Saturday Night Lear: "SNL” Cast as Today's Shakespearian Fools

By Jack Wolfram

Emory University

Recently finishing its forty-fifth season, NBC’s live television variety show Saturday Night Live (SNL) has developed a reputation for disregarding the comedic boundary “lines” that are rarely crossed when discussing certain issues concerning the sociopolitical world, current events, and pop culture. Over the past several years, SNL casts predominately focus the majority of their satirical skits and sketches on the inherent character of powerful, high-profile entities. Due to the live broadcast nature of the show, SNL actors are notorious for taking full advantage of this unique comedic platform where very little dialogue is censored. These comics’ performances every Saturday night resonate far beyond the simple guffaws of entertainment. Their portrayal and parody of current events and political issues evoke darker and deeper truths about the roots of these conflicts. SNL is not just about jokes. It is about illumination.

In the same vein, William Shakespeare’s play, King Lear, contains a character whose demeanor and actions parallel those of Saturday Night Live’s comedians and entertainers. Lear’s Fool says whatever and does whatever he wants without any regard for society’s social protocols. Court fools in Shakespeare’s era possessed a degree of protective immunity, so as to entertain without fear of punishment.[1] Although those around him in the play treat him merely as entertainment, the Fool continually sheds light on the grave realities and unintended consequences of others’ actions throughout King Lear. He, too, offers illumination through what his audience perceives to be humor and nonsense.

In a time in which William Shakespeare’s work still remains astonishingly relevant to current events and our day-to-day lives, I became curious as to whether or not Saturday Night Live might be considered a modern-day manifestation of King Lear’s Fool. I hypothesized and eventually concluded as such because both SNL and the Fool are typically perceived as outlandish, but deliver their humor and nonsense with illuminatory, though-provoking twists. Both entities perform with no regard for social conventions or taboos, and neither fear immediate punishment for their antics. The Fool and his modern-day manifestation, Saturday Night Live, both explicitly entertain their audiences, but implicitly try to suggest and prompt change in them as well. Although multiple versions of Shakespearian texts like King Lear exist, and with them two differing versions of the Lear Fool’s character[2], I contend that the Fool in Lear is the Shakespearian ancestor of today’s Saturday Night Live, and that the latter can be strongly considered a modern-day manifestation of the former.

Similar to how we might view SNL as simply a funny late-night TV show, many characters in King Lear viewed the Fool as a mere comic. However, what Lear readers and playgoers eventually realize is that the Fool constantly attempts to illuminate much more grave, poignant realities of the situations unfolding around him. Throughout the entirety of the script, King Lear’s Fool exhibits wisdom, wit, and an uncannily clear vision of the kinds of consequences Lear’s actions in the beginning of the play will bring about. He is able to vocalize these concerns as well, as his comedic role grants him protective immunity from punishment. As Gilbert J. Rose details, many court jesters and fools in Shakespeare’s time ultimately paid with their lives for vocalizing particularly unpleasant truths or insults to their masters.[3] While King Lear does confront him after particularly pointed jabs, the Fool always manages to calm Lear down with further joke-truths and is never actively punished. For instance, in Act 1, Scene 4, the Fool’s mockery prompts Lear to deride and threaten him, but the king begins to take the Fool’s jokes in stride. Lear’s Fool receives no punishments, even when threatened, which implies that the Fool has earned the right to be outspoken in Lear’s eyes. In 1.4, Lear’s reactions to the Fool begin at an angry, threatening level, but then gradually tone down:

Lear: Take heed, sirrah-the whip. […]

A pestilent gall to me. […]

Why, no, boy ... […]

A bitter fool! […]

No, lad; teach me. […]

Dost thou call me fool, boy?

