Japan's Monstrous-Feminine: Unspoken Ghost Stories

ABSTRACT

Monsters arise from the desire to disempower what is perceived as a threat. This article examines the figure of the Japanese female ghost through the theoretical framework of the monstrous-feminine, arguing that the spectacle of horror and victimhood of patriarchal narratives also contain expressions of female suffering and resistance. The article explores how, historically, the Japanese female ghost embodied the anxieties of patriarchal Japan concerning female sexuality and how contemporary artists, particularly Yuko Tatsushima, have recontextualized representations of female ghosts as figures of subversion and resistance against patriarchal norms. The article begins by exploring the traditional tales of Oiwa and Okiku, emphasizing how victimization in life under patriarchy leads to the monstrous transformation of a vengeful female subject. Through criticisms of Freudian phallocentric ideology, including Barbara Creed’s notion of femme castratice and Julia Kristeva’s idea of the abject, the essay traces how the symbolic castration enacted upon women’s bodies can be inverted into a threatening reclamation of sexual and bodily power. As examples of the monstrous-feminine, Yuko Tatsushima’s disfigured and grotesque female figures redefine and subvert traditional depictions of female ghosts.

INTRODUCTION

Debbie Felton describes the appearance of monsters as often arising “from the desire to domesticate and thus disempower what a culture finds threatening.” [1] From this notion, the “monstrous-feminine” speaks “to men’s fear of women’s destructive potential…[and] to a certain extent, fulfill[s] a male fantasy of conquering and controlling the female.” [2] Barbara Creed developed the monstrous-feminine as a framework “to analyze, challenge, confront, upend, and reinvent the cultural mythology of womanhood, femininity, and gender in relationship to monstrosity.” [3] We define the monstrous-feminine as woman-as-monster, challenging previous understandings of woman-as-victim by exploring the monstrous as ta threatening female sexuality and the subversion of patriarchal norms. In Sofia Sears and Eli Cohen’s Defining the Monstrous Feminine, traditional femininity is abandoned, and the monstrous-feminine engages in rage, desire, mortality, and violence that terrifies. [4]

In Japanese depictions of the supernatural, the imagery of the female monster is a longstanding tradition in the country’s cultural and historical media (i.e., religious texts, theater, kaidan, folktales, prints, paintings, and otherart forms). Traditionally, the female monster, by violating moral and social norms, may also reinforce expectations of the status quo precisely through their violation of norms. Natsumi Ikoma’s argues that in the figure of the Japanese female ghost - who is victimized in life and torments their perpetrators in death, patriarchal society has "transferred onto women’s body its fear of sexuality, in an attempt to control it.”[5]

The following essay analyzes and compares depictions of the “Japanese female ghost,” recontextualizing these traditional narratives through the lens of the monstrous-feminine. In particular, the essay looks at the “monstrous” in the work of the artist Yuko Tatsushima to reveal how she appropriates and subverts traditional representations of the female ghost.

OWIA AND OKIKU: A TALE OF TWO MONSTERS

Two of the most notable and widely recognizable kaiden (tales of the weird or mysterious) of Japanese female ghosts are Oiwa (Tokaido Yotsuya Kaidan) and Okiku (Banchō Sarayashiki), illustrated in Figures 1 and 2, respectively. In both stories, the titular characters experience vengeance, injustice, and suffering at the hands of male characters.

Figure 1. (left) - Portrait of Oiwa, Utagawa Kuniyoshi, 1836

Figure 2. (right) - Sarayashiki (The Plate Mansion), from the series One Hundred Ghost Stories, Katsushika Hokusai, 1831-1832

Oiwa is one of the most famous depictions of the onryo or vengeful ghost. Oiwa was the wife of the poor ronin and thief, Iemon. During their time together, Oiwa fell ill after giving birth. Iemon grew resentful and would leave Oiwa for Oume, the beautiful granddaughter of a doctor. This doctor conspired with Iemon, prescribing Oiwa a poison that would horrifically disfigure her face. Upon seeing her appearance, Iemon left her to marry Oume and asked his friend, Takuetsu, to rape Oiwa as a means for a legitimate divorce by accusing Oiwa of infidelity. Unable to follow through, Takuetsu showed Oiwa her reflection, driving her to puncture her throat. Oiwa cursed Iemon’s name as she died, and Iemon threw her into a river. On Iemon and Oume’s wedding day, Iemon would behead Oume, thinking she was Oiwa. Oiwa’s ghost continued to torment Iemon, causing the deaths of those around him, driving him mad, and eventually to his death. Figure 1 below is one of many illustrations of Oiwa; this is Utagawa Kuniyoshi’s Portrait of Oiwa (1836), depicting her spectral form emerging from a lantern to torment Iemon. [6]

