From Angst to Ashes: The Complexities of Addiction in the Lives of Kurt Cobain and Layne Staley, 1987-2002

In the rain-soaked streets of 1990s Seattle, a seismic shift was brewing. The pulsating guitars and angst-ridden lyrics of grunge did not just define a genre; they became the battle cry of a generation hungry for authenticity. Nirvana, Alice in Chains, Pearl Jam, and Soundgarden emerged as icons, their raw sound echoing the disillusionment and alienation felt by millions. Yet, amidst this musical revolution lurked a shadowy presence: drug culture. It was not just a backdrop but was a central character in the drama, weaving its treacherous tendrils into the lives and music of the era’s luminaries. The pervasive influence of drugs left its mark on artistic expression and individual destinies, notably on figures like Kurt Cobain of Nirvana and Layne Staley of Alice in Chains. These substances cut lives short, tore families apart, and prematurely extinguished promising talents. Their complex relationship with drugs defies simplistic labels like “junkies.” They experienced moments of highs and lows, advocated for and condemned drug use, and ultimately succumbed to their addictions. This analysis of Cobain’s and Staley’s attitudes towards drugs throughout their careers, as reflected in their lyrical explorations, Rolling Stone articles, and shifts in public statements, highlights the interplay between creativity, fame, and addiction in music culture.

"Your Love is My Drug" by kevin dooley is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

The study of grunge music and its intersection with drug culture has evolved over time, shaped by changing scholarly frameworks. Grunge, emerging in the late 1980s, was distinct from punk in both musical style and cultural outlook. Musically, Grunge blended punk's rawness with metal's heaviness but incorporated slower tempos and a more introspective tone. Lyrically, grunge conveyed themes of disillusionment, alienation, and existential crisis, in contrast to punk's political defiance. Fashion-wise, grunge rejected punk’s DIY aesthetic in favor of a more slovenly, anti-fashion style—flannel shirts, torn jeans, and unkempt appearances—as a rejection of consumerism and societal norms. This attitude of disillusionment became central to the grunge ethos, reflecting broader generational frustrations and contributing to its association with drug culture and nihilistic trends in the early 1990s.

Music historians initially overlooked grunge within the broader landscape of music history. However, by the late 20th and early 21st centuries, scholarly interest in the genre grew substantially, culminating in a rich and diverse body of literature that seeks to unravel the complexities of grunge’s origins, evolution, and cultural significance. Early studies, such as law professor Perry Grossman’s 1996 article “Identity Crisis: The Dialectics of Rock, Punk, and Grunge,” laid the foundation for understanding grunge within the broader context of punk rock.[1] Grossman’s argument, which posited grunge as a continuation of punk’s rebellious ethos, sparked considerable scholarly debate. While some scholars supported Grossman’s perspective, suggesting that grunge maintained the spirit of defiance inherent in punk, others, like English professor Scott Stalcup in “Noise Noise Noise: Punk Rock’s History Since 1965” in 2001, contended that grunge’s focus on commercial success diverged from punk’s countercultural origins.[2] Offering a more nuanced perspective, music professor Mark Mazullo’s examination of Cobain in “The Man Whom the World Sold: Kurt Cobain, Rock’s Progressive Aesthetic, and the Challenges of Authenticity” in 2000, highlighted the eclectic influences shaping Nirvana’s music, including punk, pop rock, and hard rock.[3] These early studies predominantly focus on uncovering grunge's sound origins rather than deeper cultural elements.

Recent works on grunge music adopt a broad approach to analyzing the scene, aiming to address multiple facets such as its origins, the role of drugs within it, the characteristics of grunge, and with a particular focus on Nirvana. Stuart Kallen’s The History of Alternative Rock from 2012 exemplifies this trend, discussing the influence of grunge, its association with drug culture, and its impact on music, with significant attention paid to Nirvana.[4] Similarly, Vanessa Oswald’s Indie Rock: Finding an Independent Voice from 2018 and Justin Henderson’s 2021 book Grunge Seattle follow suit, offering comprehensive examinations of grunge that encompass its various dimensions, including its connection to drug culture, while also spotlighting the prominence of Nirvana within the genre.[5] These works, while comprehensive, do not offer significant new insights due to their broad scope, lacking the depth of earlier works from the late 1990s to early 2000s. Authors from the 1990s to the early 2000s did not prioritize catering to a general audience, whereas more modern works tend to do so. While this shift benefits by reaching a wider audience, it also restricts a deeper exploration of specific facets of grunge history and culture.

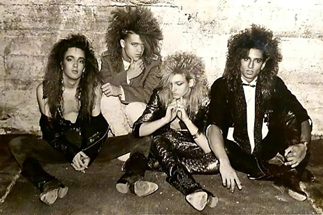

Cobain And Staley Grunge Icons

Existing research extensively explores grunge music’s cultural impact, but a significant gap remains: understanding the substance abuse patterns of Cobain and Staley. While some studies acknowledge their substance abuse, there is a lack of study into the progression and complexities of their drug consumption. Extant portrayals frequently oversimplify Cobain’s struggles and entirely neglect Staley’s journey. Notably, journalist David De-Sola’s 2015 book Alice in Chains: The Untold Story stands as the sole comprehensive work on Staley, leaving ample room for alternative perspectives on his life, particularly concerning drug use.[6]

So, why focus on Kurt Cobain and Layne Staley amidst the numerous artists of the grunge era? Their significance extends beyond their musical contributions; they epitomize the intertwined relationship between the grunge movement and drug culture. Through Nirvana’s monumental impact on global music and Alice in Chains’ enduring influence, Cobain and Staley became emblematic figures of their time. Their tragic deaths due to drug-related issues not only set them apart from other thriving grunge artists but also underscore the pervasive impact of substance abuse within the grunge scene. Delving into their lives uncovers not just personal tragedies but also pivotal moments that shaped the post-grunge rock era, prompting a deeper examination of the interplay between creativity, fame, and addiction in music culture.

