Booker T. Washington: A Strategist, Not an Apologist

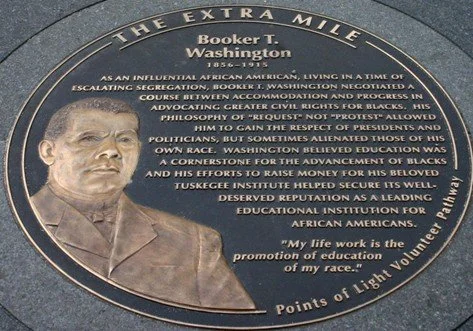

After visiting Booker T. Washington’s school in Tuskegee, Alabama in 1908, Len G. Broughton wrote, “Perhaps no man in this country is better known than Booker T. Washington, and perhaps no man is more poorly understood or incorrectly reported as he.”[1] This assessment remains true today, as historians often misrepresent Washington and his accomplishments. Many historians examine Washington in contrast to his contemporary, W. E. B. DuBois, an educated northerner born into freedom. DuBois strove for political and social equality, and he was a founding member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). While DuBois fought for political equality, Washington’s experiences with slavery and freedom solidified in his mind the economic value of skilled labor and the importance of economic independence for the race. Because Washington focused on education in industrial trades as the primary means of enfranchising the black population, many modern scholars, with the benefit of a rather equal society, judge Washington’s action as too accommodating to the inequalities of his time. Following Reconstruction in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, state and local legislatures enacted racial discrimination laws, known colloquially as Jim Crow laws, to minimize the effects of emancipation and salvage a racial hierarchy. Many see Washington as an apologist for the oppression created by legal racial discrimination and voter suppression laws of the Jim Crow era. Despite this judgment, Washington was not an apologist, but a strategist in his rhetoric, his philosophy, and his public appeal.

Partly due to his experiences in his early life, Washington’s rhetoric, influence with powerful people, method of education, and unity with other leaders were strategic, and they garnered a positive reception from both black and white audiences. Anecdotes from his autobiography, Up from Slavery, reveal the origins of Washington’s belief in the power of industrial education to enfranchise members of society. He echoed this belief in his public speeches, strategically presenting his philosophy of education to different audiences. As a result of this rhetoric, Washington maintained close relationships with such influential people as steel baron and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie and President Theodore Roosevelt, and he used these relationships to increase the station of black Americans. He also carried out his philosophy in the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial School, which emphasized education in industrial trades. Finally, Washington worked to maintain the public image of black leaders, even when they had internal disagreements. All of these actions served to accomplish Washington’s goal of uplifting black Americans, and they met a largely positive reception among all contemporary audiences.

Modern historians misunderstand Washington if they view him through the framework of modern society rather than considering his historical context. They compare him to more radical leaders like DuBois and discount his subtler, more measured strategies. With the benefit of knowing the outcome of the Reconstruction era, modern historians discredit Washington for devoting his life to industrial education rather than higher academic pursuits or political power. Perhaps because Washington focused on uplifting and enfranchising the black population rather than making them politically equal to white Americans, modern historians often view him as an apologist rather than a strategic leader. In this way, historians miss important historical context and fail to view Washington as a dynamic, multi-dimensional figure.

In The Education of Blacks in the South, 1860-1935, James D. Anderson overviews black education from the Reconstruction era to the thirties, and he presents Washington’s Tuskegee school as a step backward in this journey. Anderson contrasts Washington’s education initiative to the earlier “native schools” that black communities established shortly after slavery and that Washington himself taught and attended.[2] Washington’s school and the Hampton Institute, Anderson suggests, compromised black Americans’ aspirations for education by reducing their learning to industrial pursuits and skilled labor.[3] Because of Tuskegee’s and Hampton’s emphasis on industrial education and economic freedom over political equality, Anderson characterizes these schools as extensions of the oppression under slavery.[4] In this way, Anderson only measures Tuskegee’s success based on its ability to politically equalize black and white Americans, though this was not Washington’s goal. Therefore, he fails to see Washington’s strategy in leveraging the South’s economic interest. Because of his one-sided approach, Anderson misunderstands Washington’s goal for black Southerners’ economic freedom.