Okiku’s folktale, Banchō Sarayashiki (“The Dish Mansion at Banchō”), like Oiwa, tells of a woman who is victimized by a male character. Okiku was a dishwashing servant to Aoyama Tessen, a samurai who fell in love with her beauty. Aoyama attempted to seduce Okiku many times, but each time, she rejected him. Aoyama would grow impatient with Okiku’s rejections and attempt to blackmail her into becoming his lover. Aoyama would accuse Okiku of breaking/losing a precious heirloom, an offense punishable by death. Aoyama, in an attempt to coerce Okiku, told her he’d overlook her mistake, but only if she’d become his mistress. In the most well-known variation, after her rejection, Aoyama grows so furious that he strikes her with his sword and drops her body down a well. In Figure 2, titled Sarayashiki (1831-1832), Okiku is illustrated rising from the well, her elongated neck depicted as the heirloom plates from her story. [7]

In both folktales, Oiwa and Okiku exemplify the vengeful female ghost motif in Japanese media, where their stories center on their victimization at the hands of cruel men. Only in death do they gain power, transforming into monstrous figures that terrorize their male perpetrators.

THE FEMME CASTRATRICE

Sofia Sears and Eli Cohen state that the monstrous-feminine is a practiced performance of rage, desire, mortality, and violence. Monstrous women and female monsters represent threats to patriarchal structures and gender roles. Sears and Cohen argue that the monstrous-feminine dislodges femininity as a social construct to the point of abjection.

Julie Kristeva’s “abject” and Creed’s femme castratrice (castrating woman) are useful concepts to understand this fascination with the “female” as a monster. The abject represents the visceral human reaction to a threatened collapse of meaning.[8] Female reproductive functions (childbirth, menstruation, and decay) are abject in that they evoke fear and disgust. Creed draws upon Kristeva’s theory of abjection as a framework for the representations of the monstrous-feminine. Creed argues that all cultures and societies have a conception of the monstrous-feminine – a reimagining of the female body and her sexuality, “to be shocking, terrifying, horrific, [and] abject.”[9] The most infamous monstrous-feminine depiction that intersects Kristeva’s abject and Creed’s femme castratrice is of the Greek story of Medusa. Medusa originally was a beautiful mortal woman and priestess of the Olympian goddess Athena. Medusa’s monstrous transformation befell her after Poseidon fell in love and later violated her in Athena’s temple. Athena punishes Medusa by stripping her beauty and turning her into a Gorgon (winged creatures with serpentine hair and petrifying eyes) with the curse of turning anyone who looks upon her into stone. Medusa was later decapitated by Perseus, son of Zeus, who was sent to bring Medusa’s head as a wedding gift. Her head was later mounted to Perseus’s shield by Athena, retaining its ability to turn people to stone.

In Sigmund Freud’s interpretations in “Medusa’s Head,” to decapitate meant to castrate.[10] Freud writes, “The terror of Medusa is thus a terror of castration that…occurs when a boy, who has hitherto been unwilling to believe the threat of castration, catches sight of the female genitals, probably those of an adult, surrounded by hair, and essentially those of his mother.”[11] The decapitation of Medusa, as he claims, is derivative from the castration complex, in which the absence of the penis or phallus is cause for horror in fear of castration. The petrifying gaze of the decapitated Medusa that can turn men to stone symbolizes the horrifying first look at female genitals. Creed’s concept of the femme castratricechallenges Freud’s view that “woman terrifies because she appears to be castrated.” Instead, she argues that male fear stems from an anxiety that the woman are not castrated: “the male fears woman because woman is not mutilated like a man might be if he were castrated; woman is physically whole, intact, and in possession of all her sexual powers..”[12]

Creed argues that Freud’s usage of the Medusa being as horrifying as the sight of a mother’s genitals is not by accident, as “the concept of the monstrous-feminine, as constructed within/by a patriarchal and phallocentric ideology, is related intimately to the problem of sexual difference and castration.”[13] She challenges Freud’s passive victim role of the woman. She argues that, through their victimization, the creation of the monstrous-feminine shifts the narrative of passivity into the more active female monstrosity, the femme castratrice. The woman is a victim of cruel punishment, betrayal, and forced submission “because, by her very nature, she represents that threat of castration” through her sexuality and womanhood.[14] By transforming into the femme castratrice, through the female suffering, death, and mutilation, the castrated woman becomes the castrating woman.[15] It is this feminine monstrosity that arouses the man’s fear.