The rock and roll scene had a longstanding history of intertwining with drugs, creating a narrative of influence and tragedy that predates the 1990s grunge era. The roots of rock and roll emerged from a fusion of blues, rhythm and blues, gospel, and country music in the mid-20th century.[7] This eclectic blend birthed a new sound that resonated deeply with the youth culture of its time, challenging societal norms and embracing themes of rebellion, freedom, and individuality. In its early days, during the 1950s, rock and roll emerged as a raw and unfiltered expression of the youth’s discontent with the status quo. Artists like Chuck Berry, Little Richard, and Elvis Presley electrified audiences with their energetic performances and rebellious attitudes.[8] Yet, amidst the euphoria of this musical revolution, a darker undercurrent lurked. Drugs, particularly amphetamines and later, marijuana, began to seep into the rock and roll scene. These substances, initially used as stimulants to keep up with demanding touring schedules soon became embedded with the lifestyle of many musicians. Amphetamines, commonly known as “uppers,” provided a burst of energy and heightened alertness, allowing musicians to maintain grueling performance schedules. Artists often overlooked their addictive nature and side effects while pursuing musical success.

The 1960s marked a revolutionary era for rock and roll, characterized by its electrifying energy and rebellious spirit. With iconic bands like The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, and The Doors leading the charge, the music scene was ablaze with innovation and experimentation.[9] Alongside the cultural revolution came a pervasive presence of drugs, notably marijuana, LSD, and psychedelic substances. These mind-altering substances became fused with the rock and roll lifestyle, influencing both the music itself and the culture surrounding it. The dark side of drug use also cast a shadow, with tragic tales of addiction and overdose haunting the era.

In the 1970s, rock and roll evolved and diversified with genres ranging from hard rock and glam rock to punk and disco dominating the airwaves. Bands like Led Zeppelin, Pink Floyd, and Queen epitomized the larger-than-life rock star persona, delivering electrifying performances and pushing musical boundaries.[10] Moreover, the prevalence of drug use continued to play a significant role in the culture of the era, complementing the music scene. Cocaine became a drug of choice among many musicians and industry insiders, fueling late-night studio sessions and decadent partying. While drugs played a prominent role in shaping the rock and roll scene of the decade, they also contributed to its darker side, with stories of excess and tragedy haunting some of the era’s most influential figures in the late 1970s.

Elvis Presley stands as an iconic figure in the popularization of rock and roll, captivating audiences from the 1950s through the late 1970s with his mesmerizing stage presence and dynamic performances. Often acclaimed as the “King of Rock & Roll,” Presley revolutionized the music industry by blending rhythm and blues, country, and gospel into his signature style.[11] Unfortunately, behind the curtain, Presley grappled with personal struggles, notably his reliance on prescription medications. The pressures of fame, coupled with rigorous schedules and private challenges, led him into a spiral of dependency on drugs prescribed for various ailments. This dependence exacted a toll on his health, impacting both his physical appearance and mental well-being. Despite efforts to seek assistance and regain control of his life, Presley’s addiction ultimately played a role in his premature passing on August 16, 1977, at the age of 42.[12]

As the 1980s progressed, there was a shift in the landscape of rock and roll, characterized by a wave of new sounds and styles fueled by technological advancements and shifting cultural trends. From the rise of MTV and the emergence of synth-pop to the mainstream explosion of heavy metal and the underground punk scene, the music of the 1980s was as diverse as it was dynamic. Bands like U2, Duran Duran, and Guns N’ Roses dominated the charts, captivating audiences with their infectious melodies and larger-than-life personas. Nevertheless, amidst the glitz and glamor of the decade, the specter of drug use loomed large in the music industry. Cocaine remained pervasive, while newcomers like MDMA (ecstasy) found favor within music circles, contributing to a growing narrative of addiction and tragedy that echoed the woes of previous decades.[13]

The grunge movement’s emergence in the early 1990s not only brought about a sonic revolution but also challenged the prevailing norms of the music industry. Rejecting the glitz and glamor often associated with mainstream rock, grunge bands opted for a stripped-down aesthetic that mirrored the gritty reality of their surroundings. National superstars like Mudhoney, Pearl Jam, Mother Love Bone, Soundgarden, Nirvana, and Alice in Chains emerged from the rainy streets of Seattle, crafting lyrics that delved into the struggles of everyday life, touching upon themes of isolation, angst, and societal unrest.[14] This timing and location were crucial; the early 1990s were a time of societal flux, marked by economic uncertainty and a growing sense of disillusionment among young people.[15] Seattle, with its gritty, industrial landscapes and vibrant underground music scene, provided the perfect backdrop for grunge’s raw and authentic expression. The do-it-yourself ethos of the grunge scene allowed bands to bypass traditional industry gatekeepers, connecting directly with their audience and resonating far beyond the Pacific Northwest. However, beneath the surface of grunge’s authenticity lay a reality of substance abuse, with heroin emerging as a pervasive vice within the scene. While heroin use existed to some extent in the 1980s and even portions of the 1970s, the grunge scene distinctly characterized itself as “the first to be using heroin as a collective.”[16] This destructive drug claimed the lives of several influential figures in grunge, casting a shadow over the movement’s rapid ascent. Sadly, Andrew Wood of Mother Love Bone, John Baker Sanders of Mad Season, Jonathan Melvoin of The Screaming Trees, Kristen Pfaff of Hole, Shannon Hoon of Blind Melon, and, of course, Cobain and Staley succumbed to heroin’s grip.

