A Matter of Public Opinion: How The Jamestown Exposition Built Naval Station Norfolk

Introduction

While the citizens of the Hampton Roads area today are prideful of being the home of Naval Station Norfolk––the the world's largest naval base , it was not always a welcoming location for sailors. Before World War I, sailors would come to Norfolk and be greeted with signs saying, "Sailors and Dogs – Keep off the grass."[1] When Norfolk won the bid to be the host of an international fair, the Jamestown Exposition of 1907, citizens were upset to learn that the federal government militarized the event by including various military displays and naval demonstrations.[2] However, after the exposition, public opinion shifted from seeing sailors as a nuisance to seeing how beneficial a permanent military presence in the area could be to Norfolk. This article shows how the military displays at the Jamestown Exposition of 1907 pivotally influenced the opinions of citizens of the Hampton Roads area to advocate for the establishment of a new naval base.

From 1907 to 1917, the exposition grounds remained empty, not because investors did not want to reopen the grounds but because of the backlash from citizens when the legacy of the exposition was threatened for a "catch-penny" amusement park.[3] As early as 1907, officers of the Jamestown Exposition Board of Officials started petitioning the Navy Department and Congress to purchase the land for a new naval installation. Local Virginian newspapers also began writing articles to persuade the Senate to choose Norfolk and buy the grounds, indicating a drastic shift from trying to keep the military out of Norfolk to asking Congress to bring the Navy back permanently.

Historians have recognized that the Jamestown Exposition of 1907 was a significant part of the decision to build Naval Station Norfolk at Sewell’s Point in Norfolk, Virginia, but they largely attribute this to purely economic reasons. The Jamestown Exposition of 1907 was intended to be an international fair celebrating the military strength and economic success of the United States after the Civil War era. The Exposition introduced the world to the Hampton Roads area by showcasing impressive military displays as the primary attractions.[4] Historians have attribute the subsequent financial disaster caused by the Jamestown Exposition of 1907 as the sole reason for the decision to build the Atlantic Fleet Headquarters on the same land in 1917.[5]

This article takes a new approach by examining the role of the citizens of Hampton Roads in the building of the base in Norfolk. The level of advocacy demonstrated by the people of Norfolk to turn the area into a naval operating base after the Jamestown Exposition indicates a change of sentiment from the previous negative association made with the Navy and its sailors. If the citizens had not actively advocated for a base for almost a decade, Congress would likely have supported the cheapest option without much discussion. Instead, the most influential factor in the decision for Norfolk to be selected as the site for a naval base was how the military displays at the Jamestown Exposition caused the citizens of Hampton Roads to change their opinion about keeping a military presence in the area.

Figure 1. 9 Flattops at Norfolk Naval Base, December 20, 2012. Photograph. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:9_Flattops_at_Norfolk_Naval_Base,_December_20,_2012.jpg

Norfolk vs. The Navy

In order to understand the shift of public opinion among the citizens of Norfolk and the rest of the Hampton Roads area, it is necessary to first consider the people's sentiment before the Jamestown Exposition. Like many other sailor towns in this period, citizens appreciated the economic boost that being a port city brought. However, they did not care for the seamen and sailors that came with it. While there is debate whether the "Sailors and Dogs – Keep off the grass" signs ever existed, several sailors of the period testified that they were prevalent. The sailors shared the same negative opinion of docking in Norfolk.[6] Citizens were wary of the sailors that came to port, holding fast that sailors of this period were of the same caliber as the pirates that plagued the coasts decades before. Published in the Norfolk Dispatch newspaper in 1903, a small section is dedicated to an article asking, "What People Think of the U.S. Navy," to which the author states, "a good many people think more of a dog than they do of a sailor."[7] While this may seem like a harsh statement, it is not hard to imagine that this was a common perception of sailors when, just six months after this article was published, the Norfolk Journal of Commerce reported that a "Barrel of Alcohol Stolen by Sailors Exploded on Deck" on the Cruiser Olympia in the Newport News shipyard.[8] With stories like this in the papers, as well as the persistent association of drunk and disorderly sailors pillaging towns after months at sea, it is not difficult to see where the negative public opinion of sailors came from and why citizens of Hampton Roads wanted them out.

