La Fornarina: A Beautiful Woman, the Myth of the Artist and the Muse

Fornarina: C'était une belle femme; inutile d'en savoir plus long.[1]

(“Fornarina. She was a beautiful woman. That is all you need to know”)

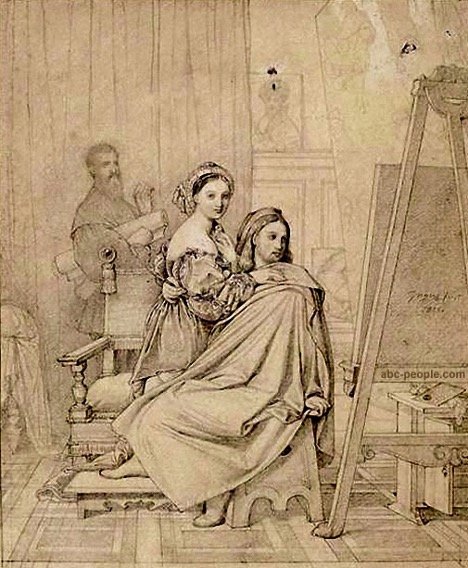

Two lovers are locked in an embrace. The woman folds her swan like neck over her lover, the weight of her body rests atop his. And yet the man appears strangely distracted. He looks away from her, toward a framed painting to his left —a portrait he made of the same woman, still in its early stages. In Raphael and La Fornarina (Fig. 1), Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres depicts the artist he seeks to emulate the most —Raphael —with his muse, the Fornarina, on his lap. The master and the model become reduced to actors with rigid roles to play: the irresistible seductress and the powerlessly, although distractedly, seduced. And while it is commonly assumed that Raphael was the greatest source of inspiration for Ingres, in this essay I will argue that he is most inspired not by Raphael directly, but by Giorgio Vasari’s fictional retelling of an aestheticized life of an artist who tragically perished from the excess of lovemaking. Through the depiction of the Fornarina in this image and the many versions he made of this painting, Ingres takes that fictional retelling as his starting point and attempts to write his own, more perfect story.

Fig. 1 Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Raphael and La Fornarina, 1814, oil on canvas, 64.8 x 53.5. Harvard Art Museum, Boston.

1. Ingres’s Raphael and La Fornarina

Separating the facts from the mythos surrounding her role in Raphael’s story, although challenging, provides a clue to understanding her life. Scholars identified her as Margarita Luti: “it has now been ascertained from a census return made under Leo X. in 1518, that one of the houses of the Sassi family was occupied by the baker Francesco from Siena.”[2] After all, Margarita was indeed a baker’s daughter. In Ingres’s painting, the Fornarina wears a delicate dress with a low neckline, exposing her sensuously arched neck and back. In the later versions of this painting (Fig. 2–3), where the Fornarina leans over Raphael even more, Ingres further accentuates her role as a seductress, which is established in this version.[3] From first glance, Fornarina’s identity becomes entangled in her portrayal as an object of sexual desire. Framing the two lovers are two paintings by Raphael that the Fornarina allegedly modeled for: Madonna Della Sedia (Fig. 4) against the back wall, and a portrait now known simply as La Fornarina (Fig. 5), towards where the artist directs his gaze. [4]

Left Image: Fig. 2 Ingres, Raphael and La Fornarina, 1827, oil on canvas, private collection, New York.

Right Image: Fig. 3 Ingres, Study for "Raphael and the Fornarina", 1825, pencil on paper, Louvre Museum, Paris

Left Image: Fig. 4 Raphael, Madonna Della Sedia, c. 1513-1514, oil on canvas, 71 cm × 71 cm, Palazzo Pitti, Florence.

Right Image: Fig. 5 Raphael, La Fornarina, 1518-1519, oil on wood, 85 cm × 60 cm, Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica, Rome.

The lion’s foot of the easel in the lower right corner of the painting echoes the twist of Raphael’s own red boot. Raphael’s stretched-out black coat resembling a canvas further emphasizes this equating of the artist with the easel. As he hugs the Fornarina, he still holds up a brush — the act of lovemaking and the act of painting intertwined into one. He wears a black coat draped in a straight line that covers most of his body. The left side of his face appears shaded as he looks away from us. By concealing Raphael, Ingres reveals the true subject of the painting —the Fornarina and her beauty.

