Seventeenth-Century Dutch Animal Imagery Challenging Anthropocentrism: Paulus Potter’s Punishment of a Hunter

By Sofya Vorobeva, University of Tyumen

INTRODUCTION

In the painting Punishment of a Hunter, the Dutch seventeenth-century artist Paulus Potter depicted animals putting a hunter on trial and enacting a death sentence. Surrounded by smaller allegorical and hunting vignettes that show animals and humans, the animal court and hunter’s execution by burning appear in two central scenes. In the upper central scene, the guilty hunter appears at the forest’s edge in front of the animal court. His arms are tied behind his back, and two wolves hold the ends of the rope. A bear stands behind the hunter and holds him tightly. Other animals preside in the court, with the lion at the head, while the fox records the proceedings, enacting the death sentence. In the lower scene, the hunter is roasted on a brazier. Together a bear and a goat stand nearby with spoons, ready to taste the flesh of the guilty. In the cloud of smoke, two hounds hang from the tree and another two are waiting for their turn. Nearby, animals are dancing, celebrating justice over the hunter and his accomplices.

Figure 1

Paulus Potter. Punishment of a Hunter, c 1647 – 1650

Oil on wood panel, 84. 5 x 120 cm

The State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg

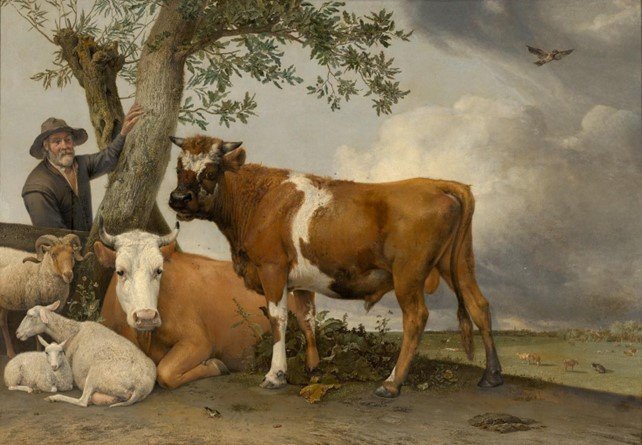

The painter, Paulus Potter, specialized in painting animals, especially domestic animals in Dutch pastures. Most of his works were animal portraits, the majority being stable with minimal actions. His famous The Bull (1647) represents all these key features of his style (fig. 2), including his tendency to give a human character to his animals and vice versa.[1]

Figure 2

Paulus Potter. The Bull, 1647

Oil on canvas, 235.5 cm x 339 cm

Mauritshuis, Den Haag, Netherlands

Punishment of a Hunter is distinct, both in terms of Potter’s other works and more broadly in Dutch seventeenth-century painting. The structure of the wood panel – fourteen scenes separated by black lines – was unusual for painting at that time and more common for printed engraving spreads. The level of activity on each scene stands out from the usual calm of Potter’s artworks. These two central scenes of trial and retribution raise questions about the conceptual and physical interrelations and commonalities between animals and humans. The smaller vignettes that surround the central scenes add context and moralizing narrative to the entire painting. The narrative and content of the artwork seem extraordinary for the seventeenth century for the contemporary viewer by its content and form. This painting turns power relations upside down, questions human superiority over other animals, and reflects on animal subjectivity. Even more remarkable and paradoxical is that this painting of animal consciousness and power was produced in the same era when humanist philosopher, René Descartes, developed his concept of mind-body dualism to define the human and proclaimed animals as reasonless automata. Therefore, the painting decentralizes the human at the origin of Cartesian thought where logos and sensitivity distinguishes humans from animals, well ahead of contemporary animal studies theories.

Piers Beirne and Janine Janssen, in their essay “Hunting Worlds Turned Upside Down,” apply a cultural criminology approach to examine the possible meanings that Potter invested in his painting.[2] Beirne and Janssen propose that it could be a satire on animal trials, a commentary on the political situation, or an expression of contempt for animal cruelty. They could not claim that any one of these readings are the most accurate because they lacked evidence, awareness and knowledge of Potter’s views.[3] Beirne and Janssen initially supposed that Potter’s painting condemns animal cruelty, but they could not develop this investigation because they believed that these views were not typical for the seventeenth century.

