Behind the Scenes at the Ballet: Body as Art and Business

Introduction

In the decade of the 1830s, there was a rise in ballet as an art form to be casually consumed by the mostly upper-class public, and with it, the idea of the basic archetypes for female characters that we still see today, such as the young and innocent girl and the provocative seductress. With the popularity of pointe [1] and the effortless dancing made popular in these performances by Marie Taglioni, who popularized this style in lead female dancers, the treatment of dancers behind the scenes and the character archetypes that became constants on stage became increasingly intertwined. The female characters that were being portrayed and written by prominent composers like Adolphe Adam and performed at famous venues like the Paris Opera House also made it considerably easier for the work of dancers like Taglioni to be diminished. The use of the female main character as a vision of innocence will be explored here through the uses of the ballets La Sylphide and Giselle, in relation to accounts of backstage and rehearsal encounters from Romantic and contemporary dancers.

A Dancer’s Training

The pointe style requires years of rigorous training and discipline. A dancer who has been training since the age of four or five usually does not prove themselves ready for pointe work until around age twelve. To earn their first pair of pointe shoes, a dancer must possess a minimum of five years of ballet practice, be a master of advanced techniques and performances on both demi-pointe [2] in standard ballet slippers, and flat foot, and be of a mature enough mental state, meaning they are old enough to understand the effects that pointe has on the body and all of its myriad potential injuries. In short, a dancer must fully commit themselves to their craft before earning their first pair of pointe shoes.[3] Once earned, the dancer usually practices basic technique en pointe for two or three years before attempting to perform a complex routine in a professional ballet. In the case of many professional dancers, ballet on flat foot begins at around age five, pointe is learned at age twelve, begins to be performed at fourteen, and auditioned at major companies at age seventeen to eighteen. Thirteen years of daily training in the form of stretching and technique work just to be considered almost a professional. This displays the dancers' dedication and talent in numerous ways, with their relentless work ethic, attention to minute detail in their performance, their patience in mastering such a delicate craft, and their sacrifice to take on this art form despite its numerous concerns for injury. Not to mention their ability to appear weightless when the force going into the box of the pointe shoe is nearly twelve times their body weight and their ability to tell complex and emotional stories while in these difficult positions.[4]

In contrast to its intentions to make the dancer’s movements look weightless and effortless, this style requires work and dedication from the dancer. As mentioned in “Romantic Illusions and Rise of the Ballerina”, Taglioni would practice “two hours in the morning dedicated to a series of arduous exercises, repeated many times on both legs and two hours in the afternoon on adagio movements… in which Marie honed and retained poses and postures of ballet… held each pose for the count of 100…she worked for an additional two hours (for a total of six hours per day), this time exclusively on jumps.”[5] This schedule exhibits her dance skills, as she worked diligently on her craft, overcame her setbacks daily and was able to evoke emotion and have a legacy with her audience. Achievement that no dancer up until that point had accomplished. Her schedule also set a precedent with audience members to expect women to make things look easy in multiple ways like appearing weightless, always graceful, and often silent against the stage. The appearance of weightlessness fetishized the thin body in the ballet industry.

Despite all of the work that ballerinas must put in in order to earn a contract with a professional company, once they are in the professional world, their skill is surprisingly low on the company’s list of priorities. Only in the ballet studio rehearsals and auditions, when the dancers are competing with one another for lead roles and seeking praise from their instructors, their skills become the top aspect of their job. In performance and how they present to the public, numerous elements of ballet as a career are presented as more important than a dancer’s actual talent, such as their youth, beauty, financial struggles, and even the characters they play, the costumes they wear, and the lighting used during their performances. All of these things contribute to the objectification of these dancers as prostitutes and means of financial gain, demeaning their personhood as a whole as the company places the dancers’ value in everything other than the very thing they have worked their entire lives to achieve.

