Transphobia in the Media: Crossdressing as a Point of Fear and Comedy

By Julia Federing

“Literature is a picture, or rather in a certain sense both a

picture and a mirror; it is an expression of emotion,

a subtle form of criticism, a didactic lesson and a document…”

–Fyodor Dostoevsky [1]

Film as a visual medium has been established as one of the most accessible displays of the human condition, nuanced philosophical discussion, and societal examination since its invention at the turn of the twentieth century. Despite its adolescence as a vehicle for narrative, film was, for a time, the most popular storytelling form, surpassing theatrical performances, stage plays, and technical innovations such as FM radio. However, due to the invention of television and its emergence as a separate genre, film has now emerged as one of many alternatives to experiencing moving, visual art. Artists began to utilize this art form to examine the human psyche and the environment from which it was constructed to more complex examinations such as the desire for self-discovery. Gender and sexuality when expressed in this fashion is often used as a foil for this desire and can be utilized to grapple with one’s identity being either outside the norm or accepted at any capacity, the most contentious being identities under the trans hypernym (transsexuality, crossdressing, etc.)

In this essay, my aim is to:

(a) Define the various terms: “transgender,” “transsexual,” “sex,” “gender,” “crossdressing.”

(b) Examine the history behind crossdressing in generalized storytelling, from theater to film.

(c) Assess the two largest patterns of such representation: crossdressing as a point of fear and as a point of comedy.

(d) Underline the negative impacts of said representation.

(e) Discuss the constraints and limitations of my own work.

Collage of crossdressing representation throughout media, by Julia Federing

WHAT IS GENDER, ANYWAY?

Let’s start with the basics. Literature and culture scholar John Phillips plainly defines sex as a construct rooted in “anatomical differences, specifically in the nature of the reproductive organs” in his publication Transgender On Screen, an “inescapably physical (somatic) dimension that extends throughout the both mind and body.”[2] Phillips’ novel is very thorough, as is his other research on French literature, as he makes a point to highlight intersexuality or “hermaphrodites,” as Phillips refers to them in his definition.2 Intersexuality, where an individual has both sets of genital organs, is extremely rare in varying aspects, and like other minorities, it is often forcibly assimilated to the dominant culture. An infant with an ‘intersex’ set of genitalia, for example, will be routinely neutered to conform to either end of the binary, an established practice and often without parental consent. And yet, scientific research conducted in the late 1990s discovered that “‘biological’ sex encompasses chromosomal and hormonal makeup in addition to internal/external genitalia,” an increasingly woven set of parameters that is often both dismissed and ignored by other scholars.[3] For a more all-encompassing definition, sexuality will be evidently defined as the combination of “anatomical differences” as Phillips suggested, with the additional caveat of chromosomal and hormonal composition in the human body.

Gender, however, is all the more convoluted, altering and morphing in definition every few years since the trans hypernym has become increasingly tolerated in the public consciousness. How, then, does one define gender? Prominent gender theorist Judith Butler proposes the theory as a “repeated stylization of the body,” strictly regulated and structured by any present culture’s frame of reference.[4] Yet in a separate dissertation, Butler contradicts her former conclusions and allocates gender as a repetitive performance with no concrete origin, a self-fulfilling cycle “constituted by the very ‘expressions’ that are said to be its results.”[5] Scholar and associate professor Jennifer Drouin says similarly in the discussion of drag, using Butler’s findings to claim that the art of all ‘gender parody’ is acceptable since gender is a concept with no definition.[6] But if gender is a framework with no first emergence, then how was its definition given? Its origin must start somewhere. The most immediate explanation lies in the gaze of sexuality and the pressures of dominant influences, perceptions, and culture. What was considered masculine in the Georgian era of Great Britain and Western Europe is considered feminine by today’s standards, and in some cases vice versa. Cultural standards change, and thus gender presentation to fit these standards change as well. Therefore, for the use of this essay, we’ll proceed with Butler’s many definitions with some slight modifications: “a repeated stylization of the body governed within the framework of a culture’s most predominant influences.”

