Model Off Duty: The Life of Elizabeth Siddall in Poetry and Paintings

Introduction

A “supermodel” of the Victorian Era, Elizabeth Siddall (1829–1862) is forever memorialized in the paintings and poetry of the men she sat for, the Pre-Raphaelite Brothers, including her eventual husband, Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882). However, the depictions of Siddall created by these men are not authentic. They captured her likeness to create characters, using her image to tell stories of literary and historical figures and heroines of myths and legends—all with an aesthetic, romantic, and sensual undertone. Siddall was a face and body used for the Pre-Raphaelite method of art for art’s sake. An artist in her own right, Siddall is survived by her poetry and paintings. After Siddall’s death, few of her letters and diaries remained. Any conclusions made about her actual life and personality are drawn from these bodies of work. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood’s portrayal of Siddall in their art and poetry created a narrative of her life that, when compared with Siddall’s own art, romanticized and glorified a life of struggle, illness, and addiction. To tell the story of Siddall, one must acknowledge both her art and that of the Brotherhood.

The Pre-Raphaelite Movement

The Pre-Raphaelite movement, started in 1848, was a rebellion against the traditional stylings of the convention of the Royal Academy of Arts. The Pre-Raphaelite movement’s members included artists and poets Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais (1829–1896), William Holman Hunt (1827–1910), Thomas Woolner (1825–1892), Frederic Stephens (1827–1907), and William Michael Rossetti (1829–1919). These men revolted against the style of art typified by Renaissance master and painter Raphael and wished to return to the art that preceded him, hence the name Pre-Raphaelite. Pre-Raphaelite art was inspired by Gothic and late-medieval art.[1] Consequently, Pre-Raphaelite artists opted for a return to naturalism; William Rossetti outlined the movement’s aims to “study Nature attentively…to sympathize with what is direct and serious and heartfelt in previous art, to the exclusion of what is conventional and self-parading and learned by rote.’”[2] These motives were spurred by a desire to create art for art’s sake. Returning to nature and leaving behind the Renaissance style was a departure from what the Pre-Raphaelites saw as stale conventions of techniques and subject matter for creating art. At its conception, this group of young men, the oldest being only twenty-four, believed they were revolutionizing the art world through their rejection of norms and the creation of a new art form.[3] The Pre-Raphaelite Brothers were not apolitical or atheist in their approach to rebellion. However, what set them apart from artists of the Renaissance was that their aesthetic approach was itself a form of political and social critique. They often followed religious themes and used subjects from religious texts as well as literature and poetry to explore social problems—but their approach to artistry was a critique of traditional and repetitive conventions and themes. To emphasize nature and realism in the subjects of their art, the Pre-Raphaelite Brothers often used the female body to create art that accentuated ideal beauty, femininity, love, and eroticism, whether in portraiture or poetry. In doing so, the Pre-Raphaelite Brothers often portrayed women as languid and nameless beauties.[4] One of the most famous of these beauties was Elizabeth Siddall, the longtime partner of Pre-Raphaelite Brother Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

Siddall’s Discovery

Rossetti and Siddall, the artist and his muse. Siddall is the unidentified beauty who looks out from his canvases, playing characters for him to depict in his art. Siddall is not just Rossetti’s muse, but an artist herself. She looks out from her own canvases and poetry to tell her own story. She details her struggles and her tumultuous relationship with Rossetti. Rossetti, second born and first son of four siblings, came from a family of unmatched artistic talent. His sister Christina Rossetti (1830–1894) was a poet, and his brother William Rossetti was a writer, critic, editor, and Pre-Raphaelite Brother. It was known that “few Victorian families were as gifted as the Rossetti’s.”[5] They were educated at home by their mother and encouraged to pursue the arts by their scholar and poet father. According to a biography of Rossetti by Pre-Raphaelite scholar Glenn Everett, “in 1846 [Rossetti] was accepted into the Royal Academy but was there only a year before he became dissatisfied and left.”[6] Then, in 1848, Rossetti went on to be a founding member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. As for his long-standing partner, Siddall, little is known surrounding her life. No diaries and few letters remained after her death.[7] New information and interpretations of primary sources have rewritten the narrative of this young woman’s life. For a long while, Siddall was memorialized through Rossetti’s art and poetry; he and the other Pre-Raphaelites were left to tell her story. As in her life, they gained full autonomy over her after death. However, now with increased interest in nineteenth century women and their rights and voices, Siddall has had a revival with increased interest in her poetry and art and what they have to say about her life and relationships. Jan Marsh, an authority on the Pre-Raphaelite circle, says that Siddall “received an ordinary education comfortable with her condition in life and became an apprentice at a bonnet shop in Cranborne Alley.”[8] During this time at the hat shop, details of Siddall’s early life are muddled.

