Fate in a Fatalistic World

by Emily Ward, University of Notre Dame

Yvanox. The Theatre of Dionysus Eleuthereus in Athens. Athens, Greece, https://pixabay.com/photos/greek-theatre-greece-antique-2144095/

Are freedom and fate mutually exclusive concepts? Can we accept our own insignificance without devolving into personal existentialism? What is the value in making a choice if we are condemned to a predetermined destiny? These are the questions Sophocles attempts to answer through his works Oedipus Rex and Antigone. Athenian society, which these plays are referencing and interpreting, heavily centered around the conception of democracy. Unique at the time, Athenian democracy granted individuals power in an otherwise deterministic world. Sophocles's friend Pericles, the famous orator, said of Athens, "each single one of our citizens, in all the manifold aspects of his life, is able to show himself the rightful lord and owner of his own person." [1] In the context of Athenian political life, free-will was necessary to maintain the entire concept of their democracy, to believe that each choice the demos, or the populace of Athens, makes matters.

In direct contrast to this political system, the religion of Athens was highly deterministic, relying on prophetic mechanisms such as oracles and divination to determine external circumstances. According to Adkins, portents were a common aspect of ancient Greek society to divine the will of the gods. [2] This divination is the practice that Tiresias participates in throughout the Oedipus corpus. The gods could act indiscriminately, and the men had no power over them. This imbalance served to explain tragedies that are exempt from human influence. The actions of angry and temperamental gods, whom the Athenians had no control over, could explain plagues, floods, famine, and earthquakes.

Greek tragedy as a genre derives immense meaning from the distinction between gods and men. The prescribed order of the world was called cosmos, and it delineated completely distinct aspects of society. Moreover, these tragedies were written as entries into a competition, thus relying on an aspect of relatability within the characters and themes of the plays. Therefore, Sophocles first wrote the Oedipus Rex trilogy in fifth-century Athens with the full understanding that the audience would relate dilemmas presented within his work to potentially problematic aspects of their contemporary society. With this social awareness in mind, Sophocles creates conflicting depictions of fate within the Oedipus tragedy, specifically by illustrating Antigone as an individual agent and Oedipus as a victim of destiny. How does Sophocles rationalize these contradictory presentations, and what might they imply for Athenian society in a broader sense? Throughout this paper, I will utilize the terminology of "determinism" and "predestination" interchangeably as descriptors for fatalistic philosophy that disregards free will, particularly in reference to Athenian religion. In Oedipus Rex and Antigone, Sophocles reconciles the personal autonomy of democracy with the determinism of divination through clear distinction of ideological domain.

