The “despised Hebrew”: Identifying Antisemitism in Victorian Popular Culture, 1835-1895

Introduction

Throughout the nineteenth century, Jews in England gradually acquired political rights and increasingly gained access to English society. In 1835, Jews were “emancipated” (gained citizenship rights), and received the right to vote. The Universities Tests Act of 1871 permitted Jews to attend and work at the Universities of Oxford, Cambridge, and Durham.[1]

Despite these improvements, Jews in Victorian England continued to face persistent antisemitism in their everyday lives. Victorian popular culture in particular was one of the most prominent arenas in which antisemitism surfaced. Acclaimed writers such as Charles Dickens (1812–1870) and George du Maurier (1834–1896) drew upon classic antisemitic tropes in their works. From describing Jewish characters as physically repulsive to exposing their manipulative, villainous, and corrupt monetary practices, Victorian authors and journalists employed antisemitism to isolate Jews from British society and to express Christian English superiority.

Antisemitism does not appear arbitrarily. In nineteenth century English society, antisemitism resulted from long-standing antipathies towards Jewish people combined with societal conditions. This aggression becomes evident through a microhistorical analysis of antisemitism in Victorian popular culture. Thus, by analyzing Charles Dickens’s Oliver Twist and George du Maurier’s Trilby, this paper argues that while Victorian authors used antisemitic stereotypes because of historically ingrained hostilities towards Jews, antisemitism also arose as a response to particular circumstances and conditions that emerged in England during the nineteenth century. Economic strife among the English poor, fascinations and anxieties surrounding notions of gender and sexuality, and increased immigration of Jews from Eastern Europe are just a few of these inciting circumstances.

Historiography surrounding Victorian literature and English-Jewish history demonstrates how authors utilized antisemitic stereotypes in their works. Scholar Vitória Ávila Fioravanti discusses how these antisemitic prejudices are evident in Dickens’s Oliver Twist, a novel about an orphan named Oliver who faces hardships in nineteenth-century London, including abuse in a workhouse and involvement with a pickpocket gang. Fagin, the Jewish leader of the pickpocketing gang, embodies these antisemitic prejudices through his characterization as physically repulsive, financially corrupt, and morally depraved.[2] Susan Meyer explains Dickens’s reasoning for portraying “the Jew” in this manner, asserting that Fagin served as a moralizing corrective figure and that antisemitism was used as a rhetorical tool to instruct Englishmen toward a benevolent Christian society. In other words, Fagin’s Jewish identity demonstrates how English society ought to undermine Jewish malevolence, and work towards a Christian society characterized by philanthropy, compassion, and generosity towards the poor.[3]

Similarly, other scholars have remarked on George du Maurier’s incorporation of antisemitism in his novel Trilby. Originally published in 1894, Trilby tells the story of Trilby O’Ferrall, a half-Irish model for artists and a laundress in Paris, who succumbs to Svengali’s, a Jewish hypnotist and musician, spell. Svengali, a failed musician, hypnotized Trilby, whom he was in love with, to be a profoundly gifted singer. The pair performed at concerts throughout Europe with Trilby as “La Svengali,” and Svengali as the orchestral conductor. At the end of the novel, when Svengali dies, Trilby loses the spell and her enchanted voice.[4] Sarah Gracombe discusses how du Maurier used the character Svengali to demonstrate English society’s cultural deficiencies. Meanwhile, Anna Peak showcases how the Victorian public displaced simultaneous anxieties and fascinations about gender and sexuality onto Svengali, who is represented as an effeminate and sexually transgressive Jew. These scholars reveal how antisemitism functions as a result of both ingrained prejudices and immediate responses to recent societal developments.

These historians and literary scholars explain how Victorian authors encouraged antisemitism. However, they view these works as separate incidents of antisemitism, disconnected from both each other and places, like Eastern Europe. This limited perspective precludes a comprehensive understanding of the interwoven character and global ramifications of antisemitism during the Victorian era. Rather, placing Victorian popular culture in a more nationalized and interconnected context demonstrates how antisemitism is both historically ingrained and reactive. Exploring these works in relation to each other reveals how antisemitism in Victorian popular culture is part of an interlinked historical phenomenon of hostility toward Jews.