But it is not the Fornarina, the lover in his arms, Raphael is interested in. Instead, he looks directly at the canvas in progress behind him. Art historian Rosalind Krauss argues that “the artist embraces what he does not look at. Ingres' Raphael has eyes only for what is on his easel, which is to say, the model in representation. […] The Fornarina is held only after she has been beheld in what Ingres himself depicts.”[5] Thus Raphael’s enrapture by Fornarina’s portrait behind him paradoxically means that he is not attending to her physical presence on his lap at all. Her identity is reduced to being a subject of depiction.

Nor does the Fornarina look at her lover. Instead, she gazes directly at the viewer, which emphasizes her dominant role in this painting over that of Raphael. While Raphael looks at Fornarina’s portrait behind him, we inadvertently mirror his actions by meeting the gaze of the woman in the painting. Just like Raphael establishes an emotional connection with Fornarina’s image on his canvas, the spectator viewing this painting is forced to do the same, creating layers of pictorial representations stacking on top of each other.

Yet Ingres’s Fornarina appears much more akin to the paintings around her rather than to a “real” woman. The exquisitely drawn folds in her dress seem to be taken directly from an academic exercise on depicting fabric. The pose of the couple is perfectly constructed, every object in the painting is placed just so, in Raphaelesque harmony. Her features idealized, the Fornarina is identified with both sides of femininity (as Raphael’s contemporaries would have seen it then) —the nude La Fornarina on the right and Madonna Della Sedia behind them —the Madonna and the whore. As Wendy Leeks argues, “The figure is mistress, the object of sexual desire and equivalent of the odalisque, and at the same time Virgin, the chaste being without sexuality who is also mother. […] The virgin and the odalisque are not merely sisters, they are one.”[6]

The Fornarina on Raphael’s knees, La Fornarina in the painting on the easel, and Madonna Della Sedia in the background—all three women look back directly at the viewer, spectacles to be consumed by the gaze. This is the only way we can see her —as a subject of a painting, a merging of multiple heroines created by Raphael, not a real person. Her legs invisible, the weight of her body propped up by Raphael’s embrace —she could be a puppet he holds up. The way he embraces her while still holding up a brush declares that her identity is all his creation, entirely in his hands. We see her the way Raphael sees her in his mind’s eye, even when turned away from her.

Hence, to revise my earlier statement, the true subject of this work is not the Fornarina herself, but her representation. We are in a painting about painting —the blank wall behind the two figures creates a frame around them, and the entire room turns into a canvas. A doubling emerges —it is both Ingres’s canvas and Raphael’s. The viewers see the world as Ingres would see it – the Fornarina placed against the canvas-wall behind her becomes a painting to be completed. The only glimpse of the outer world becomes theatrically unveiled by a curtain on the upper left. Or is it the opposite, the room-painting being theatrically revealed to the world by the opening curtain? Even in attempting to describe this painting, the language runs into a dead end. It seems impossible to refer simply to the Fornarina, because the question immediately arises —which one? As I stand in front of her, I am unsure which of her identities I see —the Fornarina embracing Raphael in Ingres’s painting, La Fornarina the painting by Raphael, La Fornarina copied within Ingres’s painting, the Fornarina in Madonna Della Sedia both by Raphael and here in Ingres’s version of Raphael, or, finally, Fornarina the “real” woman herself? The many versions of her across multiple canvases mirror one another.

2. Margarita Luti and the myth of the Fornarina

To establish the truth of who the Fornarina really was, it is worth briefly stepping away from Ingres to focus on the known biographical evidence of her life. The story of Raphael and the Fornarina was described in dozens of versions by dozens of authors throughout the last half a millennium. The most integral of such retellings is Giorgio Vasari’s Le Vite de' più eccellenti pittori, scultori, ed architettori.[7] This fundamental art historical text published in 1550 is the first to paint a verbal portrait of the Fornarina. But even then, most mentions of La Fornarina in Vasari already skip the biographical facts in favor of focusing on her role as a muse. In his description of Raphael’s La Donna Velata (Fig. 6), Vasari writes that the model is a woman "whom he loved until he died, and of whom he made a most beautiful portrait, which seems spirited and alive." In the first edition, Vasari never even mentions her name. He only introduces her to the reader when he expands on the same passage in the appendix to the second edition: “portrait of Margarita, Raphael’s mistress… Margarita.”[8] Elsewhere in the text Vasari effectively blamed her for Raphael’s death from an excess of lovemaking: “Raffaello continued to divert himself beyond measures with the pleasures of love; whence it happened that, having on one occasion indulged in more than his usual excess, he returned to his house in a violent fever.”[9] And thus the myth of the temptress Fornarina who drove Raphael to his death is born.