Upon winning the bid to host the Jamestown Exposition of 1907, Hampton Roads citizens were alarmed to learn that the exposition would not merely be the tercentennial celebration of the establishment of the Jamestown Settlement but the largest military celebration in the world to date. It was hardly up to the citizens of Norfolk to militarize this event; instead, it had already been fully supported by President Theodore Roosevelt and Congress. President Roosevelt had already sent invitations to several foreign navies to request their attendance and bring their naval vessels to participate in various naval displays and contests.[9] Although the government highly supported the events, several public oppositions were made. In an article published in the Advocate of Peace, there was a fiery article condemning the militarism of the event, the extravagance associated with the exposition, and its dismissal of the historical reason for the celebration in the first place. The authors, fifteen named writers and other members of the Exposition Advisory Board, said that the exposition was "encouraging a notion that war is a thing of splendor" and the program proposed was drastically different than the one Congress just granted financial support.[10] The funding of this exposition had been controversial to the point that a candidate for lieutenant governor in Norfolk, Mr. William Kent, took the stance that the appropriation of $200,000 for the exposition was a waste and should have been given to education in support of supplying schoolbooks to children.[11] With the already negative association of sailors and the forceful militarization of the exposition, the lack of support for the Jamestown Exposition cannot be understated, especially when coupled with the desperate calls for support when the plans were underway.

The reason the appropriation was needed to support the funding of the Jamestown Exposition of 1907 is because Virginia was having issues with funding, primarily due to a lack of support from the average citizens. The Jamestown Exposition Company required one million dollars to be subscribed to the exposition in order to retain the charter and move forward.[12] The board constantly took out notices in local newspapers in order to entice investors and garner support for the event. The numerous articles written asking for the purchase of stocks indicate that there was a requirement to persuade citizens. In The Norfolk Landmark article from September 13th, 1903, the article encourages people to invest in the exposition by providing quotes from several prominent companies and business leaders who are supportive and have invested.[13] Not only is the article making the investment seem like a financially sound decision, but it is also calling into question the pride of the citizens in Virginia and the desire to be an industrially progressive city. The Jamestown Exposition had been marketed as a fantastic opportunity for Norfolk and the Hampton Roads area to mark "the turning point when Norfolk put off her waddling clothes and baby curls" and be put on the map.[14]

Through these efforts, the charter finally reached the one million dollar requirement in January of 1904.[15] The near failure of the Jamestown Exposition Company to achieve their initial financial requirements to start the project indicates that the citizens of the Hampton Roads area were not eager to be the site of the world's largest military display. Although efforts to become the site of the exposition had been fiercely advocated for, once the militarization of the event was evident, public interest and support dwindled. The constant publication of articles attempting to generate support, even with promises of extreme economic success and international attention, indicates the general public's negative connotation towards a military presence at this time.

Figure 2. Jamestown Exposition Stock. Photograph. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jamestown_Exposition_Stock.jpg

Sailors And Ships At The Exposition

Although citizens were not thrilled with the military aspect, due to the international attention given to the exposition, the city was determined to provide an excellent experience for the crowds and make a name for the Hampton Roads area. Copies of The Tidewater Cities of Hampton Roads Virginia Your Host for 1907 Jamestown Exposition, were sent off to as many people as possible, providing all the necessary background information for spectators and attendees to travel to the event, which would run from April 26th through November 30th.[16] Kicking off the exposition with a naval demonstration of all the fleets in attendance, a 300 gun salute, and President Theodore Roosevelt pressing a golden button, the crowds gathered in such a large quantity that there were no accommodations within ten miles.[17] Despite the efforts to provide special trains to the exposition grounds and the doubling of steamboat operations, Norfolk was not prepared for the thousands of people that flooded the city.[18] At the opening day's close, the warships at the docks were illuminated in thousands of glistening lights and the general public came to the same consensus: it was one of the most gorgeous displays ever witnessed. Suddenly, the perception of the militarization of the Jamestown Exposition changed from abhorrence to admiration as citizens admired the “fairy ships” in Chesapeake Bay. The event became so popular that, at the request of the citizens, the exposition made the ships' illumination occur multiple times throughout the event.

