less commonly seen as their monastic lifestyle is considered more extreme than the life of an urban monk [28]. In his experience as a Zen monk in Japan, robes were always washed by hand with the purest water available and unscented detergent. He stated that most Thai monks to his knowledge used a washing machine, also with unscented detergent, for the reason that the Seventh Precept forbids frivolous ornamentation, including perfumes [29]. However, a lemongrass scent would sometimes be used as a natural mosquito repellent, as the First Precept does not allow monks to kill living things, and disease-ridden insects must be defended against somehow. In something as simple as cleaning, the rules of monastic life are ever present and create hurdles that a layman would not have to consider.

An individual who has been an ordained monk for 26 years, currently practicing at Wat Suan Dok in Chiang Mai, gave my questions a puzzling look, as though it should be obvious that the monks at his temple simply use washing machines. In an in-person interview on 1/20/2024, he stated that “Buddhism must grow with modern society” [30]. When a temple has access to running water and electricity, there is no real reason for a monk not to utilize the modern convenience. He joined the monastery as a child in his rural village, where there was no electricity, so his robes had to be washed by hand. However, the absence of this modern convenience was the only real challenge. He expressed that once he went to a Buddhist college in the city, everyone did their laundry in washing machines. In his experience, there had been no strict rules on how a robe was washed, and he was only instructed that robe-washing was one of a monk’s “main duties” [31]. This particular monk shared the sentiment that the robe is more symbolic of ordained life than anything else. He made particular note of the fact that monks have rejected “ordinary life” and that the robes are part of “ordained life” [32]. For him, the robe demonstrates his affiliation and status as a monk. In the interview, the monk described the purpose of the robe: “The robe represents the holy man. People see the robe and recognize the holy man” [33]. The robe is something to be taken seriously, and it is no wonder that Thailand seems to be filled with Buddhist monks when they are so easily recognized by their orange robes, just as the monk said.

Malaysia: Land of Laundromats

A discrepancy can be seen between the practices of modern monks in Thailand and the strict practices outlined in Vinaya scriptures. The Vinaya scriptures explain the need for a bowl made of smooth stone with a wooden washing board, and only using ashes or dung as a cleaner [34]. This traditional laundry practice is simply not practical for modern monks who can utilize a washing machine. Buddhist monks in Georgetown, Malaysia, take modern conveniences one step further by taking their robes to a nearby laundromat [35]. While doing my own laundry, three monks sitting on the sidewalk outside of a laundromat waited as the laundress finished up their clothes, folding the fabric into a neat square as she would eventually do with mine. While standing in line, holding my bag of dirty laundry, the laundress pulled a swath of orange fabric from a dryer and folded it into a square before taking a load of laymen’s clothes and tossing it in the same now-empty dryer. There was no separate facility or machines for the monks’ robes, which goes against monastic rules of monks coming in contact with women or items directly handled by women [36]. At a temple, a woman bringing food must place it on a table for a monk to receive, rather than handing it directly to a monk [37]. In the image below, a laundress handles the robes, ironing and folding them before handing the finished product to the monk.

A Muslim laundress folds a washed monk’s robe at her laundromat in Georgetown, Penang, Malaysia. Taken by author on 2/10/2024

The monks did not do their laundry themselves, and they hired a Muslim laundress. This difference of faith may be the loophole that monks are able to exploit in order to utilize the modern convenience of a laundromat. As long as the service used is not Buddhist-run, then it cannot be expected to abide by Buddhist rules, and the monks may use it freely. Nor is this service any act of donation or charity to acquire good karma. The monks, having paid for their laundry, take the robes and go on their way. In Malaysia, convenience is once again key. This strict taboo of contact with a woman has fallen by the wayside in the name of practicality.

Monks in peninsular Malaysia display little variety in the types of robes worn. Colors rarely stray from a bright orange that borders on fluorescent. This similarity in color across the country points to most robes being of similar fabric content that holds orange dye in one way. Logic allows for the possibility that monks are able to wash their robes in similar ways. The trio who retrieved their orange robes from the laundromat did not hide how they cleaned their garments. Similarly, the fact that there was a small group displays that hiring others to do laundry was not the action of one renegade monk who did not want to wash by hand. Laundromats are a common convenience across peninsular Malaysian cities, and were by far the most common way for anybody, laymen and monks alike, to get their laundry done.