Fig. 6 Raphael, Lady with a veil (La velata), c. 1516, oil on canvas, 82 cm × 60.5 cm, Palazzo Pitti, Florence.

Vasari was not the only one who was less interested in Margarita’s life than in her identity as a muse. Even the modern scholarship on the subject focuses more on the symbolic meaning of her representation rather than biographical data. Art historian Giuliano Pisani argued that calling a woman a fornarina stems from antiquity, specifically from when the Greek poet Anacreon addressed his poetry to la fornarina as early as in the sixth century BCE. Pisani writes that translating la fornarina only as a literal “baker” misses an alternative meaning. The Italian word forno (“oven”) can also metaphorically refer to the female sexual organs, and by extension, to the woman as a prostitute.[10] That portrayal certainly fits Vasari’s creation, but does it match the biographical facts that are known about this woman?

Clear documentation of her life appears in a ledger of the Congregation of Sant’Apollonia in Trastevere, “a kind of home for fallen and repentant women.”[11] According to that entry “the widow Margarita, daughter of the late Francesco Luti of Siena”[12] entered the establishment on August 18, 1520, or only four months after Raphael’s death. Vasari details that Margarita was with Raphael until the moment of his death when the Pope’s messenger removed her from the room because they were not legally married, and that Raphael “left her with a sufficient provision wherewith she might live in decency.”[13]

Despite evidence supporting the contrary, everyone from Vasari to Ingres to contemporary scholars, such as Pisani, continue to cast her as a prostitute. But perhaps even the myths of Margarita Luti’s life reveal something about representations of women in visual culture, sometimes more so than reality. In fact, soon after her death, she becomes a tool for telling any story about Raphael’s life a particular narrator wanted to tell —the myth of her being a prostitute serves as a prominent example of such fictional narratives.

Ingres contributes to the myth of prostitution by making the seductress Fornarina more present in his painting than her other personas. The primary subject of Raphael’s gaze is the enchantress La Fornarina, rather than the maternal Madonna Della Sedia hidden in the background. This emphasis speaks to the fact that her identity is that of his lover first, and a nurturing mother second, at least in Ingres’s story. This contrast between the temptress Fornarina and the powerlessly seduced Raphael inadvertently sets up the stage for Ingres’s identification with the Renaissance master. Krauss argues that Ingres saw himself as “overpowered” by Nature’s “irresistible ascendancy.” Charles Baudelaire also described the artist as "thus smitten with an ideal which is an enticingly adulterous union between Raphael's calm solidity and the gewgaws of a petite-maîtresse,”[14] which could just as easily serve as ekphrasis for the Harvard painting. Thus, in portraying Raphael as the passive party, subject to Fornarina’s inescapable charm, Ingres draws a parallel between his perception of the Renaissance master and his own self-identification.

Just like Ingres appropriates the Fornarina to paint himself as the powerlessly seduced, the Fornarina became a narrative device to serve any given author’s purpose in retelling Raphael’s story. Marie Lathers argues that “each aesthetic era had reassessed Raphael and repeated and embellished the Raphael-Fornarina myth to fit the expectations of contemporary generations. […] Ingres’s identification with and mourning of Raphael is a primary example of this revival.”[15] Anthony Blunt goes even further in arguing that Vasari “invented the legend of Raphael.”[16] Elsewhere Vasari implies that Raphael could not work unless his mistress was around him at all times: “[When he received a commission from Agostino Chigi], Raffaello was not able to give much attention to his work, on account of the love that he had for his mistress; at which Agostino […] [arranged] that this lady should come to live continually with Raffaello in that part of the house where he was working; and in this manner the work was brought to completion.”[17] Later in the text, Vasari goes further to portray the Fornarina not just as the muse but as a metaphor for painting itself. [18] He writes “when this noble craftsman died, the art of painting might well have died also, seeing that when he closed his eyes, she was left as it were blind.”[19] With this passage Vasari, just like Raphael before him, turns Margarita Luti from a baker’s daughter into La Fornarina, the ideal and the myth.