Fool: All thy other titles thou have given away ...[4]

In this scene, King Lear’s child Goneril enters after the Fool grounds Lear with a string of comedically-worded truths; Lear has indeed given away his kingdom, leaving himself effectively title-less, and the latent truth in the Fool’s jab accordingly affects him. We see the impact of this realization upon Goneril’s reentry, the manipulative daughter entering to meet “a changed Lear, addressing her with cool and critical authority”.[5] Although this change in and of itself bore relatively minor consequences within the grand scheme of King Lear, the Fool’s actions prompting it give rise to a central question regarding the Fool’s character: is he just “fooling” around, or is he truly attempting to sway Lear from his misled, erroneous course of hubristic kingdom-breaking? In the words of Hilary Gatti, “We may ask if his [Lear’s] Fool, once he has finally appeared on the stage in Act 1, scene 4, follows a strategy directed towards a particular aim. Does he pursue an end which will change the course of events as he finds them when he makes his first appearance in the world of Shakespeare’s play?”[6] I contend that he does.

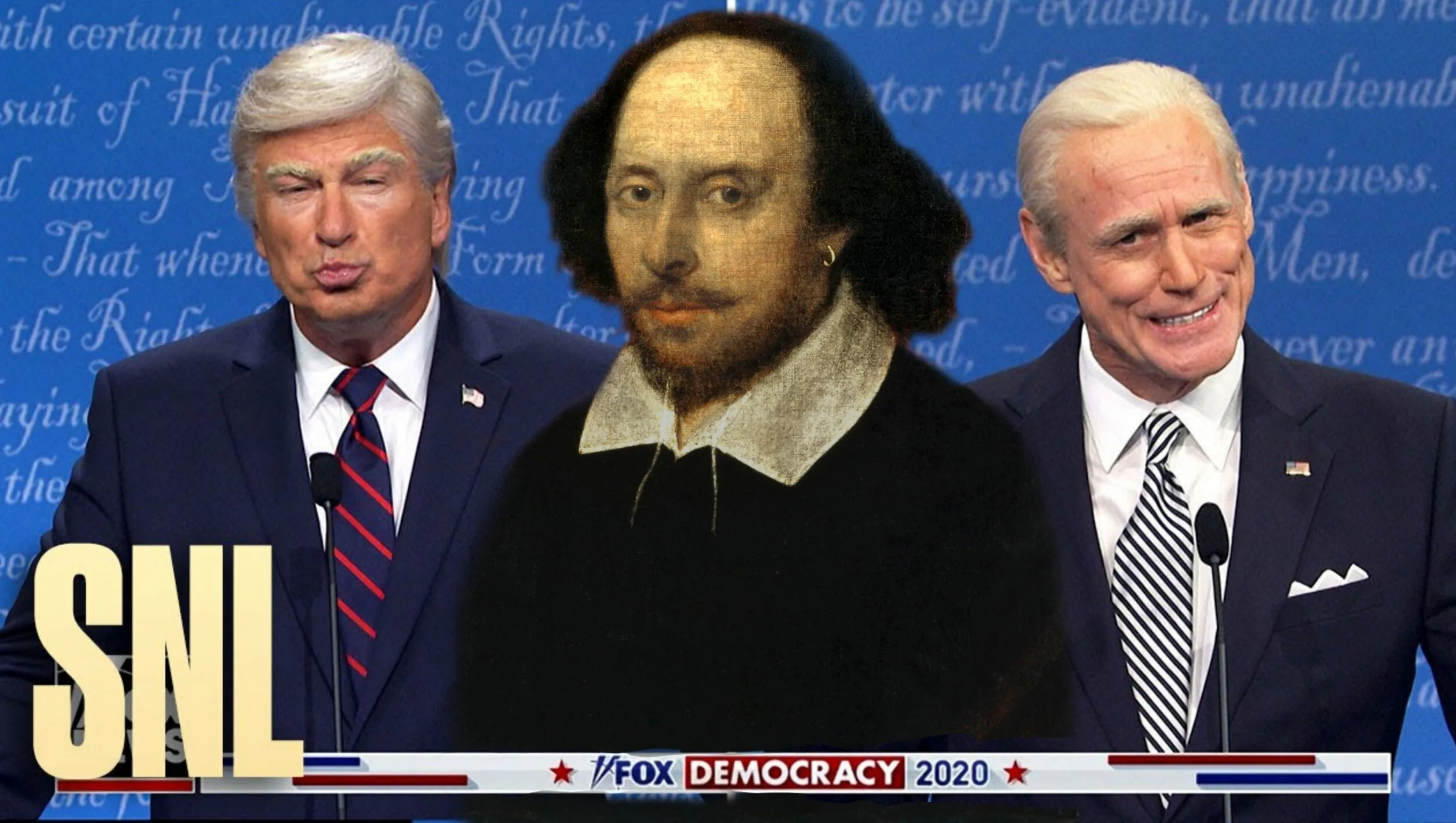

The Fool does not mock the foolish ways of others simply for the sake of mockery. Using the most effective tools he has at his disposal—comedic talents, wordplay proficiency, and his close relationship with the King—the Fool attempts to illustrate the erroneous nature of authority figures’ ways for all of those he entertains in doing so, including the authority figures themselves. SNL performs similarly with its own audiences via parody, spoof sketches, and character portrayals. Consider Saturday Night Live’s sketch about the first debate of the United States’ 2020[s6] presidential election cycle, for instance. The debate itself was hosted by Chris Wallace on Tuesday, September 29th, 2020, with Democratic nominee Joe Biden and sitting President Donald Trump; news broke later that week that Trump had contracted COVID-19 and infected many high-profile Republican peers amid his vehement rebukes of mask wearing, social distancing, and other preventative safety measures.[7][s7] [WJ8] In their Saturday spoof of this debate, the entertainers of NBC’s Studio 8H called attention to the President’s carelessness about COVID-19 amidst a larger critique of the chaos he sowed via interruptions throughout the event:

Wallace: Each candidate will have two minutes uninterrupted–

Trump: Boring!

Wallace: Mr. President, I haven’t even introduced the candidates yet.

Trump: Tell that to my Adderall, Chris. Now, let’s get this show on the

road and off the rails.

Wallace: And you did take the COVID test, you promised to take in