As scholarly interest in grunge matured, researchers delved deeper into its cultural, social, and drug-related dimensions. Paul Friedlander and Peter Miller’s 2006 book, Rock & Roll: A Social History, built upon earlier studies, particularly focusing on the prevalence of drug use within the grunge community.[17] Their exploration revealed the intricate relationship between music, youth culture, and substance abuse, although the authors primarily tailored the book for a general audience. Kyle Anderson’s 2007 book Accidental Revolution: The Story of Grunge shared a similar focus, targeting a general audience and exploring the social aspects of the grunge era while offering only a superficial discussion of drugs within the scene.[18] Subsequent works by music professors Vincent Novara and Stephen Henry, such as A Guide to Essential American Indie Rock in 2009, and by drug researchers Humberto Fernandez and Therissa Libby, such as Heroin: Its History, Pharmacology, and Treatment in 2011, continued to shed light on the grunge music scene.[19] These works provided valuable insights into the motivations for drug use and its impact within the grunge community, overall offering a more comprehensive examination of how drugs become intertwined with the grunge era and the effects they have on the community.

"Closeup of glittery shimmery shiny pills capsule background" by Rawpixel Ltd is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Cobain And The Drug Muse

Heroin's devastating impact on the grunge community was tragically evident, particularly in the life of Kurt Cobain, one of its most iconic figures. Challenges marked Cobain’s upbringing, including his parents’ early divorce, which plunged him into a world of isolation and instability. Amidst this chaos, music and drugs emerged as Cobain’s sanctuary. Immersing himself in the vibrant punk rock scene, Cobain honed his skills as both a guitarist and a lyricist. Despite the turbulence in Cobain’s personal life, his artistic spirit thrived, with his music becoming a canvas for his innermost struggles. In 1987, Cobain co-founded Nirvana alongside bassist Krist Novoselic, later joined by drummer Dave Grohl.[20] However, Cobain’s rise to prominence in the music industry with Nirvana coincided with a darker descent into substance abuse.

In one of Nirvana’s early interviews with Hanmi Hubbard for the Current, Green River Community College’s student newspaper, titled “Hanging with Nirvana at Kurt’s House,” on April 22, 1989, Cobain offered an intriguing perspective on drugs.[21] He stated, “None of us do drugs. Krist and I are starting to drink again — if we drink two nights in a row, it’s a binge.”[22] Additionally, Cobain clarified, “We’re pretty much — we’re not anti-drug, we just choose not to do it.”[23] This sentiment echoed deeply in Nirvana’s debut album, Bleach, released two months later on June 15.[24] The song “Scoff” from this album mentions alcohol with the repeated line “Gimme back my alcohol,” yet Cobain had not ventured into hard drugs up to 1989.[25]

As Nirvana’s popularity surged in 1991 and 1992, Cobain found himself increasingly entangled in the world of drugs. This was particularly evident in Nirvana’s second album, Nevermind, released on September 24, 1991.[26] The album’s fifth track, “Lithium,” metaphorically delved into the mood-stabilizing drug lithium, often prescribed for bipolar disorder.[27] Another track from Nevermind, “On a Plain,” stands out as one of Cobain’s most straightforward references to drug use, with lyrics like “I got so high I scratched till I bled.”[28] A few months later, a Rolling Stone article dated April 16, 1992, titled “Nirvana: Inside the Heart and Mind of Kurt Cobain,” brought Cobain’s struggles with drug addiction to a wide audience.[29] The article depicted Cobain as “strikingly gaunt and frail” due to ongoing health issues exacerbated by stress and increased substance use.[30] Cobain expressed a longing for a respite to restore his well-being: “All I need is a break and my stress will be over with. I’m going to get healthy and start over.”[31] Despite this, Cobain’s stance on drugs remained somewhat ambivalent. He acknowledged their detrimental effects: “All drugs are a waste of time. They destroy your memory and your self-respect and everything that goes along with your self-esteem. They make you feel good for a little while, and then they destroy you. They’re no good at all.”[32] Despite his personal views, Cobain refrained from overtly condemning drug use, recognizing it as a personal choice. Cobain concluded, “I’m not going to go around preaching against it. It’s your choice, but in my experience, I’ve found they’re a waste of time.”[33] Even though Cobain was actively using drugs in early 1992, he maintained his belief that they were ultimately futile.

Nirvana’s third album Incesticide,[34] released on December 15, 1992, delved into themes of addiction, whether to substances or to intimate relationships, as evident in its final track “Aneurysm.”[35] The lyrics “Love you so much it makes me sick, come on over and shoot the shit” could imply either a toxic relationship with a partner or a destructive reliance on drugs.[36] A month later, at a joint concert in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil on January 22, 1993, featuring Nirvana and Alice in Chains headlining together for the only time, Cobain made a significant statement that highlighted his shift in perspective on drug use. In an interview with John Ruskin, better known as “Nardwuar,” a quirky Canadian interviewer famed for uncovering celebrities’ hidden depths, Cobain casually revealed, “I shot coke with Alice in Chains all night.”[37] Cobain's viewpoint on drugs as a futile pursuit appeared to lack conviction. Nirvana’s subsequent and final studio album In Utero,[38] released on September 21, 1993, further explored the theme of drug use. In the song “Dumb,” Cobain’s lyrics “Help me inhale and mend it with you, we’ll float around and hang out on clouds, then we’ll come down and have a hangover,” depict the transient euphoria of drug use followed by the inevitable crash, symbolized by the hangover, illustrating the cyclic nature of substance abuse.[39]

It is crucial to note that Cobain’s lyrics are often cryptic and open to interpretation, employing obscure language that requires careful consideration to decipher the themes of drug use woven throughout his music. Cobain himself reinforced this idea in a 1993 interview with MuchMusic shortly after the release of In Utero, where he stated, “People expect more of a thematic angle with our music; they always want to read into it. Before, I was just using pieces of poetry and garbage, you know, stuff that would spew out of me at the time. A lot of the time, when I write lyrics, it’s at the last second because I’m really lazy. Then I find myself having to come up with an explanation.”[40] This sheds light on the complexity of Cobain’s songwriting process and the layers of meaning that can be discovered upon closer examination of his lyrics.