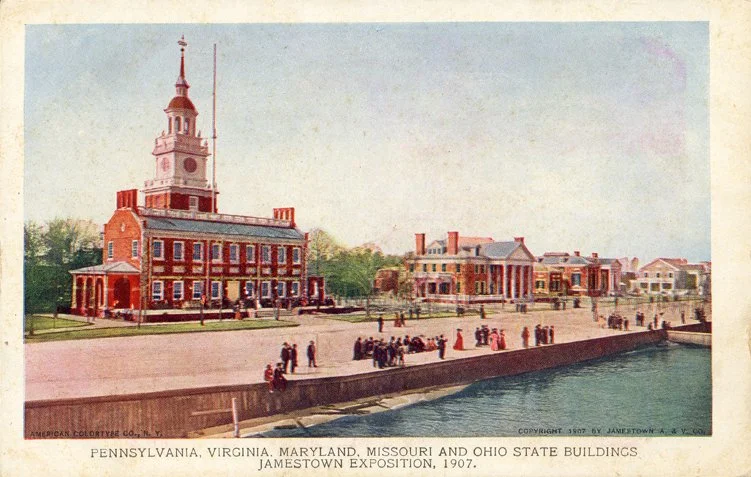

Citizens of the Hampton Roads area would quickly realize these military displays were the ones attracting the most attention, especially since many of the state buildings and the Government Pier were not completed until September.[19] Attendance dropped significantly after the opening day, and it was not until the review of the troops on Lee’s parade field that attendance picked back up. It was already being called by newspapers “one of the most attractive features of the Exposition.” The Daily Press described the parade that would occur the following Monday, May 13th, as a fantastic event with various units and foreign officials for the Jamestown Day celebration and would surely draw attention. The article indicated that this event is expected to have the highest exposition attendance after opening day.[20] Each significant spike in attendance corresponded to a significant military display or naval event. On opening day, even with the transportation issues, 44,561 admissions were reported. The other days with over 30,000 admissions reported were June 10th, June 12th, July 4th, August 15th, September 3rd, and October 25th.[21]

On June 10th, the review of the International Fleet was conducted by President Roosevelt, and another illumination of the battleships.[22] One June 12th, Virginia Day, crowds drew again for another illumination of the ships, as well as the Naval Carnival and parade of the national and state militaries under Major-General Frederick D. Grant.[23] July 4th could be reasonably expected to draw a large crowd for the patriotic nature of the holiday and the fireworks display alone. However, what made the Jamestown Exposition firework display unique from others in the area was the contributions made by the Navy through cannon salutes and the Battleship Ohio provided free minstrel entertainment for the guests.[24] August 15th was North Carolina Day and since Governor Glenn of North Carolina was arriving at the exposition in support, he brought several North Carolinian troops and provided their own demonstrations in a friendly competition with Virginia.[25] On September 3rd, the fleet stationed in the Hampton Roads area started practicing war maneuvers in preparation for their around-the-world tour in December. It would no longer be at the exposition.[26] Lastly, October 25th was designated as Greater Norfolk Day, and of course, the citizens showed their patriotism and state pride by attending the exposition. However, the event was kicked off with all troops available to parade with the Norfolk colors down the War Path, which was the primary area for amusement and the primary event of the day.[27] Each of these events drew significantly larger crowds than regular exposition operating days.

On October 25th, Representative Harry Maynard of the Second District of Virginia made it clear that if the Hampton Roads area wanted to keep the Navy there, they needed to get outside congressional support.[28] Unfortunately, tensions were still high between the Northern and Southern states, which resulted in hostilities of a Southern state being featured for an international event and a highly militarized celebration. False reports about the fair caused significant issues, especially during Ohio Day when the Ohio Representative at the exposition was forced to address the several fake reports from newspapers in his state about the exposition.[29] Although the goal of the fair was to showcase unity and the industrial progress of the United States, there were still misgivings about the choice of Hampton Roads. Therefore, in order to overcome those biases, Maynard sought to have a Congressional day established before the end of the fair to bring more outside politicians to the exposition. The plan was to showcase the tremendous military demonstrations and the grounds in person to garner support for a future appropriation effort for a naval base.[30] Based on the positive responses the exposition was getting from those who physically attended it, Norfolk citizens now transitioned to shifting opinions of the Hampton Roads area as the place to build the next naval base.

Figure 3. PA Building, Jamestown, 1907. Photograph. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:PA_Building_Jamestown_1907.jpg

Norfolk And The Navy

Before the Jamestown Exposition ended on November 30th stakeholders were already considering what to do with the site since the exposition was a financial disaster. However, the public had its own ideas and was already forming committees to advocate for a permanent naval presence. An article in the Daily Press showcases the turning point of public opinion on a military presence in Norfolk and what the Jamestown Exposition of 1907 meant to the citizens. The article states that the stakeholders intended to reopen the fairgrounds "on a strictly Coney Island basis" in an attempt to recover some of the expenses from the exposition. The newspaper responded by stating the citizens have the right to "question Mr. Martin or any other man connected with the Exposition from building up from the ruins of the Exposition a catch-penny affair."[31] While the paper acknowledges the financial situation left by the exposition, it clearly states that the public has the right to resent their plan, protest it, and protect the integrity of what the Jamestown Exposition stood for and represented for the citizens of Norfolk. A cheap fairground should not and would not occupy the same land that brought international attention and prestige to Norfolk and the Hampton Roads area. After the public backlash, the idea of a "coney-island" type of fairground was never brought up again.