advance, correct?

Trump: Uh, absolutely. [Holds up crossed fingers] Scout’s honor.

Wallace: President Trump has already introduced himself. So, let’s now

welcome the democratic candidate–

Trump: Boo. Here comes the booing.

Wallace: Former vice-president of the United States–

Trump: Allegedly.

Wallace: And senator from Delaware–

Trump: Not even a real state.

Wallace: Joe Biden.[8]

Wallace (Beck Bennett) and Trump’s (Alec Baldwin) back-and-forth in these opening lines highlights what made the debate, as SNL put it, “pretty fun to watch as long as you don’t live in America,” The utter lack of professionalism on our sitting president’s part and his later-exposed abject carelessness for the health and safety of those around him, including Biden and Wallace, portrayed the egotistical nature of our nation’s leader. Within the very first minute of the sketch, SNL’s Bennett and Baldwin already offer a critique of authority embedded [s9] in their satirical scene-play.

As modern-day manifestations of Shakespeare’s Fool from King Lear, SNL comedians use their extraordinary wits, creativity, quick-thinking minds, and physical abilities to highlight the utter ridiculousness of various modern issues, political figures and current events through humor. One such instance of this comedic politicking is a “Weekend Update” segment airing prior to Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg’s Congressional testimony in 2018.[9] Reoccurring segment hosts Michael Che and Colin Jost, portraying themselves, interview “Mark Zuckerberg” – played by Alex Moffat about Facebook’s then-alleged mishandling of users’ data. Che and Jost pose reasonable questions to their in-character castmate about Facebook’s planned recompenses to the millions of users whose information the company holds in its databases; though, only to be met with exaggerated versions of the real-life Facebook CEO’s seeming indifference about righting these wrongs. Jost recognizes that “a lot of people now are calling on you to resign from Facebook,” to which Zuckerberg retorts, “No way, homie. Because according to our datasets, I don’t have to, and you can’t make me.” When Zuckerberg asserts that “Facebook is going to change,” Jost asks if users will now be able to delete personal data from the site; Zuckerberg laughs in his face. [10] “No backsies.” Within the framing device of an interview, Jost and Moffat hit on a harrowing truth at the root of the latter’s laughably forward character portrayal – corporate commodification of our online lives often goes relatively unpunished, despite perpetrators’ performative apologies. The Saturday Night Live team’s comedic talents pad serious commentaries that are hardly humorous in and of themselves.