Instead, this paper concentrates not on the historical context of Potter’s artwork but on messages that people in the seventeenth century may have perceived in this painting and what insights they may provide to present-day viewers. This approach might be more fruitful since it does not depend on Potter’s ideas and thoughts. Beirne and Janssen’s paper shows a gap in the body of research concerning the interpretations of how this painting was perceived through different epochs. Hence, in the analysis of Potter’s artwork, this paper will build upon Nathaniel Wolloch’s approach, presented in his paper “Dead Animals and the Beast-Machine,” of situating Dutch seventeenth-century paintings within the central philosophical ideas about humans and animals at that time and examine Descartes’ and Montaigne’s ideas in more detail in order to provide a contextualized reading of the painting.[4] Additionally, the contemporary philosophy is applied to analyze the artwork through the prism of questions about anthropocentrism, animal subjectivity, and their status in philosophical concepts.

Building upon this body of ideas, Punishment of a Hunter is interpreted as a satire on cruel hunting and a metaphorical statement that challenges human mastery over animals and decentralizes humans from a position of mastery. In arguing for this interpretation, the research will begin with formal and iconographic analysis of the painting. Building upon this analysis, the painting’s message is contextualized in the central philosophical ideas about human-animal relationships in both seventeenth-century philosophy and in the recently established field of animal studies.

A SATIRE ON HUNTING

Comprising of fourteen scenes separated by drawn thin frames, the entire painting measures 84.5 x 120 cm. It consists of twelve small side-scenes and two larger central ones. For a comparatively small canvas, there are numerous figures arranged into different scenes. There are four types of images: allegories, a portrait, hunting scenes, and the central climatic episodes. This analysis will concentrate on the role of these images in the construction of the painting’s complex message.

Figure 1

Paulus Potter. Punishment of a Hunter, c 1647 – 1650

Oil on wood panel, 84.5 x 120 cm

The State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg

The relationship between the side and central scenes play a key role in creating meaning. While we are first drawn to the central images due to their size, location and the density of figures, the smaller side scenes are essential for interpreting the central ones. The painting’s format resembles that of a polyptych, which often feature larger central panels surrounded by smaller secondary ones (fig. 3). However, they typically have a chronological order that helps to create narrative structure.[5] In the case of religious polyptychs, this complex structure is implemented in conjunction with highly moralizing religious iconography. Moreover, polyptychs are constructed from separate connected panels, while Punishment of a Hunter is a single wood panel with painted lines that separate scenes.

Figure 3

Jan van Eyck. The Ghent Altarpiece (open view), 1432

Oil on wood panel, 520 x 375 cm

Saint Bavo’s cathedral, Ghent, Belgium.