Instead, several Jamestown Exposition Company board members advocated to Congress for the government to purchase the land for a new naval base as soon as the exposition ended. The Navy Department had agreed that a naval operating base needed to be built in Virginia, but there were conflicting ideas about how to proceed. Citizens of Hampton Roads, however, were convinced that there would be no better site than the old Jamestown Exposition. In 1908, the first bill was introduced to Congress, which proposed purchasing the exposition grounds for one million dollars. It was accompanied by the local committee to advocate for it in Washington, D.C. However, when faced with the decision on whether the Navy needed a new base or a new collier ship for carrying coal, the Secretary of the Navy felt it was more important to have the new collier, and the bill was left to die.[32] Instead of letting the land be purchased by another entity, T. J. Wool, the Jamestown Exposition Company board general attorney, and some of his associates purchased most of the site themselves, hoping the Navy and Congress would change their minds.[33]

The return of the Great White Fleet in 1909 showcased the shift in opinion of the citizens of Norfolk and their growing support for the Navy. A formal celebration took place after the official return of the ships, which included two "mammoth" parades on "Liberty Day," when the sailors would be able to leave their ships and participate in the festivities.[34] The formalized celebration was of such importance to the local people that even business owners made sure to put ads in newspapers to let the public know they would be closed to "welcome home the fleet and the boys in blue."[35] Newspapers also reported that all the municipal buildings, public buildings, banks, and commercial offices would be closed to support the homecoming celebration.[36] "Fleet Week," as it was called, possibly the first time this phrase was coined, was the largest celebration since The International Naval Review of 1893 in New York City prior to the opening of the Columbian Exposition in Chicago.[37] The mayor of Norfolk, Jas G. Riddick, proclaimed the return of the fleet, stating, "On behalf of the citizens of Norfolk, I extend you a hearty welcome. We all wish that you may feel that you have returned home."[38] The amount of support the city of Norfolk provided to ensure these sailors were welcomed back and allowed citizens maximum participation in the events of "Fleet Week" was a stark contrast to the "Sailors and Dogs – Keep off the grass" mentality of the previous years. Celebrating the Great White Fleet renewed the city's spirit in the fight to keep a permanent naval presence in Norfolk.

Unfortunately for the citizens of Norfolk, there would not be significant traction in the effort to secure a naval base until 1915. Due to the war in Europe, a new Naval Training Base could not wait, and the Norfolk Chamber of Commerce formed a special committee to once again advocate for a naval base in Norfolk. The committee arranged a meeting with the current Secretary of the Navy, Josephus Daniels, and, through their persistence, successfully gained his support for a naval base at Norfolk.[39] The exposition grounds were still under T. J. Wool and his partners' ownership by the Fidelity Land and Investment Corporation, which still hoped the federal government would purchase the land. Upon the United States entry into World War I on April 7th, 1917, Secretary Daniels called Wool to inquire about the land and was persuaded to introduce the motion to procure the old Jamestown Exposition grounds into the military appropriation bill.[40]

After the House rejected the proposal, citizens started advocating harder for the Senate to keep the bill alive. During the Congressional hearings regarding the decision to purchase the Jamestown Exposition site, which started on May 3rd, 1917. The Richmond Times-Dispatch published an article to persuade the procurement of the old exposition site and to persuade the stakeholders to lower their asking price for the sake of patriotism and pride for the citizens. "It would be a decided blow to Virginia if she were to lose a great training school because the owners of the property on which it was proposed to establish it demanded too great a price of the country."[41] From Representatives Kelley of Michigan and Oliver of Alabama, the primary reasons for rejecting the bill was that Yorktown or somewhere on the James River would be a more strategic location further inland and much cheaper to procure.[42]

These same issues were argued in the subcommittee of the Senate on the Naval Operating Base at Hampton Roads, as well as the cost and actual value of the land. The committee chairman for the Senate directly asked Captain McKean , a staff member for the Chief of Naval Operations, about the Yorktown option. While there are arguments that the initial prices would be cheaper, Yorktown did not have a railroad system; it was twenty miles away from the shipyard, and it was not a suitable place for a large naval base. Captain McKean even brought up the morale of the men stationed there, stating it would be an ideal location for a German prison camp but not for training sailors.[43] Norfolk had clearly demonstrated it would welcome the fleet and a naval base with open arms. Wool and his team worked for years to get this land sold to the government for the base, and he believed "their attitude is for the good of the Navy and the good of Norfolk."[44]One of the closing arguments against the procurement of the Jamestown Exposition Site had asked if the land was perfect for a fleet, why did the Fidelity Land and Investment Corporation with Mr. Wool not develop the area. Captain McKean responded that he believed it was simply the desire to have Uncle Sam located there.[45]