Humor serves as the primary means by which the Fool communicates with the King about serious subject matters as well. In Act 1, upon hearing King Lear propose his self-absorbed, inheritance divvying contest of affection, the Fool offers the King his coxcomb (the traditional hat of a court fool or jester). In doing so, the Fool implies that Lear behaves foolishly enough to become a fool himself. Later in the scene, further criticizing Lear’s foolish decisions, the Fool exclaims:

To give away thy land,

Come place him here by me

Do thou for him stand.

The sweet and bitter fool

will presently appear.[11]

If any other character were to call King Lear out in such a manner, his response would have been much more severe. For instance, the King exiles Kent, a servant, and gives him a death threat simply for interrupting him.[12] However, because the Fool earned the right to be outspoken through his humor[s10] , Lear only mildly contests these criticisms. [s11] Comedy becomes the Fool’s vehicle for openly checking a powerful leader’s decisions – a line few are often allowed to cross. The Fool’s crossing of that proverbial line in order to capture his audience’s attention is another element of his character paralleling Saturday Night Live. The show’s weekend entertainers effectively dodge punishment for their portrayals and critiques of various high-profile figures due to their platform’s storied reputation. For instance, Trump and his political posse have lambasted actor Alec Baldwin for Baldwin’s portrayal of him frequently over the past four years, but Baldwin regularly portrays the controversial business-mogul-turned-president in nationally televised SNL skits regardless (an example being the afore-described first presidential debate).[13] Those who bear the brunt of SNL’s jokes have little say in whether or not their comics can make such jokes – just like the Fool, the reputation that Saturday Night Live has developed largely frees its casts from outside censorship[s12] . The most that those they lampoon can do in response is articulate their feelings, as Lear occasionally does with the Fool, too.[14]

Whereas parody, spoof sketches, and character portrayals are Saturday Night Live’s primary comedic methods of highlighting dark realities within our contemporary context, the Shakespearian Fool’s strategy in King Lear revolves around employing “linguistic paradox and wordplay” to a similar end.[15] Role reversal is a significant component of the Fool’s methodology; he continually tries to place himself in the role as master to the King and in turn focuses on King Lear’s abject foolishness. For instance, the Fool calls Lear “my boy” several times in the latter half of King Lear’s script, which registers as ironic with us as an audience because Lear was calling the Fool that very same thing during an earlier portion of the play.[16] This king-as-fool-and-fool-as-king dynamic can be observed in numerous different ways throughout King Lear, starting from the Fool’s very first scene: as described earlier, the Fool presents Lear with his coxcomb hat, as if Lear was meant to put it on and take on the Fool’s role as well. Later in the play, as Lear further descends into madness, the Fool tries to convince his master to swallow his pride, seek forgiveness from his daughters, and get out of the rain:

“O nuncle, court holy water in a dry house is / better than this rainwater out o' door. Good nun- / cle, in, and ask thy daughters blessing. Here’s a night / pities neither wise men nor fools.”[17] However, Lear ignores him, instead cursing his daughters as he and his Fool stand outside in the middle of a torrential downpour.

The Fool’s interactions with Lear demonstrate that the former is definitely invested in the well-being of the latter and spends the majority of the play attempting to make Lear recognize the error of his ways and act to correct such follies. Although the Fool eventually succeeds in pushing Lear to realize his mistake in surrendering all of his power on the basis of false displays of affection by Goneril and Regan, the latter half of the Fool’s mission – spurring Lear to reunite his fractured kingdom and family – proves unachievable, as Lear renders himself both powerless and mad by the end of the play. Thus, while the Fool proved himself entertaining and eye-opening, his “performances” (per se) failed to directly alter the course of the plot. This draws a parallel to today’s Saturday Night Live performances because though certain skits may highlight issues that viewers otherwise might not have been considering, the show has often failed as a call to action. Think back to the 2016 election, for instance, during which SNL threw considerable support behind Hilary Clinton to no avail.[18] Ultimately, their respective audiences keep watching the Fool and Saturday Night Live out of a desire for entertainment, not necessarily for socio-political motivation.

