Utilitarian Aesthetics: The Function of Art and Individuality in John Stuart Mill and George Eliot's Middlemarch

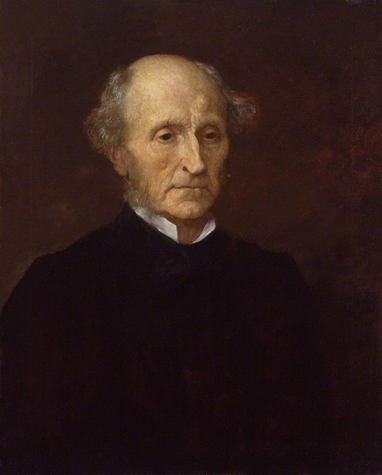

In his two seminal works, On Liberty and Utilitarianism, John Stuart Mill, one of the leading philosophers of the 19th century, argued for the import of a broadened conception of individuality and the general utilitarian good of intellectual and aesthetic pursuits. Utilitarianism is a philosophy that promotes happiness above all else, it is often understood under the motto “the most good for the greatest number of people”.

Mary Ann Evans, who wrote under the male pseudonym George Eliot, was a colleague of Mill at the Westminster Review, and a prominent 19th-century novelist who expressed similar beliefs to Mill in her 1871 novel, Middlemarch. Her novel brought together many areas of concern with society, largely having to do with the deterministic factors of gender and its deprivation of utility for women, with a realistic literary aesthetic. In her iconoclastic essay, “Silly Novels by Lady Novelists”, she expressed her disdain for the state of literature in her contemporary world which limited the conception of female creativity and intellectual pursuit through its emphasis on popularity and the novelty of female authorship over genuine talent or ability. Furthermore, Professor Darrel Mansell Jr., a scholar of 19th-century literature, in his journal article, “Ruskin and George Eliot’s ‘Realism’”, dissects the form of aesthetic realism used in the novel explaining how Eliot creates the reality of Middlemarch as a reflection of her individual mind rather than as an exact reproduction of the world. Middlemarch was intended to be the ultimate all-encompassing novel of Eliot’s career, to take on questions, concerns, and philosophical views on society, gender, and individuality; what Eliot magnificently is able to produce, by taking together Mill’s philosophy and her own concerns about feminine identity and the literary world, is an aesthetic expression of the argument for Millian utilitarianism.

Utilitarianism promotes the maximization of utility, or happiness. It holds that pleasure is the only thing with inherent value and that the best actions are those that promote the most pleasure or utility. The philosophy predates Mill and was usually seen as a moral justification for debauched hedonism. Mill believed in the consequentialist pleasure-based framework of utilitarianism but felt that its focus on hedonistic tendencies was misguided. He redefined and broadened the field of utility producers in his work Utilitarianism:

It is quite compatible with the principle of utility to recognise the fact that some kinds of pleasure are more desirable and more valuable than others. It would be absurd that while, in estimating all other things, quality is considered as well as quantity, the estimation of pleasures should be supposed to depend on quantity alone… now it is an unquestionable fact that those who are equally acquainted with, and equally capable of appreciating and enjoying, both [pleasures of higher and lesser nature], do give a most marked preference to the manner of existence which employs their higher faculties.[1]

Naturally, as in all things that may be estimated, pleasure has a hierarchy of significance and utility produced for the individual. Therefore, it logically follows that pursuits of the higher order, such as aesthetic and intellectual endeavors, are of much greater benefit to the individual as opposed to the hedonistic emphasis created by the precursors to Mill who focused on the animalistic and hedonistic utility of sex, drugs, and rock and roll. In pursuit of a life of maximized pleasure, Mill believed we should turn to the employment of the mind and its higher faculties as opposed to the sybaritic use of the body. Mill took these utilitarian beliefs and adapted them to social philosophy. In On Liberty, he discussed how members of society, both for the individual and in the aggregate, can better themselves through his conception of utility:

But it is the privilege and proper condition of a human being, arrived at the maturity of his faculties, to use and interpret experience in his own way. It is for him to find out what part of recorded experience is properly applicable to his own circumstances and character… The human faculties of perception, judgment, discriminative feeling, mental activity, and even moral preference, are exercised only in making a choice. He who does anything because it is the custom makes no choice… Human nature is not a machine to be built after a model, and set to do exactly the work prescribed for it, but a tree, which requires to grow and develop itself on all sides, according to the tendency of the inward forces which make it a living thing.[2]

Individuality, for Mill, is the personal ability to self-determine without being imposed upon by the rules of society; the freedom to make educated choices, and the ability to carve out and understand one’s desired role in the world. To accomplish this, Mill wants us to turn to the perusal of the canon of experience. Through intellectual philosophy or great feats of literature, one develops an understanding of their own conception of the good life. Not only do works of the intellect and art produce higher forms of utility for each individual, but they lead us to a broader conception of the way we live our lives through their showcasing of alternative experience. When art or philosophy presents the world to its audience, the reader develops a greater understanding of themselves and their place in the world and society through viewing the model of another’s life; what this accomplishes is an enhancement of the personal sense of individuality and the societal conceptions of what an individual can be. In this way, when more members of society undergo this process, in the aggregate, society becomes less restrictive and far more open to a larger sense of the self for all people. As choice presents itself, one who has experienced this form of utility will be able to choose for themselves the best course of action and not bow down to the deterministic tendencies of the times and society, thereby creating for themselves a better, freer, life. And, as Mill hopes will happen, this cycle of utility broadening our conceptions will begin to affect the social zeitgeist, opening-up the deterministic boxes of possibility in which society places every individual based on sex, gender, race, etc.

Similar to Mill’s call for a widened sense of individuality for the benefit of the individual and society in the aggregate, George Eliot called for the enhanced conception of female authors for the benefit of the conception of the female intellect. Before Eliot ventured into the world of novels, in 1856 she wrote her essay Silly Novels by Lady Novelists in which she railed against the publishing world of her time. She believed its showcase of feminine authorship limited societal conceptions of what a woman’s mind could do:

The foolish vanity of wishing to appear in print, instead of being counterbalanced by any consciousness of the intellectual or moral derogation implied in futile authorship, seems to be encouraged by the extremely false impression that to write at all is a proof of superiority in a woman. On this ground we believe that the average intellect of women is unfairly represented by the mass of feminine literature, and that while the few women who write well are very far above the ordinary intellectual level of their sex, the many women who write ill are very far below it. So that, after all, the severer critics are fulfilling a chivalrous duty in depriving the mere fact of feminine authorship of any false prestige which may give it a delusive attraction, and in recommending women of mediocre faculties—as at least a negative service they can render their sex—to abstain from writing.[3]

Although this essay predates Mill by a few years, we can clearly see the same concerns and sentiments around individuality and conceptions of the individual echo through her prose. According to Eliot, the fact that one can write does not mean that one should write. When the novelty of a female author is enough for a book to succeed, then any woman with a pen can write a book regardless of genuine talent or ability. This phenomenon largely restricts and limits society’s conception of what a woman can do when all that is shown is mediocrity sold for its novelty. Art cannot produce utility and be used to explore the record of human experience when it is crafted by those women whose intellect are far below the “ordinary intellectual level of their sex”. Women who write well, on the other hand, exercise and showcase a level of intellectuality far above that of their sex. According to Eliot; they have the ability to prove to society the genuine abilities of women and to produce works used for the development of individuality. Eliot shows us how a Millian utilitarian approach to literature will be better for women, and, therefore, for society.