Houston A. Baker also takes Washington’s actions out of their historical context in Turning South Again: Re-Thinking Modernism/Re-Reading Booker T. Baker analyzes Washington’s actions through a modernist psychological lens, reading into the anecdotes in his autobiography to explain his thoughts and actions. In a pseudo-scientific and pseudo-historical sequence, Baker diagnoses Washington with anxiety-driven panic attacks using the DSM-IV psychological manual.[5] Further, he uses Freudian methods to draw conclusions about Washington’s personality based on his relationship with his mother and father.[6] He concludes that Washington sought to “perform” as a white man because of his absent white father.[7] The implication is that Washington’s thought life informed his political ideology which was not as radical as some of his peers, making him an apologist for racial hierarchy. These assessments can neither pass as true psychological assessments nor historical ones. Baker attempts to view Washington through an expressly modernist framework and neglects to consider Washington’s historical context.

Michael B. Boston takes a much more positive view of Washington, though with a purely economic perspective. In The Business Strategy of Booker T. Washington, Boston purposefully surveys the historical context and personal background that informed Washington’s entrepreneurial philosophy. This approach focused on uplifting the entire race rather than uplifting individuals, taking economic opportunities in one’s own community, and doing business in a variety of markets.[8] His industrial education program at Tuskegee was the manifestation of his entrepreneurial philosophy, and it brought black Americans closer to economic self-sufficiency.[9] By identifying the essence of Washington’s economic philosophy, Boston avoids Anderson’s and Baker’s folly: reading Washington with a modern, political perspective.

Knowing that Washington’s strategy was more economic than political, it is evident that historians who criticize his lack of political uplift misunderstand Washington’s aims. Historians like Boston examine the historical context and view Washington’s intentions as he expressed them, but views of Washington as an apologist still prevail. The sources show that Washington’s rhetoric, influence, educational methods, and public unity with other black leaders were strategic and resulted in a positive reception from black and white audiences.

To understand Washington in his context and full resolution, it is necessary to examine the experiences in his early life that shaped his philosophy. His passion for education developed as soon as his earliest memories, and this catalyzed his devotion to the Tuskegee Institute. In his autobiography, Up from Slavery, Washington recounted that as an enslaved boy, he thought “to get into a schoolhouse and study in this way would be about the same as getting into paradise.”[10] He added that the earliest thoughts he remembered having were of “an intense longing to learn to read.”[11] From the time that he was freed by the Emancipation Proclamation, Washington overcame immense obstacles in the way of his education. As a newly freed boy, he worked long hours in a salt mine and elected to attend school with the few remaining waking hours in his day.[12] When he learned all that his community’s teachers could offer, Washington set his mind on attending the Hampton Institute without knowing exactly where it was, how to get there, or what it would cost.[13] To that end, he saved up for over a year to go to Hampton but found his travel expenses to deplete the funds before he reached the school.[14] To pay for his trip and his tuition, he worked at a shipyard and then as the janitor at Hampton.[15] His autobiography conveys that hard work and an insatiable passion for education marked every step along Washington’s path to education, shaping his view that industrial skills had immense economic value.

Also evidenced throughout Washington’s anecdotes are his meek views of slavery and race relations, which informed his strategy as a black leader. He defined slavery as a system that gripped the nation and victimized its inhabitants—both black and white. He did not find fault in his absent white father or his mother when she stole food for her family, for they were each victims of “the institution which the Nation unhappily had engrafted upon it at that time.”[16] He also spoke of slavery’s oppression as if it were entirely left in the past. Additionally, he repeated many times that he held no bitterness toward white Americans, even former slaveholders and Confederate soldiers.[17] In fact, he recounted how newly freed men would maintain relationships with and obligations to their former masters “as a result of their [former slaves’] kindly and generous nature,” while he maintained that slavery was “miserable, desolate, and discouraging.”[18] This meek, principled outlook on race relations informed Washington’s subtle, respectful tone but stains his record in the eyes of modern scholars like Anderson and Baker, who would rather he reacted differently to his own enslavement.