I contend that Saturday Night Live embodies the continuation of Shakespeare’s King Lear Fool into our modern world. However, one must also consider the possibility that this was not the Fool whom William Shakespeare created for King Lear. There are two widely accepted versions of King Lear: one published in 1623 as part of Shakespeare’s famous First Folio, and a Quarto version published in 1608. The character of the Fool differs significantly between the Quarto and Folio editions of the play, and scholars have debated for years as to which version should reign supreme. In “The Fool in Quarto and Folio King Lear,” Oglethorpe University professor and Folger Shakespeare Scholar Robert B. Hornback explains the debate:

As a number of Renaissance textual scholars argued persuasively in the 1980s, notably in The Division of the Kingdoms, the Quarto and Folio versions of King Lear are distinct texts often producing different literary and theatrical effects. Unfortunately, interest in such variation was inadvertently quelled by the vast majority of “revisionist” critics who argued that the Folio text was simply an improved version of the earlier Quarto text. As a result, much of their work focused on zealously “proving” that the Folio renderings of characters were superior to their supposedly deficient counterparts in the Quarto. Ultimately, a sensible majority of critics were persuaded by arguments that the two texts were substantially different but nonetheless pointed out the flawed, subjective, and ultimately unprovable logic of authorial perfection as the sole motivation for substantive textual variants.[19]

The book Hornback referenced, The Division of the Kingdoms, further explains that the differences between the Folio Fool and the Quarto Fool largely stem from a 54-line rewrite of the Fool’s part (which is only about 225 lines long to begin with) which “significantly alters the Fool’s personality and quite changes the direction of his dramatic development.”[20]

It seems that the role of the Fool in the original 1608 Quarto edition of King Lear was written by Shakespeare for the renown Shakespearean actor Robert Armin, “the self-proclaimed ‘Clown of the Globe’,” who played a very specific variety of fool. [21] Armin essentially defined the early-17th-century trend of playwrights substituting fools such as Touchstone, Feste, Lavatch, and Carlo Buffone for the ridiculous, slapstick clowns of the 1580s and 1590s; from 1600 until Armin’s retirement in 1613, “artificial” fools ruled the comedic world of theater. Thus, Shakespeare may have written his Quarto King Lear Fool so as to capitalize on having London’s most popular “artificial fool” in his acting troupe;[22] the Quarto Fool reads as a wiser, funnier, and more bitter character than the later Folio version as a result.

Shakespeare’s 1623 First Folio presents a version of King Lear containing a sweet, natural Fool completely unlike the Quarto character of the same name. Viewed in context, this change is perfectly reasonable. Robert Armin, the clown for whom Shakespeare wrote the role of the Fool in Lear, retired in 1613. That year, in which it is also recorded that directors struggled to find suitable actors for the fool role in King Henry VIII, denotes the earliest reasonable date for King Lear’s revision. As Shakespeare retired by the end of 1613 (Hornback 313) and died in 1616, it is possible that William Shakespeare did not pen the Folio revision himself. This therefore may point towards the Quarto version as “Shakespeare’s” King Lear, and the Quarto Fool as “Shakespeare’s Fool.”

Several “Fool” characters from other Shakespearian plays reaffirm this characterization of the Fool in Lear and serve to further illustrate the ancestral line between Shakespearian fools and those of Saturday Night Live today. Touchstone, from As You Like It, is a quick-witted royal jester as well, and a likewise “astute observer of human nature” in his commentaries throughout the play.[23] Much like Lear’s Fool, Touchstone exhibits notable linguistic savvy and is a frequent argument-twister. Twelfth Night’s Feste, another clown of the crown, showcases the same brand of extraordinary language command in his quips and observations as well. Furthermore, Feste is both a commentator and a directly involved character in the play, too, paralleling Lear’s Fool even further. Given the striking similarities between these three Shakespearian “Fool” characters, it seems reasonable to assert the (Quarto) Lear Fool’s legitimacy as both the accepted version of his character and a predecessor to the public “court fools” of today.