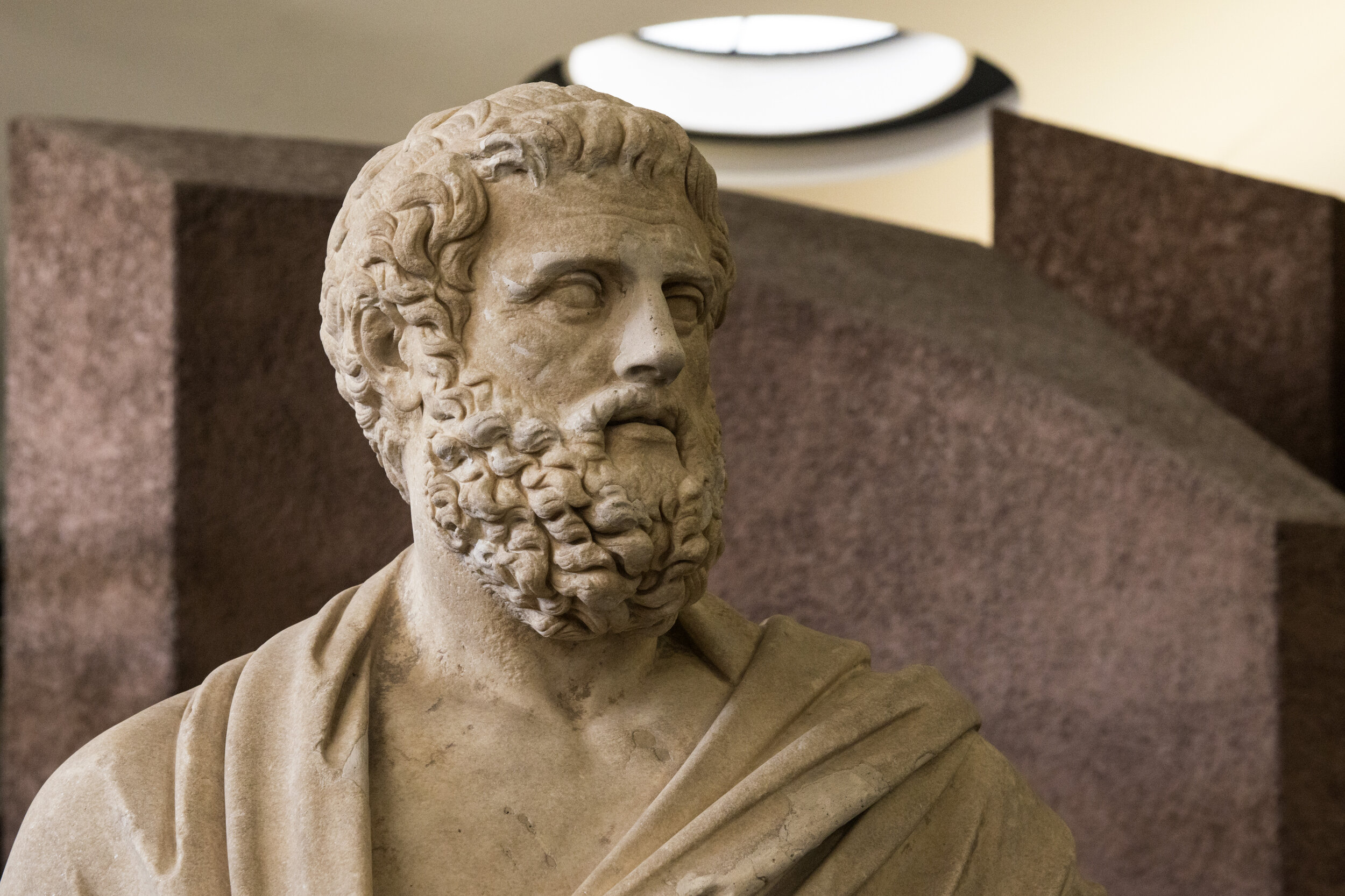

Sano, Egisto. The Lateran Sophocles - II. 2014. Museo Gregoriano Profano. Città del Vaticano, https://flic.kr/p/md1ppB.

I. The Cruel Impartiality of Fate

In Sophocles's Oedipus, the titular character, Oedipus, discovers his pre-existing tragic fate: one that ends with his wife and mother's death and his own blinding and exile. The progression of his character throughout the play, in combination with other literary aspects, illustrates an intensely fatalistic representation of destiny, specifically as it applies to a seemingly powerful and upstanding individual.

When Oedipus is first introduced, he is a character with agency, so much so that his subjects call to him for aid against the indomitable tragedies that befall them. Oedipus had already saved the people of Thebes from the Sphinx, which is why he was granted dominion over the city. The Thebans also call upon him to save them from the plagues that currently wrack the population. Oedipus is glorified as a man more powerful than all others, with supplicants saying, "You cannot equal the gods… But we do rate you first of men, both in the common crises of our lives and face-to-face encounters with the gods." [3] This quote is of particular interest because it places Oedipus in a position of authority within the given crisis, and yet these petitioners specifically designate Oedipus as below the gods. Even prior to the discovery of his prophecy, Oedipus is implied to be powerless against the will of the gods.

