Unconventional Mothers and Absent Fathers in Latin American Films

By Arianna Tartaglia

Fairfield University

*See Photo Reference in Appendix for visuals of all images discussed.

Introduction

Complex female characters are few and far between in Hollywood blockbusters, and those representations often come scantily clad as objects for the masculine gaze rather than as figures for women to relate to. The traditional male lens of Hollywood commercial film has influenced the cinematic representation of women, especially when it comes to female character portrayal and development. The end result of these simple, sexual female figures is that real women have internalized this image of the cinematic female, an unrealistic image that does not even begin to represent the myriad of female-identifying people’s experiences. The lack of diverse representations is even worse for women of color, who are hardly ever featured in leading roles.

For people of color (POC), these oversimplified representations are not any better. Media outlets such as Fox and NBC frequently portray POC as caregivers, criminals, maids, or cooks, all low skill jobs that are not a true reflection of reality. In the way that these roles are not reflective of reality, highly visible film awards are hardly ever awarded to POC. One quarter of Latinx speaking roles were for criminals from 2001-2018.[1] Only three percent of lead roles in this period were played by a Latinx actor in the same period, 2001-2018. Only four percent of directors were Latino, and of those four percent, only one single director was a woman, Patricia Riggen.[2] Not surprisingly, no Latina directors have ever won the Oscar for best director. However, Oscar-nominated films repeatedly recognizing white, male directors does not mean that there is a scarcity of Latin American films directed by women.

Throughout the course of 91 years of the Oscars, only one female director has ever won the prize. Katheryn Bigelow won in 2010 for her critically acclaimed film, The Hurt Locker, which won six Oscars including best picture and best director. While Bigelow’s achievement was a breakthrough for women directors, an argument can be made that the film itself is built off of previously existing norms and draws on a long tradition of masculine cinematic tropes and language. Bigelow shattered the glass ceiling in one way by being internationally recognized for her work as a director but used an existing film prescription that upholds traditional gender norms. This film will be used to examine the representation of fatherhood in relation to gender performance as male characters are more likely to be shown independently of their families. The film exemplifies his struggle outside the home, fighting for his country, a typical male portrayal, including that of heroes contrasts h women are portrayed in cinema.

The four films selected to act as foils to The Hurt Locker are about women and directed by women, featuring female protagonists who raise their children as single mothers or within an untraditional family unit. These films illustrate a reality outside of the grand narrative of family life that shatters idyllic perceptions of the necessity of heteronormative gender roles within families. These four films, Dólares de Arena, El Techo, Pelo Malo, and Mi Amiga del Parque serve as counterpoints to such ideas These films highlight the assumed centrality of motherhood to the performance of women and repeated depiction of motherhood within cinema. These non-commercial, non-Hollywood films expose the previous invisibility of the process of becoming a mother and the assumed responsibility of the children by mothers. These films break down the notion that motherhood is necessary for the performance of the female gender and if female characters do become mothers, the films question the notion that it is a purely glorious and gratifying experience. In addition, traditional methods of childbearing and rearing highlight how women are systematically denied agency once they are in charge of children in a way that men are not. Childcare duties are typically relegated to women by default within the home, meaning men can go about working, drink at the bar, or flying overseas for multiple tours of duty without worrying about who will take care of the children, so their agency is not restricted by the children as it is for women.

I. Breaking the glass directors’ ceiling? Katheryn Bigelow and The Hurt Locker

In 2010, the Academy awards shined a spotlight on a woman director, Kathryn Bigelow for her film The Hurt Locker, a momentous win for women directors and equality activists fighting against the hegemonic power of men in film. Bigelow won the Academy Award for Best Director and the film won the Academy Award for Best Picture among many other awards from groups like the British Academy of Film, Television Arts and the Writers Guild of America. Despite all the awards and praise for a woman finally winning the award for best director, The Hurt Locker does not challenge gender roles, nor offer a different representation of women.

The stereotypical presentation of fatherhood and career in The Hurt Locker stands in stark contrast to the presentations of motherhood in the four Latin American films used. The Hurt Locker tells the story of William James, a bomb squad specialist who lives off of adrenaline and bravery to disarm bombs across Iraq. The viewer follows his escapades, flirting with death and defiantly disobeying orders to protect and serve, or perhaps to prompt an adrenaline response. At the end of Staff Sergeant James’ tour, he returns home to his wife and baby where the viewer sees him taking part in civilian life; cleaning his gutters, cleaning mushrooms in the kitchen sink, and then playing with his baby. The maleness of protagonist William James is not dependent on his performance of fatherhood, but rather on his sacrifice as a soldier. The male protagonist is both an honorable soldier and an absent father, but his faulty commitment to his son and wife is not how the viewer is asked to judge him. His absence is justified by his job, a standard that does not apply to mothers, as this research explores.

The Hurt Locker’s heroic protagonist William James is an example of the performance of gender, which Peberdy describes as an artificially constructed version of gender used in cinema to normalize these representations. The replication of these constructions perpetuates this singular idea of correct masculinity and leads men to see themselves in these artificial constructions[3] In The Hurt Locker, the almost all-male cast enforces this notion, as the men in the film performing similar kinds of hyper-heteronormative masculinity like other men in their command. The maleness of James is then artificially constructed through his war experience and backed up by his status as a father, which confirms his virility in image 1 below.

In image 1, the viewer watches James play with his son who remains nameless throughout the film, indicating a lack of connection between father and son. The baby does not define James as a character but is instead used to illustrate some facet of normalcy and consistency in his life; this would be incredibly different for a female character, where the baby would define her life. The namelessness also prevents the viewer from making a connection with the baby, marginalizing James’ entire family. As James talks to his son, he has an epiphany that his one true purpose is to serve in the armed forces as a member of the bomb squad with the next scene cutting to the helicopters landing in Iraq again where James exits the plane for his next tour of duty. This epiphany occurs in Image 1, where James is distanced from the viewer, suggesting a lack of intimacy and connection with his family even though he is in his own home. James and his son are in the center of the frame, but most of the space is occupied by walls, creating a sense of claustrophobia for the viewer and illustrating James’ feelings of claustrophobia when confined to his own home.