Early scholars of the Pre-Raphaelites believed it was in this shop that Siddall was “discovered” for her beauty by artist and friend of the Pre-Raphaelites, Walter Deverall (1827–1854). Hereafter, she agreed to sit for him in his studio, where she eventually met Rossetti.[9] However, modern scholars believe Siddall was introduced to the Deverall family to assist the women of the house during dress fittings. Walter’s father being the head of the School of Design, and the junior Deverall being an artist and friend of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. According to an obituary published in the Sheffield Telegraph, “Miss Siddal showed some outlines and designs of her own leisure hours, to the elder artist Mr. D—and he, much pleased with them, introduced them to Mr. D—Jnr and the other young artists.”[10] This obituary would indicate that Rossetti and his Brothers had less of a hand in Siddall’s artistic beginnings than previously thought. They were exposed to her art through Deverall before she began modeling. It could be that Siddall began to model for the Pre-Raphaelites so as to get closer to the art scene, gain some formal training, and make her work known.

Upon her “discovery,” Siddall modeled for Deverall, Hunt, and Millais. The occupation of modeling was not respectable and was frowned upon for its assumed promiscuity—a lady posing and traipsing around the studios of various young men. Due to this stigma and Siddall’s common background, the Pre-Raphaelites made efforts to polish her. Siddall is often seen with the spelling “Siddal;” Emily Orlando, an esteemed scholar of Victorian Era literature, believes the Pre-Raphaelites purposefully misspelled her name, dropping the “l,” “to render the name more refined.”[11] This also rendered Siddall unable to exist outside of their circle; the face and figure that the Pre-Raphaelites made famous were attached to the spelling of the name Siddal. It is not only her name that was stripped of its commonness; the Brothers were known to repaint Siddall’s features to give them a nobler effect.[12] Marsh writes, “Elizabeth Siddal was regarded as a useful but not beautiful model, willing to wear costumes and hold difficult poses.”[13] Of the most challenging poses was Millais’ Ophelia, a display of art for art’s sake, no matter the consequences.

Figure 1: Sir John Everett Millais, Ophelia. Presented by Sir Henry Tate 1894, Photo: Tate

Ophelia would have a profound impact on Siddall’s life. At 19, Siddal posed as Hamlet’s drowning Ophelia, a character who, ironically, dies of grief and madness. To create the painting and the effect of Siddall in the river, Millais posed Siddall in a bath full of water. Unfortunately, the water grew cold, and Siddall, left to sit in the bath, grew very ill. This incident led to a long battle with chronic illness for Siddall. It was only a week before the posing that her brother had died of a chronic sickness.[14] Siddall’s poem “A Year and a Day,” possibly written about her experience modeling Ophelia, includes imagery of tall grass green leaves, all of which welcome Ophelia in her watery death. Siddall wrote:

“Dim phantoms of an unknown ill

Float through my tired brain;

The unformed visions of my life

Pass by in a ghostly train”[15]

Writing in retrospect, Siddall anticipates the illness she will contract. The visions of what her life could have been had she not been left to sit in that water pass her by. Millais’ Ophelia and the story surrounding the model and her connection to the character portrayed display the Pre-Raphaelite’s glorification and beautification of a dying woman. This art for art’s sake, eroticizes the death of Ophelia and the grief and madness which led her there and neglects the toll art takes on Siddall, writing her off as the nameless model.