This vulnerability becomes more prominent as the story progresses, and Oedipus uncovers more about the truth of his life and the destiny he has already partially fulfilled. This discovery is partly due to the words of the prophet Tiresias, who makes an appearance in Antigone as well. Tiresias proclaims Oedipus as a perpetrator of patricide and incest, stating, "Revealed at last, brother and father both to the children he embraces, to his mother, son and husband both - he sowed the loins his father sowed, he spilled his father's blood!" [4] This certainty, since it comes from the soothsayer who initially proclaimed Oedipus's destiny, implies a distinct inevitability in such destiny. This prophecy refers to Oedipus’s unwitting murder of his father Laius at crossroads, where Laius — the king of Thebes at the time — offended Oedipus and refused to move. Obviously, Tiresias is correct in his predictions; Oedipus' crimes are revealed. Later in the play, this tragedy surrounding the king goes even further back in his life, with the shepherd who rescued him as a child saying, "you were born for pain." [5] There was not a moment in Oedipus' life where he was free of his fate; from birth, he had been destined for this tragedy and punishment.

Moreover, the Olympian gods' role in this play presents an evident lack of Oedipus’s personal autonomy. First, the chorus explicitly illustrates the powerlessness of men in the face of the Olympians: "Destiny guide me always, Destiny find me filled with reverence pure in word and deed. Great laws tower above us, reared on high born for the brilliant vault of heaven." [6] The Olympians are not limited in the same ways as men, and their will is law, even if that will goes against mortal notions of justice, as it happens with Oedipus. This hero is morally innocent but suffers, just as life has certain tragedies that are exempt from human influence. Apollo hails plagues and natural disasters upon the city of Thebes, causing the innocent people of the city to suffer without cause or method of redress. [7] This intense focus on the weakness of men compared to the power of the gods indicates the play’s setting in the divine cosmos. The text operates within the societal rules and understandings of that context in particular, which further exemplifies how beholden Oedipus’s destiny is to external forces.

Certain scholars have attempted to disagree with the previous argument by arguing that Oedipus is still an actor with free-will; they prescribe ancient understandings of justice to his choices at the crossroads. One such scholar is R. Drew Griffith, who states that Oedipus is not morally innocent, specifically arguing that predestination does not constitute a compulsion. Thus, Oedipus committed patricide of his own free-will. However, this notion only functions when we analyze the play through a lens of justice that does not apply the concept of fate. [8] This argument holds Oedipus morally responsible, but the death of Laius at the hands of Oedipus in any circumstances would constitute a tragedy. As Griffith states, “Oedipus’ fate does not absolve him of blame, since he could have fulfilled it in total innocence.” [9] While Griffith uses this example to indicate Oedipus’s own culpability in the face of unconditional fate, this idea also illustrates a deeper truth: tragedy was destined to befall Oedipus, even if he made this specific choice of 'free-will' in a temporal or moral sense. The possibility of Oedipus remaining innocent only further underlines the lack of justice in external forces. Thus, while these are intricate and valid interpretations of the text, they do not apply in this specific analysis of Oedipus's lack of free will because there was no mechanism for him to escape the tragedy, only perhaps the moral responsibility.

II. Antigone as the Agent

In contrast to Oedipus, Antigone focuses on the political realm and, as a result, gives complete agency to its characters. This difference is most evident in the words of Tiresias, the same prophet who damned Oedipus to his tragic fate. Tiresias warns Creon after his actions in the first half of the play; Creon, the king of Thebes following the death of Oedipus, declared that the body of one of Oedipus’s sons, Polynices, would not be buried on account of crimes against the state. This declaration constituted sacrilege and was immensely dishonorable to the dead. In Antigone, Tiresias only advises Creon; he does not determine his fate, "Take these things to heart, my son, I warn you. All men make mistakes, it is only human. But once the wrong is done, a man can turn his back on folly, misfortune too, if he tries to make amends, however low he's fallen." [10] Tiresias gives Creon a way out, a way to atone for his mistake, proving that he is not doomed to the tragedy that eventually comes.