Evidently, the terms sex and gender are extremely fragile and require frequent amendments to stay relevant and accurate to present-day notions, making the trepidation over said framework even more destructive. But in order to proceed, “transgender” and “transsexual” must also be defined as well as understood. As noted in Nicholas Clarkson’s “Terrorizing Transness,” most terms under the trans hypernym (“transsexual,” “transvestism,” “cross-dresser,” etc.) are used interchangeably, especially by collectives external to the trans community, creating discontinuity at best, and misinformation at worst.[7] Professor Emerita of Gender and Women’s Studies Susan Stryker defines “transgender” as individuals who “cross over (trans-) the boundaries constructed by their culture to define and contain that gender ”.[8] Clarkson draws similar conclusions but delineates a particular difference between “transgender” and “transsexual:” the former is concerned with individual identity, while the latter has certain “medicalized connotations” i.e., has been under some form of surgery.[9] Scholar Stephen Whittle outlines transsexuality in a similar manner and is the most operational in definition, including a presumed sense of “incongruity” or dysphoria with one’s anatomical sex, thus seeking medical aid to rectify that imbalance.[10] Such a definition, however, excludes individuals who either (a) don’t have access to medical aid, (b) can’t afford it, or (c) have no desire to do so. Therefore, the term “transsexuality” will be categorized as a more niche alternative. Transgender, as Clarkson describes it, is more readily concerned with the concept of gender itself, and is therefore more culturally and psychologically oriented. Phillips adds, in a loftier fashion, that the term “transgender” is more comprehensive, used to “denote all of the above [cross-dressers, drag-queens, transsexuals] and to include anyone oppressed because of their gender identity or gender presentation,” including genderfluid and nonbinary individuals.[11] If “transsexuality” is a person seeking cover, then “transgender” is the umbrella.

And finally, what is crossdressing? Coined by Magnus Hirschfeld in their book Die Transvestiten (1910), crossdressing is a rather broad term to describe individuals whose gender presentation is incongruent to their anatomical sex.[12] Older and more archaic definitions, however, denote the practice as one with the goal of deriving erotic pleasure, including the fetishization of the gender they wish to exhibit.[13] Therefore, due to Phillips’ surprising inclusion of such a doctrine, Drouin’s perspective will be the primary basis of our definition.[14] Psychologists would even categorize these presumed notions along the binary, classifying “heterosexual” and “homosexual behaviour patterns” as an attempt to re-assimilate these “deviants” to the dominant standard. Regardless, the practice was originally noted as a behavior conducted by “transvestites,” a pejorative that will not be used in this context[15]; “transgenderism” and “fetishistic transvestism” will also not be utilized for the same reason. Gender theorists and essayists today still associate crossdressing with the intent to disguise and adopt both perceptions and behaviors of a gender identity that is not their own i.e., the “opposite sex,” a subject that will be analyzed in the following section.[16]

A HISTORY OF EURIPIDES, ARISTOPHANES, AND MEN IN WIGS

The earliest-known examples of crossdressing as a narrative theme or motif dates back to Ancient Greece, an environment that also established the idea of ‘boy actors’ or young men acting in female roles; in some cases these men would perform multiple parts, wearing different masks to signify each part.[17] Most playwrights of this period also utilized their craft for social commentary, particularly in their comedies, while tragedies provided an “outlet for the social conscience.”[18] Scholar Abbey Elder examines a variety of Ancient Greece’s most popular comedies and tragedies containing themes of literal crossdressing and subversive gender deviance, but for the sake of this analysis I shall only refer to the more direct examples as evidence. Elder identifies a plethora of commonalities amongst these works, particularly in regard to a protagonist’s illusive motivations when crossdressing. Two plays by Aristophanes utilize body hair as a symbol for gender expression: in Ecclesiazusae, when a sect of Athenian women begin to disguise themselves as men to overthrow their government[19]; wherein Thesmophoriazusae, a Kinsman of the sovereign Euripides undergoes various aesthetic transfigurations to invade a women-only religious festival.[20] Elder also notices that both plays contain themes of infiltration, and in particular to Thesmophoriazusae, to access women-only intimate or ‘vulnerable’ spaces. However, in Ecclesiazusae, the women’s desire to cross-dress stems from a place of arrogance and a desire to seize, in firm belief that they can govern better than their male counterparts.[21] In combination, both plays set a precedent for trans women to be viewed as perverted infiltrators and trans men as ravenous for power and authority, an overused binary present in modern media’s representation of transsexuality. A commonality also noticed by Elder is the narrative’s resolve to heteronormativity which will be touched upon in a later section; the crossdressers are punished and the status quo endures, and all's right with the world.[22] Surprisingly, crossdressing was treated with more ambivalence than expected, but the practice was nonetheless either played for laughs or utilized briefly as a lens for social commentary.[23]