Taiwan - Work, Work, Work

Unlike in Malaysia, in Taiwan, in-house washers and dryers proved to be the path to cleanliness. Fo Guang Shan is a large temple complex and monastery in Kaohsiung in southern Taiwan. Described to me as a “Buddhist Disneyland” by a Taiwan local, this location gives laymen the chance to spend time living as and learning from a monk [38]. These monks are quite used to living in an environment that caters to the fast-paced lives of non-monastic people. Reaching out through email correspondence, I posed the same questions asked of monks in Thailand and Malaysia to an English-speaking monk living at Fo Guang Shan, who provided answers and further information through multiple email correspondences over several days. His answers to the core query were not dissimilar from what was discovered in the previous countries visited, though he did state that a laundromat would not be practical to serve the large capacity of this particular temple [39]. Washing by hand is still done by some monks who feel that it is a mindful activity, but washing using a machine would also leave more time for other mindful activities, so there is no wrong action either way. The only time that a monk in Taiwan was specifically instructed to wash by hand would be in a monastic college to teach mindfulness, but it is no longer necessary once mindfulness has been learned and the graduated monk moves on to temple life [40]. Monastic students at Fo Guang Shan are given a specific time slot before their evening meal to take care of hygiene, including washing robes if needed [41]. Once one is a fully ordained monk, washing is done whenever the monk has time [42]. The only instance in which a monk might not wash his own robes is if a senior monk has a novice assistant, or if a senior monk is too frail to do the washing himself and requires help [43]. This monk pointed me to the translated Pali Vinaya texts by Thanissaro Bhikkhu that discuss the many rules and history of the robes in Buddhism. To my surprise, he admitted that this chapter was too boring to warrant him reading all of it, calling it “irrelevant to our time” and instead found interest in other chapters [44]. This monk confirmed that washing robes in the way that the Buddha would have, using dung or ashes as detergent, would be quite gross and incredibly impractical today.

Taiwan and its Chinese-oriented version of Buddhism abandoned the strict rules of robes quite a while ago. As the monk I spoke with recalled, those who first practiced Buddhism in China were members of the nobility who were not fond of ascetic appearances and opted for more opulent robes inspired by Tang dynasty styles. The monk from Fo Guang Shan told me via email correspondence that “Buddha used clothes that fit in with Indian culture. The Chinese wanted Chinese cultural clothes. I want jeans and a T-shirt” [45]. This Taiwanese monk said he wanted jeans and a t-shirt, as it is part of his culture as a modern person. The Taiwanese monk treats his robes as though there were something like a t-shirt by tossing them into the washing machine, so is there actually any difference between a robe and a t-shirt? If the robe is nothing but symbolic to modern monks, is the change to laymen’s clothing such an impossibility? With monks saying that Buddhism must keep up with the times, one cannot help but wonder what will happen if one day young monks really do ask to wear ordinary clothing.

Japan - Invisible yet Respectable

As a Confucian-based society, there is great importance placed on constant work in Japan. As the monk at Fo Guang Shan told me: “Work, work, work, lots of busy work. Work is good for you. Lots of work is even better” [46]. The focus on labor is one instance in which Buddhism has shifted. The Buddha was against monks working so that meditation could be prioritized. To certain monks, work is meditation. When it comes to laundry, washing can be a form of work/meditation. In Japanese temples, monks utilize in-house washing machines as well. A priest at a Jodoshu Buddhist temple told me over email correspondence that using a washing machine saves time for other activities, just as I was told in Taiwan. He stated that even in training, he used a washing machine, and that most students use machines nowadays [47]. It is simply understood that washing by hand creates mindfulness, but it is no longer practical to do so when a washing machine is available. When asked how older senior monks felt about the use of washing machines, the priest told me that it is so common nowadays that any discomfort is long gone. A monk from a different Buddhist temple told me the same: that the elder monks may have at first been disappointed seeing novices toss their clothes into a washing machine, but soon accepted it as the norm for washing robes.

The revelation that Japanese monks utilize washing machines differs greatly from the information provided by Dr. Christopher Fisher, a Zazen monk, who stated that Zen, or Chan, monks would always wash with the cleanest water at hand. Zazen Buddhism places heavy focus on meditation and meditative acts, as it is based around the practice of meditation by Siddhartha Gautama. It is the Zen belief that meditation is what leads the practitioner to enlightenment and Buddhahood [48]. The meditative quality of washing robes by hand is not lost in Zazen Buddhism [49]. However, as expressed by the Jodoshu monk, many monks across the country still used a machine. They are taught that washing by hand is a meditative act, but forego it in favor of other meditations.