Within that same speech, Tiresias also makes an interesting claim about the mechanisms of prophecy, "The rites failed that might have blazed the future with a sign… No birds cry out an omen clear and true." [11] The typically reliable methods of prediction are failing in this specific case, thus separating the results of the play from predetermined certainties. This distinction places the blame, and the action, entirely in the hands of the key characters, not gods or prophecies. This separation is further exemplified by the lack of godly action in the play. Whereas in Oedipus, Apollo's plague was the catalyst for the entire act, the actions and will of men and women entirely determine Antigone's plot.

The character Antigone also clearly acts with agency, openly taking full responsibility for her choices: refusing to obey the orders of the king and refusing to remain silent about this action. This freedom is exemplified in her words to Creon after she buried her brother against the king's edict, "Die I must, I've known it all my life… And if I am to die before my time I consider that a gain." [12] This statement is particularly fascinating as it deals with an immutable facet of human life, death, yet it applies a tremendous amount of personal choice.

Scholar Sarah Iles Johnston further highlights Antigone’s agency in death by arguing that her entombment mirrors other ancient depictions of the sacrifice of virgins, yet with the critical distinction that Antigone hangs herself. In doing so, she does not allow herself to be killed for the crime, choosing her method and time of death instead. This agency, in the face of inescapable mortality, powerfully underlines the importance of individual choice throughout the play.

Johnston also argues that this individuality corresponds with a revolutionary implication. In her analysis, she equates the sacrifice of virgins with the sacrifice of potential children and families that might serve the state, which is why they have power. In keeping with this belief, Antigone's suicide allows her to strip the power that the state has over her and her body. [13] Antigone's death also differs from these sacrificial murders through the mechanisms of law in place of religion. The Thebans do not kill her to appease some god, but to appease their king Creon. These implications support the play's occupation of the democratic, rather than religious, cosmos.

To conclude, Sophocles’ Antigone highlights the human agency of the central characters, Creon and Antigone. Their actions are the driving force behind the whole narrative. The only inevitability of tragedy in Antigone comes from the natures of the characters themselves, from the stubbornness of their actions, but no external force decides for them.

Harrsch, Mary. Oedipus at Colonus by Jean-Antoine-Theodore Giroust 1788 French Oil (5). 2006. Dallas Museum of Art. Dallas, Texas, https://flic.kr/p/rY5MX

III. Conclusion

Oedipus suffers at the hands of an immutable fate, a predetermined destiny of tragedy. Despite his immense heroism and strength, he is powerless against the gods and divine external forces. Antigone and Creon suffer by their own hand; their choices lead to their demise. Though both of these plays are steeped in tragedy, the misfortune is derived from opposite sources. Oedipus is about the divine and the religious. Antigone is about the earthly and the democratic. By having these two plays exist in the same trilogy, Sophocles rationalizes seemingly opposing ideologies of free-will and determinism. He states that so long as the divine and the democratic are clearly delineated, free-will and predestination can coexist.

Thus, in combining these two aspects of society, Athenians operated with a sense of personal, political autonomy while simultaneously being victims of indiscriminate fate. Sophocles recognized this apparent contradiction and attempted to represent and simultaneously reconcile it through depictions in Oedipus and Antigone. He did so by dividing the two plays into separate cosmos. Oedipus is part of the divine cosmos, Antigone is part of the democratic one. As a result, Oedipus's 'choices' lead him to an inevitable destiny, while Antigone's choices are impactful and actionable, just as they must be to serve in a democracy.

Antigone is limited to the actions of men, as seen in the conflict. The protagonist disagrees with Creon, who then kills her. There is no godly or external influence involved. This independence mirrors the conception of democracy, that these are the choices of men, and those choices will impact men. Oedipus is a conflict between man and the gods or destiny, and the main character Oedipus is powerless against them. The play is set after he has killed his father and married his mother, which further emphasizes the inevitable nature of Oedipus’s two crimes.