Oliver Twist

In Oliver Twist, the Jewish antagonist, Fagin, notably portrayed as physically repugnant, embodies several traditional antisemitic stereotypes. Dickens introduces Fagin as “a very old shrivelled Jew, whose villainous-looking and repulsive face was obscured by a quantity of matted red hair.”[5] Fagin’s red hair is particularly significant, symbolizing, as Leonid Livak discusses, the classic connection between red hair on Jews and their embodiment of the eternal flames of hell.[6] This representation is pervasive throughout the novel, as Dickens further describes Fagin as a “loathsome reptile” with a “face wrinkled into an expression of villainy perfectly demoniacal.”[7] Dickens uses Fagin’s physical repugnance as the emblem of his moral corruption, a trope that precedes nineteenth-century popular culture and cultural imagery.

In addition to his physical traits, Fagin is manipulative, miserly, greedy, and corrupt, all qualities among the most persistent manifestations of antisemitism. Throughout the novel, Fagin treasures the stolen items his surrogate orphaned children pickpocketed for him while displaying no love, genuine friendship, or affection towards them. In essence, Fagin is a miser who prioritizes greed and wealth over empathy and compassion.[8] In Chapter 9, Fagin is shown cherishing his secret collection of expensive jewelry, and examining each item “long and earnestly.”[9] Yet, despite Fagin’s mass fortune, his orphaned children remain destitute and reside in ramshackle living quarters, which further demonstrates his tremendously selfish and corrupt qualities.

Finally, Fagin represents the deeply historical stereotype of Jews as fundamentally immoral and depraved. During Fagin’s imprisonment, “he began to think of all the men he had known who had died upon the scaffold; some of them through his means [...] and had joked too, because they died with prayers upon their lips.”[10] Throughout his career, Dickens made several private remarks about Jewish cruelty and immorality. For example, despite denying accusations of antisemitism, Dickens affirmatively wrote to his acquaintance, Eliza Davis, that “the class of criminal almost invariably was a Jew.”[11] This statement underscores Dickens’s equating Fagin’s Judaism with his criminal behavior and personal corruption. For Dickens, there was no better way to explain Fagin’s overt immorality than to constantly mention his Judaism.

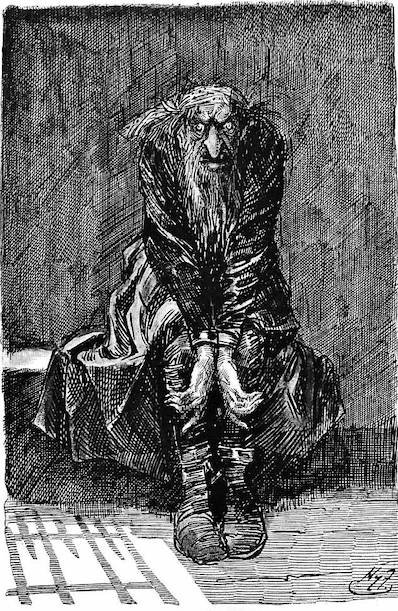

Figure 1, Oliver Twist introduced to the respectable old gentleman by George Cruikshank, 1903. Illustration for the Collector’s Edition of Oliver Twist. Scanned Image and Text by Philip V. Allingham for The Victorian Web. https://victorianweb.org/art/illustration/cruikshank/ot5.html

Dickens’s portrayal of Fagin and his use of prejudice against Jews represents antisemitism’s simultaneous ingrained and reactive nature. Fagin is a product of long-standing antisemitic sentiments that inevitably penetrated nineteenth-century England. Dickens employed antisemitism as a reaction to contemporary Victorian issues, as a result of enduring antisemitic tropes seeping into English society. Fagin’s financial corruption is of key importance for Dickens, who advocated for enhanced poor relief in England. Fagin embodies Dickens’s critique of English society’s maltreatment of the poor, using antisemitism to contrast Judaism with Dickens’s ideal altruistic society.[12]