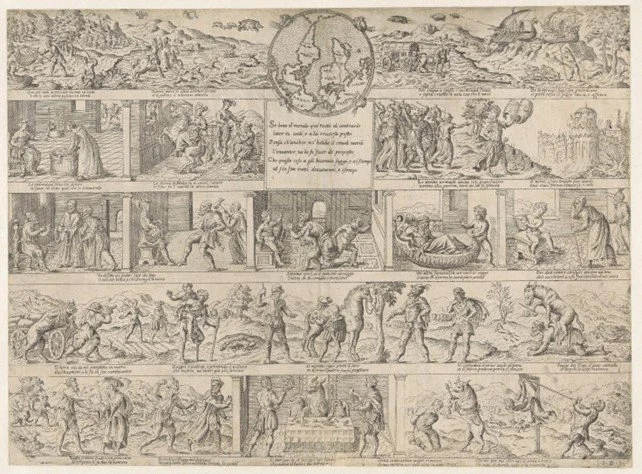

The structure of the painting also resembles the popular European tradition of “World Upside Down” (WUD) broadsheets, in which the world order is depicted in reverse. WUDs are satirical graphic works that ridicule ordinary things or show the oppressed in positions of power (fig. 4). WUDs are often accompanied by text that explains the scenes, an inverted globe or world map, and the title “World Upside Down.”.[6] Punishment of a Hunter employs some of the key features of the WUD to create a similar satirical effect and like the broadsheets, it features separate scenes. Notably, human and animal roles are often reversed in these prints. Indeed, one possible source for Punishment of a Hunter is the etching Topsy-Turvy World (c. 1580-1600) by Ioan Galle (fig. 5).[7] It seems to combine both scenes depicted in Potter’s work – a bound hunter appearing before a court in the foreground, and the brazier and dogs hanged in the background. Hence, the inheritance of the WUD tradition in Potter’s work becomes clear, since it inherits its structure, and the same plot was executed before in Galle’s WUD.

Figure 4

Etienne Dupérac. Verkeerde wereld, c 1560

Printed etching on paper, 37.1 cm x 50.8 cm

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Figure 5

Ioan Galle. Topsy-Turvy World, c 1580 – 1600

Printed etching on paper, 21 cm x 29.8 cm

Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, Netherlands

The surrounding scenes provide a broader context for understanding the images of punishment. Three upper vignettes set up a moral frame for interpreting the central images. The upper left scene depicts the hunter Saint Hubert kneeling before a stag, who appears with a crucifix between his antlers. After this vision, St. Hubert preached that one should hunt animals humanely because they are also creations of God and capable of suffering.[8] The upper right scene, which was painted by Cornelis van Poelenburgh, depicts the myth of Diana and Actaeon.[9] It tells the story of Actaeon, the hunter who accidentally encountered Diana, the goddess of the hunt, naked and enjoying a bath with her nymphs. As punishment for seeing her virtuous body naked, she transformed him into a stag. The painting depicts the start of the hunter’s transformation; a figure with antlers fleeing in panic. At the end of the myth, Acteon is killed by his hounds, who fail to recognize him. Between these scenes, Potter depicts the portrait of the hunter in refined clothes with prey and two hounds against a traditional Dutch landscape. In this scene, the hunter appears as the owner of the land and master of Nature. However, the two flanking moralizing narratives question his status. The legend of St. Hubert teaches that in Christian cosmology, morally permissible hunting is practiced out of need and not out of greed or demonstration of power. Diana and Actaeon’s myth show in a metaphorical way that the hunter can become a prey one day. These two allegorical images with a portrait of the hunter in between raise the tenuousness of animal-human distinction. They stress the closeness of humans to animals via the metamorphoses of Christ-stag and hunter-stag, and thus question human exceptionalism and mastery over animals.

Two types of hunting scenes appear to the left and right sides as well as at the bottom. The first demonstrates traditional hunting methods, such as hiding in the landscape with a gun or using traps. The second type presents the hunt as a battle, not a strategic practice. Cornelis Hofstede de Groot claims that these scenes are caricatures of Peter Paul Rubens’ hunting scenes and this can be confirmed by comparing the composition and plasticity of figures between Potter’s scenes and Rubens’ painting (fig. 6).[10] Indeed, Potter references Rubens by depicting exotic animals, hunters in turbans, and the use of swords and long-distance weapons in a close battle, something that no real hunter would use in this way. These scenes highlight the damage done to animals and humans. Hounds bite prey – the latter respond by ripping dogs and hunters apart. In the lion and wolf hunts, people pierce the animals with spears and pitchforks. On the one hand, these battle hunting scenes, alongside the traditional ones, stress the cruelty of the process, as well as presenting animals and hunters in more equal positions. Like prey, the hunters and hounds are also wounded during the battle.

Figure 6

Peter Paul Rubens. Meleagr and Atalanta Hunting, mid-1630s.

Oil on paper pasted on canvas, 316 x 622 cm.