Spiraling Into Destruction

As 1994 arrived, Cobain found himself entangled in a tumultuous relationship with drugs, one that exerted significant control over his life. In Rolling Stone’s January 27, 1994, article titled “Kurt Cobain: Success Doesn’t Suck,” an explanation regarding Cobain’s drug use emerged.[41] He confessed to his ongoing heroin addiction but framed it as a coping mechanism for his chronic stomach pain. Cobain expressed, “I would give up everything to have good health, honestly,” while stressing that he had stopped using heroin by early 1994.[42] This marked a significant shift in Cobain’s relationship with drugs, moving away from his earlier dismissal of them as a waste to acknowledging their destructive impact and his growing dependence on them. Within the same publication, Cobain reflected on how his drug use affected his relationships, particularly within the band. He admitted, “When I was doing drugs, it was pretty bad. There was no communication. Krist and Dave, they didn’t understand the drug problem.”[43]

In March 1994, during a European tour, Cobain’s declining health became increasingly noticeable. His onstage presence became inconsistent, as seen in concert footage where his vocal performance suffered, and he appeared disconnected from the audience. The culmination of his struggle occurred during Nirvana’s last show in Munich, Germany, on March 1. Just two days later, on March 3, 1994, in Rome, Cobain experienced a severe overdose after taking Rohypnol, a powerful sedative drug. This overdose led to the cancellation of the remaining tour dates, underscoring the impact of Cobain’s addiction on his personal life and band commitments. Barely a month later, on April 5, 1994, Cobain’s life ended tragically when he was found dead at his home from a self-inflicted gunshot wound. A Rolling Stone article titled “Kurt Cobain’s Downward Spiral: The Last Days of Nirvana’s Leader,” published on June 2, 1994, revealed that Cobain had a high concentration of heroin in his bloodstream as well as heroin paraphernalia found next to his body.

Cobain’s journey, from a tumultuous childhood to his rise to fame with Nirvana, stands as a testament to the intricate dance between artistic brilliance and personal tribulations. His public statements about drugs reveal a tapestry of contradictions and inner conflicts, highlighting the stark contrast between his disdain for drugs and his ongoing battle with addiction. Cobain’s candid admissions and justifications, interspersed with moments of clarity and remorse, illuminate the intricate path he traversed. In his later-published personal journals from 2002, Cobain humorously articulated his belief that “Live music is the most primal form of energy release you can share with other people, besides having sex or taking drugs.”[44] This philosophy not only humanizes the grunge era but also accentuates Cobain’s lasting influence as an artist who sought to forge connections through music, leaving behind a legacy that transcends his personal struggles.

The Struggle Of Alice In Chains’ Staley

As the grunge movement rippled through the music scene, it not only gave rise to iconic artists like Cobain but also provided a backdrop for another figure whose life echoed the ethos of struggle and introspection emblematic of that era. Layne Thomas Staley, born on August 22, 1967, in Kirkland, Washington, faced challenges in his early years. His parents’ divorce during his childhood deeply impacted him, contributing to feelings of instability and self-reflection.[45] Immersing himself in the Seattle music scene, music became Staley’s refuge, providing expression for his inner turmoil. In 1987, Staley co-founded the band Alice in Chains, which gained recognition for its unique fusion of grunge and metal elements.[46]

Before Alice in Chains achieved commercial success, Staley battled addiction. During his teenage years, preceding the formation of Alice in Chains, Staley experimented with substances like LSD and psychedelics. These encounters not only shaped his initial perceptions of reality but also set the stage for his subsequent battles with addiction. In Alice in Chains’ debut album Facelift, released on August 28, 1990, the closing track titled “Real Thing” stands as the sole drug reference, alluding to Staley’s early drug use with lyrics like, “I grew up, went into rehab, you know the doctors never did me no good. They said, ‘Son, you’re gonna be a new man.’ I said, ‘Thank you very much and can I borrow 50 bucks?’”[47] This verse not only revealed Staley’s early struggle with addiction but also humorously critiqued the effectiveness of rehab, a sentiment that later haunted Staley.

Although Staley previously used substances before joining Alice in Chains, it was the release of their second album Dirt on September 29, 1992, that solidified his changing attitude towards hard drugs.[48] The lyrics of Dirt were starkly direct, presenting a narrative-rich in grim truths about drug dependency. The album’s seventh track, “Junkhead,” dug deeply into drug themes, as indicated by its title.[49] For instance, Staley expressed, “A good night, the best in a long time. A new friend turned me onto an old favorite; nothing better than a dealer who’s high, be high and convince them to buy.”[50] He further mused on drug preferences with, “What’s my drug of choice? Well, what have you got? I don’t go broke and I do it a lot.”[51] The song also satirized academia: “But we are an elite race of our own, the stoners, junkies, and freaks. You can’t understand a user’s mind, but try with your books and your degrees.”[52] Staley challenged conventional understanding, suggesting that those who immerse themselves in drugs share a unique perspective that defies scholarly analysis. “God Smack” continued the thematic exploration of drug use with lines like “Stick your arm for some real fun” and the cautionary “Can’t get high or you will die.”[53] In “Hate to Feel,” the album’s eleventh track, Staley expressed personal struggles, referencing “pin cushion medicine” as a metaphor for drug injection and depicted the transition from curiosity to dependency.[54] The poignant line, “All this time, I swore I’d never be like my old man, what the hey, it’s time to face exactly what I am,” resonated deeply given Staley’s convulsive relationship with his father, who reentered his life only to indulge in drugs together after Staley achieved fame.[55]