With the closing arguments settled, on June 15th, 1917, President Wilson signed the bill that appropriated the old Jamestown Exposition site for a naval operating base. It was purchased for $1.2 million, $800,000 less than the original offer and at a fraction of what operating the Jamestown Exposition of 1907 had cost.[46] In the end, a permanent base for the Atlantic Fleet had been achieved after a decade from the Jamestown Exposition. The dedication and advocation for the Navy to finally call Norfolk home by the citizens of Norfolk is what pushed Congress to this decision.

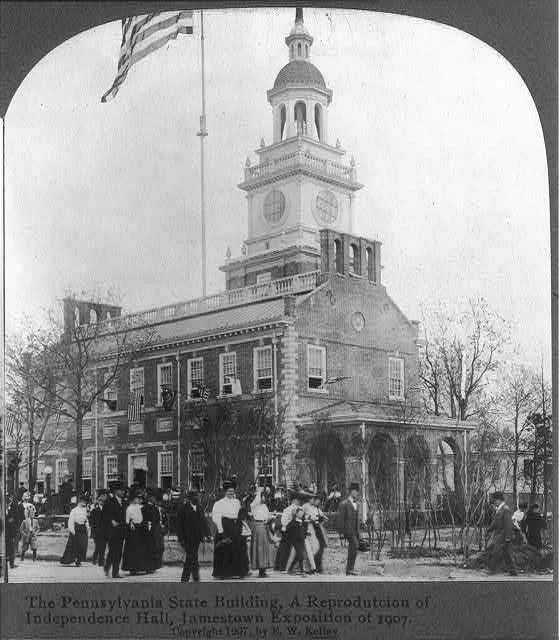

Figure 4. The Pennsylvania State Building, a Reproduction of Independence Hall, Jamestown Exposition of 1907. Photograph. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2005694822/

Conclusion

While the Jamestown Exposition of 1907 was a financial disaster, there is no argument that the event was pivotable in the influence of the citizens of Norfolk and the Hampton Roads area regarding a permanent military presence. Prior to the exposition, sailors were a begrudged consequence to Norfolk for being a port town. While the city appreciated the economic aspect of their presence in the city, the sailors were never given a warm welcome or asked to stay, nor were there any major movements to expand the shipyard over in Portsmouth. The perception of the rowdy drunken sailor persisted and permeated throughout the region. However, once Hampton Roads was thrust into the international stage with the Jamestown Exposition and the advertisement of “the grandest military and naval celebration ever attempted in any age by any nation,” the citizens were forced to make it work.[47]

During the exposition, the incredible displays by the military and the overwhelmingly positive responses caused a massive shift in public opinion. The exposition had significant flaws, such as poor opening day arrangements, massive delays with building critical structures, and poor transportation facilities for guests.[48] Despite these issues, the public still supported the exposition, especially on the days featuring major military events and displays. For the first time, the sight of a naval vessel in the Chesapeake Bay inspired awe and wonder into the citizens of Norfolk instead of dread. Once the ships left for their around-the-world display, Norfolk citizens started to form committees and advocate through their local politicians to advocate in Washington, D.C., to bring them back. Even the Jamestown Exposition Company members were trying to garner support for a government appropriation of the site before the exposition closed.

Although it took ten years to convince Congress to purchase the land for a naval base, had it not been for the persistence of the citizens of Norfolk to advocate for a base, it is likely Congress would have selected Yorktown. However, thanks to the Jamestown Exposition of 1907, which showed the United States Navy in a different light to the people citizens of Norfolk, it allowed for a shift in perception that created the desire to maintain a permanent relationship with the incredible force. From a nuisance to a blessing, the military presence at Norfolk during the Jamestown Exposition of 1907 established an international connection with Norfolk to the Navy, which the citizens came to positively advocate for to make Norfolk the official home to the Atlantic Fleet permanently.

Endnotes

2. Carroll D. Wright, E. E. Hale, Cardinal Gibbons, Edwin D. Mead, John Mitchell, Jane Addams, M. Carey Thomas, et al, “Militarism at the Jamestown Exposition,” The Advocate of Peace (1894-1920) 69, no. 2. (February 1907): 37, accessed September 23, 2024. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25752841.