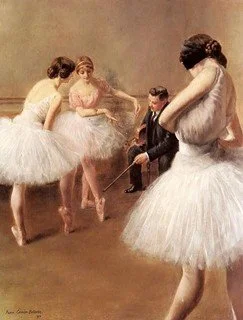

"Carrier-Belleuse, La leçon de ballet" by leo.jeje is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

The Ballets, Beauty Standards, and Characters

In the 1830s, ballet became an art form that upper-class citizens could use as an escape from everyday life. This ideology of escapism created a need for at least some of the material shown on stage to be light and palatable both in plot and appearance, so as to take away any political and social tension in the audience. This quickly became the job of the female leads and the styles of dance they were expected to master.

In the ballet La Sylphide, the title comes from mythical beings, equivalent to the German fairy-like beings known as Wili, one of whom dances in a vision for a young groom-to-be on the morning of his wedding. He is then completely entranced by the Wili , seeing her everywhere, unable to focus on the activities of his own wedding or his own bride, and, to his friends, exhibiting erratic behavior, as he is the only one who can see the sylph. While James the groom runs off with the sylph named Effie, his bride, collapses in tears over his lack of love for her.[6] The two main female characters in this work represent female archetypes at the time. Firstly, the role of the sylph, originated by Marie Taglioni, popularized the en pointe style which we see most commonly today in professional ballet. With the amount of influential, upper-class male patrons watching the show, it helped instill an idea that the girl herself should be graceful, elegant, young, and beautiful. She should be able to float around in the world of her story until some sort of great or tragic love seemingly happens to her.

In Giselle, which premiered at the Paris Opera House in 1841, the lead dancer Carlotta Grisi is described by Sarah Cordova, author of “Romantic Ballet in France: 1830–1850”, as “delicate and chaste all the while standing up for the love of her life and her passion for dance. She performed the mime and movement needs of the role with precision and clarity without overemphasizing them.”[7] In the ballet, the title character is a peasant girl who wins the heart of a duke but kills herself with his sword when she discovers his true identity as a peasant. She then becomes a Wili, a mythical spirit in the forest who lures men to dance to their death. As Wili, she puts her spell on almost all of the male characters, leaving only the Duke to cry at her grave.[8]

The description of the dancer as ‘chaste’ also contributes to one of the major contradictory expectations of women at this time and for many women today. Namely, the expectation of being sexually innocent while also compliant to fulfill male sexual fantasies. The expectation that all female characters in ballet be sexually clueless projected itself onto the patron’s view of the dancers, so that the wealthy men who donated money to the Paris Opera House, intrigued by these beautiful young girls, could expect them to fulfill their every wish and command.

As mentioned, the pointe style emphasized the dancers’ depiction as sexualized ethereal beings. The style first appeared in Germany and Italy, then practiced by Taglioni and brought to the Paris Opera House, where it then became the expected standard we see today.[9] The popularization of pointe also further enforced physical ideals of small feet for women. [10] This paved the way for ballet to further adopt what much of the outside world had previously held as the ideal for beauty in women: very small, and therefore, often young, thin and pale, with small hands and feet, delicate features, and a pretty face. This standard continues even to this day, with professional ballerinas such as Lauren Lovette being criticized well into their professional careers for not being skinny enough or having a “ballet body”.[11] Described in The New York Times article “What is a Ballet Body?”, castings in ballet look for a “short torso and long legs- what many would consider the ideal body for ballet.”[12]

Taglioni’s dedication to her craft was bred from a necessity to catch up to her peers due to her stature making her an “unlikely candidate” for professional ballet.[13] As described above, Taglioni was repeatedly told that she was too fat and ugly, and that her posture was so poor that she’d never succeed in ballet. Taglioni, however, quickly became the expected standard for all ballerinas to work just as hard as her and achieve the same level of weightless and graceful status at every rehearsal and performance. Thus trying to make it appear effortless, though any given move can take years to perfect. This appearance of having an ‘easy’ job makes it simple for wealthy patrons to think of themselves as better than the dancers on stage.