While his early struggles seeded his passion for education and his experience with slavery shaped his views of race relations, still other experiences formed Washington’s industrial education model. First, he observed that after emancipation, former slaves were equipped with practical skills like cooking and agriculture, while former slaveholders were left without the skills to maintain their households.[19] Thus, Washington saw the economic value of specialized labor, though he acknowledged that slavery gave labor a negative stigma.[20] Washington made his point of view manifest when he worked to pay for his education at the Hampton Institute: “I was determined from the first to make my work as janitor so valuable that my services would be indispensable.”[21] His strategy succeeded, as Hampton allowed him to return each semester despite his debts.[22] Washington’s experiences surrounding the value of skilled labor shaped his passion for industrial education and his philosophy that education itself could not eliminate the need for manual labor, but specialized labor would maintain one’s economic value.[23]

Washington’s philosophy for black uplift was to train students to be economically valuable, and he sold this vision to diverse audiences in his public addresses. He expressed his economic outlook with moving rhetoric in his speech at the Atlanta Exposition and his 1898 Lincoln Day address. The former, delivered in 1895, contains his famous quotation, “cast down your bucket where you are,” calling black Americans to use their skills in industrial trades to participate in the economy and improve their economic status.[24] With the striking example of a boat’s crew dying of thirst, Washington conveyed the irony of a population possessing skills for labor suffering economically because they strive to escape the necessity of labor. With the same impact, he turned the illustration to target the white audience, imploring them to cast their buckets by hiring the skilled workers found in black communities.[25] In his 1898 speech at the Armstrong Foundation’s Lincoln Day celebration, Washington used another striking metaphor to express his philosophy. Fitting the occasion, he used Lincoln’s quotation, “a new birth of freedom,” from the Gettysburg Address to represent black Americans’ economic freedom in addition to their political freedom.[26] With this illustration, he inculcated the importance of industrial education for his audience: it served as the ticket to a second freedom for black Americans. These two powerful metaphors exemplify how Washington masterfully used rhetoric to convey his philosophy and convince others of it.

Another part of Washington’s rhetorical strategy was fostering cooperation with his white audiences. He asserted that the black American “cannot afford to act in a manner that will alienate his Southern white neighbors from him.”[27] Perhaps for this reason, he took a respectful tone when addressing white audiences, and he attempted to convince them of the benefit that black education could have for them rather than demanding their compliance on moral grounds. In his speech at the 1898 Jubilee Thanksgiving service, Washington listed the occasions in American history when slaves and freedmen graciously aided their white counterparts: the Revolutionary War, the Battle of New Orleans, the Civil War, and the Spanish-American War.[28] He punctuated this list with the sympathetic statement, “decide for yourselves whether a race that is thus willing to die for its country, should not be given the highest opportunity to live for its country.”[29] With such influential men as President McKinley and his cabinet in attendance, Washington delivered this strategic plea for understanding and sympathy.

With a similarly effective rhetorical strategy, Washington sold the benefits of black education to white audiences. After accepting an honorary Master of Arts degree from Harvard University, Washington used a humble tone and evoked images of Biblical morality to convince his audience of black education’s value: “In the economy of God there is but one standard by which an individual can succeed.”[30] He went on to speak as a representative of black Southerners and describe the “American standard” by which all Americans, black and white, are judged, explaining that injustice and ignorance among one race reflects poorly on all: “There is no escape—man drags man down, or man lifts man up.”[31] Washington repeated this appeal to American honor in his 1904 Lincoln Day address.[32] Invoking a logical strategy, Washington gave statistics about the success of educated black Southerners and asserted that universal education was good for a nation’s industry, using South Africa as a negative example of a society whose industries “refuse to prosper for lack of labor” since its young people were not educated.[33] In both of these addresses, Washington used compelling metaphors to convince white audiences that black education was beneficial to America and, in turn, to the white race. With a common-sense philosophy expressed through compelling rhetorical devices, Washington won over white and mixed audiences to gain support for his education program.

