Misunderstood: A Cultural History of Eating Disorders in the West

By Meera Shanbhag

Over 30 million people in the United States are plagued by eating disorders, with at least one death related to eating disorders occurring every 62 minutes.[1] These serious illnesses, which have the greatest mortality rate of any psychological disorder, are characterized by abnormal eating patterns. Of all eating disorders, the two most well-known are anorexia nervosa, which consists of severe restriction in calories to achieve weight loss, and bulimia nervosa, in which purging follows periodic episodes of binge eating. While the diagnosis of the first eating disorder, “anorexia nervosa,” was not coined until 1873 by English physician William Gull, “disordered” eating behaviors as per current medical qualifications—most notably, self-induced starvation, binging, and purging—have a history that extends long before that. Although many assume that eating disorders have remained constant over time, reflecting unchanging diseases, evidence shows that past cases of disordered eating were not linked to body image and beauty standards of thinness until 1980. The cultural connotations in earlier time periods of the refusal of food, binging, and purging were distinctly different than they were following the creation of anorexia nervosa as a diagnosis, and both are unlike our understanding of eating disorders today.

English physician William Gull named the first eating disorder, anorexia nervosa, a disorder in his 1873 journal article, “Anorexia Hysteria (Apepsia Hysterica, Anorexia Hysterica).” A century later in 1979, the British psychiatrist Gerald Russell coined the diagnosis “bulimia nervosa,” characterizing it in his paper as “an ominous variant of anorexia nervosa.”[2] The year 1952 marked the creation of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), a handbook published and updated periodically by the American Psychiatric Association that contains the criteria used today to diagnose mental disorders in the US. The third version of the DSM, the DSM-III, released in 1980 listed “Anorexia Nervosa” and “Bulimia” as mental disorders in a section entitled, “Eating Disorders.” The DSM-III-R (1987), a revised version of the DSM-III, later modified the diagnosis “Bulimia” to “Bulimia Nervosa,” the name Russell gave the eating disorder in his 1979 paper, with the criteria of the disorder altered to make it more specific.[3] The current DSM-V manual continues to qualify anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa as eating disorders.

Today, the DSM-V, used to diagnose anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, lists the body image of the patient—for the former, a “disturbance in the way in which one’s body weight or shape is experienced,” and for both, a “self-evaluation [by the patient] that is unduly influenced by body weight and shape”—as part of the “diagnostic criteria” of both eating disorders.[4] The idea that a distorted body image, as shaped by cultural standards of beauty, could cause disordered eating patterns is entirely absent from many past accounts of these behaviors, particularly in the period before 1873, a time when eating disorders were not a disorder. In fact, the possibility that an individual could starve, binge, or purge intentionally to lose weight did not exist. This paper focuses narrowly on the characterization and perception of disordered eating behaviors—specifically, self-induced starvation, binging, and purging—in three periods: before 1873, a time when the medical community did not consider eating disorders an illness; between 1873 until 1980, when physicians and mental health experts created the diagnoses anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, which were viewed as mental illnesses of any psychogenic origin; and after 1980 to the present, when the DSM classified the two disorders, respectively, as a specific category of mental illness called “eating disorders” linked diagnostically with a disturbed body image, hereafter called “beauty image,” of the patient.

Accounts of disordered eating behaviors according to current qualifications exist as early as 450-350 BCE, when doctors often suggested use of purging as a medical treatment. This idea stemmed from the common belief during that time period in the Humoral Theory, which stated that the four humors of the body —blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile —had to be in balance in order for an individual to lead a healthy life free of illness. The Humoral Theory is thoroughly described in the Hippocratic Corpus, a collection of ancient Greek medical writings written around 400 BCE by various individuals whose identities are largely unknown. In the specific treatise called “On Ancient Medicine” that is part of the Hippocratic Corpus, the use of purging is suggested to clear “overflow of the bitter principle, which we call yellow bile.”[5] During this time period, far from there being a link of purging behaviors to beauty image, there was not even a notion that self-induced purging could be a disorder itself. It was, instead, a treatment.