In the following few scenes with his son, the two characters are not shown in the same frame together but rather through cut scenes where the son followed by James appears, creating more distance between the two. This usage of cinematic language means for how the viewer sees and subsequently judges James as a man and father. The viewer understands that his call to serve pulls him back to Iraq and that he is doing something noble by serving his country. The fact that James’ family is hardly shown for more than ten minutes in the whole film suggests that they are almost inconsequential. The viewer almost forgets that he has a family and that he is a father that played with his baby for less than three minutes in the entire film. However, his behavior as a father is inconsequential to how he is seen as a soldier. Bigelow uses this language of maleness to justify James’ decision, which rests on the gendered public/private binary of leaving the private sphere for the public sphere- which receives more attention and is paid. In other words, James is a hero independent of his family life. Fatherhood does not define James, his career does. His wife takes care of their child alone and is only a fraction of his story, again illustrating how Hollywood marginalizes female characters and the weight of motherhood.

The success of this film at the Oscars and Bigelow’s breaking of the glass ceiling is a contradiction of sorts; while celebrated for breaking the gendered glass ceiling in winning the Oscar for best director, the representation of the gendered character roles within the film do not challenge the patriarchal roots of Hollywood film. Bigelow’s film relies on the masculine gaze to make James a hero on the battlefield. This idea of heroism is supported by James’ call to serve being so strong it repeatedly pulls him away from his family, enforcing the notion that a man’s place is outside of the home. The film continues the recipe of making home life, childrearing, and domestic responsibilities invisible and female with his wife occupying the role of caregiver and homemaker in the private sphere, while the male protagonist gains recognition and fame in the public sphere as a soldier and ultimately an absent father. This argument is not to say that soldiers should not be honored for their service, but rather to point out how ingrained these notions of gender are, dividing male and female visibility as seen in From Here to Eternity and American Sniper to the point that the viewer does not even question the absence of a husband and father because of the assumed omnipresent and self-sacrificing mother figure.

II. A Look at Four Latin American Films

The way that The Hurt Locker portrays the performance of the male gender and the role of the father is another example of the visibility of maleness within cinema. Films like this are seen, awarded, and visible in ways that films about women are not. Some independent films challenge the traditional relationships between mother and child, but these films do not receive the same kind of visibility. The Latin American films, Dólares de Arena, El Techo, Pelo Malo, and Mi Amiga del Parque were chosen because their representations of motherhood in different stages illustrate how motherhood is still deeply rooted in gendered inequality despite changes in the role of women in society, highlighting different representations of motherhood on screen. The films follow a chronological progression of motherhood with Dólares de Arena and El Techo offering representations of pregnancy. Mi Amiga del Parque provides an intimate portrait of postpartum depression and the struggles of mothering during the infant’s first year, while Pelo Malo illustrates a dystopian view of motherhood with older children. Each of the films depict an unmasking of motherhood, such as the exposition of the loneliness of motherhood in Mi Amiga del Parque, rejecting typical saint-like representations of motherhood, showing the omnipresent mother figure that is taken for granted in films like The Hurt Locker. The objective of this film analysis is to quantify the cultural phenomenon of motherhood and the fusion of female identity with the role of motherhood as the performance of a joint female-mother identity unique to mothers. These films make visible the work that Bigelow erases during The Hurt Locker, by showing how women shoulder motherhood by themselves, without the same heroic recognition.

III. Motherhood: A Theoretical background

The theoretical concept of the grand narrative of motherhood illustrates how these films interrupt the Hollywood narrative of invisible female work and seek to present another point of view of motherhood outside of the white, middle-class nuclear family representation that dominates the screen. The grand narrative is defined as “a story scripted by some authority—whether it is an academic, a policy-maker, or the apparent consensus of a majority of people—that is ‘so pervasive, so taken for granted, as the only valid story’ (xxv) that it becomes a socially constructed truth”, with Lauren Johnson’s counter-narrative provided another kind of valid story.[4] The grand narrative in this case would be the stereotypical depiction of motherhood, nuclear family living in the suburbs with a stay at home mom who dedicates her life to taking care of her children while her husband works 9-5 at an office job. This narrative excludes almost all other experiences of motherhood. Johnson, a psychologist, has published work on alternative female narratives to unexpected pregnancy in order to create literature that reflects positively on unplanned pregnancy, in contrast to the traditional idea that single women who experience an unplanned pregnancy are at fault without a partner. Johnson’s video interview work uses only a few subjects from Canada who were all middle class and white, which gave them more financial resources to take care of their child and use expert mothering like child care. Johnson proposes that her objective was to offer an alternative narrative to the ‘grand narrative’. The grand narrative of male dominance helps explain the hyper-visibility of Oscar-winning films like The Hurt Locker and therefore, Hollywood’s erasure of the struggles of motherhood. These Latin American films present counter-narratives and grand narratives at the same time, recreating the complexity of motherhood that exists in the real world, rather than the one-sided Hollywood representation.

In order to understand representations of motherhood, Andrea O’Reilly argues that motherhood has been consistently defined by patriarchal ideals rather than by real practice or routed in testimonies reflecting mothers’ experience. O’Reilly outlines three separate concepts of the performance of motherhood, as an “experience and role”, “institution and ideology”, and “identity and subjectivity”.[5] These concepts can be seen in each of the films that will be analyzed, but I will focus on the experience of motherhood that is captured on screen and the identity that comes attached to the motherhood portrayed.