The characters they played, the styles they performed, and their identities as women in general all contributed towards their talents not being taken seriously by patrons. Even today, ballet is often not seen as a proper sport nor a proper application of the term ‘genius’ or ‘virtuoso’. When a patron sees a ballet with a woman who is young and thin, playing the part of a teenage girl, wearing flowy dresses, swooning over men, twirling around on her toes, and jumping up in the air with glee when her true love kisses her,and it is s taken by many as an open invitation to diminish her talent and intelligence, as she made the years of work look easy. Her ability to memorize hours of choreography and her work ethic to succeed in multiple seasons of professional performance were hidden behind a pretty face, and diminish her humanity, as even her own family could be bribed to send her away with an anonymous male patron at the end of the night.

Les Abonnés, The Patrons

The ballerina’s portrayal of innocence was complicated when the patrons were invited backstage. It was common practice that older and wealthier men would frequent the ballets shown at the Paris Opera House and be on the lookout for any one girl who caught their eye. Male patrons would then have access to the backstage areas, warm-up area, and hallways where the dancers would rest and get ready in order to “negotiate terms” with the girls' mothers about ways that the dancers could earn the man’s patronage.[14] In “Romantic Ballet in France”, Sarah Cordova describes this phenomenon, particularly regarding the premiere of Giselle at the Paris Opera House in 1841 saying “men, dressed in black tailcoats and top hats, asserting their privileged status derived from their associations with the worlds of business, of politics and the intelligentsia – have paid for the entitlement of entering the foyer de la danse to chat with the dancers.”[15] These men were often over 30 years older than the girls on stage and made up around a quarter of their audience.[16]

In the Paris Opera House in the 1830s, this patriarchal power was heavily exercised through processes of forced prostitution. This was furthered by the fact that the male dancers weren’t allowed to step foot in the Foyer de la danse after a show. The room was exclusively for girls and patrons. This reflected poorly, not on the patrons, but on the girls. While the patrons, known as les abonnés, were able to keep the specifics of their relationships quiet, it was common knowledge that the girls were made to flaunt themselves for money, creating the cultural stigma that the girls were gold diggers, social climbers, and sexually dirty and undesirable, so they were not to be associated with outside of the theater.[17] Events like these would later be documented and adapted in visual art, such as the works of Degas, cinemalike Black Swan, and literature such as Cathy Buchanan’s The Painted Girls.[18]

The Rehearsal Onstage, Edgar Degas Met Museum

This suggests that the image of these young women that les abonnés saw from the audience was the same as the dancers themselves. The dancers were seen as mere characters to be cast not only in productions, but in the patron’s lives. Seeing a woman dance on stage acting the part of a young and naive girl in love gave the impression that the girl would act that way off the stage too. This therefore made a patron feel justified not only in demeaning the dancer’s skill and hard work in their craft, but also their overall value as a person. For the patrons, it seemed completely reasonable to go backstage immediately after the production concluded and ask her mother or choreographer to spend the night with her. This was encouraged in 1831 by the manager of the Paris Opera House, Doctor Veron. He allowed men to pay for backstage access only to bring more money into the hands of himself and his theater at the expense of his young female dancers who couldn’t fight back at the risk of losing their jobs and often their family’s main source of income. [19]

During the 19th century, the Paris Opera House used the patron’s access to the foyer de la danse and the income that it brought to the studio to make its way out of financial hardship, making it dependent on an endless cycle of exploitation. In addition to this, the money that the dancers made from ticket sales and meetings with patrons would not only provide income for their lower-class families, but also move them further up in society, leading them to better jobs in the dance world and better chances of marrying rich. The young dancers needed these financial securities in order to survive, so they were pressured into being friendly and encouraging to male patrons who may want to meet with them.[20] For younger dancers, les adonnés could hold professional contracts over the girls' heads, meaning some girls wouldn’t be offered a contract until they agreed to be a patron’s mistress.[21] In short, most dancers hired by the Paris Opera House (hired only after apprenticing for free) worked for twelve hours a day, seven days a week, were expected to leave with men they didn’t know after almost every show to make extra money, and bring all of their income back home to feed their families as young as the age of twelve.[22]