Terracotta statuettes of actors, Late Classical Greek, late 5th–early 4th century BCE, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1913. https://urldefense.com/v3/__https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/248763__;!!KIFmrYtlezdzESbnm_I!D5oz0MdPKjV1Y7SFDGVihzw1850ptH1CyDbjW83PT7-BsFI50FxqvWrXM9i7Kw9Q18ZO6ThgALjrWjlIdW_CuZukS_AM5qOFFnyung$

Both Ancient Greece and Rome are considered the dual foundations of Western civilization, therefore most narrative motifs from this period, including crossdressing, would logically endure in modern Western cultures. It wasn’t until the domination of Christianity in the Middle Ages that led to the practice being considered taboo and not even entertained by the populace[24]; and since women still were prohibited from the performing arts, the acting profession also plunged in respectability. The medieval church dubbed crossdressing both an act of heresy and an element of witchcraft, a morale that even led to Joan of Arc’s execution in 1431.[25] Fast forward to the nineteenth century when homosexuality was criminalized in Great Britain which, at the time, included any behavior under the trans hypernym. Gothic novels told tall tales of Satan’s emissaries adopting a disguise of the opposite sex as a means of seduction, while other novels portrayed the reveal as mere hijinks.[26] Nonetheless, the precedent was established: crossdressing became the stand-in for any gender transgression, and the act was connoted as unforgivably fallacious with ulterior motives in mind.

THE INVASION OF THE MURDERING-CROSSDRESSER

Crossdressing wouldn’t become established as a tangible threat, at least in the American consciousness until the mid-1950s. Serial killer Ed Gein, also known as the “Butcher of Plainfield,” was the son of a dysfunctional household: an alcoholic father who was all but present in young Gein’s life while his domineering, hyper-religious mother would fill his head with various Puritan ideals, including that all women—besides herself—were promiscuous and instruments of the devil.[27] After her death, Gein went on a ravenous spree, murdering and exhuming the corpses of women who resembled Gein’s mother, after which he fashioned their skin into various upholstery and other furniture.[28] When Gein was arrested and put on trial, the American public was in a frenzy: “the country was fascinated by… the type of menace [Gein] represented” according to essayist Lindsay Ellis, “a sexual deviant, an Oedipal nightmare, depicted in the press as a feminine and gender-confused man.”[29] Press and local news were obsessed not only with the horrific nature of his crimes, but took particular interest in the Gein’s’ abnormal mother-son dynamic, twisting and morphing Gein’s own Oedipus complex into something unrecognizable:

After an unidentified investigator supplied the Milwaukee Journal with information on Gein, the November 21st issue of the journal ran a story claiming that Gein… “wish[ed] ‘he had been a woman instead of a man’ and wonder[ed] ‘whether it would be possible to change his sex.”[30]

Now, all of these fabrications were merely that, fabrications. Any and every supposed ‘slip to the press’ were spread before any real psychoanalysis of Gein had been conducted, and the psychiatrists who analyzed Gein concluded that he displayed zero indications towards homosexuality or transvestism.[31] But the damage had been done—in 1959, American fiction writer Robert Bloch wrote the hit novel Psycho inspired by Gein’s murders, a narrative which film director Alfred Hitchcock adapted into the critically acclaimed motion picture the following year.