The rhetorical strategies that Washington employed to communicate his philosophy won the attention and respect of powerful people, increasing Washington’s influence. Andrew Carnegie seems to have digested and believed Washington’s argument that universal education would uplift all Americans because he repeated this sentiment in his address at the Tuskegee Institute’s twenty-fifth anniversary.[34] In this address, Carnegie bought into Washington’s ideas of racial cooperation and the value of education: “Human society is one great whole and the degradation of one part lowers the lives of the other.”[35] As a New Yorker, Carnegie applied this sentiment to European immigrants’ education.[36] That such an influential man wholeheartedly backed Washington’s program demonstrates the success of his rhetoric and his meaningful education program.

Washington also had influence with President Theodore Roosevelt, who looked to him for appointment recommendations. Correspondence between Secretary of the Interior Ethan Allen Hitchcock and President Roosevelt shows that the President passed on Washington’s recommendation for the office of Receivership of Public Moneys, a black man named Mr. Bush.[37] Evidently, Hitchcock declined to appoint Mr. Bush because, in a second letter sent a month later, Roosevelt asked Hitchcock to choose from three more of Washington’s recommendations.[38] One of the recommendations Washington identified as a “merchant and planter,” and another was a “carpenter and contractor,” showing the value that Washington placed on manual labor.[39] That Roosevelt deferred to Washington’s recommendation of black professionals shows his respect for Washington, and this anecdote combats the notion that Washington did not aspire for black Americans to hold public offices.

Washington’s economic philosophy was realized at the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute. Washington’s 19th annual report of the school clearly stated the reasons for industrial education.[40] Combating the claim that few students go on to work in the trade in which they trained, Washington retorted, “the chief value of industrial education is to give the students habits of industry, thrift, economy and an idea of the dignity of labor.”[41] This sentiment aligns with Washington’s rhetoric on the value of labor. For these reasons, the Tuskegee Institute generally educated students in industrial trades, in contrast to mainstream white education.

The Tuskegee Institute’s industrial education included instruction in several trades that fulfilled the school’s maintenance needs. Washington described the beginnings of the industrial programs: “One of the first things we needed was food, and so we began raising it on the school farm. Then we needed buildings, so we introduced carpentry…As the school grew larger new wants arose, and, in every case, as soon as we were able to do so we set the students to work to supply them.”[42] These industries grew to include machining, shoemaking, tailoring, blacksmithing, agriculture, nursing, and medicine, among others.[43] Regardless of their trade, students spent half of their learning time in the classroom and the other half doing some specialized labor.[44] This amounted to ten hours of work and ten hours of class, split between two days.[45] Other than their industrial education, students received moral and behavioral instruction, partly through Sunday evening speeches by Washington, their principal.[46] Washington described the purpose of these addresses: “to speak straight to the hearts of our students and teachers and visitors concerning the problems and questions that confront them in their daily life in the South.”[47] Topics ranged from encouragement and honesty to word choice, personal finance, and appearance.[48]

Practical instruction, productive labor, and work ethic characterized the education at the Tuskegee Institute, and these features align with Washington’s belief in the importance of specialized labor for black uplift. Not only this, but the Tuskegee school also successfully realized Washington’s vision for black economic success. After visiting the school, Broughton observed that the black students, and black people in general, were both capable and ambitious, picking up every trade and often suffering hardships to gain that training.[49] Not only did Tuskegee graduates find employment with ease, but they also threatened white workers in skilled trades.[50] Broughton’s assessment and the success of Tuskegee graduates show that Washington’s industrial education model was successful, revealing his genius and strategy and negating the notion that his actions were too moderate or apologetic.

As part of his strategy, Washington worked to maintain a unified public image among black leaders despite their disagreements. In his correspondence with W. E. B. DuBois and other black leaders with whom he disagreed, Washington was cordial and expressed a spirit of unity.[51] In contrast, in preparation for a meeting with other black leaders, DuBois issued a memorandum to those attendees he classified as “anti-Washington” with plans to challenge Washington’s views at the meeting.[52] After classifying himself and four other men as “Uncompromisingly Anti-Washington,” DuBois identified the tactics of pro-Washington men, including “conciliation and compromise,” and urged the men on his side to “bring every speech or letter or record of Washington you can lay hands on so that he can face [sic] his record in print.”[53] Additionally, he arranged for the anti-Washington men to meet separately.[54] Whereas DuBois spent his energy arranging opposition to Washington, Washington made every effort to reconcile black leaders and maintain a unified voice.

