Italian Modernism: A Fascist Trauma Response

Modernism, in its purest form, refers to the artistic movement that attempted to create a new alignment between the human experience and modern technology. To accommodate this new movement, art reformed itself, becoming increasingly more abstract in an effort to encompass and describe societal concerns more fully. Italian artists Alberto Burri and Umberto Boccioni reflect artists that created modernist art that depicted the overall sentiment of Italian society during their respective times. Although their art was made in two vastly different time periods, as Boccioni created Futurist art under Mussolini’s Fascist regime and Burri created art as a response to the traumas left behind by it, they represent changes made to Italian society as a result of a political ideology. It is through the complete study of the primary sources from this time that one can understand the integral nature of these works in the overall understanding of the way in which Italy both coped and lived as a result of Mussolini.

It makes sense to begin the analysis of post-Mussolini Italy at the beginning, with Umberto Boccioni’s most remembered work, Unique Forms of Continuity in Space. Made in 1913 and cast in 1931, Boccioni’s sculpture represents a hopeful and promising Italian future, one that directly contradicts the reality later underlined in Burri’s art. As a Futurist artist, Boccioni celebrated innovation and technology, believing that an increase in industrialization would bring Italian prosperity. Following Filippo Marinetti’s Futurist Manifesto, Boccioni created works that aimed to “glorify war - the only cure for the world.”[1] Almost as a preposition for what would soon come to Italy during the First and Second World Wars, Boccioni created art that promoted violence and chaos, such as his work Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (1913; Fig. 1). Made in 1913, this statue of a charging figure rests at about 43.875 x 34.875 x 15.75 in. in scale, or about the size of a five-year-old child. By creating an in-the-round sculpture that is designed to be looked at from all angles, Boccioni provides viewers the opportunity to see the figure’s warped nature as a result of time and speed. This focus on movement and speed is emphasized in the way in which the metal figure is made to appear as if it is cloth blowing in the wind.[2] The geometric nature of the figure’s head makes its identity unknown, however the sharp angles at its supposed face give the impression of a helmet, which furthermore gives the impression of the figure as a soldier charging into the future. It can be said that this figure represents Italy’s hope; a golden soldier pushing them into the hopeful future. This feeling of charging forward is shown in the way in which the soldier is positioned with its right leg in front of its left. This stance highlights Boccioni’s emphasis on forward movement and momentum, as the soldier is shown rapidly leading the Italian people to the future.

Figure 1. Umberto Boccioni, Unique Forms of Continuity in Space, 1913 (Cast 1950), Bronze, 47 3/4 x 35 x 15 3/4" (111.2 x 88.5 x 40 cm). Photograph. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Lydia Winston Malbin, 1989, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/485540.

Adding to the violence and chaotic nature of the work is the lack of a smooth texture throughout its surface. This furthers Boccioni’s attempt at displaying speed rather than form, as it shows the soldier’s figure fighting against the chaos that is time and motion. This follows closely with the demands of Futurism, as Marinetti believed the “splendor of the world has been enriched by a new beauty: the beauty of speed.”[3] Boccioni evokes this feeling by compelling audiences to follow this Futurist Man into the future, as who would find “use [in] looking behind” when the Italian future is so bright?[4]

Boccioni, when asked about his feelings towards Classical Italian culture, displayed a sense of displeasure. In his 1914 Futurist Painting Sculpture Manifesto, he states that anyone that “considered Italy to be the country of art is a necrophiliac who thinks of a cemetery as a delightful little alcove.”[5] Reinforcing Futurism’s advocacy for forward movement and innovation as Italy’s only chance to leave its classical past and enter a brighter future, Boccioni believed that artistic innovation, in terms of form and medium, was Italy’s beacon into the future. Unique Forms of Continuity in Space makes use of this innovation, as its abstract form and bronze medium exhibits Italian Futurist innovation. The use of bronze is also important as it brings an industrial element to the work, highlighting the need for industrial power to lead Italy into the new age. Furthering these ideas for Italian industrialization was Boccioni’s and many Futurists’ want of war, as many believed that Italy could only fully cut ties with its past through the use of modern technology and military action.[6] Much like Boccioni’s industrial soldier, Futurists welcomed the momentum and violence of the First World War, as they believed it to be Italy’s chance to turn away from their classical roots and become a leading global power.