The costumes being worn in ballet were also purposefully oversexualized for the enjoyment and entrancement of male patrons. Their plots were somewhat written to spark arousal in the male audience. In order to draw wealthy male patrons and their wallets into the foyer de la danse, dancers were specifically made to look like and portray the perfect women, both in movements and costumes. In Cordova’s words, “The radical new look of pointe work and adagio, of effortlessly graceful feminine bodies dressed in tutus disguised the increasingly strenuous technical virtuosity and extensive training for these performances,”[23] thus oversexualizing them. When discussing the plots of Giselle and La Sylphide, Tamara Gebelt, a scholar at the Louisiana State University, wrote “Both love stories employ a common theme of the period, the melancholic notion of man striving to attain the unattainable. Similarly, both concern a human male's love for an ethereal female.” [24]This plot may have also encouraged the notion that the women they saw being chased romantically and sexually on stage were also wanting and deserving of being pursued on stage. In modern terms, Veron was making his dancers seem like they were “asking for it.”[25] In addition to the role of the female characters themselves within their stories, this process of blatant over-sexualization sparking arousal and monetary gain for the company, almost entirely squashed any notoriety that the dancers may have had as virtuosos or talent to be taken seriously at all.

Marie Taglioni's costume for La Sylphide featured an off-the-shoulder bodice and a skirt whose length would have been considered highly risqué for the time, as women’s dresses typically extended to the floor and fully covered the arms, chest, and shoulders. The design highlights the bold departure from contemporary norms in both fashion and performance. Taglioni’s stature, often criticized during her career as overweight and unattractive by conventional standards, contrasts sharply with her enduring legacy as a pivotal figure in the history of ballet.

The ballets themselves also have a heavy association with innocence because of the way they employ excessive amounts of white in their costumes, lighting, and setting design. This is described by Cordova as ‘ballet blanc’. This practice became popular when used in Giselle and La Sylphide to accentuate the setting of underwater scenes, show the identity of Wilis as angelic figures, and, more subconsciously, to show the youth and innocence of all of these female characters. This also remained relevant in multiple countries for decades after, with ballets such as Swan Lake also considered ballet blanc. This practice highlights the double standard created that women, both on stage and in society itself, should be innocent in order to be desirable by men.

It is roles like that of the female leads of Giselle or La Sylphide which, because of their massive popularity and expansion of the art of ballet through the ideals and desire that they spread, caused ballet to become more and more of the female-centric sport that we know today. Ballet, and dance in general, perhaps wouldn’t be so directed towards women as a hobby and career if it hadn’t been for the massive success of ballet blanc and its characters.[26]

Conclusion and Looking Forward to Modern Ballet

In Romantic French ballet, roles were purposefully written to oversexualize professional dancers, demean their virtuosity, and bring money into the pockets of the Paris Opera House by enticing wealthy male patrons with the promise of sex from a beautiful young girl. These aspects of ballet became widely spread because of elements such as the rise in popularity of the pointe style, the shorter skirts and lower necklines of their costumes, and the practice of letting male patrons into backstage areas. All of these things combined with many others created an environment in which the talent and even personal will were taken away from these girls in order to sell tickets, and further established the expectation of young, naive, and innocent girls not only in art, but also in French society off-stage.

In her New York Times article, Gia Kourlas also talks about why these standards exist for ballerinas and how it belittles their skill. She says “It comes down to how the body moves through space…our body is the art.’”[27] This elaborates on how the treatment of ballerinas affects their art form. Comments from their instructors can be perceived as degrading if dancers are judged not to be pretty, skinny, or fair enough. This causes the potential for many dancers to develop these ideas as truths about themselves and either stop pursuing ballet as a way to redeem their positive mental health, or spend the entire rest of their lives working towards an impossible ideal of what they should look like and repeatedly hurt themselves mentally and physically in the process. Many ballerinas for the entirety of the craft’s history have developed eating disorders as a direct result of their instructors telling them to lose weight and the inherent competition in class and performance to compare themselves to other dancers.

Ballet is largely a field that has implanted its significance in multiple cultures through its ability to use young women for profit oftentimes at their own expense. Around 78% of ballet dancers today identify as female, while 72% of their directors identify as male. [28] This shows that, even today, the industry is built on much older men having almost full control over the careers of young women, from their movements to their makeup and costumes to their income.