THE JAPANESE FEMALE GHOST

The monstrous-feminine transcends national and cultural boundaries as it materializes in several localized contexts revolving around shifts in a nation’s cultural landscape.[16] Female ghosts are linked to Japan’s matrilineal past, in which shamanistic practices and contact with the spirits – practices specifically conducted by female mediums and shamans – were commonplace. During the transition into the feudal period (roughly 1185-1868), Japan saw a shift from a matrilineal society to a patriarchal one, where pre-Shinto and pre-Buddhist shamanistic practices became increasingly marginalized. The proliferation of female ghosts throughout this period, according to Tanajka Takako, reveal a society in which “demonized women who engaged in non-Buddhist or non-Shinto practices and accused women of possessing wicked sexuality and a unholy nature.”[17] Notable figures from this period include the madwoman of Noh Theater, the ubume (a creature associated with the taboos of menstrual blood and pregnancy), the kosodate yurei (child-rearing ghost), the mountain-dwelling yamauba (creatures frequently accompanied by a child), and the female onryo (vengeful ghost). These examples serve to demonstrate the dangers of attachment to, and the illusory quality of, the material world. In these depictions, the female body in Japan’s cultural imagination is the most visceral embodiment of the abject.

The Japanese female ghost horrifies its audience because she is often a victim of tragedy that leads to death, is often dangerously attached, is mistreated in her life, is vengeful or sorrowful, and is frequently sexualized or defined by her sexuality.

In cases of spirits, such as Okiku (Banchō Sarayashiki), Oiwa (Yotsuya Kaidan), Lady Rokujo (Tales of Genji), and Sadako (“Ringu” 1998), all were victims of horrible deaths, later turned into ghost stories. Murder, abandonment, neglect, betrayal, suicide, and sexual abuse are often the reasons for the demise of Japanese ghosts. Their bodies in death are often marred, disfigured, and grotesque “as if to signify the pain and torture of the ‘horrible death…’”[18] Ikoma argues that the “image of female ghosts with their disfigured body and painful wounds is a symbol of fear for the horrible death, especially resulting from sexuality in male-centered Japan.”[19]

Within the monstrous-feminine, the female ghost can represent resistance in their incorporeal state. Here, the act of becoming a ghost or monster “violate[s] the rule of conduct in the patriarchal society.”[20] Ikoma states that, while women were not to display any resistant behaviors (i.e., talking back), as ghosts, they can blame their perpetrators, hold grudges, possess other women to express their anger, and even enact punishment on their assailants (who were oftentimes men) for their victimization. Resistance is significant, especially in response to victimization, because resistance by the sexualized female ghosts, “with their bruised bodies, can be translated into an expression of women’s unspoken words, about their sufferings and frustration under the severe oppression, and especially about the society’s neglect and despise of their female sexual bodies.”[21] Through a feminist perspective, we can begin to view the female ghost and the monstrous-feminine in ways that generate discussion on the issue of sexual violence and pivot the focus from patriarchal fears and perpetuation (of violence) to women expressing their stories of sexual violence and how we as a culture can address these issues. The portfolio of Japanese artist Yuko Tatsushima expresses these unspoken grievances of sexual violence through her depictions of disfigured and “monstrous” figures and disturbing imagery that draws parallels to traditional portrayals and descriptions of female ghosts in Japanese cultural media. As with stories like Oiwa and Okiku in their new context, Tatsushima’s portrayal of the monstrous-feminine of the Japanese female ghost becomes a space wherein femininity is redefined and reclaimed through visual storytelling and traditional symbolism.