Susan Meyer discusses Dickens’s Christian influences in Oliver Twist, and rightly asserts that his advocacy for the English poor stems from Christian rhetoric.[13] It is not surprising that Fagin, who represents English society’s deficiencies in addressing poverty, is bereft of so-called “Christian virtues.” For Dickens, Judaism is the inverse of Christianity. Fagin assumes the role of a moral instructor, guiding English Christians to steer away from his unchristian actions and disposition. Dickens underscores the idea that Christian values preclude moral corruption and maltreatment towards the poor while Fagin and Judaism promote such vices. By employing antisemitic rhetoric and juxtaposing Judaism against Christianity, Dickens warns against acquiring Fagin’s deviant behavior and encourages Englishmen to diverge from innately Jewish transgressions. Thus, Fagin and the rhetoric of antisemitism serve as ethical guides, orienting the audience toward a collective improvement in poor relief, philanthropy, and benevolence.

This utilization of Fagin as a moral guide towards a benevolent English society is best exemplified in the last chapter of the novel: “Fagin’s Last Night Alive.” As the name suggests, the morally corrupt and unchristian Fagin is hanged. His death bears extreme significance, as Dickens, according to Meyers, “symbolically purges the novel’s representative of the absence of Christianity” and prepares “the way for a vision of a purified England in the idyllic village, with the church at its moral center.”[14] Therefore, Fagin’s death facilitates the emergence of Dickens’s imagined benevolent Christian English village, with the church at the center and residents who embody Christian values of compassion and philanthropy. This vision, which was impossible to imagine while Fagin was alive, counters the blemished society portrayed at the novel’s beginning. Hence, Dickens implies that a society with Jewish traits of selfishness, malevolence, and moral and financial depravity preclude an idyllic England.

Figure 2, Fagin in the Condemned Cell by Harry Furniss, 1910. Illustration for Oliver Twist. Scanned Image and Text by Philip V. Allingham for The Victorian Web. https://victorianweb.org/art/illustration/furniss/ot33.html

Dickens further highlights his antisemitic implication that Judaism is the antithesis of Christianity in writing of Fagin’s irredeemable condemnation and inability to reach salvation. The character Bill Sikes, a robber and murderer in Fagin’s gang of pickpockets, is not Jewish, but is portrayed to be as evil as Fagin. Yet, despite brutally murdering the woman who loved him, Sikes still had access to atonement and salvation. Conversely, Dickens does not extend this mercy or redemption to Fagin, who is “unable to hear the message of hope in the striking of the church clocks; he must experience hellfire in the feverish burning of his flesh.”[15] To represent Judaism as Christian morality’s counterpart, Dickens renders Fagin as destined for damnation, unable to achieve clemency and salvation.

Despite these antisemitic references, Dickens rejected accusations of antisemitism in his works. In a letter dated June 22nd, 1863, Ms. Davis admonished the globally renowned author for his antisemitic depiction of Oliver Twist’s antagonist, Fagin. She wrote:

It has been said that Charles Dickens, the large hearted, whose works plead so eloquently and so nobly for the oppressed of his country, and who may justly claim credit, as the fruits of his labour, the many changes for the amelioration of the condition [of the] poor now at work, has encouraged a vile prejudice against the despised Hebrew.[16]

Dickens was shocked by Ms. Davis’s accusations.[17] He denied that Fagin was pernicious to Jews, and rejected accusations of antisemitism. A year later, Dickens wrote Our Mutual Friend, featuring a benevolent and altruistic money-lending Jewish character, Mr. Riah. Literary critics such as J. Mitchell Morse assert that Mr. Riah, despite being unrealistically compassionate, served as a way for Dickens to apologize for his antisemitic portrayal of Fagin, and refute Ms. Davis’s accusations.[18] Further, in the 1867 edition of Oliver Twist, Dickens edited out the many instances of antisemitism that Ms. Davis referred to, including replacing the words “the Jew” (which appeared 257 times throughout the novel) with other qualifiers.[19] Clearly, Dickens was aware of the gross antisemitism pervasive throughout Oliver Twist. This begs the question: why did Dickens actively choose to employ antisemitism in his negative depiction of Fagin?