The possibility that purging could indicate a disorder is also nonexistent in other historical accounts of individuals who exhibit behaviors that would match more closely bulimic diagnostic criteria today. In his biographical book The Lives of The Twelve Caesars, the Roman historian Suetonius, in 121 CE, describes the binging and purging tendencies of Emperors Claudius and Vitellius. According to Suetonius, Emperor Claudius would “thoroughly cram himself” with food,” after which a “feather was put down his throat, to make him throw up the contents of his stomach,” while Emperor Vitellius would “always [eat] three meals a day, sometimes four” that he followed up with a “custom” of “frequently vomiting.”[6] When describing both emperors, Suetonius does not focus on the disordered eating behaviors themselves. Instead, he emphasizes the general indulgence of the emperors by saying they are “chiefly addicted to the vices of luxury and cruelty,” which he views with disapproval.[7] There seemed to be an association during this time period of binging and purging with the wealthy, who were likely the only ones that could afford to engage in such eating behaviors. While the eating patterns of the emperors could satisfy criteria of bulimia diagnosis today, the cultural meaning— or “thick description,” as the renowned American cultural anthropologist Clifford Geertz would call it—surrounding purposeful binging and purging in that time period was entirely different, which led to an assumption that they were not a disorder but a status symbol representing the rich.[8]

Similar to binging and purging, self-induced starvation had an ascribed cultural meaning distinct from that in its association with anorexia nervosa today. While self-induced starvation in modern anorexic patients is associated with poor beauty image, many historical cases of this disordered eating behavior were linked to religion. The medieval Catholic saint, Catherine Benincasa of Siena (1347-80), has been the subject of modern discussions of anorexia nervosa for her extreme religious fasting.[9] Although Benincasa displayed symptoms of the disorder in her refusal to eat and significant weight loss, her letters show that her reasons for starvation were to encourage self-discipline and moderation, which she believed would help her soul become closer to God: “there is more perfection in renunciation than in possession…. he [man] ought to renounce and abandon [his ‘riches’] with holy desire, and not to place his chief affections upon them, but upon God alone.”[10] Benincasa even discouraged her friend whose fasting had caused her to become excessively skinny—a body that many anorexic patients would crave for—from continuing to fast, because she had lost the self-discipline that she was trying to attain through fasting. Voluntary self-induced starvation was a common religious and spiritual practice among religious women in the late Middle Ages and has been retrospectively termed by scholars as “anorexia mirabilis,” or “holy anorexia.” These women, like Catherine Benincasa of Siena, often believed that extreme fasting and ascetism imitated the torment of Jesus during crucifixion, and, in doing so, could purge them of sin, purify their body, and attain them salvation from God. Benincasa, indeed, begins each of her letters to others with an invocation to the crucifixion of Jesus—“In the Name of Jesus Christ crucified and of sweet Mary”—and, in one letter to Brother William of England, states that the “one's chief aim” through starvation “ought to be… to slay the will; [so] that it may seek and wish naught save to [nothing except to] follow Christ crucified, seeking the honour and glory of His Name, and the salvation of souls.”[11] While there are parallels between the behaviors of medieval saints like Benincasa and the eating disorder anorexia nervosa, none of them had the disorder because the cultural meaning ascribed to starvation in that time was different, related to religiosity rather than beauty image as it is today.

Following the Middle Ages, citizens of the Western world, between 1500-1700, began to challenge the Christian church and consider more scientific explanations behind worldly phenomenon. During this period, known as the Reformation and the Scientific Revolution, came what some now consider to be the first medical descriptions of anorexia nervosa. In Phthisiologia, or, A Treatise of Consumptions (1694), physician Richard Morton details the causes, symptoms, and treatments for diseases of “consumption,” and discusses seeing two unique cases for the first time: a girl who suffered from a reduced appetite and “a Skeleton [body] clad only with skin” but without any typical fevers or coughs accompanying those symptoms, and a 16-year-old boy who suffered from significant weight loss.[12] For both patients, however, Morton credited the starved state to “nervous,” or emotional, causes, naming the disorder causing their conditions “Nervous Atrophy, or Con[s]umption.”[13] In the case of the latter, he attributed the weight loss specifically to “[s]tu-dying too hard, and the Pa[ss]ions of his Mind,” and consequently, “advis’d him” as treatment “to abandon his Studies, to go into the Country Air, and to u[s]e Riding, and a Milk Diet… for a long time.”[14] The etiology that Morton gave and the treatments he prescribed for the inexplicable self-induced weight loss in the two patients suggests that physicians like him in that time period considered weight loss to be only a secondary symptom of a different disorder. The possibility of purposeful self-induced starvation for weight loss or beauty image, once again, did not seem to exist in that time.