A few months after the release of Dirt in November 1992, during an interview on Musique Plus, a French-Canadian television station promoting Alice in Chains’ Dirt tour, Staley openly discussed his drug use when questioned.[56] The interviewer probed, “When you have a problem with heroin, does it automatically make you think about death because you’re playing with your life?”[57] Staley stated: “Yeah, I suppose that comes with the territory. Flirting with death—that’s probably what’s most attractive about it at first, is the danger, you know? But I beat it, I beat death! I’m immortal!”[58] Staley’s commitment to quitting heroin after the release of Dirt remained consistent up to this point. In a November 1992 Rolling Stone article titled “Alice in Chains: Through the Looking Glass,” which delved into Staley’s personal battles, the band’s musical journey, their ascent to stardom, and their tour experience, Staley revealed that he nearly conquered his heroin addiction.[59] He asserted, “The facts are that I was shooting a lot of dope, and that’s nobody’s business but mine. I’m not shooting dope now, and I haven’t for a while... I took a long, hard walk through hell. I decided to stop because I was miserable doing it. The drug didn’t work for me anymore.”[60] Staley concluded, “In the beginning, I got high, and it felt great; by the end, it was strictly maintenance, like food I needed to survive. Since I quit doing it, I tried it a couple of times to see if I could recapture the feeling I once got off it, but I don’t. Nothing attracts me to it anymore. It was boring.”[61] The article also mentioned a show in Dallas, Texas, where Staley performed “God Smack” while “repeatedly jabbing his arm with the microphone, simulating a junkie’s needle.”[62] Although it seemed that Staley’s heroin addiction was over by 1992, it would not be long before he found himself struggling with it again.

The Hollywood Rock 1993 Rio, Brazil concert, during which Kurt Cobain mentioned, “I shot coke with Alice in Chains all night,” was notably more eventful for Alice in Chains than for Nirvana.[63] That evening, both Nirvana and Alice in Chains indulged in drug use together. The night took a dark turn when Alice in Chains’ bass player, Mike Starr, nearly succumbed to a drug overdose. Staley also showed signs of being in a troubled state himself, which the show highlighted through the noticeable strain in his voice, a rarity for him.[64] Such chaotic shows, like the one in Rio, became frequent occurrences, with Staley’s behavior growing increasingly erratic and unpredictable throughout 1993, an indication that his battle with heroin was far from over. By January 1994, Alice in Chains ceased performing live for a considerable period. Recently uncovered footage showed them at a sound check for an acoustic benefit for Norwood Fisher of Fishbone on January 7, 1994, which turned out to be their last show until 1996. Staley’s physical deterioration was evident, with him appearing emaciated, pale, and wearing gloves to conceal heroin injection marks on his hands.[65]

Later in 1994, Staley joined forces with Mike McCready of Pearl Jam, drummer Barrett Martin of Screaming Trees, and bassist John Baker Saunders to form a supergroup aimed at addressing their struggles with drug addiction. This initiative led to the formation of Mad Season, a band focused on sobriety and personal healing. Through his time in Mad Season, Staley’s perspective on drugs shifted drastically, recognizing their destructive nature rather than viewing them as acceptable. Their sole album, Above, released in March 1995, delved into the challenges of addiction, reflecting Staley’s own experiences.[66] The album’s opening track, “Wake Up,” darkly stated, “Slow suicide’s no way to go,” highlighting the gradual self-destruction inherent in addiction.[67] The band somberly acknowledged in the third song, “River of Deceit,” that “My pain is self-chosen” suggesting that the band members’ suffering stemmed from their own choices.[68] In “Artificial Red,” the fifth track, the lyrics delved into the struggles of rehab, questioning, “In the house of ill repute, is this the way I spend my days, in recovery of a fatal disease,” an illustration of the challenging journey of recovery from addiction.[69] Mad Season offered Staley and his bandmates a promising path to overcome addiction and rejuvenate their musical careers, while marking a potential turning point for Staley's relationship with hard drugs. Unfortunately, that hopeful scenario did not come to fruition for Staley.

In late March 1995 Alice in Chains reconvened in the studio to commence work on what ultimately marked their last full-length album featuring Staley. This self-titled album, Alice in Chains, underwent recording from April to August 1995, a process extending significantly longer than their previous records.[70] During this period, Staley's addiction resurfaced intensely, as highlighted in the Rolling Stone article “Alice in Chains: To Hell and Back,” often leading to delays or his absence from recording and rehearsal sessions.[71] Notably, several tracks on this album touch on drug use. The opening track “Grind” satirized the persistent speculation about Staley’s drug-related demise, cautioning, “In the darkest hole, you’d be well advised not to plan my funeral before the body dies.”[72] Moreover, the third track, “Sludge Factory,” explicitly mentioned drug-induced experiences: “Things go well, your eyes dilate, you shake and I’m high.”[73] Later, on December 12th, 1995, the band released “The Nona Tapes,” a mockumentary intended to promote Alice in Chains.[74] Staley made sporadic appearances in the film, exhibiting visible signs of drug use with a frail appearance and a detached demeanor even in social interactions.

Alice In Chains: To Hell And Back

A couple of months later, on February 8, 1996, Rolling Stone published an article titled “Alice in Chains: To Hell and Back,” that delved deeply into the darker side of fame: Staley’s drug addiction.[75] Staley expressed, “I wrote about drugs, and I didn’t think I was being unsafe or careless by writing about them. Here’s how my thinking pattern went: When I tried drugs, they were fucking great, and they worked for me for years, and now they’re turning against me — and now I’m walking through hell, and this sucks.” Expanding on this, Staley expressed, “I didn’t want my fans to think that heroin was cool. But then I’ve had fans come up to me and give me the thumbs up, telling me they’re high. That’s exactly what I didn’t want to happen.”[76] He continued, “If I sat here and said, ‘I’m 90-days sober and easy does it, stay the course,’ I’d be full of shit, because I’m not 90-days sober. But I’m not in the bathroom getting high, either. And two years ago I would have been. It’s not something I think about. It’s not something I wake up and have to go find.”[77] Staley’s reflection underscored the complex and often turbulent relationship between creativity, addiction, and the relentless pressures of fame.