3. Daily Press Editors. “To Drag Down the Exposition.” The Daily Press (Newport News, Virginia) November 19, 1907.

4. Theodore A. Curtin, "A Marriage of Convenience, Norfolk and the Navy, 1917-1967,” (MA thesis, Old Dominion University, 1969): 10, accessed August 28, 2024, https://doi.org/10.25777/s7ng-v534.

5. Curtin, “A Marriage of Convenience,” 11.

6. As citied in an interview with John L. Werheim, retired Fire Marshall, 5th Naval District, Norfolk, Va., former enlisted man, U.S Navy, 1909-12, August 20, 1965, from Curtin, Theodore.

7. The Norfolk Dispatch Editors, “What People Think of the U.S. Navy,” The Norfolk Dispatch (Norfolk, Virginia) March 2, 1903, Accessed September 24, 2024, https://virginiachronicle.com/?a=d&d=ND19030302&e=01-01-1885-01-12-1906--en-20--1--txt-txIN-Navy+sailors-------.

8. Norfolk Journal of Commerce Editors, “Explosion on the Olympia Killed One; Injured Four,” Norfolk Journal of Commerce (Norfolk, Virginia) September 15, 1903, Accessed September 24, 2024, https://virginiachronicle.com/?a=d&d=TTWVP19030915.1.1&srpos=51&e=01-01-1885-01-12-1906--en-20--41--txt-txIN-Navy+sailors-------.

9. Nicolas Veloz Goiticoa, Effect of the Jamestown Exposition on the foreign commerce of the United States and incidental remarks on the subject. Washington, D.C.: W. F. Roberts Company, 1907, Accessed September 23, 2024, https://archive.org/details/effectofjamestow00velo/page/3/mode/1up.

10. Carroll D. Wright, E. E. Hale, Cardinal Gibbons, Edwin D. Mead, John Mitchell, Jane Addams, M. Carey Thomas, et al, “Militarism at the Jamestown Exposition,” The Advocate of Peace (1894-1920) 69, no. 2, (February 1907): 35, accessed September 23, 2024, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25752841.

11. Norfolk Dispatch Editors, “Judge Lewis Speaks More Conservatively at Hampton Than His Running Mate,” Norfolk Dispatch (Norfolk, Virginia) October 12, 1905, accessed September 24, 2024, https://virginiachronicle.com/?a=d&d=ND19051012.1.1&srpos=16&e=01-01-1902-01-12-1906--en-20--1--txt-txIN-jamestown+exposition+roosevelt-------.

12. The Norfolk Landmark Editors, “To reorganize Exposition Co.” The Norfolk Landmark (Norfolk, Virginia) January 2, 1904, accessed September 28, 2024, https://virginiachronicle.com/?a=d&d=TNL19040102.1.3&srpos=1&e=02-01-1904-02-01-1904--en-20--1--txt-txIN-to+reorganize+exposition+co+-------.

13. The Norfolk Landmark Editors, “Jamestown Exposition.” The Norfolk Landmark (Norfolk, Virginia) September 13, 1903, accessed September 28, 2024, https://virginiachronicle.com/?a=d&d=TNL19030913.1.8&srpos=1&e=13-09-1903-13-09-1903--en-20--1--txt-txIN-jamestown+exposition+-------.

14. The Norfolk Landmark Editors, “To reorganize Exposition Co.”

15. Jamestown Tercentennial Exposition, The Tidewater Cities of Hampton Roads, Virginia, your hosts for 1907, 1607-1907, the Jamestown Exposition. St. Louis, MO: Con P. Curran Publishers, 1907, accessed September 26, 2024, https://archive.org/details/tidewatercitieso01jame/page/3/mode/1up?view=theater.

16. Richmond Evening Journal Editors, “Blue Skies Smile Upon Jamestown Expo.,” Richmond Evening Journal (Richmond, Virginia) April 26, 1907, accessed September 26, 2024, https://virginiachronicle.com/?a=d&d=TEJ19070426.1.1&srpos=3&e=20-04-1907-01-12-1907--en-20--1--txt-txIN-jamestown+exposition+-------.

17. Jamestown Tercentennial Exposition, The Tidewater Cities of Hampton Roads, 31.

18. Keiley, The Official Blue Book, 649.

19. Charles Russel Keiley, ed. The Official Blue Book of the Jamestown Ter-Centennial Exposition. Norfolk, VA: The Colonial Publishing Company, 1907, 151, accessed September 26, 2024, https://books.google.com/books?id=Dk47AQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false.