The rise of scientific thought, as reflected in the first medical descriptions of anorexia nervosa by Morton, was nonetheless met with backlash from religious leaders, whose authority to explain natural occurrences and behavior was being undermined. Hence, in the nineteenth century, the link between starvation and religion present in the late Middle Ages resurged, though in a slightly different way. While medieval saints like Benincasa starved themselves to attain salvation from God on a personal level, many Victorian “fasting girls” in the nineteenth century pretended to starve themselves in order to give off an appearance of being divine, essentially claiming that they could survive without food. In one key historical case, the “Welsh-fasting girl” Sarah Jacobs (1857-1869) put on a façade of surviving without food or water for two years. Dr. Robert Fowler, a physician closely involved in monitoring and treating Jacobs, described her as “very much devoted to religious reading” since youth, which was likely the reason she began her pretense of fasting: to convince the public of her divine status.[15] Amazed by her apparent ability to survive without food, “hundreds” of “people came from all parts of the country to see Sarah,” leaving her with gifts from books and clothes to large sums of money.[16] Even the parents of Jacobs became convinced that “she was supernatural” and “would not… die like the[ir] other children” because “the Lord would provide for her in a supernatural way.”[17] However, emerging skepticism within the medical community led doctors to conduct a test in which nurses monitored the home of Jacobs to ensure she was not consuming food covertly. During this period, Jacobs, no longer able to sneak in food like earlier, became extremely thin and began having convulsions, indicating she was clearly malnourished. Nonetheless, she continuously declined food. Although she exhibited disordered eating behaviors to the public in her refusal of food during her feigned and actual starvation, those behaviors were not labeled a disorder. Instead, the secondary symptoms she experienced after excess weight loss led doctors to diagnose her with other disorders such as universal tactile Hyperaesthesia, which involves an excess sensitivity to stimuli all over the body, and hysterical epilepsy, which is characterized by idiopathic convulsions. None of the diagnoses that doctors gave Welsh referenced beauty image, a concept associated with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa diagnoses today. Though other Victorian girls made similar claims to surviving without food, the case of Jacobs is most famous because she was the only one who resisted intake of food until her death by starvation.

In addition to the fact that eating disorders were not a disorder during the era Jacobs lived, the view of an ideal body seemed to differ during that time. In the DSM-V, one of the three major criteria used to diagnose an individual with anorexia nervosa, besides a general disturbance in beauty image, is an “Intense fear of gaining weight or of becoming fat.”[18] While individuals with anorexia nervosa today starve themselves because they consider a thinner body to be more beautiful, an 1869 article written in the British Medical Journal a few days after the death of Jacobs, describes how Jacobs, “In appearance… was decidedly pretty” prior to her starved state for “having a plump, ruddy face.”[19] While the current DSM-V assumes that the desire of a patient to be skinny causes anorexia nervosa, this supposition is entirely absent from many past accounts of self-induced starvation, such as that of Benincasa and the Welsh fasting girl, an indication that definitions surrounding disordered eating behaviors are culturally grounded. In both cases, however, a poor beauty image or concern over beauty standards were not the cause of starvation behaviors.

The coining of anorexia nervosa as a diagnosis by Sir William Withey Gull, MD, occurred only a few years after the Sarah Jacobs died in December of 1869. While the Reformation and the Scientific Revolution laid the groundwork for scientific thought, the creation of the diagnosis of anorexia nervosa marked the beginning of a period after which medical explanations increasingly prevailed over religious explanations of behaviors like disordered eating patterns. In the paper Gull presented on “anorexia nervosa” in an address on October 24, 1873, he defined the condition as a “peculiar form of disease occurring mostly in young women… chiefly between the ages of 16 and 23” that is “characterised by extreme emaciation, and often referred to latent tubercle, and mesenteric disease.”[20] Though he initially termed this “disease” as “Apepsia Hysteria,” he changed the name to anorexia nervosa in this paper because “Anorexia,” or loss of appetite in Greek, “would be more correct,” and “nervosa” avoids confusion of the “disease” with hysteria.[21] Of utmost significance in this paper is his attribution of the etiology of the “disease” to “a morbid mental state” that “destroy[s] the appetite of the patient.”[22] For the first time, the behavior of self-induced starvation is considered a mental illness. However, the physician Gull does not consider either the desire of the patient for weight loss or a poor beauty image as the cause of their symptoms, perhaps because the view of a good-looking body during that time was “plump.”[23] This word was used to describe the face of Sarah Jacobs (1857-1869) when she was “decidedly pretty” before starving herself.[24] Hence, the cultural context surrounding distorted eating patterns, such as self-induced starvation, in the late 1800s is different than it is now, when anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa are eating disorders linked to a distorted beauty image.