O’Reilly proposes the “ten ideological assumptions of patriarchal motherhood”, which identifies different areas in which the women protagonists in these films experience the pressure of patriarchal motherhood.[6] The ten assumptions categorize the different conventions applied to motherhood that have changed the ways how women are judged. The assumptions dissect the behavior of the mothers in the chosen films and illustrate the difference between patriarchal discourse surrounding motherhood and realistic discourse from women filmmakers. These assumptions break down traditional practices and define the patriarchal influences that drive that performance. It is easy to say that motherhood is the most natural, instinctive, and basic act, but at a closer look it is not divorced from politics, economics, or philosophy as O’Reilly explains through the ten assumptions. Her assumptions aim to divorce what we have come to know as motherhood from its societal influences and illustrate the shaping of motherhood by outside pressure. If these assumptions shape motherhood in the real world, then they also influence the depiction of motherhood in cinema and support the Hollywood version of motherhood.

Dólares de Arena, El Techo, Pelo Malo, and Mi Amiga del Parque also present a wider representation of motherhood beyond the traditional ‘good mom’ character found in films like The Blind Side or Steel Magnolias. O’Reilly defines mothers outside of this accepted sphere as those who “by choice or circumstance, do not fulfill the profile of the good mother—they are too young or too old, or they do not follow the script of ‘good’ mothering— they work outside the home and live apart from their children” and are therefore ‘unfit’ mothers in need of rectification, since they fail the assumption of idealization.[7] In this case, the ‘bad’ mother is not capable of performing motherhood as it ‘should’ be performed according to patriarchal motherhood norms.

None of these concepts like age, work, or living situation apply as stringently to the father figure. To consider someone to be a ‘good’ father, the qualifications are essentially limited to showing up and playing with your child like what James does in The Hurt Locker. In almost all four Latin American films, with an exception for Dólares de Arena, the father figure is physically absent, placing the entire experience of parenthood on the mother. The strict ideal of motherhood as self-sacrificing is not applied to male characters. We can see this double standard in Bigelow’s award-winning film. The protagonist James does not have to choose between his family and his military career, he picks his career and leaves the caretaking to his wife at home, yet The Hurt Locker won best picture. Less than perfect male characters can exist, can be protagonists, and are even celebrated! These characters take center stage in a variety of films, like The Wolf of Wall Street and American Sniper.

The performance of motherhood is also separated from the performance of gender, despite the fact that they are closely linked. As Pagnoni Berns explains, “a subversive act can take place within performative acts that rupture the daily repetition of gender construction,” but these acts only affect the person who disrupts the societally accepted performance[8]. In terms of motherhood, however, any disruption of accepted mothering behavior involves two subjects, the mother and the child. Female characters are not afforded the same flexibility that male characters are with their roles as mothers being central to the value judgement of characters. The women protagonists in these films are influenced by society because of the effects that their behavior will have on their children.

The weight of childcare duties as real work instead of a self-sacrificing act of inherent natural gender practice is not represented in Hollywood film. The four selected Latin American films show how childcare is real work by illustrating how mothers sacrifice, fight, and suffer while taking care of children on their own. For example, Mi Amiga del Parque shows how Liz is consumed by taking care of her newborn baby on her own. This phenomenon of working visibly outside and invisibly inside the home is best described by Danae Diéguez as the “doble jornada laboral”[9] in which both women’s roles and representations of women’s roles experience double the work that a man who only works outside the home does, but yet are limited in terms of agency[10]. This unequal division of labor is also indicative of the performance of the female gender and why these films emphasize women for the act of mothering. James is not subject to the doble jornada because he is not home at all, leaving his wife with all external and internal labors while he is away. Therefore, The Hurt Locker falls into the trap of leaving motherhood invisible, in the shadow of a man, without celebration or recognition. In the next section, these theoretical concepts will be used to explore representations of pregnancy in Dólares de Arena and El Techo.

IV. Pre-Motherhood in El Techo and Dólares de Arena

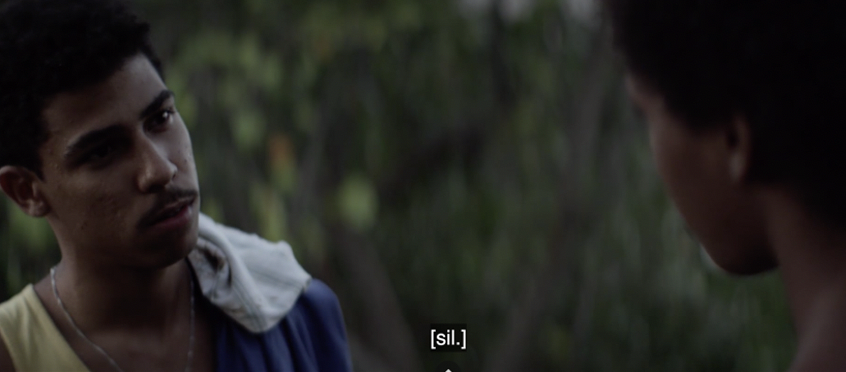

El Techo tells the story of Anita, Yasmani, and Vito, three young adults living in Cuba. None of the protagonists have mothers in the film, Yasmani and Vito’s mothers died, and Anita’s is in the United States. Anita is pregnant and refuses to tell her mother. The director, Ramos Hernández, creates a dialogue in El Techo between Anita and her unborn baby, and the impending state of Anita becoming a mother in order to re-write preconceived notions about motherhood. Anita feels attached to her child and starts preparing by buying baby clothes without having any of the other ‘requirements’ of having a baby, such as a husband or house. In fact, there is no semblance of a nuclear traditional heteronormative family in El Techo as all of the main characters are missing one or both of their parents. Anita herself does not believe that both parents are necessary in childrearing, when Yasmani (center) asks her about the father of the baby she responds by saying:

In images 2 and 3, Anita completely rejects the grand narrative that supports the idea of the traditional heteronormative nuclear family by expressing her antipathy towards present fathers. Her own journey to motherhood is a counter-narrative. In these images, the viewer can tell that Anita is confident in her words with relaxed body language, shoulders down and legs tucked under her as seen in the image 2 above. She makes eye contact with Yasmani as she says that she does not care about the father of her baby, illustrating her confidence in her words. In addition to this, her baby bump is clearly visible in the shot emphasizing the fact that Anita is not hiding her baby or shameful about being a single mother, except when it comes to her own mother. Through Anita’s body language and words, it is evident that Anita accepts her position and is confident in her ability to be a mother without a father.