This leads us to Middlemarch: A Study of Provincial Life. Written over the course of 8 books, or sections, the narrative follows many different strands of provincial life as Eliot dissects the interweaving relationships and new ideas which are permeating through her invented reality. Before her narrative begins, Eliot, in the preface, positions her work at the intersection of the ideas and texts that we have been discussing [4]. She presents the life of St. Theresa as an archetype for a woman with a yearning to do good who is restricted from action by her femininity. Eliot writes:

That Spanish woman who lived three hundred years ago, was certainly not the last of her kind. Many Theresas have been born who found for themselves no epic life wherein there was a constant unfolding of a far-resonant action; perhaps only a life of mistakes, the offspring of a certain spiritual grandeur ill-matched with the meanness of opportunity; perhaps a tragic failure which found no sacred poet and sank unwept into oblivion.

When one reads Eliot for the first time, the sheer force of her language is intoxicating. Who upon reading her Miltonian prose can help but feel educated, exalted, and empowered by its strength? This reaction and admiration for the text is what Mill means by the pleasure attained through utility of the higher order.

Middlemarch was published in 1871, at which point it was well known that George Eliot was, in fact, a woman. We can thereby easily place Eliot, and the popular conception of her ability, within her category of women who showcase a level of intellectuality far above that of their sex, whose literary abilities both produce utility and broaden the conception of what a woman’s mind can create. Aside from the grandiose language, in the preface Eliot sets up the rules and ideas which will permeate throughout the text; she presents the thesis for her argument. Her tale will showcase those women whose minds did not match their social lot in life. Those with a “spiritual grandeur” who lacked any ability to bring forth all they had to offer and wished to accomplish; those who have faded into obscurity though they ached for a greater purpose. These Theresas have, as yet, found no sacred poet to express their sorry lot, so Eliot will sing their song and lift their stories from oblivion. Later in the preface, she discusses individuality and its relation to feminine existence:

…later-born Theresas were helped by no coherent social faith and order which could perform the function of knowledge for the ardently willing soul. Their ardour alternated between vague ideal and the common yearning of womanhood; so that one was disapproved as extravagance, and the other condemned as a lapse. Some have felt that these blundering lives are due to the inconvenient indefiniteness with which the Supreme Power has fashioned the natures of women: if there were one level of feminine incompetence as strict as the ability to count three and no more, the social lot of women might be treated with scientific certitude. Meanwhile the indefiniteness remains, and the limits and variation are really much wider than any one would imagine from the sameness of women’s coiffure and the favourite love-stories in prose and verse.[5]

Without an expansive self-understanding and sense of individuality wrought through utilitarian pursuits and an understanding of human experience, these talented women have no guide for their ability. Their lives are thereafter shaped by a kind of societal determinism: lacking any ability for knowledge, they never gain access to the outlet of individuality and are forced into being, what Mill calls in On Liberty, “a machine to be built after a model, and set to do exactly the work prescribed for it”. They are condemned for being extravagant or failures as they aimlessly work and yearn for a greater purpose but fail to latch themselves to anything fruitful as a consequence of being “helped by no coherent social faith and order which could perform the function of knowledge for the ardently willing soul”. Men might be inclined to see the failures of women as evidence of their naturally inferior disposition, but Eliot believes that it is a product of society’s treatment of women. As much as women might wear the same clothes or hair or like the same books, the differences between all women are stark, and no category or defining feature can be affixed to the concept as broad and as complicated as a woman. The preface situates us with the argument that Eliot makes within her novel: women of ability are not given access to higher order utility and are thus limited by societal conceptions of individuality. The argument is made even more powerful through it being rationally and intelligently posed by a woman.

"Woman writing letter and bond" is marked with CC0 1.0.

Turning to the narrative text of Middlemarch, we leave behind the metacommentary on Eliot’s purpose in writing the novel and look instead at how Eliot portrays her argument through the character of Dorothea Brooke, showing how the societal treatment of women manifests itself maliciously throughout her story. In this way, she constructs a philosophical argument about society through the aesthetic form. In the first pages of the book, Dorothea is presented as the St. Theresa of the story, a woman of ability, striving to use it. We see this desire seep into the psychology of Dorothea as we are told of her discontent in life and her desire for something greater:

For a long while she had been oppressed by the indefiniteness which hung in her mind, like a thick summer haze, over all her desire to make her life greatly effective. What could she do, what ought she to do? - she, hardly more than a budding woman, but yet with an active conscience and a great mental need, not to be satisfied by a girlish instruction comparable to the niblings and judgments of a discursive mouse…The intensity of her religious disposition, the coercion it exercised over her life, was but one aspect of a nature altogether ardent, struggling in the bonds of a narrow teaching, hemmed in by a social life which seemed nothing but a labyrinth of petty courses, a walled-in maze of small paths that led no whither, the outcome we sure to strike others as at once exaggeration and inconsistency…The union which attracted her was one that would deliver her from her girlish subjection to her own ignorance, and give her the freedom of voluntary submission to a guide who would take her along the grandest path.[6]

That same indefiniteness with which Eliot discusses the archetype of St. Theresa is endowed upon Dorothea. With this, we turn our attention to Dorothea as the modern Theresa, as someone wanting more out of life, yet having her passion yoked to her unfortunate social lot. Social custom has dictated that an adequate education for a woman of the upper classes is tutorials in singing, sewing, music, and the like - teaching women to be wives and mothers. Dorothea is trapped within this lackluster definition of a woman and her purpose when her mind and passion ache for some grander function. Kept from Millian utility, she has had no means of creating a rigorous sense of individuality and consequently she doesn’t know what to do with herself, how to wield her power, how to understand the world and identify her desired function in it. Dorothea becomes so desperate for this worldly understanding that it begins affecting her ideas on marriage. To her, marriage is ideally not a partnership between lovers, nor even an economic contract, but a sort of apprenticeship wherein she will finally learn what she needs to exist properly. Dorothea wishes to submit herself to the will of another, to have her agency removed so that her mental faculties might flourish. This is the state of women in society. Eliot presents this suffering vividly by bringing us into the interior thoughts of Dorothea, showing how this desire manifests itself and dangerously alters her conception of how she should live her life.

Eliot is often paraded as the doyenne of realism. Her use of psychological realism makes her characters relatable, lovable, sympathetic, and real. In the quote above, we begin to understand and pity Dorothea through the insight we are granted into her psychological interiority. In Professor Darrel Mansell Jr.’s article “Ruskin and George Eliot’s ‘Realism’”, he discusses Eliot’s unique sense of realism which incorporates reality with her subjective view. In discussing Ruskin’s literary criticism as it relates to Eliot, Mansell notes “She is anxious not to fall into Ruskin’s category of inferior artists who reproduce the real world ‘like human mirrors’; rather, she wants to produce art which is the reflection of her own mind. She does not claim to be objective”.[7] The world of Middlemarch is designed around Eliot’s express purpose in writing the novel; she doesn’t wish to simply show us the real world but to subtly pass judgment and present her thoughts on it. We can apply this to our reading of Eliot’s presentation of Dorothea to understand the literary process of crafting the argument on utility and its dangerous absence within the education and mindset of women. We can see Dorothea’s desire to submit herself as rather unrealistic in nature. If the function of knowledge is to create individual freedom, then why would she wish to lose her agency when the very thing she is craving is agency? This reaction is incredibly extreme and somewhat out of character for Dorothea, a woman whose character is often restrained by both her femininity and her deep religious convictions. The question remains: why would Eliot, the ultimate realist whose goal is to showcase the true effects of the societal treatment of women, make Dorothea react in this extreme fashion? The answer seems clear from Mansell’s essay: in dramatizing the suffering and wants of Dorothea, the reader is drawn in at a larger degree toward sympathizing with her and her cause. We see here the development of an overarching strategy which Eliot uses to present her argument; reality is presented in a subjective light, slanted in a wholly realistic manner. Middlemarch acts as a mirror of Eliot’s mind, not of the real world, towards the end of a more sympathetic presentation of the argument.