The Beginning of Rossetti and Siddall

It was after this incident that Siddall began sitting exclusively for Rossetti. To Rossetti, “Lizzie” was a model and student of the arts. Art Historian Laurel Bradley wrote, “he cherished her drawings, proudly displaying them to friends who visited the studio.”[16] Siddall became a private pupil of Rossetti’s. She roused his interest in her art and inspired his sympathy for her inability to attend and afford classes. By 1854, Rossetti’s infatuation with Siddall was evident. According to Marsh, “Rossetti’s love is clearly visible in in his drawings of Lizzie. They depict, amongst other things, the change from that of model to friend and beloved.”[17] Rossetti and Siddall spent long hours together as he drew her. Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s sister and fellow artist Christina Rossetti wrote her poem “In an Artist’s Studio” about the relationship between an artist and their muse. This poem, dated 1856, was supposedly written after Rossetti visited her brother’s apartment and saw it littered with sketches of Siddall. However, she felt all the illustrations lacked Siddall’s physical presence, showing the gap between male artists and their female muses.[18] As a single woman whose art remained in the shadow of her brothers while she was alive, her poetry depicts the frustration of a scorned woman. Christina Rossetti sees the betrayal of men against women and the unrealistic standards placed on women by their spouses and lovers. In “In an Artist’s Studio,” Rossetti wrote, “One face looks out from all his canvasses… Not as she is but was when hope shone bright; / Not as she is, but as she fills his dream.”[19] Rossetti’s portraits of Siddall blur the lines between reality and imagination. He has pictures of her walking, standing, sitting, reading, and painting. He has her captured in every pose, feeding off of her face for his art, using her for his gain, and in the process, stripping her of her own autonomy. Siddall was an object, a blank slate on to which he could project his dreams and fantasies. He presents art as the act of consumption, consuming her external appearances and regurgitating it onto his canvas as though they represent her actual being and soul. He shows her not as she truly is, but as he sees her, he sees Siddall as an idyllic woman who owes herself to him.

Siddall and Her Art

Siddall, like Dante Rossetti, was not only a talented artist but also a poet. In her poem “The Lust of the Eyes,” the reader hears a man’s voice, presumably an artist describing his muse. Siddall encapsulates how it feels for a woman to be loved for nothing more than her beauty. In this poem, Siddall wrote:

“Low I sit at my Lady’s feet

Gazing through her wild eyes

Smiling to think how my love will fleet

When their starlike beauty dies.”[20]

Although Siddall was a woman of exceptional talent, she recognized that men may only appreciate and love her for her physical beauty. This was a harsh reality for many women of the Victorian era. The man that Siddall describes smiles at the idea of his love fading away with his lover’s beauty. His love cannot stand the test of time because he does not love the timelessness of her talent and soul, only the superficial aspects of her. He completely disregards her as a whole person. This male voice has no sympathy for his lover. On the contrary, he is purely selfish and misogynistic; she will be of no importance to him when she loses her societal influences of beauty and youth. It is hard not to conclude that Siddall drew upon her personal experiences with Rossetti and other Pre-Raphaelite men to write this poem. According to Mariana Cunha, Rossetti’s brother William remarked, in a rather backhanded compliment, that “without overrating [Siddall’s] actual performances in either painting or poetry, one must fairly pronounce her to have been a woman of unusual capacities…”[21] During the Victorian era, women were valued for their beauty and domestic abilities. The right to genius and talent was reserved for men. William is saying that Siddall is uniquely talented for a woman but is obviously inferior in comparison to men; her talent is not even comparable.