There are two easily discernible adaptations of Ed Gein and his various crimes, Hitchcock’s Psycho and Silence of The Lambs. Psycho’s translation of Gein more focused on the Oedipal aspect of his psyche, including scenes where the fictional Norman Bates is so consumed by his long-dead mother that her presence became an additional, dissociative identity within Bates’ subconscious. Bates is heard conducting conversations between himself and his “mother” persona, and parades around his motel as his mother when Bates takes the life of his victims.[32] Furthermore, the motivations behind Bates’ or “mother’s” killings are out of self-preservation, a twisted form of castration anxiety that always takes hold whenever Bates is even remotely attracted to someone.[33] Silence of The Lambs, on the other hand, is more directly inspired by the specific nature of Gein’s crimes, whereas the fictional killer Jame Gumb a.k.a. “Buffalo Bill” murders and skins numerous women to fashion himself a “skin suit,” “a literal invasion of other bodies.”[34] Differing from the source material, Bill finds erotic pleasure in his disguise, playing into the more archaic notions of crossdressing or “transvestism” as seen on page four.[35] Both films deal with themes of body possession, and psychosis, but most alarmingly, men parading as women to infiltrate and assault their most vulnerable spaces, with the most extreme case in Lambs being the body itself. Furthermore, both films sought to detach their narratives from ‘transvestite’ biases and assumptions by citing their respective serial killers as victims of their Oedipal psychosis, however the actions of the narrative trump said progressive attempt. Both antagonists cross-dress, plain and simple, thus their narratives still fall under the trans hypernym regardless of any caveats they seek to introduce and cannot be excused from analysis.

“Psycho” Film Poster (1960)

The cultural effects behind these two films in American culture and entertainment are astounding. Psycho’s eventual critical acclaim led to an explosion of dramas containing the “murderous-crossdresser trope” in the 1970s and 1980s, including Deadly Blessing, No Way to Treat a Lady, Dr. Jekyll and Sister Hyde, Deranged, Stripped to Kill, Three on a Meathook, Dressed to Kill, and many others.[36] Silence of the Lambs codes Buffalo Bill as “hideously-queer,” “a gay man who lisps and cavorts around his dungeon basement, listening to ‘Goodbye Horses’ and carrying around a poodle named Precious,”[37] reinforcing the stigma that queer individuals, especially trans individuals, have both murderous intent and some form of psychosis. The environment concocted in these films was one of extreme anxiety, self-preservation, and above all, hatred towards the trans community, skeptical of any man who claims he is a woman. Because if one of them is lying, who knows, maybe they’ll put on a wig and stab you in the shower.

GENDER HIJINX: AN EXERCISE IN SUPERFICIAL PROGRESSIVISM

There are two primary facets of the crossdressing motif in relation to the audience: when the audience is unaware of the deception, and when they are not; the former plunges the audience into the perspective of the fiction, one of fear and betrayal when the deception is revealed, while the latter establishes an atmosphere of dramatic irony as a form of gender-subversive hilarity unfolds for the gaping viewer.[38] While similar themes are present in their more horrific counterparts (i.e., Psycho, Silence of the Lambs), comedic portrayals of crossdressing reinforce the status quo in a more lighthearted fashion, and any subversion or progressivism displayed is dismissed just as quickly within the film’s “narrative trajectory.”[39]

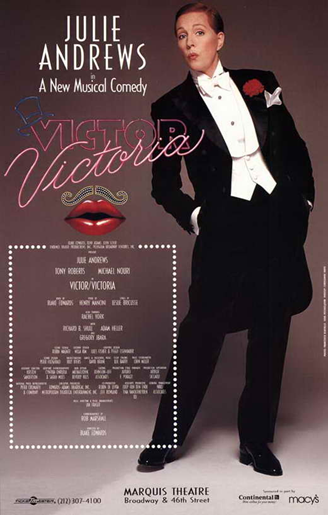

Victor/Victoria tells the story of a female soprano who cosplays as a gay Polish “female impersonator” or drag-queen to find work, skyrocketing the singer to stardom as the film progresses. In essence, Victoria uses her stage presence “Victor” to obtain a sense of “patriarchal privilege” she was denied access to as a white woman by masking herself as a minority in the music industry—“a woman pretending to be a man pretending to be a woman”[40]—a rare commodity in the film’s setting.[41] Throughout the narrative, Chicago gangster King Marchand becomes enamored with “Victor” at one of his performances and is so distressed by the initial pseudo-reveal, Marchand commits a federal crime by breaking into “Victor’s” hotel bathroom to discover that ‘he’ is actually a woman.[42] This unnerving twist to the infiltration motif popularized by Psycho has been twisted and subverted into a more ludicrous, ironic perspective, but is still the device, nonetheless. Victor/Victoria also plays with the notion that the hidden is in fact the truth which, when applied to trans individuals, implies that their sexuality at birth is their destined gender identity.[43]

“Victor/Victoria” Film poster (1982)