However, Anita’s performance of the female gender and her confidence in her decision falters when confronted with another female presence. In images 2 and 3, Anita is alone with Vito and Yasmani and has no problem expressing her feelings on motherhood without a father. Anita is beyond the point in her pregnancy that most people tell family and friends that they are expecting, but yet Anita has not told her own mother about her baby. If motherhood is essential to the performance of femininity, it seems counterintuitive that Anita refuses to tell her mother. When she is asked by Vito about if her mother knows, Anita responds saying:

Image 4 seems to contradict the idea that Anita is confident in her journey to motherhood if she is not comfortable explaining her situation to her own mother. She does not hide the fact that she is pregnant to those around her, but single motherhood does not fit in the grand narrative as Anita is unable to cross the communication barrier between herself and her mom. There are a few explanations for her attitude. Anita’s mother believes in a traditional family unit, and would chastise her and thus destabilize Anita’s confidence in her decision, or her mother raised her without her father and feels as though it was the wrong decision.

This disconnect between Anita’s attitude and lack of disclosure to her mom suggests a feminine judgement of motherhood that is more critical than male judgement. Despite modern trends, change and equality have not overcome traditional ideas about the division of labor between men and women and the roles they both play within the home. A kind of shame and guilt persists for single mothers and unknown fathers because they exist outside of the grand narrative. In the shot above, Anita is not looking at her companions, but looking into the distance, while articulating what she would say to her mom. This suggests that female judgment on motherhood is more intense than male judgement.

This does not mean that men are excluded from influencing the perception of gender with male bias. In El Techo, Anita spends most of her time hanging out with men. It is significant then that the viewer does not find out that her baby is a girl until almost half way through the film, and it is revealed at a very tense moment in the film while Anita is surrounded by males. While showing her ultrasound to Vito, Yasmani, and the clothes merchant, the merchant insults how the baby looks in the ultrasound. When Yasmani says the baby could be his, the merchant argues that it could not be because of how ugly ‘it’ is. When Anita hears this, her immediate response in Image 5 shows her need to gender her baby. This indicates her feeling of connection to the baby and thus explains her emotional response to the merchant’s mean-spirited words. In the image 5 above, her mouth is open, looking dead at the merchant as she angrily declares that ‘it’ is not an ‘it’ but a girl. Her tone as she says this is commanding and defensive. This suggests that she does feel the need to defend herself and her baby against the judgment of men. Despite Anita’s confidence in her own decision on motherhood, Images 4 and 5 indicate that negotiating female identity and single motherhood is difficult because it lies outside of the grand narrative. Anita’s counter-narrative shows that even if a mother is confident in her own ability, there is a consistent social scrutiny from friends, relatives, and strangers questioning the validity of her motherhood that discredits her narrative.

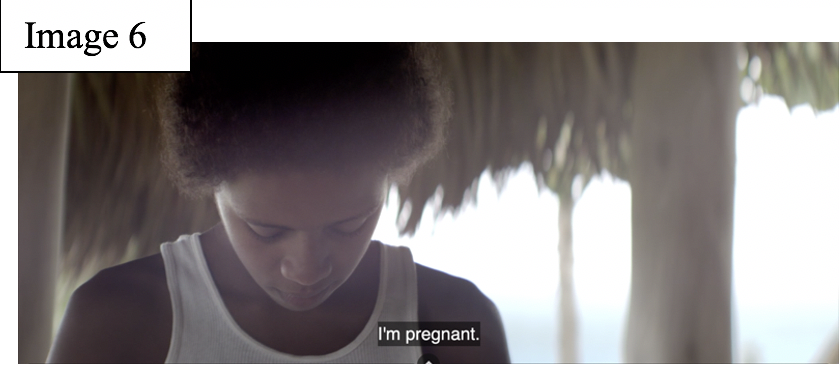

In relation to Anita’s journey, in Dólares de Arena, Noelí also has no relationship with her mother who lives abroad and becomes pregnant while in a nontraditional family situation. Noelí has relationships with tourists, both men and women, in order to support herself and her boyfriend. She receives both money and gifts from them, as the viewer sees at the beginning of the film where the Frenchman she is seeing gifts her his chain, only to have her boyfriend pawn it immediately after. This is only a glimpse at her relationships however, as throughout the film she develops a deep relationship with Anne, a tourist, lesbian, and French national who crosses the line between mother figure, caretaker, and lover. Noelí’s relationship with Anne is unequal, but Noelí discloses her pregnancy to Anne first in image 6.

Her lack of eye contact in image 6 and the fact that she is the only person in the frame though she is talking to Anne suggests that disclosing this is more about Noelí confronting her pregnancy as a reality than about telling Anne herself. The viewer learns early in the film that Noelí previously had one abortion indicating that Noelí may not have been ready to be a mother then but is ready now. Her choice to disclose to a woman first suggests a bond between women in understanding the weight of motherhood and the implied ties between all women who perform femininity and motherhood.

Anne is accepting of her pregnancy even though she has no relation to the child other than her emotional connection to Noelí and takes her to the doctor after she is in a motorcycle accident. At the doctor’s office, the doctor performs an ultrasound where Anne asks: “can we have pictures of this, for memory?”

In Image 8, the viewer can tell that Noelí is looking back at Anne after she asks for the picture of the baby in image 7, smiling towards Anne. Her smile indicates the happiness she feels from the acceptance of her pregnancy and the bond between herself and Anne over the experience of motherhood.