By early 1996, Staley acknowledged that he had not achieved sobriety but felt that his addiction was not as intense as it had been in 1994. As the year progressed, Staley’s drug addiction continued to spiral. Alice in Chains participated in an unplugged concert on April 10, 1996, at the Brooklyn Academy of Music’s Majestic Theatre for the MTV Unplugged television series, marking their first live performance since January 1994. When Staley stepped onto the stage during the opening of “Nutshell,” the audience cheered, but they also could not overlook his visibly weakened state.[78] He appeared even thinner, wearing gloves to conceal track marks and sunglasses to mask the effects of drug use on his eyes, as he consumed a small amount of heroin before the performance. Later on, Alice in Chains appeared on two TV programs: the Saturday Night Special in California on April 20, 1996, and The Late Show with David Letterman in New York on May 10, 1996, to promote Alice in Chains.[79] They performed “Again” and “We Die Young,” marking their first stand-up rock-style performance since late 1993. During these appearances, Staley appeared stiff, clutching onto the microphone with evident disinterest in engaging with the show’s hosts.[80] It was apparent that Staley wanted to leave the stage as soon as the songs were over.

Surprisingly, Alice in Chains embarked on a mini-tour as the opening act for Kiss, featuring four shows from June 28 to July 3, 1996, kicking off at Tiger Stadium in Detroit. Recently uncovered footage from this show revealed Staley walking onto the stage, still frail and pale, and clutching the microphone tightly.[81] This footage is the last high-quality recording of Staley before his death. This Detroit show featured a notably poor but haunting vocal performance from Staley, with slurred words and the need to skip some songs to complete the set.[82] By the next show on June 30 at Freedom Hall in Louisville, Kentucky, Staley seemed to regain some vocal strength and was able to complete the entire set while also interacting with the crowd.[83] The third show, held on July 2 at Kiel Center in St. Louis, was similar to the previous ones, except Staley exhibited a glimpse of his former stage presence during the song “We Die Young,” moving around and singing energetically, reminiscent of his performances in the early 90s.[84] The final show of the tour took place at Kemper Arena in Kansas City on July 3. While Staley remained static at the mic throughout the performance, his vocal delivery was stronger compared to the previous shows, although still not reaching his peak from 1993.[85] During the crowd cam footage at the end of the Kansas City show, Staley and his bandmates lined up for one last bow, marking the end of an era for the group. Shortly after this show, Staley overdosed on heroin, requiring medical attention and underscoring the band’s inability to continue given Staley’s deteriorating condition.

Staley’s hopefulness in overcoming his drug addiction in 1992 had long faded. After the final show, his public appearances became rare. This absence coincided with the tragic loss of his ex-fiancée/girlfriend Demri Parrott, who had been intermittently with Staley since 1988 and passed away in October 1996 from a heroin overdose. This event marked a significant shift, an indication of Staley’s apparent resignation in his battle against addiction. Staley made a brief return to the spotlight at the 39th Annual Grammy Awards in early 1997. Still, he largely stayed out of the public eye until late 1998 when Alice in Chains reunited for their final studio session to record two last songs: “Get Born Again”[86] and “Died.”[87] The song “Died” carried profound emotional weight both musically and lyrically. Staley’s lyrics in the song, “I could climb up to where angels reside, ask around and find out where the junkies applied,” were a reference to Parrott, intensifying the song’s melancholy theme and the imagery of seeking solace among fellow addicts.[88] In “Died,” Staley’s voice carries a lisp due to tooth loss, symbolizing the toll of his addiction.[89] This song marked the sorrowful conclusion of Staley’s journey with Alice in Chains. A photograph from the studio session captured Staley, barely recognizable and wearing a crack pipe and possibly drug paraphernalia in his bag. This image serves as one of the last glimpses of Staley before his death.

On July 19, 1999, Staley called into the “Nothing Safe” Rockline interview alongside his bandmates to promote the band's compilation album Nothing Safe: Best of the Box[90]. Despite his overall happy and outgoing mood during the interview, Staley’s voice sounded frail and weakened, which raised concerns among fans and the media about his health.[91] Staley's appearance on the Rockline interview is one of the last public interactions he had before largely withdrawing from the public eye. From mid to late 1999 until 2002, Staley rarely ventured outside of his apartment. Locals who encountered Staley noted his frail appearance, weakness, and poor hygiene. Unfortunately, authorities found Staley dead inside his apartment on April 19, 2002, already in a state of decomposition. Subsequent investigation revealed that he had passed away on April 5, 2002, exactly eight years after Kurt Cobain’s death. Staley overdosed on a speedball, a deadly combination of heroin and cocaine, at the age of thirty-four. At the time of his death, Staley weighed just under ninety pounds, marking the tragic end of a long, sorrowful, and painful journey of drug abuse.

The harsh realities of drug use deeply impacted Staley’s life, a journey that began during his youth. At first, Staley approached drugs with a sense of optimism, experiencing what could be described as the “honeymoon phase,” where he felt invincible. His lyrics often delved into drug culture, capturing its allure and the lifestyle associated with it. As time progressed, Staley confronted the brutal truths of addiction—the relentless grip that slowly strips away an individual’s humanity. Despite making attempts to break free from drugs, Staley faced immense struggles. The tragic loss of his longtime soulmate, Demri Parrott, in late 1996 appeared to deepen his despair, pushing him to give up hope of overcoming addiction. Although Staley’s journey offers a cautionary tale for future generations, he expressed a desire for a different remembrance: “Every article I see is dope this, junkie that, whiskey this — that ain’t my title. Like ‘Hi, I’m Layne, nail biter,’ you know? My bad habits aren’t my title. My strengths and my talent are my title.”[92]

Both Kurt Cobain and Layne Staley’s experiences with drug use in the grunge music scene illustrated the destructive, dangerous, and deadly nature of drugs for individuals. Cobain’s career was relatively short, spanning seven years, and tragically, he passed away at the height of his fame. While his lyrics were not always straightforward, his contradictory public and media statements shed light on the complexity of Cobain’s relationship with drugs, revealing a journey that was far from a straightforward descent. Staley’s career, on the other hand, lasted nearly twice as long as Cobain’s, extending over ten years. Staley’s journey with drugs was also far from a linear decline. Staley’s lyrics were brutally honest, depicting drug use in stark terms as if it were a daily necessity. Initially, there were glimpses of hope in Staley’s media statements, but as time went on, his descent into deep addiction became evident. Both of these artists’ stories deserve careful consideration, listening, and understanding. They were not merely “junkies” but individuals grappling with real problems and facing real consequences, including broken families, a loss of young talents, and a lasting impact on millions of listeners who still engage with their music today. Their life stories serve as sobering reminders, showcasing the relentless grip of addiction and emphasizing the vital importance of seeking help, even in the darkest of moments. Even as the rock and roll genre evolves, the legacy of grunge continues to influence music and culture, making their experiences all the more relevant and impactful.