3. Ingres and the myth of Raphael and the Fornarina

The environment in which Ingres first encountered the myth of Raphael’s life shaped the way he saw Raphael’s muse. Early in the nineteenth century, Ingres was swept away by the wave of society’s renewed interest in the High Renaissance. And for Ingres, the most inspiring of all Renaissance masters was Raphael. His respect and imitation turned into idolatry when he begged the pope for a part of a bone from Raphael’s body when his remains were repatriated, to which the pope conceded.[20] What Ingres knew of Raphael he learned through his paintings and the critical discourse on the painter, the most authoritative source still being Vasari’s Le Vite. Hence, Ingres does not attempt to paint a scene that factually happened, but rather the myth created by Raphael’s oeuvre and the romanticized image created by Le Vite. Indeed, Raphael and La Fornarina could serve as an illustration to Vasari’s retelling of the life of this “very amorous man.”[21] Inspired by Vasari’s emphasis on Raphael’s search for perfect beauty, Ingres makes a Raphaelesque painting of his own —the Harvard painting is a highly idealized work, which places a thought-out disegno above the realism of the scene. “Ingres believed that art —his art, painting —had reached its height with Raphael and that the moral artist could only strive for more perfect imitations of the master,”[22] argued Marie Lathers. And that “more perfect imitation” is key to understanding Ingres’s ambitions in repeatedly recreating the many versions of this painting.

Thus, Ingres mythologizes not just the Fornarina, but Raphael as well. The master’s identity becomes a symbol, something greater than himself. The Renaissance master and the Fornarina together become stand-ins for the archetypal relationship of the artist and the muse. The two lovers play roles Ingres assigned to them: while the Fornarina plays the coquette, Raphael serves as the epitome of the tender nobility and harmony that Ingres always reserved for depictions of him.[23] An attentive student of Raphael’s style, Ingres idealizes not only the master’s muse but also the master himself and the relationship between the two. Yet Ingres does not stop at purely imitating the great master —he starts to embellish the story. As previously mentioned, Ingres associates himself with Raphael by establishing the dichotomy of the Fornarina/Nature as the active beguiling force, and Raphael/himself as the defenselessly seduced. But the self-identification goes even further. On Fornarina’s finger, Ingres prophetically places a ring, metaphorically wedding her himself.[24] Since Raphael and the Fornarina were never married, the ring comes to symbolize Ingres’s attempt to outdo the master and adopt Raphael’s muse as his own. This detail sets the tone for Ingres’s self-identification with Raphael, which continues through the rest of his life.

He places two of Raphael’s paintings in Raphael and La Fornarina, thereby making his own copies of Raphael’s originals and paying homage to the master. But he goes even further in his attempt to surpass his idol, for the Fornarina in the middle of this painting is that of Ingres’s creation, not Raphael’s. What better way to eclipse his master than by depicting her in an even more perfect, more Raphaelesque way?