Dorothea’s wish for an instructive marriage eventually comes true as she marries Mr. Casaubon, a local clergyman with scholarly ambitions who she believes will be her guide through the great canon of experience. On their honeymoon in Rome, she frequently meets with an aspiring artist and scholar, Will Ladislaw, the cousin of Mr. Casaubon. As they tour the art galleries of Rome, Eliot pivots her argument from the manifestations of a lack of utility towards the desired function of art and higher utility as Dorothea begins to discuss her thoughts on art with Will: “I should like to make life beautiful - I mean everybody’s life. [Dorothea said] And then all this immense expense of art, that seems somehow to lie outside life and make it no better for the world, pains one. It spoils my enjoyment of anything when I am made to think that most people are shut out from it”.[8] Dorothea here aligns herself with utilitarianism - wishing art to have a function for the most good. This wish relates largely to changing artistic trends within the 19th century. The Pre-Raphaelites, an art movement distinctly associated with understanding figurative and psychological reality, emerged in England around the time when Eliot was writing. Rosetti, Millais, Waterhouse, and others were artists with a distinct wish to showcase reality and experience through the aesthetic form, similar to Eliot. Literature and art from before this period of Victorian artistic realism were often romantic in nature, showing the ideal, the mythological, or the fantastic over the truth of everyday life. The art that Dorothea is experiencing in Rome is that of the Renaissance: of romance, and of myth. Without a rigorous classical grounding, access to these works is largely restricted; Dorothea herself cannot access their message or beauty. She clearly wants art to be a means of utility, a means for making one’s life beautiful and individualistically strong; however, when its form is unrealistic, or its imagery can only be understood through a mastery of the Western canon, then art cannot be used as a means of developing individuality; the fantastic or the unrealistic cannot be as easily used for the development of individuality - a process that requires a study of human experience.

This discussion connects with Eliot’s essay Silly Novels by Lady Novelists: Art is only useful for society when it can be accessed and used for the development of individuality. The masters of the Renaissance are hardly comparable to the mediocre female novelists of the 19th century, but the use of their works is comparable when neither is available to the masses as a means of developing utility. What Eliot is calling for, through Dorothea, is for art to be accessible to the public so that it might benefit the pursuits of individual growth for as many people as possible. Art does not inherently need to be didactic or promote individuality, but its function can be used in a didactic way when it embodies tangible realities of the human experience. The realist aesthetic, used in the paintings of the Pre-Raphaelites and the novels of George Eliot, is easily accessible, showing realities of human experience which easily allows for the effortless exercise of higher faculties and the furtherance of individuality. In this way, realist art simultaneously acts as a medium for the utilitarian good of society through its educational capabilities and its mass enhancement of individuality. Dorothea acts as the mouthpiece of Eliot, calling for art to be exactly as Eliot wishes it to be: calling for art to be in the vein of Middlemarch.

When Dorothea and Mr. Casaubon return from Rome, she begins to aid her husband in his construction of a scholarly text on the subject of European pre-Christian mythologies. Through her aiding him in his studies, she begins to develop for herself a Millian sense of individuality as she works her way through works of scholarly literature. As she begins to learn, her subjugation to her husband becomes increasingly difficult to endure; her mind is becoming free, but her lot in life has not followed. Rather suddenly, Mr. Casaubon falls ill and rapidly passes away. In his will, he dictates that no property will be given to his cousin Will Ladislaw, and he leaves a proviso that Dorothea will void all rights to her inheritance of his estate if she decides to wed Ladislaw. Dorothea reflects upon his will and his last commandments to her as he departs the mortal plane; the narrator tells us of her:

But now her judgment, instead of being controlled by duteous devotion, was made active by the embittering discovery that in her past union there had lurked the hidden alienation of secrecy and suspicion. The living suffering man was no longer before her to awaken her pity: there remained only the retrospect of painful subjection to a husband whose thoughts had been lower than she had believed, whose exorbitant claims for himself had even blinded his scrupulous care for his own character, and made him defeat his own pride by shocking men of ordinary honour…Mr. Casaubon had taken a cruelly effective means of hindering her: even with indignation against him in her heart, any act that seemed a triumphant eluding of his purpose revolted her.[9]