YUKO TATSUSHIMA’S GHOSTLY MONSTERS

The work of Yuko Tatsushima is renowned for disturbing and graphic depictions of ghostly figures, which evoke visceral emotions in viewers, including discomfort, unease, allure, and empathy. From her use of dark and intense colors, scratched brushwork, and body horror imagery, many have associated her work with the horror genre on the surface level. However, Tatsushima’s portfolio captures the monstrous-feminine and essence of the Japanese female ghost, but in ways that subvert traditional patriarchal messaging of womanhood and femininity. Rather, her work embraces the grotesque, the horror, and the macabre to express, particularly, the horrors of sexual violence, abuse, and death, and the frustrations of the abuse culture in Japan. Much about Tatsushima is unknown, with the only available information on the artist coming from other online users who have referenced her work. Her website only contains the images of her paintings, and her X (formerly Twitter) account has remained inactive since 2019. Users online have stated that Tatsushima graduated from Joshibi University of Art and Design in 1998 and works as an artist, performer, and puppet artist of multiple disciplines. It has also been claimed that her work is intended to protest against sexual offenses, serving as self-portraits, and expressing her hardships surrounding the death of her mother and her diagnosis of borderline personality disorder, though, as of writing this, I cannot verify this information.[22] Regardless of this information’s validity, Tatsushima’s work undoubtedly centers on themes of sexual abuse, sexualization, and the monstrous-feminine as a means of expressing the unspoken sufferings, grievances, and frustrations of abuse against women.

Many of Tatsushima’s works share characteristics with the grotesque of the Japanese female ghost seen in older depictions. Some smaller shared characteristics include long black hair, pale white skin, burial depictions, white kimonos, and ghostly appearances and atmospheres, as seen in Figures 3 and 4.[23]

Figure 3. (left) - Hyakki Zukan, Sawaki Suushi, 1737

Figure 4 .(right) - “I can't get married anymore”, Yuko Tatsushima, 1999

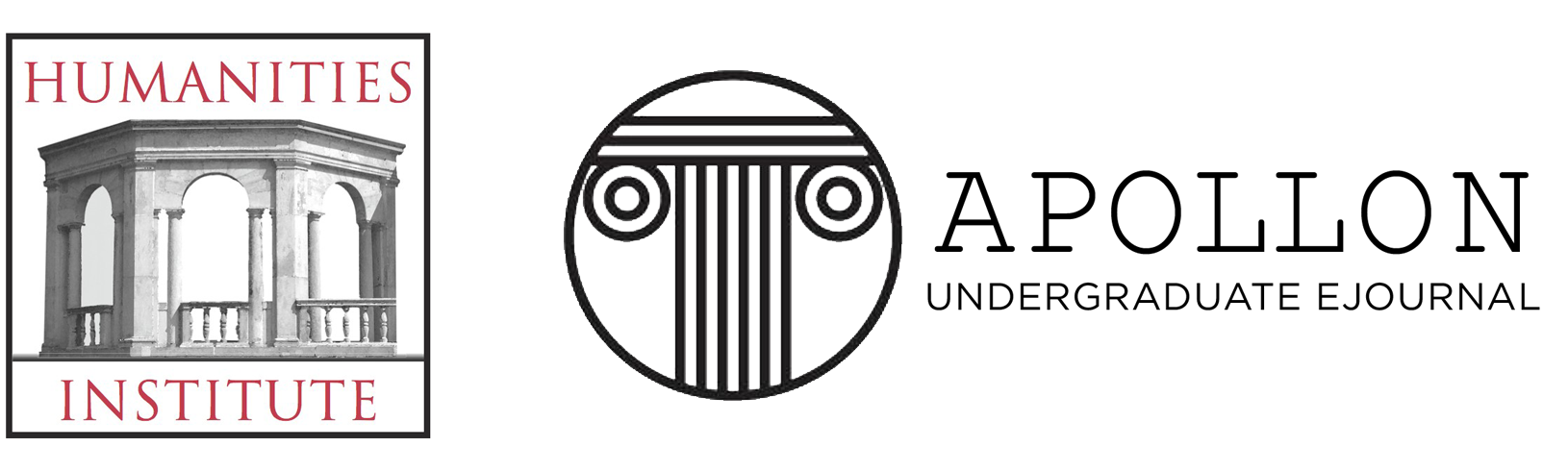

More significant parallels are depictions of the lack of legs and mutilation/disfigurement. Ikoma’s article titled “Why do Japanese Ghosts have No Legs?” emphasizes that “legless ghosts” and the grotesque disfigurement of the female ghost are symbols of fear of the “horrible death” resulting from murder, abandonment, neglect, sexual abuse, suicide, and other acts of violence to the body. Stories of the Slit-mouthed Woman, Kawanabe Kyōsai’s legless ghosts paintings, and the facial disfigurement of Oiwa share similar features with multiple paintings by Tatsushima. This is particularly evident in the piece Maria of Guraund Zero (2000), depicting a pale, limbless figure with a face marred by a painful-looking smile that nearly splits the face in half, as seen in Figure 5.[24]