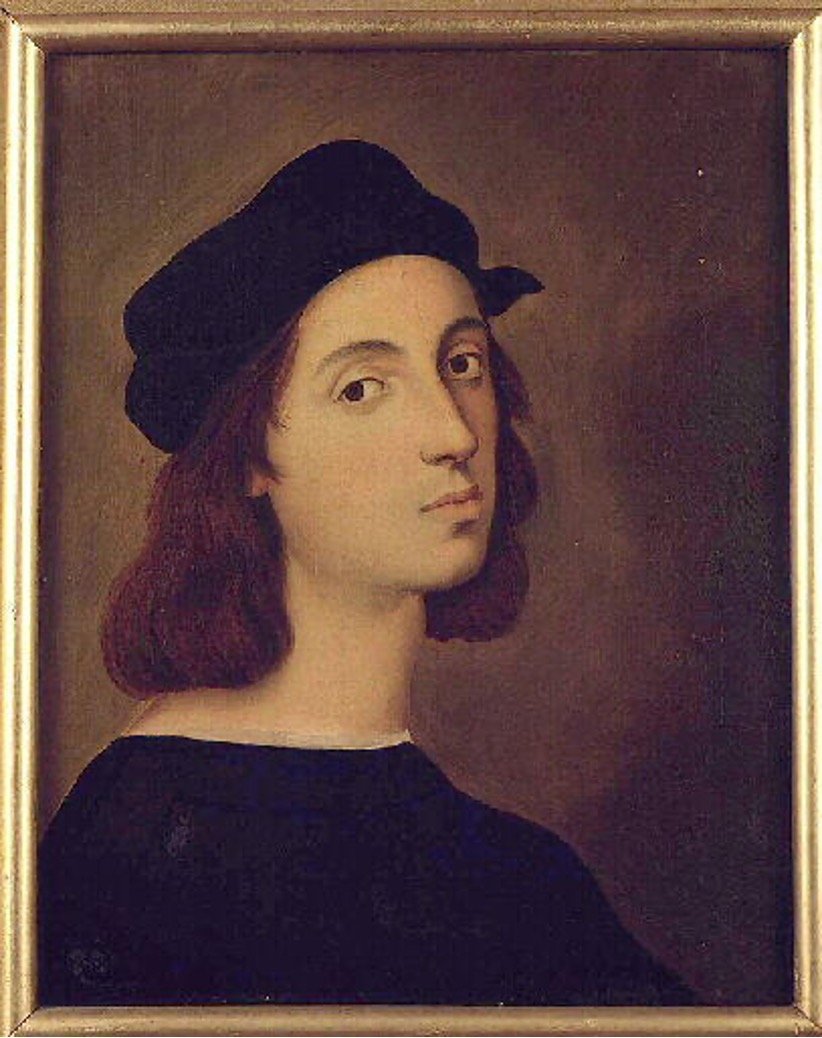

Raphael in the painting may hold her in his hands, but it is Ingres who paints her this time. “If Ingres identifies himself with the son in the Madonna Della Sedia and with the artist/lover/son in the Raphael and the Fornarina series and thus projects himself in unconscious fantasy into the mother and child relationship, he returns to a moment of dual-unity,”[25] argues Leeks. This duality evolves further when a decade later, Ingres copies Raphael’s Self-portrait (Fig. 7–8), effectively taking on Raphael’s image as his own. Multiple doublings are at work in Raphael and La Fornarina —Margarita as both the mother and a lover, and Ingres as both himself and Raphael. It appears significant that despite preparing an entire series of paintings on Raphael’s life, the only paintings of this project he managed to realize depicted Raphael’s romantic pursuits, and the time of their completion coincides with Ingres’s own engagement and marriage.[26] Ingres saw the master’s life as a blueprint for his own. This master plan stayed with Ingres throughout his entire life, adapting and evolving as his own self-perception changed over time. Forty-six years after completing the Harvard painting, in 1860, Ingres picks up the brush again: “I am taking up again the picture of Raphael and La Fornarina, my last edition of this subject, which will, I hope, cause the others to be forgotten.”[27] According to the art historian Krauss, in that desire for the definitive, perfect version lies the key to understanding the many layers of repetition involved, which she calls “The Pursuit of Perfection.”[28]

Left Image: Fig. 7 Ingres, Portrait of Raphael, 1820-1824, oil on canvas, Musée Ingres, Montauban.

Right Image: Fig. 8 Raphael, Self -portrait, 1504-1506, oil on board, 47.5 cm × 33 cm (18.7 in × 13 in), Uffizi, Florence.

The repetition occurs in this painting (the many representations of the Fornarina as part of arriving at the most perfect one in the middle), in the larger motif (the four versions of Raphael and La Fornarina, every consecutive one replacing the previous versions), and in Ingres’s oeuvre more generally (most of Ingres’s best-known works are serial: The Grand Odalisque, Paolo and Francesca, The Turkish Bath, among others). And if we were to follow Ingres’s logic of repetition as a path to perfection to its completion, then creating consecutive “versions” of Raphael’s paintings is not just self-effacing flattery. It is nothing less than an attempt to surpass his master, to replace Raphael’s originals with Ingres’s own, establishing his definitive place in history.

If Vasari is the creator of the myth surrounding Raphael and the Fornarina, Ingres is its heir and prophet. The stories of Raphael, the Fornarina, Ingres, and their very bodies become symbols, pointing to certain relationships between the artist and the muse, between the artist’s craft and his place in history.[29] In recreating Raphael’s muse over and over, Ingres attempts to construct an even more perfect example of the artist-muse relationship than the biographical facts of Raphael’s life could ever allow for. In that, Ingres demonstrates how an artist’s life —both Raphael’s and his own —can begin to symbolize the very ideals of aesthetic perfection that they attempted to depict in their paintings. By endlessly copying Raphael’s motif, Ingres writes himself into the narrative, in his attempt to outdo and replace Raphael. With each retelling, Ingres turns the story into a more perfect, definitive “edition of this subject,” idealizing his own life for posterity and hoping “to cause the others to be forgotten.”

Endnotes

[1] “Fornarina. She was a beautiful woman. That is all you need to know”- Gustave Flaubert, 1954. Dictionary of Accepted Ideas. Norfolk, Conn.: New Directions Books.

[2] Konody, Paul G. 1908. Raphael. New York: T.C. & E.C. Jack., 142.