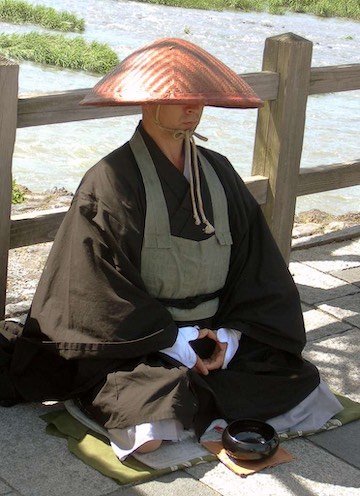

Japanese Buddhist monk by Arashiyama. Photo by Ivar Leidus, via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Japan differed greatly from the other countries in the research, not because of a change in method when it came to laundry, but by the mere fact that monks were not as publicly visible. In Thailand, monks were often in public, but in Japan, one had to visit a temple. Even then, seeing a monk would not be guaranteed. I was told by monks in Thailand, Malaysia, and Taiwan that part of the importance of washing the robe was about public appearance. However, the point of maintaining good appearances seemed null in a place where monks were hardly seen in public. With the establishment of the fact that robes nowadays are physically treated as normal garments and less as extensions of the body, the point of a respectable public appearance does indeed make sense, particularly in Japan, despite the generally invisible presence of monks at work. In Japanese cities, one will witness seas of black suits as people head to and from office buildings. Although office work takes place inside office buildings and is out of the public eye, the expectation to be well-dressed is still very prevalent. Even Japanese schoolchildren must wear pristine uniforms [50]. Monks growing up in Japanese society are well-versed in the practice of appearing clean and orderly while working, regardless of the outfit.

While perhaps calling monkhood a career is inapt, it is a lifestyle that can be considered as intense as the life of a working person in Japan. Brian McVeigh writes of the seken, a sphere of peers who hold important opinions and may watch or judge the moves of others, whether it be a neighbor, coworker, or boss [51]. Japanese individuals do not live judgment-free lives, and a monk is still a Japanese individual. Monks are expected to keep up a professional, honorable appearance, even if public sightings are few and far between; the seken is ever present [52]. Though the seken is a Japanese concept, it is not necessarily exclusive to Japan. This idea that a monk possesses a sense of calm euphoria is best demonstrated by an outward appearance that anybody can recognize as positive. Clear communication of one’s role, purpose, and motives is of great importance in modern Buddhism’s relationship with the laymen public.

Concluding Remarks

Today, monks still wear the robe, but do not utilize it in a way that is different from ordinary life. Rather, the robe is now one of the few connections to ordinary life as a facet that has remained unchanged from laymen to the monastic lifestyle. A monk in today’s monasteries eats only one meal a day, chants verses, and cleans the temple grounds. Their hygienic needs are one of the few things they do on their own terms, and the choice to do laundry in whatever manner is a freedom that allows monks to live monastic life while still maintaining a sense of normalcy. Though it is necessary for a holy man to be recognized as an extraordinary individual, there is no need to be othered by society for overly traditional practices.

A monk waits for his laundry to finish at a laundromat in Georgetown, Penang, Malaysia. Taken by author on 2/20/2024

A monk in Taiwan explained that it is important to think about how hygienic practices really would’ve worked in the past when it comes to questions about monastic life during the birth of Buddhism. Though this was in response to a question regarding how a monk would wash their robes, it is connected to the larger question of how Buddhist practices have changed with the acknowledgment that monks live a life very different from those of the past. Multiple times in interviews, monks stated the need for Buddhism to progress with the times to maintain relevance and practicality for followers. Allowance of modern conveniences is hardly seen as a wrong action in Buddhism, though one might argue it is the use of a luxury that completely negates the teachings of the Buddha. Why is it that this aspect of the ascetic lifestyle is something forgone in favor of modernity? An aspect of modern times is marketability, and Buddhism must be marketable to survive.

Based on the ways that monks across Asia nowadays take care of their robes, is the robe truly liberating anymore? To some, loss of tradition is not a bad thing; rather, quite the opposite. As mentioned, the purpose of this research is not to argue the positive or negative connotations of forgoing these practices, but to understand the reality of living as a monk in the modern era through the evolution of monastic laundry. The Buddha’s rules, written in the Vinaya regarding the creation and washing of robes, are treated as a concept of the past. When the robe is no longer being treated as an immaterial thing and instead as a material object, one of the core values of the Buddhist monastic lifestyle, the shedding of material objects, is lost. This is but one step of the transformation of Buddhism into something that could not have existed previously in the modern era. Modern Buddhism is far less related to the striving for enlightenment, as practitioners cut corners in some of the tasks that the Buddha laid down as stepping stones to Nirvana. Instead, they opt for new avenues that have arisen in modernity, focusing on the public in an age where appearances matter. Modern monks learn about the historical practices of immaterialism but are not expected to actually implement them in their everyday lives. Merely understanding the benefits of immaterialism is a suitable replacement for historical ascetism. Forgoing the strict practice of immaterialism, beginning with the monks’ robe, is one way that Buddhism has kept up with contemporary society and prevented itself from becoming obsessed with traditions that are no longer practical to individuals in the modern era.

Endnotes

[1] R. Rusenko and Debbie YM Loh, 2015 "Begging the destitute persons act 1977, and punitive law: an exploratory survey,” 5-6.