A letter from Washington to DuBois illustrates the former’s efforts to unite the race’s leaders. Washington urged DuBois to meet with journalist Timothy Thomas Fortune, though they disagreed, stating that a meeting comprised of men of different schools of thought “shall in every way represent all the interests of the race.”[55] In another correspondence, Washington acted as an intermediary between Republican partyman Charles William Anderson and Colored American Magazine editor Fred R. Moore.[56] Washington urged Anderson to drop his disagreement with Moore, not only because his efforts “could otherwise be devoted to higher ends,” but also because the men’s bickering drew the attention and disappointment of onlookers at a recent event.[57] Washington was prudently aware of how this behavior reflected on Anderson’s image as a black public servant. It is evident that Washington sought to maintain unity among black activists out of an earnest desire to fully represent the diverse interests of the race with one voice and to strengthen the race’s public image.

Washington’s rhetoric and economic strategy had a captivating effect on white audiences, who saw him as the foremost man of his race at the time. With great enthusiasm, reporter James Creelman described Washington’s speech at the 1895 Atlanta Exposition, including an appreciation letter from President Grover Cleveland, representing white audiences’ warm reception of Washington.[58] Creelman posited that Washington’s famous speech “marks a new epoch in the history of the South,” highlighting that Washington spoke of separate social spheres but a unified vision of mutual progress.[59] By all accounts, the speech was articulate and galvanizing to its mixed audience, and “it is the first time that a Negro has made a speech in the South on any important occasion before an audience composed of white men and women.”[60] Creelman’s account unwaveringly lauded Washington’s presence and rhetorical effect, and he recalled the audience’s utter captivation with the address.[61] This glowing account speaks to the success of Washington’s rhetoric and the message behind it.

Not only did white audiences respond to Washington’s orations, but they also sought to replicate Washington’s educational model in white schools. One author argued for white schools to adopt industrial education, echoing Washington’s observations that the South needed industrial labor and that white Southerners were untrained in this area.[62] Like Washington, journalist Richard H. Edmonds argued that skilled labor was undervalued among educators, calling it the South’s most valuable raw material.[63] Similarly, Broughton left Tuskegee with the sense that industrial education for black Southerners was far more advanced than that for white Southerners: “For the industrial training of the white people of the South there is not one-fourth of the money spent on equipment, and there is not one-fourth of the amount of ambition to be trained.”[64] Both of these authors found something enviable in the Tuskegee method and felt it so successful that they advocated for young white Southerners to have the same educational opportunities as black Southerners did. That the Tuskegee Institute galvanized white audiences to duplicate its methods and opportunities disproves Anderson’s claim that Washington’s attempt at black education had failed.

Despite some historians’ judgments that he was a moderate white apologist, Washington was both strategic and nuanced in his plan for black uplift. His rhetoric moved white audiences with powerful imagery, gained their sympathy and respect, and presented logical arguments for black education. While his powerful oration did help to sell his educational model, it was the successful application of his philosophy at the Tuskegee school that ultimately proved its soundness and sensibility. Students of Tuskegee worked hard to master industrial skills and made themselves economically valuable to the markets of the industrializing South. The Tuskegee Institute embodied Washington’s emphasis on the value of skilled labor, and it drew positive responses—and envy—from white Southerners. He worked to maintain this positive image by making every effort to unify black leaders and represent each of their interests. These are the actions that made Washington the foremost man of his race and gave him influence with multiple U.S. Presidents. Washington ultimately advanced the station of black Americans with incredible success.

Washington’s philosophy was based on his experiences, and his strategy served to further his goals for black economic freedom. But because he focused on the value of labor and did not advocate for political or social equality on their principles, some modern historians demonize Washington, viewing his ideas and actions through a modern lens that demands political and social equality, and his legacy remains controversial because his policies were not as radical as his contemporaries’ or his successors’. Anderson finds Washington’s view of labor as an extension of slavery and measures his school’s success by its similarity to white schools. However, contemporary sources show that white Southerners envied the Tuskegee model, which was extremely well-received and successful for black economic uplift. Baker attempts to assess Washington using modern psychology, removing him from the context of the Reconstruction era South, though its economy and politics largely informed Washington’s conclusions. Boston does not criticize Washington in this way, but he assesses him from a purely economic standpoint, neglecting the moral philosophy and social strategy that also contributed to Washington’s actions. Despite these accounts, the sources show Washington’s experience-based philosophy, its rhetorical appeal, and its strategic application to the Tuskegee Institute.