[3] Ingres made six known versions of this painting as well as numerous drawings. The Harvard painting is the earliest known painting of this series.

[4] Lathers, Marie. Bodies of Art : French Literary Realism and the Artist's Model. 67.

[5] Krauss, Rosalind E. 1989. You Irreplaceable You in Studies in the History of Art , 1989, Vol. 20, Symposium Papers VII: RETAINING THE ORIGINAL: Multiple Originals, Copies, and Reproductions (1989), National Gallery of Art, 157

[6]Leeks, Wendy. 1986. “Ingres Other-Wise.” Oxford Art Journal 9 (1). https://doi.org/10.1093/oxartj/9.1.29, 33.

[7] Vasari, Giorgio, Betty Burroughs, and Jonathan Foster. 1946. Vasari's Lives of the Artists; Biographies of the Most Eminent Architects, Painters, and Sculptors of Italy. New York: Simon and Schuster.

[8] Vasari, Lives, 746.

[9] Vasari, Lives, 743.

[10] Giuliano Pisani. 2015. Le Veneri di Raffaello (tra Anacreonte e il Magnifico, il Sodoma e Tiziano, Ediart. Studi di Storia dell'Arte 26, 110.

[11] Konody, Paul G, Raphael, 142.

[12] Konody, Paul G, Raphael, 142.

[13] Vasari, Lives, 792.

[14] Krauss, You Irreplaceable You,153

[15] Lathers, Bodies of Art : French Literary Realism and the Artist's Model. 63.

[16] Blunt, Anthony. 1958. The Legend of Raphael in Italy and France. Maney publishing. 12.

[17] Vasari, Lives, 737-738.

[18] Fornarina also comes to stand for the representation of ideal beauty for the master “[Raphael gave] her dark, arched eyebrows, prominent eyes with dark irises, fine lines like necklaces forming rings around her neck, and delicately slender fingers gracefully parted, presenting his mistress to the world as the true mistress of his art, perfect beauty itself.” – Cropper, Elizabeth. 1976. On Beautiful Women, Parmigianino, "Petrarchismo", and the Vernacular Style. 391.

[19] Vasari, Lives, 748.

[20] Lathers, Marie. Bodies of Art: French literary realism and the artist’s model, 62.

[21] Vasari, Lives, 746. Baudelaire also noted Ingres’s idealization of his models: “De telles considérations ne sont pas assez familières aux portraitistes; et le grand défaut de M. Ingres, en particulier, est de vouloir imposer à chaque type qui pose sous son œil un perfectionnement plus ou moins despotique, emprunté au répertoire des idées classiques" (Considerations of this kind are not sufficiently familiar to our portrait-painters; the great failing of M.Ingres, in particular, is that he seeks to impose upon every type of sitter a more or less complete, by which I mean a more or less despotic form of perfection, borrowed from the repertory of classical ideas.") – Baudelaire, Charles. 1964. The Painter of Modern Life And Other Essays. New York: Phaidon Press.

[22] Lathers, Marie. Bodies of Art: French literary realism and the artist’s model, 65.

[23] Vigne, Ingres, 123.

[24] Thanks to radiography, modern historians found a ring on Raphael’s original La Fornarina that bears Raphael’s name, sparking conjectures that the two were secretly engaged. – Lathers, Marie. Bodies of Art : French Literary Realism and the Artist's Model. 67.

[25] Leeks, Wendy. Ingres Other-Wise, 35.

[26] Vigne, Georges., and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. 1995. Ingres. 1st ed. New York: Abbeville Press. 122.

[27] Ingres’s diary quoted in Krauss, You Irreplaceable You, 154

[28] Krauss, You Irreplaceable You, 154

[29] “Raphael’s death in 1520 at the age of thirty-seven was mourned as premature in most accounts. Ingres, on the other hand, lived an unusually long life, from 1780 to 1867. Whereas Raphael’s death was blamed on the excessive desire for his model, Ingres’s restrained relationship to the opposite sex – a group of ladies – was held responsible for his death. In art historical biography, Ingres’s desire was, then, a variation – however inverted – on that of his master: Ingres repainted Raphael and rewrote his myth by dying a chivalrous and virtuous death. In this way, “ Lathers, Marie. Bodies of Art, 79-80.

Author Bio

Daria Rose Evdokimova

is a senior at the college and an incoming PhD student at Harvard. Her focus is on the European late Medieval period and she is interested in exploring what artworks can reveal about being human.