The Decline of Siddall

By 1857, Rossetti and Siddall’s relationship deteriorated. According to Bradley, while rumors of an almost decade-long on-and-off engagement circulated, “the painter’s exclusive love for Siddall abated by 1856, when he entered into a liaison with Annie Miller.”[22] Cast aside, Siddall returned to her hometown to study art. By 1860, Siddall had grown gravely ill. It is rumored that her family and former patron John Ruskin (1819-1900) appealed to Rossetti who, after hearing of her ill health, rushed to her and nursed her back to health, keeping his promise of marriage when she returned to better spirits. They were married in the spring of the very same year. Siddall’s poem “Worn Out” bears witness to a lover experiencing the tension of wanting their partner to stay but nevertheless asking them to go. She wrote, “I cannot give to thee the love / I gave so long ago.”[23] This poem can be analyzed in the context of Siddall’s relationship with Rossetti. She is no longer able to love Rossetti as she used to because of the illness which prevents her from living a full life. In the poem, she wishes her lover would leave so that he can save himself from her inevitable demise. Siddall continued to suffer from mental and physical ailments, and, two years after her marriage to Rossetti, she experienced a stillbirth and passed away from a laudanum overdose shortly after. Much like Ophelia, Siddall died of grief and madness.

Figure 2: Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Beata Beatrix. Oil on canvas, 1871/1872. Art Institute of Chicago.

Rossetti began his painting Beata Beatrix before the passing of his late wife, using her as his model. The painting was finished in 1864 after Siddall’s death and depicts Beatrice Portinari from Dante Alighieri’s (1265–1321) poem “La Vita Nuova” at the moment of her death. This painting is meant to be an homage to Siddall. However, according to Mariana Bicudo Castelo Branco Cunha, a scholar of Pre-Raphaelite women, “Elizabeth’s poor health speaks to the gender bias of the time... Because a woman’s state of illness makes man the savior... he is seen as the much-needed strong and caring by-stander.”[24] Although Beata Beatrix does not display Siddall on her death bead, it still romanticizes her illness. Rossetti continued to feed upon her face even as she struggled both physically and mentally. He disregarded her ailments by portraying her in a trance or dream-like state. The rumors surrounding Beata Beatrix emphasize Rossetti’s disregard for Siddall’s wishes and his continued ownership of her likeness and autonomy even after death. When Siddall passed, Rossetti buried a series of his sonnets with her. Seven years later, in 1869, he exhumed her body to retrieve the poems and publish them for a profit.[25] Beata Beatrix was not finished until 1870, after the exhumation of Siddall’s body. Orlando writes of an unfortunate rumor, that, after retrieving his sonnets, Rossetti “propped up Lizzie’s corpse on her death bed while he painted Beata Beatrix.”[26] A rumor, rooted in male artists’ obsession with the death of a woman, more specifically, a beautiful woman. Male Victorian artists and patrons of the arts were obsessed with ill-looking and dying women, stemming from their desire to control women.[27] By romanticizing the distressed damsel archetype, these men asserted their dominance over women. Rossetti could no longer save the distressed damsel, but he could still control her.

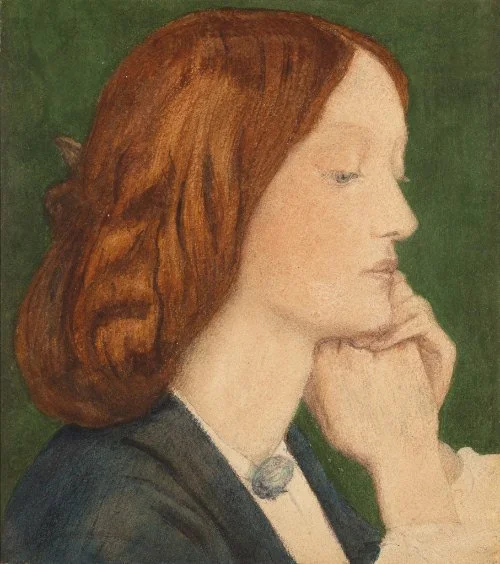

Figure 3: Elizabeth Siddall, 1829-1862. Elizabeth Siddall: Self-Portrait, 1853-1854. Rossetti Archives.