End Notes:

[1] Len G. Broughton, Tuskegee Visit Was His Topic: Dr. Len. G. Broughton Describes Conditions at Booker T. Washington’s School (Alabama: Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute Print, 1908), 4, https://regent.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01REGENT_INST/4p5on9/cdi_hathitrust_hathifiles_osu_32435011613940.

[2] James D. Anderson, The Education of Blacks in the South, 1860-1935 (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1988), 7, https://go.exlibris.link/2YpdScrJ.

[3] Anderson, The Education of Blacks, 80.

[4] Anderson, The Education of Blacks, 44.

[5] Houston A. Baker, Turning South Again: Re-Thinking Modernism/Re-Reading Booker T., E-Duke Books Scholarly Collection (Durham, NC: Duke University Press Books, 2001), 39, https://go.exlibris.link/q05bxJwS.

[6] Baker, Turning South Again, 55, 70.

[7] Baker, Turning South Again, 55-56.

[8] Michael B. Boston, The Business Strategy of Booker T. Washington: Its Development and Implementation (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2010), 57-61.

[9] Boston, The Business Strategy, 71.

[10] Booker T. Washington, Up from Slavery (Oviedo, Spain: King Solomon, 2021), 12.

[11] Washington, Up from Slavery, 19.

[12] Washington, Up from Slavery, 20-21.

[13] Washington, Up from Slavery, 25.

[14] End Notes: Washington, Up from Slavery, 26-27.

[15] Washington, Up from Slavery, 27-29.

[16] Washington, Up from Slavery, 10-11.

[17] Washington, Up from Slavery, 13.

[18] Washington, Up from Slavery, 14, 10.

[19] Washington, Up from Slavery, 15.

[20] Washington, Up from Slavery, 15.

[21] Washington, Up from Slavery, 30.

[22] Washington, Up from Slavery, 36.

[23] Washington, Up from Slavery, 39.

[24] Booker T. Washington, Speech at Atlanta Exposition, September 18, 1895, African American Odyssey Collection, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, 2, https://www.loc.gov/static/classroom-materials/naacp-a-century-in-the-fight-for-freedom/documents/speech.pdf.

[25] Washington, Speech at Atlanta Exposition, 3.

[26] Booker T. Washington, Lincoln Day Address Delivered to the Armstrong Association, February 12, 1898, Daniel Murray Pamphlet Collection, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, 3, https://www.loc.gov/item/91898140/.

[27] Washington, Up from Slavery, 41.

[28] Booker T. Washington, Address Delivered at the Jubilee Thanksgiving Services, 1898, Daniel Murray Pamphlet Collection, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, 4-5, https://www.loc.gov/item/91898139/.

[29] Washington, Address delivered at the Jubilee Thanksgiving services, 5-6.

[30] Booker T. Washington, Address Delivered at the Alumni Dinner of Harvard University, June 24, 1896, Daniel Murray Pamphlet Collection, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, 4, https://www.loc.gov/resource/lcrbmrp.t0f13/?st=gallery.

[31] Washington, Address delivered at the alumni dinner of Harvard University, 4.

[32] Booker T. Washington, “Negro Education Not a Failure,” Lincoln Day address at Madison Square Garden, February 12, 1904, African American Pamphlet Collection, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, https://www.loc.gov/item/92838848/.

[33] Washington, “Negro Education Not a Failure,” 5-6.

[34] Andrew Carnegie, “The Education of the Negro: A National Interest,” April 5, 1906, Address at 25th Anniversary Celebration of the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute, African American Pamphlet Collection, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, https://www.loc.gov/resource/rbaapc.04200/?sp=1.

[35] Carnegie, “The Education of the Negro,” 3.

[36] Carnegie, “The Education of the Negro,” 5.