Trilby

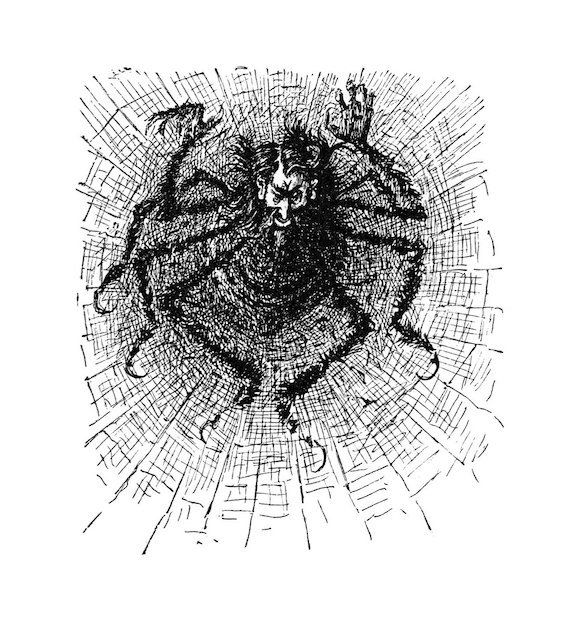

Dickens is not the only literary author who harnesses antisemitism in their works. George du Maurier’s Trilby uses the Jewish character, Svengali, as an ethical guide to instruct Englishmen toward a more virtuous England. Both Dickens and du Maurier portray Jews as fundamentally different and inferior to English Christians, incapable of assimilating into English society. Du Maurier draws upon the antiquated stereotype of Jews as manipulative and in possession of supernatural powers. Svengali hypnotizes Trilby not only to fulfill his musical dreams, but also to place Trilby under his complete control. When Svengali hypnotizes Trilby, he proclaims to her, “you shall see nothing, hear nothing, think of nothing but Svengali, Svengali, Svengali!”[20] Du Maurier strips Svengali of his humanity, portraying the Jewish character as possessing inhuman powers that only belong to the supernatural. As Gracombe explains, Svengali’s mystic and cunning characteristics stem from “a long tradition in which Jews were thought to have ‘special powers’ – be they musical, mesmeric, medicinal, poisonous, or all of the above.”[21] Svengali’s Jewishness explains his desire for complete control over Trilby using intangible cognitive abilities.

Figure 3, Svengali as a Spider in his Web by Harry Furniss, 1895. Illustration forTrilby.

However, while this is a long-standing Jewish trope, du Maurier also uses antisemitism to react to particular cultural deficiencies in English society. Du Maurier suggests that because Jews possess innate tendencies towards creativity, they are different from and subordinate to Englishmen. According to Gracombe, “good art, and the appreciation of good art, is conjoined to something foreign, literally or metaphorically outside England’s borders.”[22] For du Maurier, all of Svengali’s characteristics, including his creativity, stem from his inferior Eastern-European Jewish heritage, thus attributing to him a distinctly subordinate non-English identity.[23] George Orwell most clearly expresses du Maurier’s antisemitism in one of his “As I Please” columns:

It is queer how freely du Maurier admits that Svengali is more gifted than the three Englishmen, even than Little Billee, who is represented, unconvincingly, as a brilliant painter. Svengali has ‘genius’, but the others have ‘character’, and ‘character’ is what matters. It is the attitude of the rugger-playing prefect towards the spectacled ‘swot’, and it was probably the normal attitude towards Jews at that time. They were natural inferiors, but of course they were cleverer, more sensitive and more artistic than ourselves so such qualities are of secondary importance. Nowadays the English are less sure of themselves, less confident that stupidity always wins in the end, and the prevailing form of antisemitism has changed, not altogether for the better. [24]

Because Jews possess creative brilliance rather than “character,” du Maurier indicates that Jews maintain a distinct and inferior status to Englishmen.