Overall, these two seemingly contradictory depictions of fate are actually complementary, as they allow Athenians to rationalize unavoidable tragedy that seemingly happens to good people, with a belief in an impactful autonomy of men. It also allows the Athenians to avoid any culpability when things go wrong, blaming such a result on the gods or destiny, while at the same time they could laud themselves when things go well, claiming credit.

What purpose does this reconciliation by Sophocles between the democratic system and religion serve in modernity? Although these plays are over two thousand years old, the progression of time has not led to a greater understanding of the human place in the world. Democracy has become far more commonplace, and the ever-popular liberalist philosophies have guaranteed individual freedoms, but even in modern Christian society, there is a common discomfort with the religious concept of an omnipotent God. Countless philosophers and theologians have attempted to reconcile free-will with and an omnipotent God, just as Sophocles did.

Moreover, we still feel just as helpless as the ancient Athenians in the face of tragedies and just as angry or disillusioned when they befall innocent people. Humans are naturally empathetic, and the knowledge that the world is not inherently moral is often hard to digest. The works of Sophocles remind us that we cannot be gods, invincible to the indomitable whims of the universe. However, we can find comfort in the fact that over two thousand years, we have retained that empathy and that desire to make the world less tragic than it appears. We strive to create pockets of civilization, places where our thoughts and our choices matter, even if it means suffering for them.

Notes

[1] Thucydides, The History of the Peloponnesian War. Trans. by Rex Warner. (New York, NY: Penguin Books, 1972), 147.

[2] Lesley and Roy A. Adkins, The Handbook to Life in Ancient Greece. (New York: Facts On File, 2005), 373-375.

[3] Sophocles. “Oedipus the King.” In The Three Theban Plays. ed. and trans. Robert Fagles. (New York: Penguin Books 1984), lines 39-43.

[4] Sophocles, “Oedipus the King,” lines 520-523.

[5] Ibid. lines 1305.

[6] Ibid, lines 954-963.

[7] Ibid, line 120.

[8] R. Drew Griffith, "Asserting Eternal Providence: Theodicy in Sophocles' 'Oedipus the King,'" In Illinois Classical Studies 17, no. 2 (1992): 193-206.

[9] Griffith, “Theodicy in Sophocles,” 205.

[10] Sophocles. “Antigone.” In The Three Theban Plays, ed. and trans. Robert Fagles. (New York: Penguin Books, 1984), lines 1131-1135

[11] Sophocles, “Antigone,” lines 1120-1129

[12] Ibid, lines 512-515.

[13] Sarah Iles Johnston, "Antigone's Other Choice" In Antigone's Answer: Essays on Death and Burial, Family and State in Classical Athens, Helios, ed. R. Lauriola and K. Demetriou (Lubbock: Texas Tech University Press, 2006). 179-184.

Bibliography

Adkins, Lesley and Roy A. Adkins. The Handbook to Life in Ancient Greece. New York: Facts On File, 2005.

Griffith, R. Drew. "Asserting Eternal Providence: Theodicy in Sophocles' 'Oedipus the King,'" In Illinois Classical Studies 17, no. 2, 1992.

Johnston, Sarah Iles. "Antigone's Other Choice" In Antigone's Answer: Essays on Death and Burial, Family and State in Classical Athens, Helios, ed. R. Lauriola and K. Demetriou Lubbock: Texas Tech University Press, 2006.

Sophocles. “Antigone.” In The Three Theban Plays, ed. and trans. Robert Fagles. New York: Penguin Books, 1984.

Sophocles. “Oedipus the King.” In The Three Theban Plays. ed. and trans. Robert Fagles. New York: Penguin Books 1984.

Thucydides. The History of the Peloponnesian War. Trans. by Rex Warner. New York, NY: Penguin Books, 1972.

About the Author

Emily Ward is a sophomore Classics and Political Science Major from Princeton, New Jersey studying at the University of Notre Dame. She is particularly interested in the intersection of classical political ideology and modern views of citizenship.