However, while Anne and Noelí openly discuss the pregnancy, Noelí does not disclose the pregnancy to her boyfriend, which he confronts her about. Her avoidance suggests that she knows that when she discloses to him their relationship will change, and he will have more control over what she does. He benefits from the relationship that Noelí has with Anne because she makes money and supports both of them, since he does not have a job. She maintains heteronormative and homoerotic relationships at the same time, and still ends up being saddled with traditional expectations of motherhood once he learns about the baby. He confronts her in image 9 and in image 10:

This confrontation is wholly focused on him. In image 9, Noelí is not on screen, but the intensity of his gaze is clearly looking at her. The camera angle is tilted up slightly as if he’s above the viewer, suggesting that he has a power over this situation because he is a man. The dialogue also indicates that Noelí has disclosed to others besides Anne since ‘people’ plural are talking. In Image 10, Noelí is in the foreground and out of focus, while her boyfriend is in focus and maintaining consistent eye contact while asking about the future of his son. Here, the performance of motherhood shifts from being entirely about Noelí and her child to a responsibility to her boyfriend who assumes one, that he is the father, and two, that the baby is a boy. The viewer knows that the baby is a boy because the doctor tells Noelí earlier in the film, but it is unclear if her boyfriend knows this since he did not even know that she was pregnant. This assumption illustrates the gendered bias that he brings to their relationship that helps maintain the performances of masculinity and femininity. It is not about Noelí leaving, but now about his son leaving. In this way, her relationship to her boyfriend has now shifted from romantic to familial, she will be the mother of his son, and therefore her performance of female gender is tied to this child.

At the end of the film, Noelí chooses to remain in the Dominican Republic with her boyfriend rather than going to France with Anne. Noelí gives up the opportunity to raise her child with Anne in France and with considerably more money than she has. There are several factors that bring about this decision. First, Noelí and her boyfriend love each other, which is the most obvious, but in choosing to stay with her boyfriend she also chooses to replicate heteronormative family structure and uphold traditional performances of femininity and masculinity. Her choice then reinsures the legitimacy of her motherhood and shows the ways in which the fathers of children can exercise agency over the mothers through biological ties and traditional parental roles.

V. Beginnings of Motherhood: Mi Amiga del Parque and Pelo Malo

Mi Amiga del Parque tells the story of Liz, a new mother to baby Nicanor living in Argentina. Like Anita and Noelí, Liz’s mom is not in her life. Nicanor is young, and the viewer learns early in the film that Liz is having trouble adjusting to motherhood, as she is shown falling asleep while giving him the bottle. The next scene cuts to her hiring Yazmina to help Liz with the baby and house chores. As Liz tells Yazmina about how she is “a little overwhelmed” and her “husband travels a lot”, Yazmina relates her own story of motherhood to Liz:[11]

In images 11-13, the camera is focused on Liz even though Yazmina is talking, and she keeps her attention focused on her son. The viewer can tell that Liz is listening to Yazmina’s story due to her face going from relaxed in image 11, to slightly more concerned in image 12 with her brown slightly furrowed and her mouth down turned in the corner, to even more concerned in image 13 with her brow fully furrowed. Her concern over Yazmina’s story shows her sympathy for Yazmina, but since images 11-13 are focused on Liz the viewer is meant to understand that Liz’s reaction to this story is more important than the story itself. Her sympathy is not reciprocated by Yazmina, who, after telling her story, tells Liz that:

Yazmina’s words invalidate Liz’s own struggle with motherhood and illustrate the intensity of judgement that mothers receive from other women. Here, the male gaze is not just held by a man but also perpetuated by women. Yazmina has come into Liz’s home at a moment where she needs love and support, but instead criticizes Liz without offering any judgement for the absent husband and father. Yazmina’s lack of sympathy illustrates the naturalization of motherhood, or in other words, that motherhood is an inherent quality that women possess and not something learned through experience[12]. From her perspective, Yazmina had a much harder experience and therefore Liz’s ‘excuse’ is not good enough to excuse her lack of ‘mothering’ skills, the skills that Yazmina considers essential. The camera shift in image 14 reinforces this idea: the viewer now sees Yazmina, holding Liz’s baby who stopped crying as soon as Yazmina picked him up. In this way, Yazmina not only invalidates Liz’s performance of motherhood verbally by comparing it to hers, but also physically by instantly calming the baby without appearing to do anything.

However, Yazmina is not the only character in the film to judge Liz’s performance of motherhood. Liz is repeatedly told how to be a good mother by other men in the film, contributing to her frustration at her perceived ineptness and exemplifying how the performance of motherhood is constantly under scrutiny in a way that masculinity is not. When Liz visits the doctor for Nicanor’s checkup, she expresses her concern to the doctor about not knowing what to do for her son, he responds by saying that even in poor families, “if the mother plays with her child, talks to him, supports him” then “that child is protected”, but it puts all of this responsibility on the mother.[13] Since Liz is the only parent at the doctor’s office, it is possible that the doctor said ‘mother’ because the father is not present. It can be speculated however, that the doctor, who is a man, says ‘mother’ because he believes that only a mother can do this. During this scene, the camera is focused on the doctor and the viewer does not get to see Liz’s reaction until he’s done talking. By denying Liz an opportunity to respond on screen, or for the viewer to even see her reaction, this scene supports the idea that the full burden of childrearing falls on mothers and they are not given a voice, nor the agency to change their situation.

In fact, the doctor is not the only male character to give Liz advice on parenting or comment on her performance of motherhood, which enforces preconceived notions of motherhood without having any experience that would inform their critique. These instances illustrate the masculine assumption that motherhood is inherent to women. The first instance of a commentary on Liz’s performance of motherhood comes from her friend (who she later cheats on her husband with) and he asks her how breastfeeding is going, a fairly personal question to ask a new mother, especially as a man. In image 15, Liz is still smiling from the beginning of the conversation while her friend is smiling as he asks her the question. Here, the spectator can see both of the subjects, equally sharing the frame as they walk and talk. Once Liz confesses that she is struggling with breastfeeding and cannot do it, the camera angle changes in image 16.