Figure 5. Maria of Guraund Zero, Yuko Tatsushima, 2000

Figures 6 and 7, as shown below, also illustrate these characteristics. Figure 6 is Kawanabe Kyōsai’s Female Ghost (1871-1889).[25] Figure 7 is The Lantern Ghost (1831-1832), painted by Hokusai Katsushika.[26] Among other similarities, Tatsushima’s work draws inspiration from classic depictions of the Japanese female ghost in Japanese prints and stories to represent the themes discussed earlier.

Figure 6. (left) - Female Ghost (untitled), Kawanabe Kyōsai, 1871-1889, Meiji Period

Figure 7. (right) - The Ghost of Oiwa (The Lantern Ghost), Katsushika Hokusai, 1831-1832

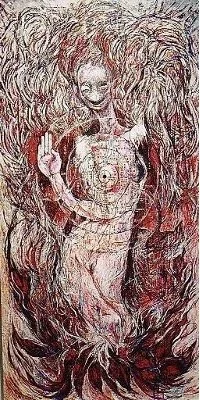

Tatsushima incorporates motifs and symbols in her work that portray stories of sexual abuse, death, and suffering. Their work portrays the horrific manifestations of sexual violence, pain, and suffering, but in ways that seem unique to Tatsushima. Harsh marks, along with a mixture of dark and vibrant colors, create a significant contrast that makes the figures stand out. The religious and spiritual symbols seem to emphasize the themes of death, grief, and the afterlife. What stands out most in works such as White Prison (2002), Lookout of Blood (2009), “I can’t get married anymore” (1999) – also translated as “I can’t be a bride anymore” – and her puppet work “Renna” (2001) and Tsyumi Tsyumi (date unknown) are depictions of bodily harm – self-inflicted or otherwise.[27] In the images below, consistent imagery of scratches, stitches, missing limbs, painful expressions, and other forms of disfigurement is eye-catching.

In White Prison and “I can’t get married anymore” (Figures 8 and 9 below), both figures have a similar appearance to the traditional Japanese female ghost previously discussed; however, White Prison portrays a figure with doll-like joints and missing legs. This may imply the sexualized and stereotypical portrayal of women/girls as dolls – oftentimes both “cute” and sexualized – that represents the societal roles expected of women, i.e., to do as they’re told, to appear and behave femininely, to be attractive, sensual, but not sexual, among other expectations stemming from purity culture. Dolls, in many traditional cultures, were believed to carry or possess souls. Despite the doll-likeness, the figure is covered in lacerations, implying the skin is real flesh. Chng Nicolette expresses that this gruesome inclusion may be a way to contrast the commercial image of the doll and serve as a testament to Tatsushima’s desire to “illustrate the corruption of femininity.”[28] Her red dress would be considered “revealing,” and the scratching/harm on her body is present on her thighs and chest. The scene is a funeral, where the items behind the figure show signs of a memorial.

Figure 8. (left) - White Prison, Yuko Tatsushima, 2002

Figure 9. (right) - “I can’t get married anymore,” Yuko Tatsushima, 1999

“I can’t get married anymore” displays more direct depictions of some form of sexual assault. Here stands a long figure who wears a white kimono with wide eyes and a dark smile on her face. At her crotch, the kimono seems to disappear, seemingly pulled back or ripped from the figure’s body. What it reveals is a body that has been completely scratched away, similar to the background. This painting may refer to the taboo of premarital sex, regardless of whether it was consensual or not, with these sexual relations being highly stigmatized and rendering a woman “unpure” and not fit to be married.”[30]