The State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg

In the central upper scene, Potter depicts the animals putting the hunter on trial. The lion presides as judge and other animals serve as officers and guards. The hunter bows his head before the lion and receives his judgment. In the background, four hounds wait their turn. Below, the sentence is carried out. The hunter is roasted on a brazier while the goat and boar are ready with the spoons to eat him. Two hounds hang from the tree, while a third accomplice waits their turn. On the right side, animals dance in celebration of justice. These climactic scenes attract attention not only because of their size and density of figures but also due to the colors (e.g. a black cloud of smoke below and golden sunlight above). Framed by previous scenes, we can understand that the hunter received his retributive justice for causing much suffering to animals. In the center, the animals act like humans. They do not kill like wild animals; but they do it like humans – by trial and execution. Notably, this painting does not have a singular hero. In each scene, the hunters are depicted with different faces, styles of clothes, horses, and hounds. Thus, the hunter in the center is not an individual but an archetype. His execution symbolizes the punishment of all cruel hunters.

The formal elements of the artwork support the WUD-like structure of the painting. Unlike Potter’s other paintings, Punishment of a Hunter is dense with figures of animals and humans in action.[11] Some animal poses and actions seem unnatural and anthropomorphic: a lion with a scepter, a fox holding a scroll, and dancing animals. Along with the battle-hunting scenes, these poses introduce a satirical aspect that coincides with the tradition of the world in reverse imagery. Moreover, the more conventional images of human-animal interactions on the sides of the painting reinforce the satirical essence of the central scenes. Providing a frame for the satirical images, the side scenes stress the cruelty and excessiveness of the hunts. Hence, the structure and formal elements of the painting enhance the satirical commentary on unethical ways of hunting.

Therefore, Punishment of a Hunter is a satire on cruel hunting and a metaphorical statement that challenges human mastery over animals and decentralizes humans. The analysis shows how side-scenes provide the moralizing context for central ones through the composition of the painting. The painting reminds the viewers that hunters can also be prey for some animals and suggests that all creatures are equal in their rights for co-existence in the world.

ANIMALS IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY THOUGHT

Punishment of a Hunter presents a complex message on the essence of the relations between humans and animals. In the seventeenth century, two major debates on animals centered around their cognitive abilities. The first was presented in the writings of Michel de Montaigne, a prominent sixteenth-century writer and philosopher. Even a century later, his thoughts were influential and were mainly articulated in the work of his disciples, such as Pierre Charron.[12]

American philosopher, George Boas in his book The Happy Beast in French Thought of the Seventeenth Century (1933), introduces the notion of “theriophily” – the idea that animals are superior to humans. He argues that this concept is rooted in primitivism and observes that some thinkers concentrated on ancient (or primitivist) cultures like the Scythians and Hyperboreans. Some extended it to cultures that Europeans encountered during the period of exploration of the world. Simultaneously, as Boas puts it, other thinkers turned their attention to animals as an extreme point in primitivism, believing that animals are more “natural” than human beings. Boas identifies this belief as theriophily. He states that some theriophilist thinkers argue that animals are better than humans because the former is better adapted for wilderness and are not perverted with intellect. This follows the same primitivist logic, in which “civilized people” are perceived as inferior to “savages.” However, other thinkers objected to the basic theriophilist claim by arguing that animals also have different forms of cognitive abilities, and it does not make them inferior to humans.[13] Boas identified Pierre Charron as the most prominent theriophilist and explored the origins of his views in Montaigne’s essays.

Boas claims that the essay “Of Cannibals” (1603) presents Montaigne’s primitivism or Theriophily in a better way. In this text, Montaigne affirms that savages are not more barbarous than civilized people but more natural.[14] Then, Boas shows that Montaigne despised human intelligence and pride. However, Boas cautions the reader not to interpret Montaigne’s works only through the lenses of animal superiority over humans because the French philosopher also wrote some statements that presented the opposite view. Boas argues that these opinions and statements were not peculiar to Montaigne, who was influenced by the literary tradition of paradoxes.[15] In the texts where he raised the question of human-animal relations, Montaigne stated that nature gave people and animals an equal means of defense. He claims that all creatures have unique ways of interacting with the world, and comparison of human features with animalistic traits does not provide a basis for claiming that one group is superior to another.[16] However, some of Montaigne’s followers and readers have interpreted his comparisons between animals and humans in the discussed texts as an assertion of animal superiority over humans.[17] They tend to focus on the passages where Montaigne states that intelligence is evil, animal instincts might be more divine than rational human acts, and animals are nobler than people because they do not have servants and slaves.