When her captor has departed, the veil over Dorothea’s eyes has been lifted and she finally understands the truth of the nature of her marriage and her husband. Far from the great intellectual who could lead her from her stupidity, which she had always wished him to be, Casaubon turned out to be a pompous aristocrat who produced nothing substantial or accurate throughout his scholarly odysseys. Far from a proud and confident man of stoic nobility, he was a jealous paranoid fool who tried to keep his hold over her as much in death as he had in life. Dorothea’s idea of marriage was a union in which she could be taught how to live her life, where she could learn to derive individuality through the utility of education and the exercise of the higher faculties. In pursuing this idea, she submitted herself to the mind of Casaubon, a man claiming to be far more than he was. Ultimately, Dorothea’s misery in ignorance is displaced by the misery of her submission. She has been subject time and time again to societal custom of marriage and femininity over her own will. Her individuality was never able to develop, she never had access to the benefits of higher utility, resulting in a deterministic storyline of suffering leading to more suffering where her choices were never made based on her own preference but on the preference of society.

The silver lining of her husband’s death is that, while he retains some power over her through his will, Dorothea begins to develop her mind and powers in a way which she sees fit; she is allowed to emerge from the depths of her submission. We begin to see a change in her disposition when she is discussing her life as a widow. When it is suggested that Dorothea reenter society, and take herself out of the drab and lonesome library of Lowick so that she might not go mad, Dorothea replies:

‘I never called everything by the same name that all the people about me did,’ said Dorothea, stoutly. ‘But I suppose you have found out your mistake, my dear,’ said Mrs Cadwallader, ‘and that is proof of sanity.’ Dorothea was aware of the sting, but it did not hurt her. ‘No,’ she said, ‘I still think that the greater part of the world is mistaken about many things. Surely one may be sane and yet think so, since the greater part of the world has often had to come round from its opinion’.[10]

Dorothea, in her newly found freedom, begins to push back on society. Instead of following the custom of calling things by what everyone else calls them, she observes and understands the world herself, and can name things accordingly. This conversation is a microcosm for the change within Dorothea’s mindset. She begins to resist her conformity to the forces of society, allowing her own mind to develop as it sees fit. Dorothea’s remarks and mental shift lead us back to Mill in On Liberty; the function of individuality is to be able to live a life in freedom rather than in subservience to society, popular opinion, and custom. Dorothea begins to understand this and that the rules of the world are arbitrary and not the be-all end-all rules which must govern a life. Her only previous outlet for mental freedom was through the social custom of an oppressive marriage, but her current state has been enriched by pursuits of the higher order and she can now express her own thoughts and her own mind freely, even if it contradicts the grain of society.

For the next several books of Middlemarch, Eliot focuses on the other lives in her portrait of provincial life. In the final book, the story culminates when these stories begin to aggressively intersect and affect one another. Two of the central figures in the narrative of Middlemarch are Dr. Lydgate and his wife Rosamond, another unhappy couple whom Eliot discusses. Rosamond is an extravagant woman who leads Lydgate into great amounts of debt. In her anger with her husband, Rosamond turns to Will Ladislaw as a favourite and companion. One day, Dorothea catches Rosamond and Will in a moment of heightened emotion, believing she has uncovered an affair. Her initial anger is quickly displaced by sympathy as she suddenly realizes that her anger is out of the love she feels for Will and her inability to be with him owing to Mr. Casaubon’s will. This sympathy begins to manifest itself as a function of her utilitarian disposition, as part of her want to do the most good in the world:

All this vivid sympathetic experience returned to her now as a power: it asserted itself as acquired knowledge asserts itself and will not let us see as we saw in the day of our ignorance. She said to her own irremediable grief, that it should make her more helpful, instead of driving her back from effort…She yearned toward the perfect Right, that it might make a throne within her, and rule her errant will. ‘What should I do - how should I at now, this very day, if I could clutch my own pain, and compel it to silence, and think of those three?’ It had taken long for her to come to that question, and there was light piercing in the room. She opened her curtains, and looked out towards the bit of road that lay in view, with field beyond, outside the entrance-gates…Far off in the bending sky was the pearly light; and she felt the largeness of the world and the manifold walkings of men to labour and endurance. She was a part of that involuntary, palpitating life, and could neither look out on it from her luxurious shelter as a mere spectator, nor hide her eyes in selfish complaining.[11]