Furthermore, du Maurier used Svengali’s artistry not only to isolate Jews and render them inferior, but also to criticize the lack of English artistic culture and affinity. For du Maurier, England did not appreciate the arts, but viewed them as “but an agreeable pastime, a mere emotional delight, in which the intellect has no part.”[25] Svengali serves as a creative guide to counter what du Maurier perceives as English cultural ignorance of the arts. Du Maurier desires Englishmen to be more like Svengali, who appreciates art and possesses creative proclivities. While this may seem like du Maurier praises Svengali for his artistic genius, he ultimately concludes that an excess of Jewish culture can detrimentally obstruct English society. Du Maurier suggests that while Englishmen should model their creative development after Svengali’s artistry, Svengali still uses his creativity to manipulate Trilby and his audiences. Du Maurier advocates for more Jewish artistry in English culture, however, not up to the point where it becomes disruptive to English society.[26] The fact that du Maurier would consider any dose of Jewishness in English culture as such implies Jewish cultural inferiority and inherent vindictiveness.

Figure 4, “We took her voice note by note,” 1894. Illustration for Svengali and Trilby in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine. Scanned Image and Text by Philip V. Allingham for The Victorian Web. https://victorianweb.org/art/illustration/dumaurier/trilby/118.html

Du Maurier also uses Svengali to respond to fascinations and anxieties regarding gender and sexuality. Rhetoric surrounding sexual “depravity” and gender transgressions in Victorian culture was concurrently discouraged, yet fascinating to the public. Trilby simultaneously promotes and chastises sexual and gender transgressions in a manner that correlates to du Maurier’s underlying antisemitism. Du Maurier portrays women dressed as men, men obsessed with feet, and men living and sleeping together only when displaced onto the Jew Svengali. In other words, du Maurier could only discuss issues related to gender and sexuality with sympathy when projected onto Svengali.[27] Hence, Svengali’s effeminacy and queerness enhanced Trilby’s public appeal, as it permitted Victorians to engage in discourse about gender and sexuality by projecting their anxieties and fascinations onto this distinctly Jewish character.

Svengali’s sexuality and gender fluidity are most clearly expressed through his choice of instruments. The piano, in particular, embodied Svengali’s femininity and sexuality for several reasons. It is a domestic instrument, and domesticity was closely associated with women and femininity. Victorian society discouraged women from being out in public alone, so the piano served to keep women in the domestic sphere and supervise their behavior.[28] Also, the piano was closely linked to expressive emotionality and sentimentality, which was associated with femininity. Finally, the piano reflects Svengali’s sexual transgression, through his predatory “languishing expression,” “leer[s],” and “ogle[s],” as he plays the piano for his audience.[29]

Conclusion

Eliza Davis’s accusation of antisemitism against Dickens highlights a larger point about antisemitism and Victorian popular culture. While Dickens and du Maurier employed antisemitic stereotypes dating to antiquity, they also employed Jewish stereotypes in response to particular developments in Victorian society. Charles Dickens, responding to malevolence towards the English poor, utilized the Jewish antagonist Fagin, as a moral guide, and antisemitic rhetoric, as an instructional model, to illustrate unchristian and immoral behavior. Similarly, George du Maurier used the Jewish musician and hypnotist Svengali as a medium to critique England’s lack of artistic creativity. He also appealed to English society’s anxieties and fascinations with gender and sexuality by feminizing Svengali, and rendering him sexually transgressive.

In order to reveal the reasons as to why antisemitism emerges, scholars must analyze antisemitism in Victorian popular culture works as interconnected elements. Examining antisemitism in Victorian cultural imagery reveals how this profoundly persistent prejudice manifests because of historically ingrained ideas, as well as in reaction to particular societal circumstances or situations.