Liz starts crying once she confesses that she cannot breastfeed Nicanor as she places her head in her hand, avoiding eye contact with her friend. Image 16 hearkens back to the scene where Noelí finally comes to terms with her pregnancy as the language in this scene suggests a similar feeling. Liz is finally confronting her shame in not being able to breastfeed out loud, but instead of having this moment with another woman, like Noelí and Anne, she has it with a man, who does not understand the reality of motherhood in the way that Liz does. Breastfeeding is not as natural as one would think, and many women experience some difficulty, but bottle feeding is not part of the grand narrative of motherhood and has somehow come to represent substandard mothering even though it has no impact on the growth of the baby.

Similar to Anita and Noelí, Liz is also missing her mother, which means that she does not have a close female relationship that she can depend on as she learns to be a mother. Yazmina is the first to point this out in Image 17. Yazmina mentions this after she tells Liz that she is complaining just to complain in Image 14, so this seems to the viewer that Yazmina is justifying her insult to Liz by blaming her mental state on the fact that neither her mom nor her husband is around to help her.

By allowing the camera to capture the internal struggle, postpartum depression, and loneliness of new motherhood, the viewer sees how these socially acceptable comments that Yazmina makes are exceptionally cruel and hurtful to Liz and would be to all mothers. Liz’s loneliness that comes with motherhood without her own mother and husband is similar to the experience of many new mothers who are alone with their babies. This goes directly against the traditional romanticized cinematic representation of motherhood. The viewer finds out later that Liz’s mother died within the last year while she was pregnant, understanding why she has no parental support. This scene exemplifies the loneliness that mothers can experience that is systematically undocumented in media in order to support traditional notions of motherhood within media. Despite Liz’s struggle, the film makes her love for her child irrefutable, with how she worries about what is best for him and always thinks of him first. A mother not loving her child seems like an impossible story to tell, but Pelo Malo contrasts Liz’s story of self-sacrifice with a dystopian view on motherhood.

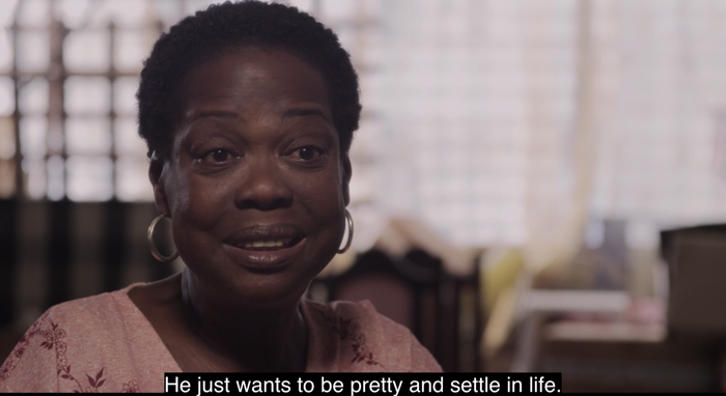

Pelo Malo tells the story of Junior and his mother, Marta who live in the public housing of Venezuela. Marta was a security guard until she lost her job due to an unexplained incident. Unlike the previous films, Marta does not treat her oldest son, Junior with love and affection, but rather dislikes him in a relationship dynamic that is almost never portrayed in Hollywood films. The viewer learns a lot about Junior at the beginning of the film: he likes to dance, he wants to straighten his hair, and he wants his picture taken as a singer. However, his mother does not approve of his behavior and catches him dancing in the stairwell of their building, later asking him about it and forcing him to dance with her until he runs away. From this scene, it is easy for the viewer to conclude that Marta does not like her son for who he is, nor does she accept him. However, when Junior’s grandma offers to take Junior and raise him Marta refuses, responding in image 18 below.

Her reaction is surprising, considering that a few scenes before the viewer watches her yell at Junior. Image 18 shows Marta in the middle of the frame, looking at Carmen, Junior’s paternal grandma, and speaking. The intensity of her gaze is amplified by her lowered chin and the light creating dark shadows below her eyes, drawing the viewer’s eyes to hers. This image cements the viewer’s understanding of their relationship, Marta dislikes her son but still wants him to live, at least in this moment. In the next two images, 19 and 20, Carmen calls Marta out for why she dislikes Junior:

Here the viewer comes to understand why Marta had such an issue with Junior dancing before, because he wants to be “pretty” rather than handsome while Marta has an issue with these perceived feminine traits. Carmen seems to be accepting of who Junior is as seen in Image 19 where she almost smiles while talking about what Junior desires to be. Her smile falls in image 20 as she stares at Marta, expressing her judgment of Marta for not accepting her grandson for who he is. Images 18-20 illustrate the tension between the two women over Junior, and Carmen’s defense of Junior makes the viewer critical of how Marta treats him. Carmen’s offer to take Junior seems appealing, but something keeps Marta from accepting, whether it be selfish motives or some innate attachment to her child.

After Marta, Junior, and the baby go home, Marta continues her quest to return to her job as a security guard. Her occupation fuels some of her perceptions about men, as all the guards she sees as she revisits her office trying to recover her job are all men. This affects how she treats Junior, and the expectations that she has for him. Marta will go as far as to follow Junior into the bathroom to enforce these expectations, as images 21 and 22 show:

Image 21 highlights the fact that Junior is a young boy, his feet do not even reach the ground as he sits on the toilet. He may be sitting because he needs to do more than urinate, but when Marta finds him sitting on the toilet, she tells him that “men do not pee sitting down” and then continues to bang on the door with the palm of her hand and scream at Junior to get out of the bathroom in image 22. These images show the lengths that Marta will go to in order to impose socially accepted ideas of the performance of the male gender on Junior, violating his privacy while he uses the bathroom just to make sure that he pees ‘correctly’. She does this in a public bathroom too, showing that she has no problem embarrassing Junior in public just for this purpose. Not to mention, tying someone’s gender identity to their position while urinating is bizarre. Here, Marta shows yet again her distaste for her son because he continually rejects what she believes to be the correct performance of gender.