Following the creation of anorexia nervosa as a diagnosis, the assumption that anorexia nervosa was a mental illness of psychogenic origin, without association to beauty image, is evident in other articles written in the early 1900s. The physician Henry B. Richardson, for instance, diagnosed six patients in 1939 who suffered extreme emaciation with no known physical causes as having anorexia nervosa because, “Anorexia nervosa is diagnosed by the demonstration of the neurosis.”[25] Many medical professionals searched for psychosomatic explanations for the refusal of food by patients with anorexia nervosa. In a 1937 paper called “Dreams in so-called endogenic magersucht (anorexia),” German physician Viktor Von Weizsäcker analyzed the dreams of patients during a restriction phase associated with anorexia nervosa and following periodic binges that he descriptively called “bulimia,” meaning excess appetite. He diagnosed the patients with only anorexia nervosa, though, since “bulimia nervosa” was not a disorder then. Ultimately, he found themes of “‘disembodiment… and death’” in the dreams of the patients immediately following their food restriction and binging, and he concluded from his investigation that their refusal of food was due to a “longing for death.”[26] The Canadian psychoanalyst W. Clifford M. Scott attributed the lack of appetite in young anorexic patients to “complex emotional problems,” such as “earliest anxiety situations of a paranoid type” and, in older women, to sexual mishaps earlier in life.[27] Neither of the physicians alluded to a desired weight loss of the patient or a distorted beauty image as a cause when searching for an etiology associated with anorexia nervosa.

The specification of self-induced starvation, binging, and purging from mental illnesses with any psychogenic origin to a mental illness caused by a disturbed beauty image is evident in the evolution of the DSM criteria for anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. In the first version of the DSM (1952), the terms “anorexia” and “bulimia” were listed as digestive symptoms meaning “loss of appetite” and “excessive appetite,” respectively.[28] The DSM-II (1968) qualified anorexia nervosa as a diagnosis of a “Feeding Disturbance” under a section called “Special Symptoms,” but it did not designate the disorder as an eating disorder linked to beauty image.[29] The DSM-III (1980) was the first edition in which the designation eating disorder appeared, and even though it included both “anorexia nervosa” and “bulimia,” only anorexia nervosa was associated with beauty image.[30] Seven years later, the link between bulimia and beauty image was made: a revised version of the DSM-III called the DSM-III-R altered the diagnosis “bulimia” to “bulimia nervosa” and added “Persistent over-concern with body shape and weight” as one of the four diagnostic criteria for the disorder [31]The DSM-III-R marked a critical turning point after which both anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa were qualified as a mental illness called “eating disorders” and associated with a disturbed beauty image. Therefore, historical accounts of disordered eating behaviors were not eating disorders as we define them today.