Some Like It Hot, similar to Victor/Victoria, gives an alternative presentation of various thematic and narrative devices associated with the crossdressing motif but remains non-subversive in execution. Instead of a woman disguising herself as a man as a means for profit, two struggling jazz musicians, Joe and Jerry, go incognito as members of an all-girls band after witnessing a mob execution, thus mortally in danger. Similarly to Victoria and King’s relationship, Joe falls in love with the band’s lead singer Sugar Cane while in disguise as a woman, going so far as to display a completely separate ‘millionaire shy-guy’ persona to woo her. Sugar Cane was played by the iconic Marilyn Monroe, a pre-established sex symbol by the film’s release, therefore Monroe’s performance implies to the viewer that Cane symbolizes every man’s ideal woman. Contrary to Victoria’s encounters in her new environment, Jerry almost becomes enticed by his new-found access, acting as a charlatan to obtain as much ‘forbidden knowledge’ as possible, the kind only revealed in the opposite sex’s most vulnerable spaces. Both he and Jerry compete for Sugar’s affection while maintaining their disguises, reinforcing the stigma that individuals of the LGBTQ community, from trans women to lesbians, are secretly attracted to the women with whom they share a close proximity.[44] Furthermore, when Joe and Jerry comment on Sugar’s beauty, they do so in an objectifying manner: “Boy, would I love to borrow a cup of that sugar!”[45] Finally, the ‘unveiling’ moment in the film—when Joe and Jerry confess to their deception by removing their disguises—is once more light-heartedly accepted at the film’s end, fortifying heteronormativity’s superiority and the exclusion of any other alternatives.[46]

Some Like It Hot, directed by Billy Wilder (1959; Hollywood, CA: MGM/United Artists, 2011).

Thirdly, and possibly most contentiously, The Rocky Horror Picture Show tells the story of eccentric scientist Dr. Frank N. Furter, an alien transvestite from the fictional planet Transsexual, and his interactions with a hastily engaged couple and their respective spheres. The film, to put it plainly, is about as nonsensical and irrational as you could possibly get with most pictures of its magnitude, quickly dubbed a cult classic after its initial release; if anything, Rocky Horror midnight showings are almost as celebrated as the film itself. The unfortunate truth of the matter is that Rocky Horror, like the other two films previously mentioned, is superficially progressive to the same degree. The hastily engaged couple, Brad and Janet, are stand-ins for the present culture’s rigid heteronormative attitudes whilst Dr. Frank N. Furter and his companions are the zany, erotic equivalents of the queer community.[47] The film’s resolution sees the doctor executed for his crimes while Brad and Janet are left to rehabilitate themselves after their experience, reinforcing heteronormativity’s supremacy in American culture with an oddly positive connotation, as if the literal alienation of the LGBTQ community is “all as it should be”. The narrative progression of the film is just as concerning, as Brad and Janet are coerced into adopting the ‘transvestite’ attitudes of Furter and his companions. As an undergraduate at the University of Oklahoma puts it, Brad and Janet “conform to nonconformity.”[48] This statement has numerous implications, namely that their ‘transition’ to a queer lifestyle was forced and solely due to exposure, sustaining conservative fears that their children will become queer if, and only if, they become exposed to non-heteronormative behavior.

The Rocky Horror Picture Show. directed by Jam Sharman, (1975; Los Angeles, CA: Twentieth Century Fox).

Films like Victor/Victoria and Some Like It Hot are in essence non-subversive, despite their non-conventional interpretations of certain tropes, because of the narrative return to normalcy: “they play off of homophobic anxiety and… ultimately serve heteronormativity… after accomplishing the task of denigrating homosexuality and allaying fears about it.”[49] The themes present in both examples, from the access to forbidden knowledge to crossdressing as a means of deception, are submissive to the narrative’s abiding goal of maintaining a heteronormative status quo, so much so that films like The Rocky Horror Picture Show become the queer community’s sole pillar of ‘good’ representation, no matter how problematic and self-destructive its content may be. These failings in queer representation oppose any promises these queer narratives make to contain a progressive narrative and spark vast ripple effects in the public’s generalized understanding of transgender people for the very same conclusions presented. Moreover, such narratives feed on the fears concocted by these representations, specifically the invasion of privacy and the “conform to nonconformity” throughline illustrated by Rocky Horror, thus establishing an environment permeated by toxicity and bigotry.