This romanticization of war and violence, however, is what brought the downfall of the Futurists. As described in Marinetti’s manifesto, art must have a “strict historical relation with the moment in which it appears.”[7] Boccioni and his fellow Futurists believed in art’s inability to be detached from society’s concerns, as they believed their art should reflect and speak to modern Italian society. As mentioned previously, Futurists believed that the only way in which Italy could have the ability to move forward into the future would be through violence and war, meaning they were some of the strongest supporters of the First World War. However, just as fast as the war began, it ended, and with the end of the First World War came a decline in Futurist support as many members turned to different artistic styles as a result of the social, economic, and political depression forced upon Italy. In a period known as the return to order, Italian society began to disagree with the violent nature and rhetoric of Futurism, as artists became disillusioned by the technology that contributed to the devastation left behind by the war. Italy’s socio-economic issues caused by the large expenses of the fight furthered these feelings of resentment, as increasing debt forced the country into an economic depression, one that many blamed solely on the war. Increasing feelings of nationalism, found in posters fighting for a self-sufficient Italy, began to be seen across the country.[8] These posters, which argued that it was the fault of the country’s “lazy” citizens that the economy was failing, followed closely with the ideals of the fascist party. These posters promoted self-sufficiency, they provided the humiliated Italian public with a way to reclaim their power and prestige. They provided them with a way in which they could rise again from the shame of the First World War. This, in conjunction with growing resentment towards the government created a feeling of desperation for salvation, one that many believed could be found under Mussolini. It is here, in this setting of desperation, that the second, more extreme, generation of Futurism began.

Led by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, the second generation of Futurism followed and promoted more fascist and extremist ideologies than its first generation. As a response to the effects of World War I on Italy, this second generation promoted a strongly patriotic, violent, and anti-parliamentary democracy rhetoric. These ideals closely followed those of Mussolini, who officially accepted Futurism as an art movement in 1922. In his encyclopedia entry, What is Fascism, Mussolini highlights the violent and expansionist nature his new Italian State should take on. He describes the Italian people as one who are “rising again after many centuries of abasement and foreign servitude.”[9] Following the Futurists' anger at the result of the First World War, Mussolini describes an Italy that renounces the idea of “perpetual peace” as the way to center itself as a global power. In other words, Mussolini chose to embrace violence in order to put Italy in its rightful place as a central global power. As a supporter of violence to heighten Italian importance, Futurism provided an art form that was able to spread fascist ideologies through a medium that was easily accessible. With time, Futurist artists became trapped in the creation of art for a fascist state, as their art has now forever become tied with the promotion of these ideologies.

It is this sense of incredibly strong and dangerous nationalist sentiment that brought along the downfall of fascism, and by extension, Futurism. After the end of the Second World War, which ultimately led to Mussolini’s downfall, Italy, much like the rest of Europe, experienced a period of economic, social, and political depression. Alberto Burri, an Italian artist from Città de Catello, used this period to create art that depicted the drastic decline in Italian morality as a result of the war.