Figure 4: Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1828-1882. Elizabeth Siddal. Graphite and watercolor on paper, 1854. Delaware Art Museum.

Siddall, an artist in her own right, was not appreciated until after her death. Her poems and paintings often contradicted those of the men she served as a muse to. The portraits of Siddall created by the Brothers are not an invitation into her private life, but an invitation into these men’s perception of their muse; they give the viewer the ability to see her as they do, the epitome of Pre-Raphaelite beauty standards and perfection. Siddall’s self-portrait is the first time she is shown through her own lens rather than the male gaze of Pre-Raphaelite ideals. Siddall’s self-portrait is especially interesting because it challenges the narrative of the idyllic Victorian woman. In her portrait, she is not Rossetti’s dream; she is not his Shakespearean heroine or his beautiful dead girl. She presents herself simply. In Rossetti’s art, Siddall typically looks away, not directly at the viewer. Siddall looks directly at the viewer in her self-portrait, and her eyes are dark and emotionless as she gazes off. The picture feels dark and ominous; there is no movement or activity as there usually is in Rossetti’s portraits. On the other side of the easel, as the artist and not the muse, Siddall was able to move beyond the superficial depiction of women in the Victorian Era. Siddall painted herself as she genuinely was in her self-portrait, all sharp features, heavy lids, and a frown saturated in dark colors, contrasting with how the Pre-Raphaelite men chose to depict her.

Scholar Serena Trowbridge wrote, “none of Siddall's poems were published during her lifetime, and most only exist in draft form, often difficult to read.”[28] However, while she was alive, four of Siddall's works were included in a small exhibit of Pre-Raphaelite art and included in the subsequent British Art exhibition, which toured America in 1857.[29] According to Marsh, Siddal displayed “an unconventional female determination to be an artist, in opposition to parental wishes.”[30] In the mid to late 19th century, it was difficult and uncommon for a woman to be a professional artist. Professional art training, such as through the Royal Academy of Art, was reserved solely for men. To be an artist was not a suitable profession for a woman. Siddall's ability to have her art shown in exhibitions is a testament to her talent and perseverance. While Siddall would not have had the exposure that she did without Rossetti and the other Pre-Raphaelite Brothers, she does not owe them for her success.

Conclusion

The tragic arc of Siddall’s life, marked by illness, unfulfilled love, and her untimely death, mirrors the themes of many Pre-Raphaelite works, yet her legacy is not solely one of tragedy. Initially known only as Rossetti’s muse and lover, Siddall was able to emerge through this complex relationship as an artist and poet of significant talent and vision in her own right. In her defiance of Victorian conventions and her insistence on pursuing her art despite the obstacle, Siddall carved a space for herself and other women throughout the history of art.

The posthumous recognition of Siddall’s talents and the reevaluation of her contributions to the Pre-Raphaelite movement reflects a broader reassessment of the roles and representation of women in art history. While Rossetti’s depiction of Siddall and the narratives that surround their relationship often relegate her to the role of muse, a deeper examination reveals a woman of profound artistic and poetic ability, whose influence extends beyond her physical presence in Rossetti’s work. There is a growing desire and willingness to sever Siddall's life and art from those of the men who controlled her autonomy. To do this would rid Siddall's art of its own context. As displayed, her close relations with these men created inspiration and art. Her narrative cannot be disentangled from theirs; it can only be rewritten with her as the heroine rather than the damsel in distress. Siddall exemplifies the challenges faced by women artists in asserting their autonomy and talent, and the enduring power of their art to transcend the circumstances of its creation. Siddall’s work challenges viewers to look beyond the surface and recognize the often over-looked voices and inner lives of women.

Notes

[1] Emily Orlando, “‘That I May Not Faint, or Die, or Swoon’: Reviving Pre-Raphaelite Women,” Women’s Studies 38, no. 6 (September 2009): 617.