Notes

[1] Universities Tests Act 1871, c. 26. Available at: https://library-guides.ucl.ac.uk/harvard/act-parliament (5 October 2023).

[2] Vitória Ávila Fioravanti, “I Am a Jew: The Representation of Jews and Antisemitism in British Literature and Culture,” Porto: Universidade Do Porto Faculdade de Letras, 3, 11, no. 1 (2022): 27–40, 11-13; Charles Dickens, Oliver Twist, 1st ed. (New York: Open Road Integrated Media, Inc., 2010).

[3] Susan Meyer,. “Antisemitism and Social Critique in Dickens’s ‘Oliver Twist.’” Victorian Literature and Culture 33, no. 1 (2005): 240.

[4] George du Maurier, Trilby (London: Osgood, Mcilvane, and Co., 1894).

[5] Charles Dickens, Oliver Twist, 1st ed. (New York: Hurd and Houghton, 1874), 98.

[6] Leonid Livak, The Jewish Persona in the European Imagination: A Case of Russian Literature (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2010), 90.

[7] Dickens, Oliver Twist, 211, 216.

[8] Ávila Fioravanti, “I Am a Jew,” 38.

[9] Dickens, Oliver Twist, 103.

[10] Dickens, Oliver Twist, 287.

[11] Murray Baumgarten, “‘The Other Woman’—Eliza Davis and Charles Dickens,” Dickens Quarterly 32, no. 1 (March 2015): 44–70, 55.

[12] Meyer, “Antisemitism and Social Critique,” 241.

[13] Meyer, “Antisemitism and Social Critique,” 239

[14] Meyer, “Antisemitism and Social Critique,” 240-241

[15] Meyer, “Antisemitism and Social Critique,” 250.

[16] Mrs. Eliza Davis, “To Charles Dickens,” 22 June 1863. In Susan Meyer, “Antisemitism and Social Critique in Dickens’s ‘Oliver Twist,’” Victorian Literature and Culture 33, no. 1 (2005): 239–52, 239.

[17] Davis, “To Charles Dickens,” 239–52, 239.

[18] Josiah Mitchell Morse, “Prejudice and Literature,” College English 37, no. 8 (April 1976): 780–807, 790.

[19] Meyer, “Antisemitism and Social Critique,” 240.

[20] du Maurier, Trilby, 72.

[21] Sarah Gracombe, “Converting Trilby: Du Maurier on Englishness, Jewishness, and Culture,” Nineteenth-Century Literature 58, no. 1 (2003): 75–108, 102.

[22] Gracombe, “Converting Trilby,” 92.

[23] Gracombe, “Converting Trilby,” 92.

[24] George Orwell, “As I Please,” story, in The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell: In Front of Your Nose 1945-50, ed. Sonia Orwell and Ian Angus, vol. 4 (New York: Secker & Warburg, 1968), 252–53.

[25] du Maurier, Trilby, 240.

[26] Anna Peak, “That Flexible Flageolet: Music, Homophobia, and Anti-Semitism in George Du Maurier’s Trilby,” Interdisciplinary Literary Studies 21, no. 4 (2019): 476–92, 486-487.

[27] Peak, “That Flexible Flageolet, 477-478.

[28] Arthur Loesser, Men, Women and Pianos: A Social History (New York: Dover Publications, 1990), 64.

[29] du Maurier, Trilby 19, 42; Peak, “That Flexible Flageolet,” 485.

Robert Coleman

Robert Coleman is an undergraduate student at William & Mary studying History and Judaic Studies, and is scheduled to graduate in May 2025. He is currently writing his honors thesis project tentatively titled “‘The Ground Moved’: Examining the Holocaust in Zhytomyr, Ukraine, 1941-1943,” which seeks to analyze the history of the Holocaust in the city of Zhytomyr, Ukraine, from the perspective of Jews and witnesses of Nazi genocide. He hopes to pursue a PhD in history and is broadly interested in issues relating to Jewish history, Holocaust studies, and Memory studies.