[2] Dr. Jinabodhi Bhikkhu, 2011, “Theravada and Mahayana: Parallels, Connections and Unifying Concepts,” in Unifying Buddhist Concepts.

[3] Ven. Paññā Nanda, Phramaha Nantakorn Piyabhani, Dr., Asst. Prof. Dr. Sanu Mahatthanadull, 2018, Development of Monastic Robe (Cīvara) in The Buddha’s Time.

[4] Ibid. 58.

[5] Ibid. 59.

[6] Ibid. 60.

[7] Ibid. 58.

[8] Thanissaro Bhikkhu, translator, 2007, Bhikkhu Pāṭimokkha: The Bhikkhus' Code of Discipline, part 1, translated from Pali.

[9] Bradley Clough, 2015, “Monastic Matters” in Sacred Matters: Material Religion in South Asian Traditions. Albany: State University of New York Press, 177.

[10] Ibid. 177.

[11] Ibid. 176.

[12] Ibid. 178, 180.

[13] Ibid. 179.

[14] Ann Heirmann, 2014, “Washing and Dying Buddhist Monastic Robes,” 469-470.

[15] Ibid. 569-470.

[16] Dr. Christopher Fisher, 2024.

[17] Ann Heirmann, 2014, “Washing and Dying Buddhist Monastic Robes,” 484-485.

[18] Thich Nhat Hanh, 2002, My Master's Robe: Memories of a Novice Monk. Berkeley: Parallax Press, 96.

[19] Ibig. 98.

[20] Ven Paññā Nanda, 2017, "An Analytical Study of Development of Myanmar Robes (CĪVARA): From the Buddha’s Period to the Present Time,” 12.

[21] Ven Paññā Nanda, 2017, "An Analytical Study of Development of Myanmar Robes (CĪVARA): From the Buddha’s Period to the Present Time,” 6-17.

[22] Bradley Clough, 2015, “Monastic Matters,” 173.

[23] Ven Paññā Nanda, 2017, "An Analytical Study of Development of Myanmar Robes (CĪVARA): From the Buddha’s Period to the Present Time,” 18.

[24] Ibid. 18.

[25] Ibid. 23.

[26] Observed at Wat Doi Suthep, located on a mountain outside the city of Chiang Mai, Thailand, is a stupa and temple complex attracting many Buddhist pilgrims and tourists alike. A symbol of Chiang Mai, it is said to house a relic of the Buddha carried there on the back of a white elephant. (Tourism information from Wat Doi Suthep, 1/11/2024).

[27] Ven Paññā Nanda, 2017, "An Analytical Study of Development of Myanmar Robes (CĪVARA): From the Buddha’s Period to the Present Time,” 18.

[28] Dr. Christopher Fisher, email correspondence, 1/21/2024.

[29] Dr. Christopher Fisher, email correspondence, 1/21/2024.

[30] Anonymous monk, Wat Suan Dok, Thailand, in-person interview, 11/20/2024.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Ann Heirmann, 2014, “Washing and Dying Buddhist Monastic Robes,” 472-473.

[35] Observed at 123 Laundry, Georgetown, Penang, Malaysia 2/10/2024.

[36] Thanissaro Bhikkhu, translator, 2007, Bhikkhu Pāṭimokkha: The Bhikkhus' Code of Discipline, Part 1, translated from Pali.

[37] Ibid.; observed at Buddhist temples in Thailand in January 2024.

[38] Anonymous Taiwanese individual, in-person interview, 3/11/2024.

[39] Anonymous monk, Fo Guang Shan, Taiwan, email correspondence, 3/22/2024.

[40] Ibid. 3/22/2024.

[41] Ibid. 3/22/2024.

[42] Ibid. 3/26/2024.

[43] Ibid. 3/26/2024.

[44] Ibid. 3/26/2024.

[45] Ibid. 2/26/2024.

[46] Ibid. 3/26/2024.

[47] Anonymous monk, Jodoshu Temple, Japan, 4/09/2024.

[48] Akira Kasamatsu and Tomio Hirai, 1963 "Science of zazen." Psychologia 6, no. 1-2, 87.

[49] Dr. Christopher Fisher, 2024.

[50] Brian McVeigh, 1997. "Wearing ideology: How uniforms discipline minds and bodies in Japan." Fashion Theory 1, no. 2, 190-191.

[51] Ibid. 193.

[52] Ibid. 193, 195.

Audrey Glaubius

Audrey Glaubius is a graduating senior at the University of Puget Sound, earning her B.A in Art History with a Minor in Asian Studies. Much of her undergraduate research is inspired by a passion for fashion and her experiences abroad in Southeast and Eastern Asia. When she’s not studying Buddhist art, you can catch Audrey swapping gossip with friends on KUPS 90.1 FM, or sewing something impractical during her shift in the campus Makerspace.