[37] George B. Cortelyou to E. A. Hitchcock, February 17, 1902, Papers of Ethan Allen Hitchcock, Communications with the Executive Department, 1900-1907, National Archives, https://catalog.archives.gov/id/7268938.

[38] Theodore Roosevelt to E. A. Hitchcock, March 21, 1902, Papers of Ethan Allen Hitchcock, Communications with the Executive Department, 1900-1907, National Archives, https://catalog.archives.gov/id/7268954.

[39] Roosevelt to E. A. Hitchcock.

[40] Booker T. Washington, “Nineteenth Annual Report of the Principal of the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute,” 1900, Daniel Murray Pamphlet Collection, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, https://www.loc.gov/resource/lcrbmrp.t1704/?st=gallery.

[41] Washington, “Nineteenth Annual Report,” 4.

[42] Booker T. Washington, “Training Colored Nurses at Tuskegee,” The American Journal of Nursing 114, no. 2 (2014): 22–23. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000443768.27635.c6.

[43] Broughton, Tuskegee Visit, 7-8; Washington, “Training Colored Nurses,” 22-23.

[44] Washington, “Training Colored Nurses,” 22.

[45] Broughton, Tuskegee Visit, 10.

[46] Booker T. Washington, Character Building: Being Addresses Delivered on Sunday Evenings to the Students of Tuskegee Institute (New York: Doubleday Page & Company, 1902), https://archive.org/details/characterbuildin00wash/page/n9/mode/2up.

[47] Washington, Character Building, preface.

[48] Washington, Character Building, 51, 63, 133, 245, 267.

[49] Broughton, Tuskegee Visit, 12.

[50] Broughton, Tuskegee Visit, 13.

[51] Booker T. Washington, W. E. B. DuBois, Joanna P. Moore, Dana Ferrin, Kittredge Wheeler, and J. W. Cooper, W. E. B. DuBois Papers, Series 1A: General Correspondence, 1877-1965, University of Massachusetts, Amherst. https://credo.library.umass.edu/view/series/mums312-s01.

[52] W. E. B. DuBois, “Memoranda on the Washington Meeting,” 1903, W. E. B. DuBois Papers, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA, https://credo.library.umass.edu/view/full/mums312-b006-i306.

[53] DuBois, “Memoranda.”

[54] DuBois, “Memoranda.”

[55] Booker T. Washington, Letter to W. E. B. DuBois, February 12, 1903, W. E. B. DuBois Papers, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA, https://credo.library.umass.edu/view/full/mums312-b006-i110.

[56] Booker T. Washington, “To Charles William Anderson,” in Booker T. Washington Papers, ed. Nan Elizabeth Woodruff, Geraldine McTigue, Raymond Smock, and Louis R. Harlan, vol. 10 (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1981), https://regent.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01REGENT_INST/lp6iog/alma991013103888907516.

[57] Washington, “To Charles William Anderson,” 315.

[58] James Creelman, “The Effect of Booker T. Washington’s Atlanta Speech,” 1895, Daniel Murray Pamphlet Collection, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, https://www.loc.gov/item/91898527/.

[59] Creelman, “The Effect of Booker T. Washington’s Atlanta Speech.”

[60] Creelman, “The Effect of Booker T. Washington’s Atlanta Speech.”

[61] Creelman, “The Effect of Booker T. Washington’s Atlanta Speech.”

[62] Richard H. Edmonds, “The South's Industrial Task: A Plea for Technical Training of Poor White Boys,” Address before the Annual Convention of the Southern Cotton Spinners' Association at Atlanta, November 14, 1901, Daniel Murray Pamphlet Collection. Library of Congress, Washington, DC, https://www.loc.gov/resource/lcrbmrp.t2003/?sp=2&r=-0.009,0.684,1.069,0.963,0.

[63] Edmonds, “The South's Industrial Task,” 6.

[64] Broughton, Tuskegee Visit¸ 13.

Madison Hall

Madison Hall is an Archivist at the National Steeplechase Museum in Camden, South Carolina. She graduated with her B.A. in History from Regent University in 2024 and is currently earning her master's in library and information studies at the University of Alabama. She is most interested in historical preservation, standardization for small museums, and American colonial and antebellum history.