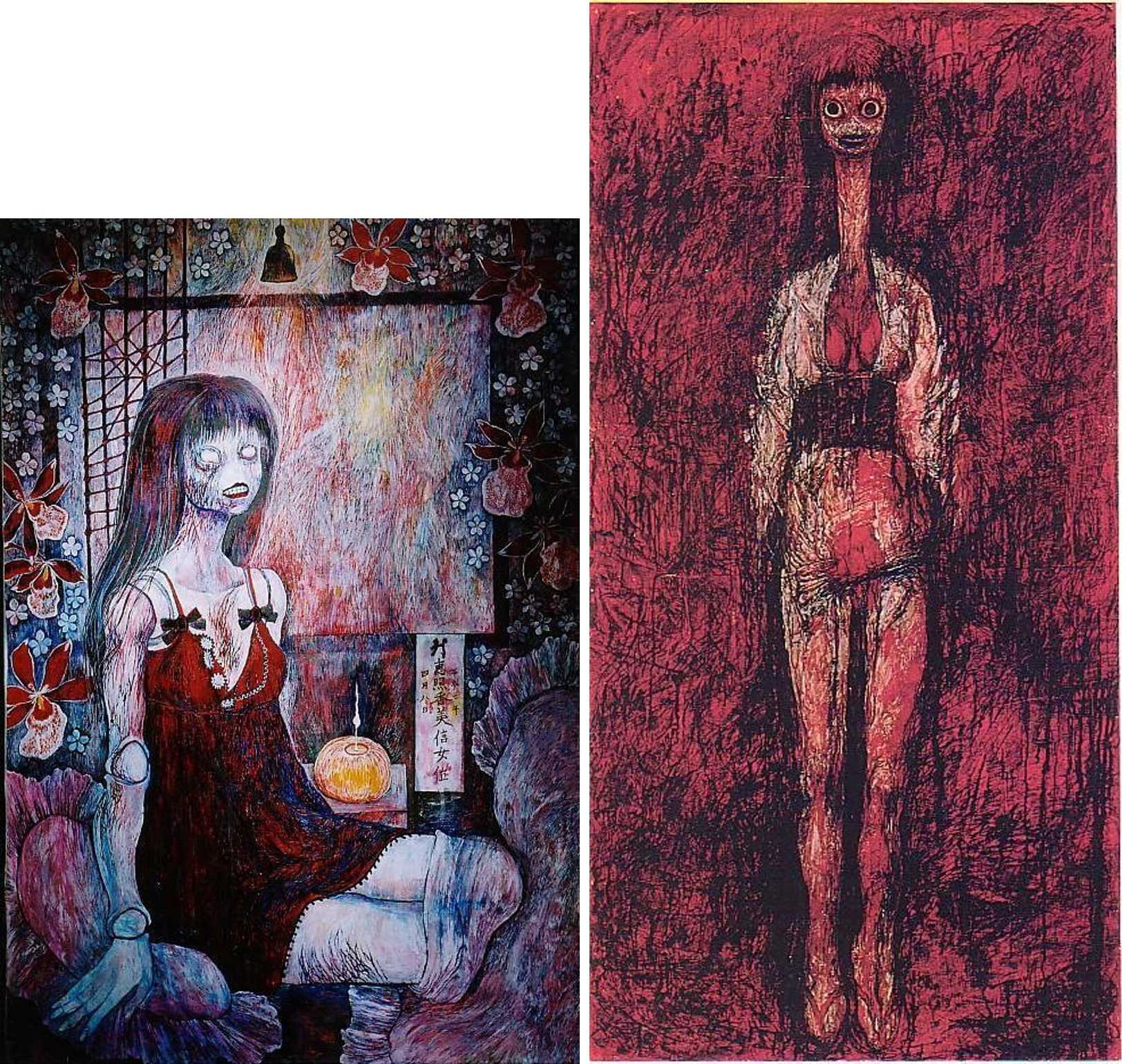

In Tatsushima’s painting Spring Night Insect Dream (2003), Figure 10, a child stands in front of a frame of orange flowers in a ripped red dress.[31] Her dress is ripped at the crotch area, and her arms are crossed over her chest. This painting strongly suggests a potential assault on the figure, who wears an expression that is almost frightened or dissociative. .

Figure 10. Spring Night Insect Dream, Yuko Tatsushima, 2003

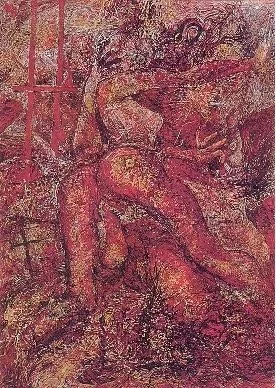

Tatsushima’s White Thread (1999) depicts a figure in a twisted position, with face, eyes, and sharp teeth abstracted into the background.[33] Figure 11 is below.