IMPACT

In 2017, the Gay & Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation, largely known as GLAAD, conducted a demographics and statistics report on the number of known transgender homicide victims, publishing the study in March of the following year. According to their findings, ninety-six percent of the homicide victims that year were either transgender women or feminine-presenting, and ninety-two percent were people of color.[50] Forty-six percent of the homicides remained unsolved, and at least twenty-two of the twenty-six victims were misgendered in initial reports of their deaths. The inescapable truth of these deaths was they were preventable, and above all, conducted with at minimum an unconscious sense of bigotry and hatred. “Race is central to the division of ‘good,’ [and] patriotic” according to Gender Studies professor Nicholas Clarkson, and is used to “potentially assimilate [the] trans subjects”.[51] When entertainment influences the public consciousness so heavily, what may be perceived as fiction trickles into the psyche as unconscious prejudice; as a result, those who suffer the most are individuals who fall under more than one marginalized category.

Its influence even reaches popular culture and Internet humor, constantly reinforced by the toxicity accompanied with heteronormativity. In 2019, a popular element of cultural humor, (also known as “memes,”) specifically in more conservative and toxic sects of the Internet, was the quip that to have sex with a “trap”—an individual who is not biologically female but is minimally feminine-presenting—as a man was homoerotic in the derogatory sense.[52] To call a trans woman, feminine-presenting man, or any individual who fits this category “deceptive,” was referred to as a “trap” egregiously, so much so that the term is now identified as a slur.[53] This kind of harassment stems not only from a fundamental misunderstanding and denial in regard to transsexuality but a petrifying fear to be seen as anything but the assimilated standard. These individuals not only don’t understand what it means to be transsexual, but they don’t believe it exists at all, and to have intercourse with a trans woman is to actually have sex with a man.

Minority collectives oftentimes marginalize members of their own community for the same reason. For example, during the second-wave feminist movement in the 1970s, many lesbian feminist communities began to isolate trans women in their own spaces, using buzzwords like “infiltration” and “deception” in these debates.[54] Lesbian activists like the infamous Janice Raymond would accuse trans women of being “secret agents, sneaking into this [feminist] space… [then] consorting with the enemy” for patriarchal domination, fostering division and reinforcing other bigotries, from ableism to racism.[55] This sect in radical feminism became separately defined as trans-exclusionary radical feminism, and those who perpetrated such ideals were labeled TERFs within the feminist community. Any semblance of gender variance became associated in the American consciousness with “deception, criminality, and concealment,” and this attitude has persisted even into the realm of global politics and terrorism campaigns.[56]

In short, to dismiss transphobia in American culture as a niche dispute in the interaction of entertainment and sociology is to ignore the smoke and debris of a burning building: it’s conditioned if not deliberate, and above all, passive. Inaccurate representations of transsexuality follow the same pattern, as trans men are perceived as women “taking on masculine attributes… [and] viewed as usurpers” while the notion of men taking on femininity is seen as “corrupted” or blasphemously weak.[57] Transsexuality has even begun to be fetishized in pornographic circles, but still under intense stigma. According to AlterNet in 2016, the “shemale” category was one of PornHub’s most popular divisions; after conducting an experiment, adultempire.com moved their “shemale” content from their trans site to straight site, thus causing views to increase by fifty percent.[58] Even misrepresentations of transsexuality fall under the gender binary, and the trans community is either objectified or reviled in online spaces. What once emerged as a thought experiment of the ancients has festered and contorted into a cultural disease, a crisis both in the ethics and morals of the American media and its exploits; because now the question is, how do you stop?

WHAT’S LEFT IN THE CONVERSATION?

On June 6th, 2020, British author and philanthropist Joanne “J.K.” Rowling retweeted an op-ed deliberation over “people who menstruate,” evidently taking issue with the article’s inclusivity by refusing to refer to these individuals as women. What began as a mindless series of characters—as most tweets are—descended into a cacophony of vitriol as Rowling regurgitated some of the Internet’s most telling signs of transphobic language. “Erasing the concept of sex;” “I’d march with you if you were discriminated against;” “If sex isn’t real…;” the list goes on and on.[59] The backlash against Rowling’s comments was, mildly speaking, volatile. Four days later, Rowling revealed in a 3600--word essay that she is both a sexual assault and domestic abuse survivor from her first marriage and thus finds the idea of “men gaining access to women’s spaces” disturbing and, in her words, highly “trigger[ing].”[60] Here, Rowling outwardly associates any progress in trans rights, specifically the rights of trans women, to her repeated assault from more than twenty years ago; and while her trauma is both tangible and indisputable, that experience bears little to no resemblance to the ratification of trans individuals gaining easier access to legal recognition. Her unconscious association exists due to decades of supplanted transphobic ideals, from Euripides to Psycho to Janice Raymond; but Rowling is unaware of that. So, naturally, she redistributes such chauvinism in the name of self-preservation, cascading throughout every corner of the Internet and other facets of human culture. The stereotypes are perpetuated, and the violence continues.