This is the height of Dorothea’s arc. The emotion that has frequently held her back in life for its naivete and foundations in ignorance turns into the means by which Dorothea can understand her fulfilled sense of self. Her emotion becomes the “coherent social faith and order which could perform the function of knowledge for the ardently willing soul”[12] that women lack. She has been spurred by her wish to be more than a spectator or a damsel in distress. No longer will she be the woman looking out from her window, wanting for the outside, but she will be part of the palpitating life which she has so long observed. This study of the outside world, both literally at her window, and through scholarly works, has been her education of the canon of experience which has allowed her to develop individuality, has allowed her to act the way she sees fit, despite what society expects of her because of her gender. This moment of realization is endowed with an aura of divinity. As Dorothea surveys the world, she sees the “pearly light”, a term often used to refer to heaven and its holy gates, and she feels the largeness of the world. This moment, for Dorothea, is her stepping through those holy gates, leaving behind the world of suffering which she has experienced, and entering the world of her individualistic ascendancy where she can pursue her desires and the ends of her moral beliefs.

Dorothea eventually weds Will, taking hold of her desires and forgoing the life which everyone had expected of her, that of a wealthy provincial widow, for the life of a wife to a socially inferior politician. In the conclusion, Eliot passes judgment on her characters’ lives and makes more clear her point in constructing Dorothea’s storyline. She tells us of her heroine that:

Dorothea herself has no dreams of being praised above other women, feeling that there was always something better which she might have done, if she had only been better and known better. Still, she never repented that she had given up position and fortune to marry Will Ladislaw…Many who knew her, thought it a pity that so substantive and rare a creature should have been absorbed into the life of another, and be only known in a certain circle as a wife and mother. But no one stated exactly what else that was in her power she ought rather to have done.[13]

In the end, the happy ending of Dorothea’s individualist ascendancy is overturned by the constant presence of the continuous determining factor of her life: her gender. While she is finally able to live the life she wants, her grand desires to do good in the world are unfulfilled and she becomes known only for her femininity and her marriage rather than her mental abilities. The depressing reality of this is that she has no alternative. Society has no use for women of her kind, no use for the Theresas of the world, besides motherhood and marriage. She never wanted to be praised, but she always wanted to be useful, and that dream was killed by the world, even if she had managed to develop her sense of individuality. This scene is deeply disturbing for readers, it comes very shortly after Dorothea’s moment of ascendancy, her moment of understanding her purpose; a purpose never fulfilled. We again turn to Mansell’s paper to understand Eliot’s purpose here. In presenting Dorothea’s moment of realization in such a dramatic and emotional light, Eliot makes its eventual overturning significantly more painful for Dorothea and the reader to endure. By creating this extreme reversal, Eliot again, through crafting a more dramatic and extreme version of reality, draws the sympathy of the reader towards Dorothea and her cause. On this more melancholic note, Eliot moves toward her concluding words in which she returns to the preface:

Certainly those determining acts of her [Dorothea’s] life were not ideally beautiful. They were the mixed result of young and noble impulse struggling amidst the conditions of an imperfect social state…But the effect of her being on those around her was incalculably diffusive: for the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.[14]