Figure 11. White Thread, Yuko Tatsushima, 1999

The figure also features one of the most recognizable motifs of the monstrous-feminine: the vagina dentata or toothed vagina, a literal representation of the femme castratrice. Creed describes the vagina dentata as “the mouth of hell” that “points to the duplicitous nature of woman, who promises paradise in order to ensnare her victims.”[34] The grotesque image of the vagina dentata embodies the horror of the dangers of a woman’s sexuality as it threatens men’s self-control, autonomy, and power.[35] To Creed, the vagina dentata is a symbolic characteristic of woman as castrator, which “points to male fears and fantasies about the female genitals as a trap, a black hole which threatens to swallow them up and cut them into pieces.”[36] However, the significance of the vagina dentata is that the teeth do not attack when sexual intercourse is done consensually; otherwise, the vagina dentata may be responsible for castration when the woman’s body is taken forcibly. This seems to be what is happening in White Thread, and the teeth of the vagina bite down on a phallic object. This phallic imagery seems to hold deeper implications on the nature of sex, pleasure, and pain.

CONCLUSION

Monstrosity in cultural mythologies and folklore often arises from the desire to disempower what is perceived as a threat to the social order and the potential collapse of society. Here, the conception of the female monster represents the patriarchy’s anxieties and abhorrence of female sexuality. The Japanese female ghost is marginalized, victimized, and sexualized in life as an object to be silenced and controlled. By creating these images, “the patriarchal society may have transferred onto women’s bodies its fear of mortality and sexuality, in an attempt to control them at the same time.”[37] In this light, the female ghosts represent the spectacle of horror, the grotesque, pain, the “horrible death,” victimhood, and negative stereotypes of the female body.

In a different light, however, the Japanese female ghost, in all its horror, sexualization, and disfigurement, can “translate into an expression of women’s unspoken words, about their sufferings and frustration under the severe oppression.” [38] The monstrous-feminine terrifies because it deconstructs traditional norms of gender and subverts the hegemony of a male-dominated society. Through Creed’s monstrous-feminine, the Japanese female ghost can become a symbol of resistance. Instead of being victims at the hands of male oppression, the Japanese female ghost is reenvisioned in the works of Yuko Tatsushima. The figures of Yuko Tatsushima’s work do not have to be regarded as only victims because of their sexuality and sexualization. Rather, these feminine monstrosities are the stories that can’t be told, the sufferings that are ignored, the frustrations that are unaddressed, and the resistance the patriarchy is terrified of. Through this expression of the unspoken, women can embrace the monstrous and continue dismantling the culture of rape and gender normativity that male society is so desperate to maintain.

Endnotes

2. Felton, “Rejecting and Embracing,” 105.

3. Sofia Sears and Eli Cohen, “Defining the Monstrous Feminine,” In Unwomen: The Monstrous-Feminine In Contemporary American Pop Culture, Scalar, Updated June 27, 2020, https://scalar.usc.edu/works/monstrousfeminine/defining,-the-monstrous-feminine.

4. Sofia Sears and Eli Cohen, “Defining the Monstrous Feminine.”

5. Natsumi Ikoma, “Why Do Japanese Ghosts Have No Legs? - Sexualized Female Ghosts and the Fear of Sexuality Natsumi Ikoma,” Dark Reflections, Monstrous Reflections: Essays on the Monster in Culture, 2008, 197.

6.Utagawa Kuniyoshi, Onoe Kikugoro III as the Ghost of Oiwa in the Play Yotsuya Kaidan, 1836, Woodblock print, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Yotsuya_Kaidan&oldid=1317242730. Hokusai Katsushika, Sarayashiki (The Plate Mansion), 1832-1831, Woodcut, color, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hokusai_Sarayashiki.jpg.

7.Hokusai Katsushika, Sarayashiki (The Plate Mansion), 1832-1831, Woodcut, color, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hokusai_Sarayashiki.jpg.

8.Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection. United States: Columbia University Press, 1980, 2.

9.Barbara Creed, The Monstrous-Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis, London; Routledge, 1993, 1.

10.Sigmund Freud, “Medusa’s Head,” The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, edited and translated by James Strachey, Vol. 18. (1940), 105-106.

11.Freud, “Medusa’s Head,” 105-106.

12.Rachel Dumas, The Monstrous-Feminine in Contemporary Japanese Popular Culture, Germany: Springer International Publishing, 2018, 18-19.

13.Dumas, The Monstrous-Feminine, 7.

14.Dumas, The Monstrous-Feminine, 449.

15.Dumas, The Monstrous-Feminine, 18.