On the whole, the attitudes of Montaigne’s disciples towards animals were criticized and attacked by Descartes’ followers. Both sides had different points of view over the claim that animals are reasonless automata, which Descartes presented in his book Meditations on First Philosophy. Building upon this claim, Descartes’s readers concluded that if animals cannot think and are deprived of self-consciousness, then they are non-sentient beings. In his text “Descartes on Animals,” Peter Harrison examined Descartes’s original text, his replies on letters with the questions about animals’ cognitive abilities, and other interpretations of the philosopher’s position. Harrison starts his text from John Cottingham’s reading of Descartes’s text where he asserts that attentive, close reading shows that Descartes did not deny animals ability to feel. Furthermore, Descartes’ understandings of feeling and thinking seem deceptive and confusing. Since, according to Cottingham “feeling [sentire] is no other thing than thinking.”[18] In this passage, Descartes clearly states that feeling is one of the cognitive abilities – thinking – that is tightly connected with self-consciousness. However, this does not mean that Descartes’ denial of animal self-consciousness necessarily leads to the inability to feel. As Cottingham notes, Descartes employs two distinct terms that are both translated into English as “feeling” but mean slightly different things: sentire and passions. Sentire is the feeling that requires self-consciousness and cognitive abilities that Descartes denied to animals. In contrast, passions do not depend on thought or self-consciousness, and they may be found in animal behavior (i.e., fear, hunger, and joy).[19] Thus, Descartes did not deny all animal feelings.

Moreover, Harrison argues that the concept of souls is crucial for an understanding of feelings. Descartes’ understanding of souls derives from Aristotelian differentiation of them: vegetative (plant) souls, sensitive (animal) souls, and rational (human) souls. Descartes claimed that there are two types of movement: corporeal and mechanical (sensitive) versus incorporeal and rational. He considered animal movements to be mechanical because they lacked self-consciousness or rational souls. Harrison pays attention to the fact that Descartes, in his Meditations, “established rational grounds for belief in God, other minds, and the external world.”[20] In other words, for Descartes, rationality is tightly connected with spirituality. Harrison shows that Descartes in his letters claims that he cannot be certain if animal souls encompass spiritual actions, and that he did not deny that animals have the ability to feel pain.[21] Hence, for Descartes, since he could not be certain whether animal cognition is similar on a spiritual level to human one, it was better to claim that animal activities are mechanical ones.

The analysis of the seventeenth-century central attitudes towards animals, shows that readings of Descartes and Montaigne done by their disciples produced polar understandings of animals’ abilities and nature. Yet, close consideration of the original texts suggests that people and animals have more in common than it was stated by the texts subsequent to Descartes and Montaigne. Drawing upon this, this analysis will focus on human and animal range of feelings from pain to pleasure, and their interactions with the environment they live in together and with each other. Through these lenses, Punishment of a Hunter can be viewed as a warning that people and animals are equal in their interactions with the environment and their abilities to feel (passion) the effects of living in this world.

TURNING FROM HUMAN TO ANIMAL

While Descartes and Montaigne, placed the human in the center of their studies and animality is used as an instrument to define human nature and the features of being human, Jacques Derrida criticizes this approach. In his book The Animal That Therefore I Am (2006), he examines the great divide in western thought between humans and animals, arguing that earlier philosophers ignored animals as the objects of study and their influence on the construction of ideas about humans. He uses a structuralist approach to address the history of the cultural separation of the category of animal from the category of human, and the nature of this division in culture. Derrida’s ideas had a major impact on other philosophers, and this text is perceived as a turning point in contemporary animal studies. Interest in animality – and not humanism – is one of the crucial differences between contemporary theories and those of the seventeenth century. Donna Haraway, a philosopher influenced by Derrida, criticizes the idea that the human is the central figure in the world in Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (2016). This book considers ideas about human-animal interactions in a dimension of conceptual thinking over power and world order. Their ideas will be applied to formulate a contemporary interpretation of Potter’s artwork.