Part of the plot of the film centers around a picture that Junior and his girl neighbor keep planning to take. Both of them need a passport photo for school, but the girl wants her photo taken as Miss Venezuela and Junior wants his picture taken as a singer with straight hair, so he asks his grandmother to make him a suit and straighten his hair since his mother will not let him do anything with his hair. His neighbor suggests that he should get his picture taken as a soldier in the Venezuelan army for his mom (image 23). The fact that even the neighbor knows about Marta’s dislike of her son’s character indicates that she is public about her dislike, just as she was in images 21 and 22. The subtitles in image 23 translate the girl’s words in a loose manner, something I find important to point out in order to understand the depth of Junior and Marta’s relationship. What the girl says in Spanish is that he should get his photo taken as a soldier “para que tu mamá te quiera”, which also translates to “so that your mother will love you”, a much stronger statement on the public knowledge that Marta rejects her son for who he is.[14] Here the neighbor suggests that if Junior conforms to traditional gender roles that his mom will love him, but if he does then Junior has to reject who he really is. What is even more remarkable about this scene is the common knowledge that Marta does not love her son, which goes against the classic portrayal of loving, self-sacrificing mothers described earlier in this paper.

While Marta spends most of her time in the film yelling at Junior for how he uses the bathroom and for brushing his hair, there is one moment when she questions herself at the doctor, and if Junior’s female tendencies are her fault. Marta goes to the doctor and asks him if Junior is gay, and then blames it on herself for not holding him enough. The doctor responds to Marta in a similar way to how Nicanor’s doctor responds to Liz in Mi Amiga del Parque, suggesting that she spend more time with her kids. The parallel of two male doctors advising mothers who are questioning the success of their mothering is indicative of the judgement that women receive from men and that women are used to looking for external acceptance for their work. Mothering becomes a public discourse, even though the majority of the work is completed by the mother alone. Both Liz and Marta are worried that they have somehow messed up their children, despite the fact that their children are healthy and for the most part, happy.

The one point of tenderness between Marta and Junior in the film occurs after he tries to ‘fix’ his hair with mayonnaise. When Marta discovers him, she screams and washes his hair in the kitchen sink. When Junior goes to bed, Marta comes in and tells him that he does not have bad hair. In Image 24, the viewer sees Marta gently stroking Junior’s hair while he lays in bed, looking up at her. Marta’s expression is neutral for once, she is not frowning or baring her teeth, and her voice is soft as she talks to Junior. The soft lighting of Image 24 creates a kinder atmosphere than in previous shots, and the closeness of Marta and Junior suggest a moment of intimacy as they both address what they see as the common problem, Junior’s hair. In this moment, however, Marta accepts Junior’s hair for what it is, showing that despite the complexity of their relationship there is some element of connection between mother and child.

This connection could mean love, but it does not mean complete acceptance. At the very end of the film, Marta starts packing Junior’s stuff to send him to his grandmother’ home, seemingly permanently. Marta has undergone a change of heart in image 18, where she refused to leave Junior because she didn't want him to get shot. Junior starts protesting and trying to pull his stuff out of the bag because he does not want to go back to his grandmother after a misunderstanding believing she made him a dress, vehemently protesting because boys do not wear dresses. As he begs her to stay, he asks his mother if he can stay if he cuts his hair, and Marta pulls a pair of clippers that she bought before her work out of her purse and puts them on the table. In response to this, Junior says:

The exchange in images 25 and 26 goes against everything the viewer expects from a mother. Junior holds the clippers in the bottom left corner of the frame and looks directly at his mother, telling her that he doesn't love her. The fried plantains that he asked for and Marta made are also in the bottom corner near his hand, highlighting the juxtaposition of the razor that he hates and the plantains that he loves. Marta validates his sentiment by responding and saying she doesn't love him either. Here, Marta rejects the very thing that mothers are always supposed to do, loving their children for who they are.

Being a mother is not central to Marta’s performance of the female gender as Junior is no more than an obligation to her. The viewer can sense this in image 26 from Marta’s body language; her head is tilted slightly, her mouth is straight, eyebrows neutral, and eyes looking right at Junior. Her lack of emotion makes the statement more powerful as evidenced by her truthful response rather than speaking out of anger. Marta occupies the majority of image 26 with nothing else in the frame unlike Junior in Image 25. This focus on her suggests that this is her true sentiment, that there is nothing influencing her words other than her true feelings, going against everything we are told to believe about the joys of motherhood.

Conclusion

To compare Pelo Malo to The Hurt Locker, audiences would judge Marta differently if she up and left Junior and the baby to join the army. Marta’s work as a security guard, a male dominated field, has influenced her perception of how males must behave. The viewer judges Marta for her abrasive treatment of Junior and sympathizes with him because his mother does not accept him for who he is. James does not even see his child, since he has reenlisted in the military. The viewer is not asked to judge James and may not judge him for not being there for his family. His role as a father is glossed over because it is not central to his worth. Marta’s role as a mother is not, but the viewer judges Marta for her actions and for her lack of ‘motherliness’. These representations of parenthood show striking contrasts between how each parent is represented and what characteristics are assigned to each gender.

There would be a different reaction if Anita and Noelí were not excited about their babies and instead dreading their arrival. Viewers would feel like something was wrong with them, as if they were unfit to be mothers. However, James is seen playing with his baby for three minutes of a 131-minute film, only to leave again, and is not considered to be an unfit dad. He dreads being at home and dreams of the battlefield instead of his loving wife and little baby. This film reminds audiences that family and children belong in the woman’s realm while the man’s is outside of the home. It is assumed that these babies will become everything to Anita and Noelí, the new center of their life, but James’s baby is clearly not the center of James’s life because his career is the center of his life. These uneven expectations highlight the entanglement of the performance of female gender and motherhood in ways that the performance of the male gender and fatherhood are not.

The characters Liz and Nicanor in Mi Amiga del Parque show the other side of parenting while the father is away. Liz is consumed by her responsibility to her baby, barely spending any time with friends and being constantly criticized by others for her motherly decisions. As James enjoys the company of his fellow officers and occasional check-ins with his wife, viewers can see the toll that it takes on the other end by observing Liz’s loneliness. This shows the agency that men are given, in comparison to women, who assume all responsibility for their children. Mi Amiga del Parque also illustrates the disparity in how we judge women and parenting in comparison to men. Liz receives harsh criticism from Yazmina, but no comment is made on the absence of her husband. The same goes for James when he is not judged for not supporting his wife, nor does he receive any criticism from those around him. Here again the incredibly different standards for mothers and fathers are made evident through these two films.