[2] Heather Bozant Witcher and Amy Kahrmann Huseby, “Introduction: Defining Pre-Raphaelite Poetics,” In Defining Pre-Raphaelite Poetics, edited by Heather Bozant Witcher and Amy Kahrmann Huseby, (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2020), 1.

[3] Witcher and Huseby, “Introduction: Defining Pre-Raphaelite Poetics,” 8.

[4] Orlando, “‘That I May Not Faint, or Die, or Swoon’: Reviving Pre-Raphaelite Women,” 616.

[5] “Dante Gabriel Rossetti,” Poetry Foundation, accessed February 18, 2024.

[6] Glenn Everett, “Dante Gabriel Rossetti—Biography,” Accessed February 9, 2024.

[7] Serena Trowbridge, “Introduction,” in My Lady’s Soul: The Poems of Elizabeth Siddall (Brighton: Victorian Secrets Limited, 2018), 9.

[8] Jan Marsh, The Legend of Elizabeth Siddal (Quartet Books, 1992), 58.

[9] Orlando, “‘That I May Not Faint, or Die, or Swoon’: Reviving Pre-Raphaelite Women,” 626.

[10] Marsh, The Legend of Elizabeth Siddal, 157.

[11] Orlando, “‘That I May Not Faint, or Die, or Swoon’: Reviving Pre-Raphaelite Women,” 629.

[12] Marsh, The Legend of Elizabeth Siddal, 162

[13] Marsh, The Legend of Elizabeth Siddal, 162

[14] Marsh, The Legend of Elizabeth Siddal, 163

[15] Elizabeth Siddall, “A Year and a Day.” Representative Poetry Online, University of Toronto.

[16] Laurel Bradley, “Elizabeth Siddal: Drawn into the Pre-Raphaelite Circle,” Museum Studies 18, no. 2 (1992): 139.

[17] Marsh, The Legend of Elizabeth Siddal, 168

[18] Mariana Bicudo Castelo Branco Cunha, “‘Behind Those Screens’—Bringing Women Forth: Christina Rossetti and Elizabeth Siddal” 17, no. 1 (January 14, 2020): 7.

[19] Christina Rossetti, “In an Artist’s Studio,” Poetry Foundation, accessed February 8, 2024, lines 1 and 13-14.

[20] Elizabeth Siddall, “The Lust of the Eyes.” Representative Poetry Online, University of Toronto Libraries, 5-8.

[21] Cunha, “‘Behind Those Screens,’” 3.

[22] Bradley, “Elizabeth Siddal: Drawn into the Pre-Raphaelite Circle.” 141.

[23] Elizabeth Siddall, “Worn Out.” Representative Poetry Online, University of Toronto Libraries, 9-10.

[24] Cunha, “‘Behind Those Screens,’” 4.

[25] Bradley, “Elizabeth Siddal: Drawn into the Pre-Raphaelite Circle,” 142.

[26] Orlando, “‘That I May Not Faint, or Die, or Swoon’: Reviving Pre-Raphaelite Women,” 622.

[27] Orlando, “‘That I May Not Faint, or Die, or Swoon’: Reviving Pre-Raphaelite Women,” 615.

[28] Serena Trowbridge, “Introduction.” In My Ladys Soul: The Poems of Elizabeth Eleanor Siddall, (Brighton: Victorian Secrets Limited, 2018), 18.

[29] Trowbridge, “Introduction,” 10.

[30] Marsh, The Legend of Elizabeth Siddal, 165.

Lauren Flagg

Lauren Flagg is a Senior at Fairfield University studying Politics, English: Professional Writing, American Studies, and Communication. She enjoys conducting research that focuses on women’s rights, and as a Corrigan Scholar at Fairfield, she authored research on the Supreme Court decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. Upon graduation, she hopes to work in the public policy or legislative sphere, where she can bring her passion for women’s rights.