In his text, Derrida presents the idea of the great divide between animals and humans. He examines ideas presented in different cultural objects, such as the Book of Genesis, works of literature, and philosophical texts. All these sources share a common separation of humankind from the diversity of other species called “animals.” He criticizes this binary opposition between two categories because it creates an abyss between them in our comprehension and deters the development of a more complex understanding of humans and animals. Derrida argues that this oversimplification is even more harmful to the comprehension of animals because, under this abstract group, the incredible diversity of living beings is homogenized. It creates an obstacle for thinking about possible interconnections and relations between animals and humans.[22] On the other hand, he claims that even though people and animals are not separate homogeneous groups, they can be united over the violent and ignorant attitude of humans to other species. Moreover, he highlights the paradox that this kind of attitude comes from species being divided into human and non-human groups. Hence, he argues that the “animal” category is a crime against animal species.[23] Following this same logic, we may consider Potter’s Punishment of a Hunter as an opposite case because it unites all the hunters in the world under the category of “hunter.” The painting may be interpreted in two ways: it shows that humans might be a mere “prey” category for predators, or it shows hunters in the animal position, as animals being killed only because they belong to the non-human category. In other words, if we assume for a moment that the hunter in the center is not an archetype but an individual, animals execute him regardless of his deeds but because he belongs to the category of “non-animal” abusers. This message, in effect, creates a crime against humanity.

Derrida also provides a close reading of Descartes and criticizes him for his logocentric approach to ontology: to exist and have an ability to respond, one needs to have self-consciousness. Derrida argues that Descartes’ approach excludes possible ways of comprehending animal responses because this logic is developed from human perception in opposition to animality.[24] Moreover, he claims that the animal point of view is missing from the discourse because it is the product of human reason.[25] Therefore, existing discourse over human-animal relations limits our comprehension of communication to the abilities of Homo sapiens and does not consider alternative ways of interacting with each other.

From this perspective, Punishment of a Hunter allows viewers to reflect upon the possibility of animal responses to human actions. In this painting, the animals have their own point of view on excessive hunting and response to it, which allows us to rethink the content of the painting from the animal’s perspective. On the other hand, this painting shows us the limitation of human understanding of the animal point of view. Potter’s animals act according to European human customs – they do not kill the hunter in the manner of predators, they do it like humans by means of trial and execution. Nonetheless, the moralizing narratives suggest different ways of interaction between humans and animals, by revealing animal pain, which is ignored by humans.

In Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene, Donna Haraway criticizes the concept of “the Anthropocene,” which presents humans as comparable to a major geological force that changes nature and to a planetary force that has power over other forms of life. She argues that this concept promotes human exceptionalism and presents humans as the key force that changes the world. To counteract the shortcomings of this concept, she proposes to switch the primary focus away from the human species and instead to consider them as part of the enormous web of interactions between the diversity of living beings.[26] Moreover, she argues that the Anthropocene is a harmful concept for humans considering ecological crisis because it presents humans as villains who will destroy Earth and all life, including themselves. She proposes to accept the troubles that people caused to the world and take responsibility for it. She argues that people need to abandon apocalyptic thinking as seemingly unavoidable and maintain a more responsible way of living and acting together with other living and nonliving actors on Earth.[27] She does not relieve humans from responsibility for the climate disaster, but rather proposes to rethink our place in the ecosystem and loss of hope in case of preventive actions. In the context of Potter’s painting, Haraway’s approach supports the painting’s message, which overthrows human supremacy over animals. In this light, Potter presents humans as villains who kill animals for amusement and bring disbalance to biodiversity. The animal trial reminds us that people cannot abuse nature eternally because people are not separate from the tight web of interspecies interactions.

Therefore, contemporary animal studies try to abandon anthropocentric logic and propose conceptions that allow consideration of other species at play. Both Derrida and Haraway recognize animals’ ability to respond to human actions. This analysis allows us to see the painting’s message as a warning for people that they are not the masters of nature; that this mastery harms and limits the perception of the world and interaction with it.