The four Latin American films analyzed provide alternative representations of motherhood that go against the single story featured in the grand narrative. The diverse illustrations of motherhood remind the viewer that there is no ‘right’ performance of motherhood or of the female gender, but only preconceived ideas that stem from societal expectations and create an illusion of ‘correct’ mothering. Since these films were created outside of Hollywood commercial cinema, they reflect a wider variety of experiences while also exposing the truth of motherhood that hides behind the grand narrative. This truth is that women are underrepresented, less respected, discredited, and typically erased in Hollywood films, making it easier to undervalue and under-reward women who work in film.

Of the women who work in film, the only one to win best director worked with male language and used a grand narrative in her film. Even though many touted Bigelow’s success in breaking the glass ceiling as a sign that society was finally accepting and awarding female achievement, her film actually does the opposite by ignoring the inherent inequality in the protagonist’s family life and erasing all the work that the female character does to keep the James family alive. The lack of visibility plagues women directors, actresses, and producers, and Bigelow’s film itself does nothing but support that invisibility. In order to understand the performance of the female gender and motherhood, there must be attention towards independent film and start awarding those films that present visible, complex female characters.

Image Reference

References

Berns, Fernando Gabriel Pagnoni. 2016. Motherhood and Identity in Contemporary Argentine Cinema. In Screening Motherhood in Contemporary World Cinema, edited by Asma Sayed. Demeter Press.

Bigelow, Katheryn, director. 2008. The Hurt Locker. Voltage Pictures.

Diéguez, Danae C., and Odile Bouchet. 2012. “¿Ellas Miran Diferente? Temas y representaciones de las realizadoras jóvenes en Cuba / Ont-Elles Un Regard Différent ? Thèmes et représentations des jeunes réalisatrices à Cuba.” Cinémas D'Amérique Latine, no. 20, 150–162. https://doi.org/10.4000/cinelatino.617

Holson, Lauren. 2019. “Latinos Are Underrepresented in Hollywood, Study Finds.” The New York Times. August 26, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/08/26/movies/latinos-hollywood-underrepresented.html

Johnson, J. Lauren. 2014. “Our Films, Our Selves: Performing Unplanned Motherhood through Videographic Inquiry.” Performing Motherhood: Artistic, Activist, and Everyday Enactments, edited by Amber E. Kinser et al. Demeter Press. JSTOR. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1rrd9tv

Katz, Ana, Director. 2015. Mi Amiga del Parque. Visit Films.

OʹReilly, Andrea. 2016. Matricentric Feminism: Theory, Activism, Practice. Demeter Press. JSTOR. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1rrd8b4

Pancrazi, Jean-Noël, director. 2015. Dólares de Arena. Breaking Glass Pictures.

Peberdy, Donna. 2011. Masculinity and Film Performance:Male Angst in Contemporary American Cinema. Palgrave Macmillan Limited. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230308701

Ramos Hernández, Patricia, Director. 2016. El Techo. JNV Productions.

Rondón, Mariana, Director. 2013. Pelo Malo. Pragda.

Smith, Stacy L, Marc Choueiti, Ariana Case, Dr. Katherine Pieper, Hannah Clark, Karla Hernandez & Jacqueline Martinez. 2019. "Latinos in Film: Erasure on Screen & Behind the Camera." USC Annenburg Inclusion Initiative. http://assets.uscannenberg.org/docs/aii-study-latinos-in-film-2019.pdf

[1] Holson, Lauren. 2019. “Latinos Are Underrepresented in Hollywood, Study Finds.” The New York Times. August 26, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/08/26/movies/latinos-hollywood-underrepresented.html

[2] Smith, Stacy L, Marc Choueiti, Ariana Case, Dr. Katherine Pieper, Hannah Clark, Karla Hernandez & Jacqueline Martinez. 2019. "Latinos in Film: Erasure on Screen & Behind the Camera." USC Annenburg Inclusion Initiative. http://assets.uscannenberg.org/docs/aii-study-latinos-in-film-2019.pdf, 3.

[3] Peberdy, Donna. 2011. Masculinity and Film Performance:Male Angst in Contemporary American Cinema. Palgrave Macmillan Limited. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230308701, 29.

[4] Johnson, J. Lauren. 2014. “Our Films, Our Selves: Performing Unplanned Motherhood through Videographic Inquiry.” Performing Motherhood: Artistic, Activist, and Everyday Enactments, edited by Amber E. Kinser et al. Demeter Press. JSTOR. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1rrd9tv, 292-293

[5] OʹReilly, Andrea. 2016. Matricentric Feminism: Theory, Activism, Practice. Demeter Press. JSTOR. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1rrd8b4, 12.

[6] OʹReilly 14.

[7] OʹReilly 13-14

[8] Berns, Fernando Gabriel Pagnoni. 2016. Motherhood and Identity in Contemporary Argentine Cinema. In Screening Motherhood in Contemporary World Cinema, edited by Asma Sayed. Demeter Press, 291

[9] trans. double labor workday

[10] Diéguez, Danae C., and Odile Bouchet. 2012. “¿Ellas Miran Diferente? Temas y representaciones de las realizadoras jóvenes en Cuba / Ont-Elles Un Regard Différent ? Thèmes et représentations des jeunes réalisatrices à Cuba.” Cinémas D'Amérique Latine, no. 20, 150–162. https://doi.org/10.4000/cinelatino.617, 152.

[11] Katz, Ana, Director. 2015. Mi Amiga del Parque. Visit Films, 7:25-7:41.

[12] OʹReilly 14

[13] Katz 9:37-9:53.

[14] Rondón, Mariana, Director. 2013. Pelo Malo. Pragda. 51:29