20. Daily Press Editors. “Large Crowd on the Exposition Grounds.” Daily Press (Newport News, Virginia) May 11, 1907, accessed September 28, 2024, https://virginiachronicle.com/?a=d&d=DP19070511.1.3&srpos=1&e=11-05-1907-11-05-1907--en-20--1--txt-txIN-large+crowd+on-------.

21. Keiley, The Official Blue Book, 700-703.

22. The Norfolk Landmark Editors, “Review of the Great International Fleet,” The Norfolk Landmark (Norfolk, Virginia) June 9, 1907, accessed September 26, 2024, https://virginiachronicle.com/?a=d&d=TNL19070609.1.11&srpos=1&e=09-06-1907-10-06-1907--en-20--1--txt-txIN-jamestown+exposition+-------.

23. The News Leader Editors, “Jamestown Exposition Program for ‘Virginia Day’,” The News Leader (Richmond, Virginia) June 11, 1907, accessed September 26, 2024, https://virginiachronicle.com/?a=d&d=NEL19070611.1.1&srpos=3&e=11-06-1907-13-06-1907--en-20--1--txt-txIN-jamestown+exposition+-------.

24. The Times Dispatch Editors, Patriotism Rules Jamestown To-day,” The Times Dispatch (Richmond, Virginia) July 4, 1907, accessed September 26, 2024, https://virginiachronicle.com/?a=d&d=TD19070704.1.4&e=03-07-1907-05-07-1907--en-20--21--txt-txIN-jamestown+exposition+-------.

25. Daily Press Editors, “Today’s Exposition Program,” Daily Press (Newport News, Virginia) August 15, 1907, accessed September 26, 2024, https://virginiachronicle.com/?a=d&d=DP19070815.1.1&srpos=9&e=15-08-1907-15-08-1907--en-20--1--txt-txIN-jamestown+exposition+-------.

26. Norfolk Journal of Commerce Editors, “North Atlantic Fleet Now off Exposition,” Norfolk Journal of Commerce (Norfolk, Virginia) September 3, 1907, accessed September 26, 2024, https://virginiachronicle.com/?a=d&d=NJCTWVP19070903.1.1&e=02-09-1907-03-09-1907--en-20--1--txt-txIN-jamestown+exposition+-------.

27. The Norfolk Landmark Editors, “Program for Greater Norfolk Day at Exposition,” The Norfolk Landmark (Norfolk, Virginia) October 25, 1097, accessed September 26, 2024, https://virginiachronicle.com/?a=d&d=TNL19071025.1.1&e=25-10-1907-25-10-1907--en-20--1--txt-txIN-jamestown+exposition+-------.

28. The News Leader Editors, “New Plan to Aid Big Fair,” The News Leader (Richmond, Virginia) October 25, 1907, accessed September 27, 2024, https://virginiachronicle.com/?a=d&d=NEL19071025.1.1&e=25-10-1907-25-10-1907--en-20--1--txt-txIN-jamestown+exposition+-------.

29. The Norfolk Landmark Editors, “Commissioners Defend Fair,” The Norfolk Landmark (Norfolk, Virginia) July 4, 1907, accessed September 28, 2024, https://virginiachronicle.com/?a=d&d=TNL19070704.1.4&srpos=8&e=03-07-1907-05-07-1907--en-20--1--txt-txIN-jamestown+exposition+-------.

30. The News Leader Editors, “New Plan to Aid Big Fair.”

31. Daily Press Editors, “To Drag Down the Exposition.” The Daily Press (Newport News, Virginia) November 19, 1907, accessed September 28, 2024, https://virginiachronicle.com/?a=d&d=DP19071119.1.4&srpos=1&e=19-11-1907-19-11-1907--en-20--1--txt-txIN-to+drag+down+the+exposition+-------.

32. W. H. T. Squires, "Norfolk in Bygone Days", Norfolk Ledger Dispatch, November 11, 1937, citing personal reminiscence of T. J. Wool, (scrapbook at Kirn Memorial Library, Norfolk), Vol. I, p. 146, as cited by from Theodore A. Curtin, "A Marriage of Convenience, Norfolk and the Navy, 1917-1967,” Master of Arts (MA), Thesis, History, Old Dominion University, 1969, p. 13, accessed September 23, 2024, https://doi.org/10.25777/s7ng-v534.