End Notes

[1] Pointe here refers to the common ballet practice that originated in France through the style of Maria Taglioni. The style requires that dancers wear shows with a box-like structure in the toe, allowing dancers to stand on the tips of the toe. These shoes are referred to as pointe shoes and the position of standing on the tips of the toes is referred to as being en pointe.

[2] Demi-pointe refers to a position where the dancer places all of their weight on the balls of their feet. In pointe shoes, demi-point is a position the feet pass through to get to the pointe position, therefore it is a standard preparatory practice for dancers hoping to earn their pointe shoes.

[3] Selina Shan, “Determining a Young Dancer’s Readiness for Dancing on Pointe.” Current Sports Medicine Reports 8, no. 6 (2009): 295–99. https://doi.org/10.1249/jsr.0b013e3181c1ddf1.

[4] Shah “Determining a Young Dancer’s Readiness for Dancing en Pointe”.

[5] Jennifer Homans, Apollo’s Angels: A History of Ballet (New York: Random House Trade Paperbacks, 2011), 139.

[6] Adolphe Nourrit and Jean-Madeleine SchneitzhoeIer. “La Sylphide Royal Danish Ballet,” posted on December 3, 2020, by Astrid, YouTube, 1:02:55, www.youtube.com/watch?v=R_RFxSLar2A .

[7] Sarah Davis Cordova, The Cambridge Companion to Ballet (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 113.

[8] Adolphe Adam and Jean Coralli. “Giselle Ballet - Full Performance - Live Ballet.” posted on November 22, 2020, by Imperial Classical Ballet, YouTube, 1:43:05, www.youtube.com/watch?v=VroMXEDLTq8. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8420G154.

[9] Homans, Apollo’s Angels, 142.

[10] Homans, Apollo’s Angels, 142.

[11] Gia Kourlas, “What Is a Ballet Body?,” The New York Times, March 3, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/03/arts/dance/what-is-a-ballet-body.html

[12] Kourlas, “What is a Ballet Body?”

[13] Homans, Apollo’s Angels, 137.

[14] Lynn Garafola, “The Travesty Dancer in Nineteenth-Century Ballet,” Dance Research Journal 15/18, no. 2/1 (1985): 35–40, https://www.jstor.org/stable/1478078.

[15] Cordova, The Cambridge Companion to Ballet, 113.

[16] “Pimps, Poverty, and Prison: The Corps de Ballet in Nineteenth Century France.” Essay, n.d.

[17] “Pimps, Poverty, and Prison: The Corps de Ballet in Nineteenth Century France.” Essay, n.d.

[18] Cathy Marie Buchanan, The Painted Girls (London: Blackfriars, 2017).

[19] Cordova, The Cambridge Companion to Ballet, 124.

[20] Sebrena Williamson, “Exploitation in Ballet History: Prostitution at the Paris Opera Ballet.” The Collector, October 12, 2023, https://www.thecollector.com/history-ballet-paris-opera/.

[21] “Pimps, Poverty, and Prison: The Corps de Ballet in Nineteenth Century France.” Essay, n.d.

[22] Williamson, “Exploitation in Ballet History: Prostitution at the Paris Opera Ballet.”

[23] Cordova, The Cambridge Companion to Ballet, 120.

[24] Tamara Lee Gebelt, “The evolution of the romantic ballet: The libretti and Enchanter characters of selected romantic ballets from the 1830s through the 1890s,” (Louisiana State University, 1995) https://doi.org/10.31390/gradschool_disstheses.6012.

[25] Cordova, The Cambridge Companion to Ballet, 124.

[26] Cordova, The Cambridge Companion to Ballet, 121.

[27] Kourlas, “What Is a Ballet Body?”

[28] “Ballet Dancer Demographics and Statistics in the US[2024]: Number of Ballet Dancers in the US.” Zippia, April 5, 2024. https://www.zippia.com/ballet-dancer-jobs/demographics/.

Steph Stone

Steph Stone is a senior at Boston University studying historical musicology with a specialization in North American Punk history. She is a writer for Roots Magazine, Music Mecca Magazine, and a French translator for The Opera Journal. She also rambles about music history on various social media platforms under the name meantoast.