End Notes

[1] Perry Grossman, “Identity Crisis: The Dialectics of Rock, Punk, and Grunge,” Berkeley Journal of Sociology 41, (1996): 19–40, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41035517.

[2] Scott Stalcup, “Noise Noise Noise: Punk Rock’s History Since 1965,” Studies in Popular Culture 23, no. 3 (2001): 51–64, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23414589.

[3] Mark Mazullo, “The Man Whom the World Sold: Kurt Cobain, Rock’s Progressive Aesthetic, and the Challenges of Authenticity,” The Musical Quarterly 84, no. 4 (2000): 713–49, http://www.jstor.org/stable/742606.

[4] Stuart Kallen, The History of Alternative Rock (Detroit: Lucent Books, 2012).

[5] Vanessa Oswald, Indie Rock: Finding an Independent Voice (New York: Greenhaven Publishing, 2018); Justin Henderson, Grunge Seattle (Charleston, SC: History Press, 2021).

[6] David De Sola, Alice in Chains: The Untold Story (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2015).

[7] Friedlander and Miller, Social History, 20.

[8] Friedlander and Miller, Social History, 20.

[9] Kallen, History of Alternative Rock, 17.

[10] Kallen, History of Alternative Rock, 47.

[11] Friedlander and Miller, Social History, 20.

[12] Friedlander and Miller, Social History, 47.

[13] Friedlander and Miller, Social History, 298.

[14] Todd Kerstetter, “Rock Music and the New West, 1980–2010,” Western Historical Quarterly 43, no. 1 (2012): 64, https://doi.org/10.2307/westhistquar.43.1.0053.

[15] Kerstetter, “Rock Music and the New West,” 55.

[16] Anderson, Story of Grunge, 89.

[17] Paul Friedlander and Peter Miller, Rock & Roll: A Social History (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2006).

[18] Kyle Anderson, Accidental Revolution: The Story of Grunge (New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 2007).

[19] Vincent Novara, “A Guide to Essential American Indie Rock (1980-2005),” Notes 65, no. 4 (2009): 816–33, http://www.jstor.org/stable/27669942; Humberto Fernandez and Therissa Libby, Heroin: Its History, Pharmacology, and Treatment (Minnesota: Hazelden, 2011).

[20] Kallen, History of Alternative Rock, 70.

[21] Kurt Cobain, “Hanging with Nirvana at Kurt’s House in 1989,” interview by Hanmi Hubbard, Cobain on Cobain, April 22, 1989, https://medium.com/cuepoint/hanging-with-nirvana-at-kurt-s-house-in-1989-84eb0331ffc2.https://medium.com/cuepoint/hanging-with-nirvana-at-kurt-s-house-in-1989-84eb0331ffc2.

[22] Cobain, “Hanging with Nirvana.”

[23] Cobain, “Hanging with Nirvana.”

[24] Nirvana, Bleach, Sub Pop, 1989, compact disc.

[25] Nirvana, “Scoff,” track 8 on Bleach, Sub Pop, 1989, compact disc.

[26] Nirvana, Nevermind, DGC Records, 1991, compact disc.

[27] Nirvana, “Lithium,” track 5 on Nevermind, DGC Records, 1991, compact disc.

[28] Nirvana, “On a Plain,” track 11 on Nevermind, DGC Records, 1991, compact disc.

[29] Micheal Azerrad, “Nirvana: Inside the Heart and Mind of Kurt Cobain,” Rolling Stone, April 16, 1992, https://www.rollingstone.com/feature/nirvana-inside-the-heart-and-mind-of-kurt-cobain-103770/.

[30] Azerrad, “Heart and Mind of Kurt Cobain.”

[31] Azerrad, “Heart and Mind of Kurt Cobain.”

[32] Azerrad, “Heart and Mind of Kurt Cobain.”

[33] Azerrad, “Heart and Mind of Kurt Cobain.”

[34] Nirvana, Incesticide, DGC Records, 1992, compact disc.

[35] Nirvana, “Aneurysm,” track 15 on Incesticide, DGC Records, 1992, compact disc.

[36] Nirvana, “Aneurysm.”

[37] Tic Tac Tic Tac, “(RARE VIDEO) Kurt Cobain: "I Shot Coke with Alice In Chains All Night" [at the 1993 Hollywood Rock],” uploaded on June 25, 2017, Youtube video, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vHHH-3nu7xI.

[38] Nirvana, In Utero, DGC Records, 1993, compact disc.

[39] Nirvana, “Dumb,” track 6 on In Utero, DGC Records, 1993, compact disc.

[40] MUCH, “Much: Our Last Time w/ Kurt Cobain (1993),” uploaded on August 11, 2014, YouTube video, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PDgP4hN4OA4.

[41] David Fricke,“Kurt Cobain, The Rolling Stone Interview: Success Doesn’t Suck,” Rolling Stone, January 27, 1994, https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/kurt-cobain-the-rolling-stone-interview-success-doesnt-suck-97194/.

[42] Fricke, “Success Doesn’t Suck.”

[43] Fricke, “Success Doesn’t Suck.”

[44] Kurt Cobain, Journals (New York: Riverhead Books, 2002).

[45] Henderson, Grunge Seattle, 40.