33. W. H. T. Squires, “Norfolk and The Navy,” Know Norfolk, Virginia, (publication of the Norfolk Advertising Board), VI, No. 2 (August, 1944), p. 60, as cited by from Theodore A.

34. The Norfolk Landmark Editors, “Great Crowds Will Welcome Battle Fleet,” The Norfolk Landmark (Norfolk, Virginia) February 21, 1909, accessed September 25, 2024, https://virginiachronicle.com/?a=d&d=TNL19090221.1.3&srpos=1&e=01-02-1909-01-03-1909--en-20--1--txt-txIN-Fleet+return-------.

35. Daily Press Editors, “Page Four Advertisements”, Daily Press (Newport News, Virginia) February 21, 1909, accessed September 25, 2024, https://virginiachronicle.com/?a=d&d=DP19090221.1.4&srpos=5&e=01-02-1909-01-03-1909--en-20--1--txt-txIN-Fleet+return-------.

36. Virginia-Pilot Editors, “Merchants Will Give Employes Holiday,” Virginia-Pilot (Norfolk, Virginia) February 21, 1902, accessed September 25, 2024, https://www.newspapers.com/image/844571388/?match=1&terms=Fleet%20return.

37. The News Leader Editors, “Crowds Still Linger to See Battleship Fleet,” The News Leader (Richmond, Virginia) February 23, 1909, accessed September 25, 2024, https://virginiachronicle.com/?a=d&d=NEL19090223.1.1&srpos=14&e=01-02-1909-01-03-1909--en-20--1--txt-txIN-Fleet+return-------.

38. Virginia-Pilot Editors, “Norfolk and Portsmouth Greet Men of Fleet,” Virginia-Pilot, February 23, 1909, accessed September 25, 2024, https://www.newspapers.com/image/844571627/?match=1&terms=fleet%20return%20mayor.

39. Norfolk Chamber of Commerce, Minutes of Board of Directors Meeting, September 3, 1915, as cited by Theodore A. Curtin, "A Marriage of Convenience, Norfolk and the Navy, 1917-1967,” Master of Arts (MA), Thesis, History, Old Dominion University, 1969, p. 2, accessed September 23, 2024. https://doi.org/10.25777/s7ng-v534.

40. William Foss, The United States Navy in Hampton Roads, (Norfolk, Virginia: The Donning Company, 1984), 66, accessed August 28, 2024, https://archive.org/details/unitedstatesnavy0000foss/page/n5/mode/1up?q=jamestown+exposition

41. Richmond Times-Dispatch Editors, “Naval Training School Site,” Richmond Times-Dispatch (Richmond, Virginia) May 5, 1917, accessed September 28, 2024, https://virginiachronicle.com/?a=d&d=RTD19170505.1.6&srpos=1&e=05-05-1917-05-05-1917--en-20--1--txt-txIN-Naval+training+school+site-------.

42. Alexandria Gazette Editors, “No Base at Jamestown,” Alexandria Gazette (Alexandria, Virginia) June 8, 1917, accessed September 28, 2024, https://virginiachronicle.com/?a=d&d=AG19170608.1.3&srpos=1&e=06-06-1917-08-06-1917--en-20--1--txt-txIN-no+base+at+Jamestown-------.

43. United States Navy Department, “Jamestown Exposition property and other property for the naval base at Hampton Roads, Virginia,” Washington: Government Printing Office, 1917, page 19, accessed September 25, 2024, https://www.loc.gov/item/17026539/.

44. United States Navy Department, “Jamestown Exposition,” 11.

45. United States Navy Department, “Jamestown Exposition,” 19.

46. Foss, The United States Navy, 66.

47. Carroll et al, “Militarism at the Jamestown Exposition”, 35.

48. Keiley, The Official Blue Book, 733.

Amanda Collier

Amanda Collier calls the small town of Newport, North Carolina, home, where Marine Corps Air Station Cherry Point and the Naval Junior Reserve Officers Training Corps unit at West Carteret High School sparked her lifelong fascination with the military. She enlisted in the Navy the moment she graduated high school and eventually commissioned as an Information Professional Officer. She is currently stationed at Naval Station Norfolk.

She’s married to an incredible Navy Chief Warrant Officer, Chad, who has cheered on every academic adventure she’s taken. Amanda is also a devoted animal-rescue advocate and proudly serves as staff to four outrageously spoiled cats who graciously allow them to live in their house.

When she’s not on duty, Amanda loves photography, cooking, reading, and traveling. She lives by the words of her lifelong hero, Steve Irwin, “Be passionate and enthusiastic in the direction that you choose in life, and you'll be a winner.”