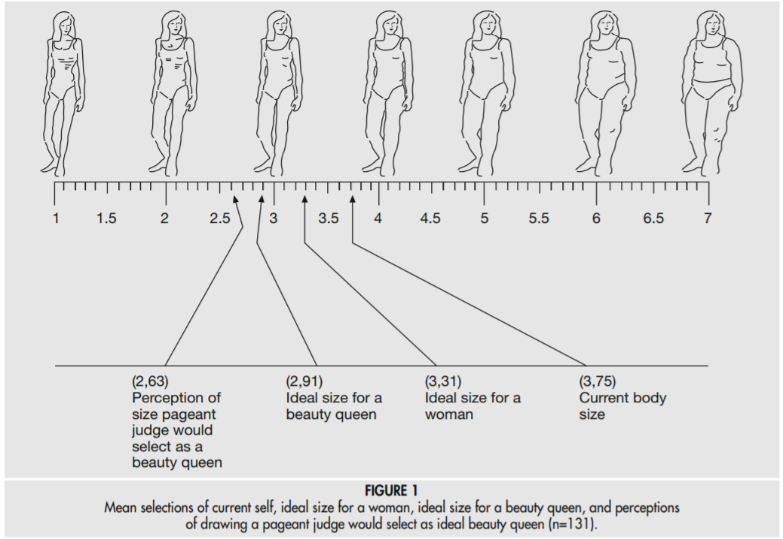

An examination of articles ranging from 1980, the approximate time when disordered eating behaviors shifted from being considered mental illnesses to a specific category of mental illnesses called eating disorders, to today shows how closely eating disorders —in particular, the most well-known anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa—were and continue to be linked to beauty image. In a newspaper article written in 1987, Vicky Cosstick, a facilitator of NGOs that focus on combating global issues from poverty to eating disorders, discusses the case of her friend, Judy. To Cosstick, Judy was a “typical anorexic” in that her “refusal to eat” arose out of a desire to “impress others” based on “her perceptions [that] their expectations of her” were to be skinny[32]. As she explains, Judy would “describ[e] other, normal women as revoltingly fat (including myself [Cosstick]).”[33] The distorted beauty image that can trigger many eating disorder patients, such as Judy, to engage in anorexic and bulimic behaviors today stems from a modern-day cultural assumption that a thin body is the ideal and, in some cases, the standard of beauty. An anonymous survey conducted in 2003 on 131 female beauty pageant contestants from 43 US states indicated that about half (48.5%) wanted to be thinner and 57% were attempting to lose weight. Furthermore, when provided a scale from 1-7 containing images of women with increasing body sizes, the contestants, on average, ranked their “current body size” the highest (3.75), followed by the “ideal size for a woman” (3.31) and the “perception of [the] size [a] pageant judge would select as a beauty queen” (2.63) (Figure 1).[34] Not only did the contestants themselves believe that the ideal body for a woman was thinner than their own, but they also believed that the public felt the same.

This cultural assumption is, additionally, visible in a famous poem called “Ellen West” that Frank Bidart, a Pulitzer-prize winning American poet, wrote in 1990. The poem is based on a case account by the psychiatrist who treated Ellen West, a pseudonym for a woman (1888-1921) who suffered from anorexia, bulimia, and possibly other psychotic illnesses before committing suicide at age 33. Written from the perspective of Ellen West, the poem describes the tension West feels between her cravings for food and her desire to remain thin, which she views as “ideal,” and her desire to “defeat [the] ‘Nature’” that makes her gain weight.[35] While the poem does accurately describe some facts in the case history and the feelings of Ellen West, it also incorporates Bidart’s interpretation of what he considered the beliefs of West. Ellen West clearly had a fear of becoming fat and a desire to have a thinner body. As she herself stated, “If there were a substance which contained nourishment in the most concentrated form and on which I would remain thin, then I would still be so glad to continue living.”[36] Bidart, nonetheless, assumes in this poem that part of her desire to be thin stems from the view of West that skinniness is “beautiful.”[37] In one part of the poem, West describes that when she sees a woman “with sharp, clear features, a good bone structure” indicating she is thin, “She was beautiful.”[38] While both Bidart and Ellen West considered a thin body to be the ideal, Bidart assumes that West believed thinness is associated with beauty, which he projects onto Ellen West in his poem. This assumption that Bidart makes about Ellen West’s beliefs in the poem goes to show the beauty standards of thinness that are an integral part of modern Western culture.

Overall, a historical analysis of disordered eating patterns from before the first century until now shows how greatly the cultural connotations of those behaviors changed across time periods. A single behavior, whether it be binging, purging, or starvation, received approval based on its association with concepts ranging from wealthy indulgence and religion to mental illnesses associated with beauty image. Before 1980, historical accounts do not suggest any etiological link between the three behaviors of starvation, binging, and purging and beauty image, the basis upon which they are grouped together as eating disorders today. The cultural context emphasizing beauty image that led to the creation of eating disorders as a diagnosis was absent from the past, which led to an assumption before 1980 that self-induced starvation, binging, and purging for purposeful weight loss did not exist. For this reason, the diagnoses eating disorders cannot be ascribed to patients in the past who exhibited “disordered” eating patterns by current medical qualifications.