[46] Henderson, Grunge Seattle, 34.

[47]Alice in Chains, Facelift, Columbia Records, 1990, compact disc; Alice in Chains, “Real Thing,” track 12 on Facelift, Columbia Records, 1990, compact disc.

[48] Alice in Chains, Dirt, Columbia Records, 1992, compact disc.

[49] Alice in Chains, “Junkhead,” track 7 on Dirt, Columbia Records, 1992, compact disc.

[50] Chains, “Junkhead.”

[51] Chains, “Junkhead.”

[52] Chains, “Junkhead.”

[53] Alice in Chains, “God Smack,” track 9 on Dirt, Columbia Records, 1992, compact disc.

[54] Alice in Chains, “Hate to Feel,” track 11 on Dirt, Columbia Records, 1992, compact disc.

[55] Chains, “Hate to Feel.”

[56] AliceinChainsPL, “Alice In Chains - Musique Plus French Canadian TV 11.92,” uploaded on Aug 4, 2007, Youtube video, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YhQ2aB2TVr0.

[57] AliceinChainsPL, “Musique.”

[58] AliceinChainsPL, “Musique.”

[59] Jeffrey Ressner, “Alice in Chains: Through the Looking Glass,” Rolling Stone, November 26, 1992, https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/alice-in-chains-through-the-looking-glass-244000/.

[60] Ressner, “Through the Looking Glass.”

[61] Ressner, “Through the Looking Glass.”

[62] Ressner, “Through the Looking Glass.”

[63] Tic Tac Tic Tac, “Cobain: "I Shot Coke with Alice.”

[64] Melissa Panek, “Alice in Chains live in Rio full concert January 22, 1993,” uploaded on Jul 15, 2011, Youtube video, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wSmWT8U-7qg.

[65] AltCopperpot5, “[New/Old] - Alice In Chains - 1994-01-07 - [Soundcheck] - Hollywood - Acoustic - (~8min of footage),” uploaded on Dec 24, 2022, Youtube video, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bx_zEDR4xa8&t=423s.

[66] Mad Season, Above, Columbia Records, 1995, compact disc.

[67] Mad Season, “Wake Up,” track 1 on Above, Columbia Records, 1995, compact disc.

[68] Mad Season, “River of Deceit,” track 3 on Above, Columbia Records, 1995, compact disc.

[69] Mad Season, “Artificial Red,” track 5 on Above, Columbia Records, 1995, compact disc.

[70] Alice in Chains, Alice in Chains, Columbia Records, 1995, compact disc.

[71] Jon Wiederhorn, “Alice in Chains: To Hell and Back,” Rolling Stone, February 8, 1996, https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/alice-in-chains-to-hell-and-back-244775/.

[72] Alice in Chains, “Grind,” track 1 on Alice in Chains, Columbia Records, 1995, compact disc.

[73] Alice in Chains, “Sludge Factory,” track 3 on Alice in Chains, Columbia Records, 1995, compact disc.

[74] Alice In Chains, “Alice In Chains - The Nona Tapes (Official Documentary),” uploaded on Jun 19, 2017, Youtube video, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v0Ohyj8FmLo.

[75] Wiederhorn, “To Hell and Back.”

[76] Wiederhorn, “To Hell and Back.”

[77] Wiederhorn, “To Hell and Back.”

[78] Alice in Chains, “Alice In Chains - Nutshell (MTV Unplugged - HD Video),” uploaded on Sep 28, 2018, Youtube video, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9EKi2E9dVY8.

[79] Onkel44lekno, “Alice In Chains - "Again", Saturday Night Special & "Again/We Die Young)", Letterman - 1996,” uploaded on May 10, 2013, Youtube video, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ssn9I47Tjd0.

[80] Onkel44lekno, “Alice In Chains - "Again", Saturday Night Special & "Again/We Die Young)", Letterman - 1996.”

[81] AltCopperpot5, “[New Footage/Partial] - Alice In Chains - 1996-06-28 - Tiger Stadium - [2-Songs: "Again" & "God Am"],” uploaded on Dec 19, 2022, Youtube video, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4joyxopbf1c.

[82] AltCopperpot5, “Alice In Chains - 1996-06-28 - Tiger Stadium.”

[83] Alice In Chains Fans, “Alice in Chains - Freedom Hall, Louisville, KY, Jun 30. 1996,” uploaded on Mar 19, 2015, Youtube video, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UfTog93p1tM.

[84] Alice In Chains Fans, “Alice in Chains - "We Die Young" Kiel Center, St. Louis, MO, Jul 2. 1996,” uploaded on Jan 31, 2015, Youtube video, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JJPe0Tt1kMI.

[85] Vitor Cortes, “Alice in Chains - Kemper Arena, Kansas, MO [07/03/1996],” uploaded on Nov 25, 2016, Youtube video, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IkcXEbQ_jJ8.

[86] Alice in Chains, “Get Born Again,” track 1 on Music Bank, Columbia Records, 1999, compact disc.

[87] Alice in Chains, “Died,” track 48 on Music Bank, Columbia Records, 1999, compact disc.

[88] Chains, “Died.”

[89] Chains, “Died.”

[90] Alice in Chains, Nothing Safe: Best of the Box, Columbia Studios, 1999, compact disc.

[91] Alice In Chains Fans, “Alice in Chains - "Nothing Safe" Rockline Interview, Jul 19. 1999,” uploaded on Mar 1, 2015, Youtube video, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P8w-r7ApfW0.

[92] Wiederhorn, “To Hell and Back.”

Kurtis Robbins

Kurtis Robbins is a senior at the University of Central Arkansas, pursuing a degree in Social Studies Education. Passionate about fostering a love for history, he aims to inspire high school students by connecting the past to the present. With a strong commitment to education, Robbins strives to cultivate critical thinking and a deeper understanding of the world in his future classroom. His goal is to empower the next generation with the knowledge and skills they need to engage meaningfully with society.