J.K. Rowling from Twitter (2020)

https://twitter.com/jk_rowling/status/1269382518362509313?s=20

Artists like Rowling reinforce this parasitic cycle in the public consciousness and proves once more that while life may imitate art, the relationship works both ways. Furthermore, Rowling’s influence as a public figure reveals her behavior to be extremely concerning as her effect is all the more palpable. And yet, her actions are one domino in a surging effect of unconscious and conscious prejudice. The crossdressing motif and its symbolization of the trans hypernym has been a fascination of Western culture since its very foundation and has persisted to the present day, from cult film classics to the darkest subsections of the Internet (pornography, Internet memes, etc.) wherein such depictions of said identities are fetishized if not objectified. Trans individuals are described as illusive beings, usurpers designed to torment the individuals around them because of their refusal to abide by the gender binary; in other words, Western culture has once again vilified even the smallest threat to the status quo. As a result, the trans community is vilified on a daily basis, from passive discrimination to premeditated murder. Its design is systemic, one that plagues both American society and beyond; and it cannot begin to be dismantled until its populace as a whole recognizes this dilemma that has enveloped the Western space, for entertainment is both a window and mirror to life; it gazes, and it reflects.

Endnotes:

[1] Fyodor Dostoevsky. Poor Folk (St. Petersburg, Russia:St. Petersburg Collection. 1846.)

[2] John Phillips, Transgender on Screen (Hampshire/New York: Palgrave Macmillan. 2006), 8, 21.

[3] Phillips, 8; Claudia Dreifus, “A CONVERSATION WITH -- Anne Fausto-Sterling; Exploring What Makes Us Male or Female.” 2001. The New York Times. January 2, 2001. https://www.nytimes.com/2001/01/02/science/a-conversation-with-anne-fausto-sterling-exploring-what-makes-us-male-or-female.html.; Jackson Taylor McLaren et al, “‘See Me! Recognize Me!’ An Analysis of Transgender Media Representation.” Communication Quarterly, vol. 69, no. 2, (Jan. 2021): 174.

[4] McLaren et al, “‘See Me! Recognize Me!’ An Analysis of Transgender Media Representation,” 174-175.

[5] Phillips, Transgender on Screen, 12; Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (New York, NY and London, UK: Rouledge, 1990), 10.

[6] Jennifer Drouin, “Cross-Dressing, Drag, and Passing: Slippages in Shakespearean Comedy,” Shakespeare Re-Dressed: Cross-Gender Casting in Contemporary Performance, Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, (2008): 23.

[7] Nicholas L Clarkson, “Terrorizing Transness: Necropolitical Nationalism.” Feminist Formations, vol. 32, no. 2, (2020): 165.

[8] Susan Stryker, Transgender History: The Roots of Today’s Revolution (Berkeley, CA: Seal Press 2008), 1.

[9] Clarkson, “Terrorizing Transness: Necropolitical Nationalism,” 165.

[10] Phillips, Transgender on Screen, 9.

[11] Phillips, 11.

[12] Drouin, “Cross-Dressing, Drag, and Passing: Slippages in Shakespearean Comedy,” 24; Phillips, Transgender on Screen, 8.

[13] Phillips, Transgender on Screen, 8-9.

[14] Phillips, 9.

[15] Phillips, 9.

[16] Drouin, “Cross-Dressing, Drag, and Passing: Slippages in Shakespearean Comedy,” 24.

[17] Abbey Kayleen Elder, "Cross-dressing in Greek Drama: Ancient Perspectives on Gender Performance," Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects (2015): 3.

[18] Elder, 2.

[19] Abbey Kayleen Elder, "Cross-dressing in Greek Drama: Ancient Perspectives on Gender Performance," Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects (2015): 19.