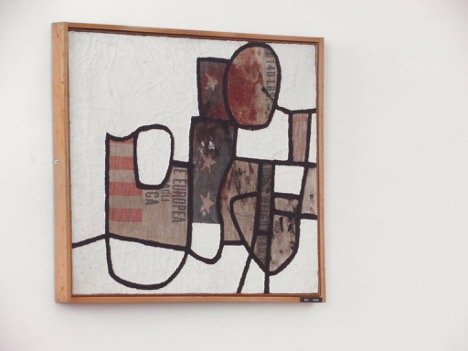

In a series of artworks labeled Sacchi, Burri was able to convey both Italy’s spirit and trauma at this time. Made from the burlap sacks holding food provisions brought from America under the Marshall Plan, Burri created artworks that allowed the Italian population to grieve and work through traumas from the Second World War and Mussolini’s rule. SZ1, created in 1949 using a collage of oil paints and burlap sacks on a white canvas, is an example of one of these artworks (Fig. 2). What was once a country that created works promoting Italian pride and innovation was now a country in which artworks depicted their war-torn, injured nature. As the first of Burri’s Sacchi series, SZ1 created a template for his works to openly display an Italian dependence on American aid as it “prominently paraded a star-spangled United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration sack” as its main subject.[10] This dependence is also seen in the way in which the sack is cut up, rearranged, and painted over to create the illusion of an American flag. The black outline surrounding each section provides audiences with clear distinctions between each one, however the overlapping red paint brings a sense of cohesion to the work as a whole. The colors are dull, alluding to a somber atmosphere surrounding the artwork’s creation. The two brightest colors are found in the blue section at the works center in which three state stars are shown, as well as in the red stripes to the left side and the red paint at the top. Reminiscent of crusted, old blood, the red paint at the top is placed on the work at varying levels of density, as if the sack was used to cover a bleeding wound and the blood spread throughout the work. The thick, black outline surrounding the sections also creates a definite contrast between the white background of the canvas and the “bloodstained” sack, creating a feeling of separateness between the sterile nature of the canvas and the dying nature of the sacks, a contrast that is reminiscent of a patient bleeding out on a hospital bed.

Figure 2. Alberto Burri, SZ1, 1949, oil on burlap, 18 7/8 x 22 13/16” (48 x 58 cm). Photograph. Dage. August 2018. Fondazione Palazzo Albizzini Collection Burri, https://www.flickr.com/photos/64552256@N08/44423869831

Most interesting in Burri’s SZ1 was the clear acknowledgement created in declaring the sack’s location of origin. Clearly written in the leftmost section is an indication of the provider, “dagli America” and the receiver “Europea.” With this distinction, the work highlights the “mythic excess of postwar America,” a highlight that creates a political sting to any Italian viewer of the work. Burri’s SZ1 removes any glamor or pride Italy may have possessed, as it reduces the nation “to the status of a colony, relegated to the Third World.”[11] What once was a country of excess, of golden sculptures like those made by Boccioni, has now been diminished to a country dependent on others for food and money. Rather than create art that celebrates and looks to the future with a sense of pride and optimism, Burri creates art that reflects a dismal state, one in which there are very few reasons to be optimistic for a bright and strong Italian future.

Boccioni’s Unique Forms of Continuity in Space and Burri’s SZ1, when compared, portray the most ideal way to understand the changes Italy experienced as a result of the war. Whereas before, Italian artists focused on a stronger future in which the use of technology and Italian power could propel the nation forward, post-World War II Italian art focused on an emotional and spiritual realization of the impacts of fascism and violence. The main parallels that can be drawn between the two artworks is understood when considering the mediums with which the artworks were created from. Boccioni’s sculpture, made with bronze and coated with a gold finish, is symbolic of the luxe and grandeur Italian culture believed itself to be prior to World War II. His work represents a sense of patriotism and understanding of Italian greatness, one that is only strengthened by the wealth and abundance the work’s gold finish implies. This sense of luxe and wealth is nowhere to be found in SZ1, as the work is created using a material given to Italy due to their need for basic goods to survive. The use of burlap, a much less industrial and modern material than bronze, reminds viewers of Italy’s failure in industrialization and its inability to reach the goals conveyed within Boccioni’s works. Burri’s works, in this context, convey Italy’s failure.