CONCLUSION

Given the preceding arguments, initially, Punishment of a Hunter, seems to condemn animal suffering, which is a rather unconventional message for the seventeenth century. Formal and iconographic analysis shows that this painting is a satire on cruel hunting. Even though the artwork does not condemn all forms of hunting, it clearly presents moralizing narratives that label excessive hunting as wrong and highlights the tenuousness of the distinction between animal and human. Descartes and Montaigne’s ideas support this point by recognizing that animals deserve equal consideration in discussions about pain and interspecies interactions. These statements dispel contemporary misconceptions about the perception of human-animal relationships in the seventeenth century. By abandoning anthropocentric logic, contemporary animal studies reveal the painting’s attempt to show hunting from the point of view of the animals. This context adds to the moralizing message that people are not the masters of nature and that the arbitrary exercising of power over animals will eventually end tragically for all living beings. This approach allows us to reflect upon our cultural and physical attitudes to animals and to consider more ethical ways of interaction with our sentient neighbors.

Therefore, Punishment of a Hunter challenges the anthropocentrism that is dominant in Western culture. Both in the seventeenth century and today, it proposes alternative ways of perceiving hunting and interacting with animals. The painting decentralizes humans from the position of mastery over nature and proclaims ethical methods of hunting.

Endnotes

[1] Hofstede de Groot and Hawke, 583–85.

[2] Beirne and Janssen, “Hunting Worlds Turned Upside Down?,” 49–69.

[3] Beirne and Janssen, 22, 23, 25, 26.

[4] Nathaniel Wolloch, “Dead Animals and the Beast-Machine: Seventeenth-Century Netherlandish Paintings of Dead Animals, as Anti-Cartesian Statements,” Art History 22, no. 5 (1999): 705–27, https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8365.00183.

[5] Dustin Garnet, “Polyptych Construction as Historical Methodology: An Intertextual Approach to the Stories of Central Technical School’s Past,” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 28, no. 8 (September 14, 2015): 955, https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2014.933911.

[6] David Kunzle, “Bruegel’s Proverb Painting and the World Upside Down,” The Art Bulletin 59, no. 2 (June 1977): 198, https://doi.org/10.1080/00043079.1977.10787404.

[7] Here I would like to thank my supervisor Erika Wolf for drawing my attention to this image.

[8] Like in the Bernie and Janssen paper, sometimes the figure of St. Hubert is confused with the St. Eustace. However, unlike Eustace, as the devotional figure, Hubert wears robes, and as the patron saint of hunters, he has a hunting horn. Moreover, unlike Eustace, he appears only in the art of northern Europe after the sixteenth century; Beirne and Janssen, “Hunting Worlds Turned Upside Down?,” 19; James Hall, Dictionary of Subjects and Symbols in Art, ed. Kenneth Clark, Icon Editions (New York: Harper & Row, 1974), 158.

[9] Hofstede de Groot and Hawke, “Paulus Potter,” 590.

[10] Hofstede de Groot and Hawke, 592.

[11] Hofstede de Groot and Hawke, 583.

[12] George Boas, The Happy Beast in French Thought of the Seventeenth Century (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins press, 1933), 2, http://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.$b685327.

[13] Boas, 1–2.

[14] Boas, 3; Villey,“Les Essais” de Michel de Montaigne, I xxxi, I 256.

[15] Boas, 9.

[16] Boas, 4, 19; Villey, II xii f. 181-205, 214 f.

[17] Boas, 4, 9.

[18] Harrison, “Descartes On Animals,” 222.

[19] Harrison, 222, 225.

[20] Harrison, 223, 224, 226.

[21] Harrison, 226.

[22] Jacques Derrida, The Animal That Therefore I Am, ed. Marie-Louise Mallet (New York: Fordham University Press, 2008), 33, 47.

[23] Derrida, 48.

[24] Derrida, 87.

[25] Derrida, 11.

[26] Donna Jeanne Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016), 49.

[27] Haraway, 2, 49.