[20] Elder, 12.

[21] Elder, 17.

[22] Elder, 5.

[23] Phillips, Transgender on Screen, 44.

[24] Phillips, Tansgender on Screen, 44.

[25] Phillips, 45.

[26] Phillips, 48-49.

[27] Lindsay Ellis, “Tracing the Roots of Pop Culture Transphobia,” YouTube video, 58:57, February 22 2021, youtu.be/cHTMidTLO60, 15:31.

[28] Ellis, 16:38.

[29] Ellis, “Tracing the Roots of Pop Culture Transphobia,” 17:04.

[30] Ellis, 20:00.

[31] Ellis, 20:27.

[32] Psycho, directed by Alfred Hitchcock (1960; Hollywood, CA: Paramount Pictures, 2020), DVD, 32:23; 01:41:26.

[33] Ellis, “Tracing the Roots of Pop Culture Transphobia,” 19:02.

[34] Phillips, Transgender on Screen, 86.

[35] Silence of The Lambs, directed by Jonathan Demme (1991; Los Angeles, CA: Orion Pictures), https://play.hbomax.com/page/urn:hbo:page:GWl5hUQ77k8LDfQEAAADK:type:feature, 01:35:24.

[36] Ellis, “Tracing the Roots of Pop Culture Transphobia,” 22:43.

[37] Ellis, 25:04.

[38] Phillips, Transgender on Screen, 53.

[39] Drouin, “Cross-Dressing, Drag, and Passing: Slippages in Shakespearean Comedy,” 28.

[40] Victor/Victoria, directed by Blake Edwards (1982; Hollywood, CA: MGM/United Artists, 2012), DVD, 00:32:34.

[41] Drouin, “Cross-Dressing, Drag, and Passing: Slippages in Shakespearean Comedy,” 34.

[42] Victor/Victoria, 01:14:55.

[43] Phillips, Transgender on Screen, 24.

[44] Drouin, “Cross-Dressing, Drag, and Passing: Slippages in Shakespearean Comedy,” 28.

[45] Some Like It Hot, directed by Billy Wilder (1959; Hollywood, CA: MGM/United Artists, 2011), DVD, 30:48.

[46] Phillips, Transgender on Screen, 61.

[47] Amelia Kinsinger, “The Hidden Truth of The Rocky Horror Picture Show.” Brainstorm, vol. 9, (2017): 34.

[48] Kinsinger, 35.

[49] Drouin, “Cross-Dressing, Drag, and Passing: Slippages in Shakespearean Comedy,” 28.

[58] Nick Adams et al, “More Than a Number: Shifting The Media Narrative on Transgender Homicides.” 2018. GLAAD, March 14 2022. https://www.glaad.org/publications/more-than-a-number, 10.

[51] Clarkson, “Terrorizing Transness: Necropolitical Nationalism,” 170.

[52] Natalie Wynn, “‘Are Traps Gay?’ | ContraPoints.” YouTube video, 44:53, ContraPoints, January 16 2019, youtu.be/PbBzhqJK3bg, 03:26.

[53] Wynn, 04:29.

[54] Clarkson, “Terrorizing Transness: Necropolitical Nationalism,” 171.

[55] Clarkson, 171-172.

[56] Clarkson, 168-169, 174-177.

[57] Elder, “Cross-dressing in Greek Drama: Ancient Perspectives on Gender Performance” 15, 33.

[58] Wynn, “‘Are Traps Gay?’ | ContraPoints,” 24:37.

[59] Natalie Wynn, “J.K. Rowling | ContraPoints.” YouTube video, 01:29:44, ContraPoints, January 26 2021, https://youtu.be/7gDKbT_l2us, 01:05:00.

[60] Wynn, “J.K. Rowling | ContraPoints.”.

Author Bio

Julia Federing

is a junior undergraduate at Emerson College in Boston, Massachusetts, currently obtaining her bachelor's in Media Arts Production with a minor in Sociology/Anthropology. They work as a freelance photographer and filmmaker in both the Washington DC and Boston area. They are an on-staff photographer and disc jockey for the music magazine/radio station WECB.fm, and also work part-time as Fulfilment and Inventory Specialist for Emerson College's Equipment Distribution Center. Julia enjoys listening to new music, going to museums and spending time with friends.