She asserts once more that society is failing these women. The fatalistic determinism of femininity continuously casts the lots of these remarkable people into obscurity for no reason besides sexist social custom. Even Dorothea, with her painful process of developing individuality and individual freedom, could not break from it. The function of Middlemarch has been to sing the songs of these women, to show their pain and their potential, and to urge the reader to change how they conceive of women and their abilities. In this way, Dorothea’s effect is “incalculably diffusive”. Her life becomes that of an archetypal sainted martyr who suffers so that others might see her plight and fight for a better life for those future Dorotheas. Her story allows the reader to develop the individuality which was her only strength, her path towards some semblance of freedom. Middlemarch, as a text, is a tenet of the Western literary canon and the canon of experience which Mill urges us to understand to develop ourselves. When we can all do this, when we can all understand the experience of Dorothea, society as a whole is bettered. As each individual changes their view, society will follow in the aggregate until the custom of socially conservative traditionalist sexism can be abolished, and no future daughters will suffer on the basis of sex. It’s not enough that one woman can undergo this process, what we require is for each person to live their lives, as Mill describes, “according to the tendency of the inward forces which make it a living thing”.

"Portrait woman writing Henry Maull" by J. Paul Getty Museum is marked with CC0 1.0.

Middlemarch presents and supports utilitarianism on every level. On the conceptual level, Middlemarch is a text whose realistic aesthetic allows the reader to develop a Millian sense of individuality as they are presented with a portrayal of human experience. Interestingly, Middlemarch does not only broaden every individual’s personal conception of themselves, but it also moves the reader to further consider their assumptions and understanding about women and their abilities. Throughout the text, Eliot proves herself to be a great novelist, both for her literary skill and her ability to craft iconic characters. Through an appreciation of the story of Dorothea, as well as an appreciation of the female author, readers develop for themselves a broadened conception of women in a society; a goal which Eliot makes explicit in her essay Silly Novels by lady Novelists. On the narrative level, we see the argument for this use of higher utility played out through the character of Dorothea. Without the experience of utility through art, and the exercise of her mental faculties, we consistently see Dorothea ache after a sense of purpose, and suffer for lacking an understanding of herself and her place in the world. Mansell’s essay helps us to understand that Eliot emphasizes the pain and effect which this lack of utility has on Dorothea in order to make her argument on the virtues of utility more clear and sympathetic. When her suffering begins to be displaced by her sojourns into the scholarly world, her eventual ascendancy is halted by her femininity. Dorothea’s story is meant to show the reader the danger of the current affairs of Eliot’s world, to present a reality which can be used as an understanding of human experience and thus as a means for changing the world for the better. Eliot writes her novel as the aesthetic embodiment of Mill’s utilitarian philosophy; a text which produces utility and broadens individuality for the reader, a text which argues for art to have that very same use, and a text whose narrative argues against the deterministic forces of society born from a lack of utility-based individualism.

End Notes

[1] John Stuart Mill, Utilitarianism (South Kitchener, Ontario: Batoche Books, 2001), 11-12.

[2] John Stuart Mill, On Liberty (South Kitchener, Ontario: Batoche Books, 2001), 54-55.

[3] Nathan Sheppard, The Essays of ‘George Eliot’ (New York: FUNK & WAGNALLS, 2009), 202-203. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/28289/28289-h/28289-h.htm

[4] George Eliot, Middlemarch (Oxford, UK: Oxford World Classics, 2019), 3.

[5] Eliot, Middlemarch, 3-4.

[6] Eliot, Middlemarch, 26-27.

[7] Darrell Mansell Jr., “Ruskin and George Eliot’s ‘Realism,’” Criticism 7, no. 3 (1965): 205-206.

[8] Eliot, Middlemarch, 205.

[9] Eliot, Middlemarch, 464.

[10] Eliot, Middlemarch, 505.

[11] Eliot, Middlemarch, 741.

[12] Eliot, Middlemarch, 3.

[13] Eliot, Middlemarch, 782-783.

[14] Eliot, Middlemarch, 784-785.

Spencer Dittelman

Spencer Dittelman is a member of the class of 2026 at the University of Rochester where he is a double major in British and American Literature, and Politics, Philosophy, and Economics. He is a student and hopeful scholar of Victorian literature whose work won the 2024 Charles Miller Williams and Mary Washington Williams Memorial Prize at the University of Rochester. Much of his research lies at the intersection between literature and intellectual thought and he hopes to pursue a PhD in this area of study.