16.Dumas, The Monstrous-Feminine, 9.

17.Tanaka Takako, “Yūrei wa naze onna bakari ka” [Why are there so many female ghosts in Japan?”], Yūrei no Shōtai [The True Identity of Ghosts] (Tokyo: Heibonsha, 1997), 44-70 in Samantha Landau, “Passionate Women, Vengeful Spirits: Female Ghosts and the Japanese Gothic Mode,” Manusya: Journal of Humanities 27, 1 (2024): 1-23, doi: https://doi.org/10.1163/26659077-20242723

18.Ikoma, “No Legs,” 198.

19.Ikoma, “No Legs,” 198.

20.Ikoma, “No Legs,” 198.

21.Ikoma, “No Legs,” 199.

22.@chappieee, “Yuko Tatsushima TW- gore in art.” Posted on Amino, November 2, 2021, https://aminoapps.com/c/horror/page/blog/yuko-tatsushima-tw-gore-in-art/V0Qt_7u3NRZQW8xPQaqvgqzbgj80Z4q.

23.Sawaki Sūshi, Yūrei Hyakki Zukan, 1737, Woodblock print, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Y%C5%ABrei-zu&oldid=1323307975; Yuko Tatsushima, あたしはもうお嫁にはいけません (I Can’t Get Married Anymore), September 29, 1999, http://undergroundfortress.web.fc2.com/kaiga/kaiga/1yome.html.

24.Yuko Tatsushima, 爆心地のマリア(Maria of Guraund Zero), June 30, 2000, http://undergroundfortress.web.fc2.com/kaiga/kaiga/1baku.html.

25.Kawanabe Kyōsai, Female Ghost (untitled), 1871-1889 (Meiji Era), Gold, Ink, 106.80 cm x 37.70 cm, The British Museum, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/A_1996-1010-0-1.

26.Hokusai Katsushika, Kabuki Actor Arashi Rikan II as Iemon Confronted by an Image of His Murdered Wife, Oiwa, on a Broken Lantern, 1832, Woodblock print, ink and color on paper, 14 7/8 × 10 1/8 in. (37.8 × 25.7 cm), The Metropolitan of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/76565.

27.Yuko Tatsushima, 白牢 (White Prison), July 21, 2002, http://undergroundfortress.web.fc2.com/kaiga/kaiga/1haku.html.

28.Chng Nicolette, “Yuko Tatsushima,” Medium, August 11, 2022, https://medium.com/@2202221d/yuko-tatsushima-7261ddd6ede2.

29.@Velata, “These Paintings Are Not Scary!/Yuko Tatsushimas Work Through a Lens of Sexuality and Sexual Assault,” Commented 6 months ago on YouTube video, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=teGjEurE4y4.

30.Nicolette, “Yuko Tatsushima.”

31.Yuko Tatsushima, 春の夜の虫の夢 (Spring Night Insect Dream), May 14, 2003, http://undergroundfortress.web.fc2.com/kaiga/kaiga/0haru.html.

32.ススル, dir., 立島夕子個展「毒の飴」TATSUSHIMA YUKO Exhibition「DOKUNOAME」, 2013, 15:54, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WRIw9_0Ui38.

33.Yuko Tatsushima, 白い糸 (White Thread), June 18, 1999, http://undergroundfortress.web.fc2.com/kaiga/kaiga/1siro.html.

34.Dumas, The Monstrous-Feminine, 432.

35.Margaret R. Miles, “Carnal Abominations: The Female Body as Grotesque” Edited by James Luther Adams and Wilson Yates (eds), The Grotesque in Art and Literature: Theological Reflections. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1997, 97.

36.Dumas, The Monstrous-Feminine, 366.

37.Ikoma, “Legless Ghosts and Female Grudge: Analysis of Japanese Ghosts,” 146.

38.Ikoma, “Why Do Japanese Ghosts Have No Legs?” 199.

Kayla Smith

Kayla Smith is a multidisciplinary artist, born and raised in Fort Worth, Texas. She is a recent graduate from the Maryland Institute College of Art. She graduated with an integrated Bachelor’s degree in General Fine Arts and Humanistic Studies and minors in Art History and Painting. Additionally, she is pursuing a second degree in biology and forensic science at Tarrant County College, where she is currently a student. Her academic studies explore a range of focuses, from the complexities of extremist human behavior and institutional corruption to the representations of monsters in cultural folklore as vehicles for resistance and institutional subversion.