One of the most important messages SZ1 brings to audiences is the acceptance of American dependency. Clearly signified on the artwork is “dagli America,” which roughly translates to “from America.” Written plainly and placed at the center of the work, Burri highlights Italy’s dependence on America for food and money. America, with the implementation of the Marshall Plan, has become at this time a key factor of Italy’s future, as it has begun to provide Italy with the physical materials to recover, such as food and money, as well as the metaphorical materials to recover, such as the burlap sacks which Burri uses to work through Italy’s traumas. This highlight shows the true defeat of fascist ideologies as Italy began to lose any notions or hopes for continued “self-sufficiency,” a sentiment that only grew as Italy was gradually brought fully under the wing of the “cultural and economic neo-imperialism of the U.S. Marshall Plan.”[12] Gone was the Italy Mussolini boasted about, the one in which its people were “rising again,” as Italy became the third largest recipient of aid from the Marshall Plan, being sent a total of about $12 billion to be redistributed and used in rebuilding efforts.[13] Rather than remaining self-sufficient, Italy now was dependent on America for relief and recovery, dependent on them to “[rise] again.”[14] The Marshall Plan’s murder of Mussolini’s self-sufficient Italy is highlighted explicitly in Burri’s SZ1.

Through their works, both Boccioni and Burri attempted to create art that spoke to an entire country, and it is only by studying the two alongside each other that the true effects of the Second World War and Mussolini can be understood. Together, they created art that must be understood through a period eye, as they created art that promoted “‘spectator participation’ in the constitution of the [works’] meaning.”[15] By creating art that interacted with the surrounding social, political, and economic atmosphere, Boccioni and Burri allowed viewers to engage with their works on a more personal level. It was through art that Italy was able to understand its present, whether that be an idealized version or coping with its downfall. By studying these two artworks, one can see an emotional history of Italy before, during, and after the Second World War. Boccioni and Burri, when studied together, depict the story of the fall of Italy’s “what could have been.” They display Italy’s attempt to use modernist art to understand their society and the role they play in the global stage

Endnotes

[1] Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, “Il Manifesto Del Futurismo”, 1909.

[2] Umberto Boccioni, Unique Forms Of Continuity In Space, 1913 (Cast 1931 Or 1934) | Moma, 2022, The Museum Of Modern Art, https://www.moma.org/collection/works/81179.

[3] Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, “Il Manifesto Del Futurismo”, 1909.

[4] Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, “Il Manifesto Del Futurismo”, 1909.

[5] Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, “Il Manifesto Del Futurismo”, 1909.

[6] Umberto Boccioni, Futurist Painting Sculpture, trans. and ed. Maria Elena Versari and Shane Agin (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2016).

[7] Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, “Il Manifesto Del Futurismo”, 1909.

[8] “Laziness - Poverty, Work - Wealth, Italy”, 1920, [Place of Publication Not Identified: Publisher Not Identified] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2021670939/.

[9] Benito Mussolini, “What is Fascism,” 1932.

[10] Jaimey Hamilton, “Making Art Matter: Alberto Burri's Sacchi” ,October Magazine 124, (Spring 2008), Cambridge: The MIT Press, https://direct.mit.edu/octo/article-abstract/doi/10.1162/octo.2008.124.1.31/56077/Making-Art-Matter-Alberto-Burri-s-Sacchi?redirectedFrom=fulltext.

[11] Hamilton, “Making Art Matter: Alberto Burri's Sacchi”.

[12] Hamilton, “Making Art Matter: Alberto Burri's Sacchi”.

[13] Michela Giorcelli and Nicola Bianchi, “Reconstruction Aid, Public Infrastructure, and Economic Development: The Case of the Marshall Plan in Italy” (National Bureau of Economic Research, December 2021), https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w29537/w29537.pdf.

[14] Benito Mussolini, “What is Fascism,” 1932.

[15] David Craven, “The Latin American Origins of ‘Alternative Modernism”, Rashid Araeen, Sean Cubitt, and Ziauddin Sardar eds., The Third Text Reader on Art, Culture, and Theory, London, New York: Continuum, 2002, 24-35.

Author Bio

Carlotta Piantanida

is a junior at Swarthmore College working towards a bachelors in Art History and Classical Studies. Her studies primarily focus on European, more specifically modern Italian art, however she is also interested in the connections between Ancient Roman art and how it was used under the Mussolini regime. Through her studies, she seeks to increase the accessibility to art and history, ensuring that everyone, regardless of background, has the ability to access art and history from all around the globe.