Nearly five hundred years after his death, William Shakespeare’s works still live on and remain relevant in our world today. One such exhibition of his literary legacy is Saturday Night Live, which can be viewed as a modern-day manifestation of “The Fool” from King Lear: an intelligent character who jabs and teases the powerful without fear of punishment, explicitly entertains his audiences, but implicitly tries to suggest and prompt ideological change in their perspectives on authority figures and structures as well. Although multiple versions of King Lear exist, and with them two differing versions of the Fool’s character, I contend that the Fool is the Shakespearian ancestor of today’s Saturday Night Live, and the latter can be strongly considered a modern-day manifestation of the former (and many of its Shakespearian clown-character colleagues). On a certain level, this lineage implies that anti-authoritarian, message-charged entertainment is hardly a twenty-first-century phenomenon, as many today who denounce it mistakenly assert. While Shakespeare himself is dead, his plays, his characters, and his fools’ nuanced brand(s) of illuminatory entertainment are still very much alive; in fact, you can find traces of each just about every Saturday night on NBC.

References

[1] Gilbert J. Rose, “King Lear and The Use of Humor in Treatment,” in Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association (New York: American Psychoanalytic Association, 1969), 928.

[2] As depicted in one of the more commonly-accepted versions of King Lear, the Folger Shakespeare Library edition (which consists of the Quarto version with Folio variations interwoven into the text).

[3] Rose, 927.

[4] William Shakespeare, The Tragedy of King Lear, ed. Barbara A. Mowat and Paul Werstine (New York: Washington Square Press, 2000-2009), 1.4.113, 117, 119, 135, 139, 142, 151-53.

[5] Rose, 930.

[6] Hilary Gatti, “Nonsense and Liberty: The Language Games of The Fool in Shakespeare’s King Lear” in Nonsense and Other Senses: Regulated Absurdity in Literature, ed. Elisabetta Tarantino and Carlo Caruso (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2009), 150.

[7] Olivia Nuzzi and Ben Jacobs, “The White House Is Spreading Virus and Lies,” Intelligencer (New York Magazine, October 4, 2020), nymag.com/intelligencer/2020/10/white-house-spreads-covid-19-and-lies-about-trumps-health.html.

[8] Don Roy King, transcriber. “First Debate Cold Open - Transcript.” SNL Transcripts Tonight, October 15, 2020. https://snltranscripts.jt.org/2020/first-debate-cold-open.phtml.

[9] “Weekend Update: Mark Zuckerberg on Cambridge Analytica.” Saturday Night Live, season 43, episode 17, featuring Colin Jost, Michael Che, and Alex Moffat, aired April 7, 2018, in broadcast syndication. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GqRo9xYKnfA.

[10] “Weekend Update: Mark Zuckerberg on Cambridge Analytica.”

[11] Shakespeare, (1.4.145-49)

[12] Shakespeare, 1.1.174, 179.

[13] Associated Press. “Donald Trump, Alec Baldwin Renew Twitter Feud.” Billboard, March 5, 2018. https://www.billboard.com/articles/news/8227763/president-donald-trump-alec-baldwin-renew-twitter-feud-snl-saturday-night-live.

[14] Genevieve Carlton. “Political Figures Share What They Really Thought Of SNL's Impressions Of Them.” Ranker, June 21, 2019. https://www.ranker.com/list/how-political-figures-feel-about-snl-impressions/genevieve-carlton.

[15] Gatti, 151.

[16] Shakespeare, 1.5.17, 49

[17] Shakespeare, 3.2.12-15.

[18] Hillary Busis. “This Is How Saturday Night Live Mourned Hillary Clinton's Loss.” Vanity Fair, November 13, 2016. https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2016/11/snl-hillary-clinton-hallelujah-kate-mckinnon.

[19] Robert Hornback, “The Fool in Quarto and Folio King Lear” in English Literacy Renaissance (Brookhaven, GA: Oglethorpe University, 2004), 306.

[20] John Kerrigan, “Revision, Adaptation, and the Fool in King Lear” in The Division of Kingdoms: Shakespeare’s Two Versions of King Lear, ed. Gary Taylor and Michael Warren (Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press, 1983), 218.

[21] Hornback, 350.

[22] Robert Bell, “Motley to the View: The Shakespearian Performance of Folly” in Southwest Review (Dallas: Southern Methodist University, 2010), 60.

[23] “The Ultimate Guide To Shakespeare's Fools.” No Sweat Shakespeare. No Sweat Digital, March 22, 2020. https://www.nosweatshakespeare.com/blog/ultimate-guide-shakespeares-fools/.