The changing cultural connotations surrounding eating patterns like starvation, binging, and purging can inform the treatments we administer in a particular time period to individuals exhibiting those behaviors. Individuals with identical eating patterns were often treated differently in the past or, in some cases, not treated at all because those behaviors were considered “normal.” As the medical community gained primacy over the religious community during the late nineteenth century, however, more behaviors began to be labeled as “disorders” or “diseases,” especially with the creation of the DSM. The medicalization of behaviors such as self-induced starvation, binging, and purging as eating disorders implies a loss of agency, or a cause of conduct beyond the conscious individual self. While this implication may mitigate blame of the individual for their behaviors, it also permits treatments like force-feeding of patients with eating disorders today against their will, in what is considered the “best interest” of the patient. Whether or not we choose to label certain behaviors as a disorder can thus affect the types of interventions today that are considered ethical.

In the words of Harvard medical historian Charles Rosenberg, “Even those contemporary Western notions of disease specificity that seem to most of us somehow right and inevitable… are… socially constructed, like everything else in our culture.”[39] The well-known eating disorders, anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, are socially constructed, culturally influenced diagnoses, while, importantly, still real illnesses that take away lives every day. Anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa in the DSM-V currently used in US are associated with a poor beauty image and rest on the assumption that individuals strive for a thin body, though this etiology for self-induced starvation, binging, and purging and this standard of beauty, respectively, were not present across all time periods in the past. By extension, not all parts of the world today may have a poor beauty image as the most common cause of “disordered” eating patterns or a skinny body as the standard of beauty. The cultural history of eating disorders may lead us to contemplate the beauty standards we personally hold and perpetuate in our interactions, the cultural beliefs underlying our creation and explanations of diagnoses like eating disorders, and what behaviors we choose to label and treat as a disorder or disease.

[1] Eating disorder statistics. (2017). Retrieved from http://www.anad.org/education-and-awareness/about-eating-disorders/eating-disorders-statistics/

[2] Russell, G. (1979, August). Bulimia nervosa: an ominous variant of anorexia nervosa. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/482466.

[3] Plotkin, M. (2016, March 14). A brief history of eating disorders & binge eating disorder. Retrieved from https://bedaonline.com/a-brief-history-of-eating-disorders-binge-eating-disorder/

[4] American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing.

[5] Adams, F. (Trans.). (45n.d.). On Ancient Medicine. Retrieved from http://classics.mit.edu/Hippocrates/ancimed.mb.txt

[6] Tranquillus, G. S. (121 C.E). The Lives of the Twelve Caesars (T. Forester, Ed.; A. Thomas, Trans.). Retrieved from http://www.gutenberg.org/files/6400/6400-h/6400-h.htm#link2H_4_0006

[7] Tranquillus, G. S. (121 C.E.). The Lives of the Twelve Caesars (T. Forester, Ed.; A. Thomas, Trans.). Retrieved from http://www.gutenberg.org/files/6400/6400-h/6400-h.htm#link2H_4_0006

[8] Geertz, C. (1973). Thick Description: Toward an Interpretive Theory of Culture. The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays (pp. 3–30). Basic Books.

[9] Rudolph Belle, for example, retrospectively applies the diagnosis of anorexia nervosa to medieval saints like Benincasa in his book Holy Anorexia, while Caroline Walker Bynum, Holy Feast, Holy Fast, and Joan Jacobs Brumberg, Fasting Girls, argue against doing so.

[10] Benincasa, C. (2005, February). Letters of Catherine Benincasa (V. D. Scudder, Ed.; V. D. Scudder, Trans.). Retrieved from http://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/7403/pg7403-images.html

[11] Benincasa, C. (2005, February). Letters of Catherine Benincasa (V. D. Scudder, Ed.; V. D. Scudder, Trans.). Retrieved from http://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/7403/pg7403-images.html

[12] Morton, R. (1694). Phthisiologia, or, A Treatise of Consumptions. Retrieved from archive.org/stream/phthisiologiaort00mort#page/21/mode/2up

[13] Morton, R. (1694). Phthisiologia, or, A Treatise of Consumptions. Retrieved from archive.org/stream/phthisiologiaort00mort#page/21/mode/2up

[14] Morton, R. (1694). Phthisiologia, or, A Treatise of Consumptions. Retrieved from archive.org/stream/phthisiologiaort00mort#page/21/mode/2up

[15] Fowler, R. (1871). A complete history of the case of the Welsh fasting-girl (Sarah Jacob). Retrieved from archive.org/stream/b23982706#page/8/mode/2up

[16] Fowler, R. (1871). A complete history of the case of the Welsh fasting-girl (Sarah Jacob). Retrieved from archive.org/stream/b23982706#page/8/mode/2up

[17] Fowler, R. (1871). A complete history of the case of the Welsh fasting-girl (Sarah Jacob). Retrieved from archive.org/stream/b23982706#page/8/mode/2up

[18] American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

[19] The Welsh Fasting Girl. (1869). The British Medical Journal,2(469), 685-688. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/25218005

[20] Gull, W. W. (1997). V.-Anorexia Nervosa (Apepsia Hysterica, Anorexia Hysterica). Obesity Research, 5(5), 498-502. doi:10.1002/j.1550-8528.1997.tb00677.x

[21] Gull, W. W. (1997). V.-Anorexia Nervosa (Apepsia Hysterica, Anorexia Hysterica). Obesity Research, 5(5), 498-502. doi:10.1002/j.1550-8528.1997.tb00677.x

[22] Gull, W. W. (1997). V.-Anorexia Nervosa (Apepsia Hysterica, Anorexia Hysterica). Obesity Research, 5(5), 498-502. doi:10.1002/j.1550-8528.1997.tb00677.x

[23] The Welsh Fasting Girl. (1869). The British Medical Journal,2(469), 685-688. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/25218005

[24] The Welsh Fasting Girl. (1869). The British Medical Journal,2(469), 685-688. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/25218005

[25] Richardson, H. B. (1939). Simmonds Disease And Anorexia Nervosa. Archives of Internal Medicine, 63(1), 1. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1939.00180180011001

[26] Jackson, C. , Beumont, P. J., Thornton, C. and Lennerts, W. (1993), Dreams of death: Von Weizsäcker's dreams in so‐called endogenic anorexia: A research note. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 13: 329-332. doi:10.1002/1098-108X(199304)13:3<329::AID-EAT2260130312>3.0.CO;2-R

[27] Scott, W. M. (1948). Notes on the psychopathology of anorexia nervosa*. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 21(4), 241-247. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8341.1948.tb01174.x

[28] American Psychiatric Association. (1952). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (1st ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing.

[29] American Psychiatric Association. (1968). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing.

[30] American Psychiatric Association. (1980). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (3rd ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing.

[31] American Psychiatric Association. (1980). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (3rd ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing.

[32] Cosstick, V. (Summer 1978). Anorexia Nervosa. New Directions for Women, p. 9. Gale. Retrieved from http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/5K7721

[33] Cosstick, V. (Summer 1978). Anorexia Nervosa. New Directions for Women, p. 9. Gale. Retrieved from http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/5K7721

[34] Thompson, S. H., & Hammond, K. (2003). Beauty is as beauty does: Body image and self-esteem of pageant contestants. Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 8(3), 231-237. doi:10.1007/bf03325019

[35] Bidart, F. (1990). Ellen West. Retrieved from https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/48284/ellen-west

[36] May, R., Angel, E., & Ellenberger, H. F. (2004). Existence. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

[37] Bidart, F. (1990). Ellen West. Retrieved from https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/48284/ellen-west

[38] Bidart, F. (1990). Ellen West. Retrieved from https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/48284/ellen-west

[39] Rosenberg, C. E. (2003). What is disease?: In memory of Owsei Temkin. Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 77(3), 491-505. doi:10.1353/bhm.2003.0139

About the Author:

Meera Shanbhag recently graduated from Vanderbilt University in Nashville, TN with a Bachelor of Arts in Neuroscience and Medicine, Health, and Society, and a minor in Spanish. As an undergraduate, Meera was part of the College of Arts and Sciences Honors Scholars program. Through the program, she took an honors seminar called Cultural History of Disease with Dr. Arleen Tuchman that inspired her to research the cultural history of eating disorders. She hopes to pursue a career as a physician, with special interests in providing care to individuals with eating disorders and improving healthcare for disadvantaged populations.