The Black Janus

BY DIALLO SIMON-PONTE

I am a man of two faces. A question that we as humans all ask ourselves throughout the course of our lives is “Who am I?” The answer to that query is never concrete, but rather dynamic as it is always developing and changing as we navigate our way through the tempestuous hurricane that is life. For each person the answer will have its metaphysical variations based on the many intricate components that (make up who they are) or delineate their being. As I’ve journeyed through my four-year liberal arts education here at a predominantly white University, very sparingly I have been presented with the academic tools to introspectively examine myself within the framework of that question. Of my own accord, I began to explore masters of psychoanalytic theory Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung poring over their texts, only discovering that something innate was missing. Evidently, it was the incredibly important racial component that they unwittingly were leaving out. To explore the theme of self, I turned towards critical race theory, extrapolating everything I could from Black scholars Frantz Fanon, Aimé Césaire, Leopold Senghor, W.E.B. Dubois, and Ralph Ellison whereas they became my psychoanalysts. Further than “Who am I?” the questions quickly became “Who are We?” and “What are We in this white world?” all ideas that had been echoing in my head before I had even touched their literature. A quote that resonated with me early on was “everything changes especially when the “we” have to define themselves against a world which leaves no room for who and what they are because they are Black folks in a world where “universal” seems to naturally mean white.”[1] I was a student where the succinct nature of my immediate reality was that I attended a predominately white institution. My Blackness was posed against a sharp white background and very quickly into my collegiate experience I would find out what that truly meant. As a precursor, each person in this story will be identified based on their race whether or not it may seem superfluous to mention. The racial dynamics of this tale are imperative for complete comprehension.

[Freshman]

Dilution into the Universal

Freshman year, at any college, the underlying theme is all about fitting in. Becoming a part of something. Integrating within a scene, a culture, a society you can feel comfortable in. In hindsight, I merely enveloped myself in a cloak of naivete ignoring racist signals, signs, and undertones to feel a part of something I actually could never exist in.

To explain, the moment I stepped on campus I already had a scene, a culture, a society as I had just started my first year on the Division One Men’s Soccer Team. Athletically, it was a crucial time because life was about trying to impress. Impress your coaches and even more so your teammates as it’s they who spend your entire days with. You eat, you sleep, and you do everything together. There’s an initiation your peers put you through but also an initiation you put yourself through. An initiation almost of stripping yourself of things that make you in order to fit in with the whole [the entire]. For me being the only person of color on the team, that sacrifice involves more than just possibly altering the music you listen to, or the way you dress, or how you interact with girls because suddenly there is an athletic status quo you must adhere to. That sacrifice for me included stripping down my Blackness to where it became acceptable in a New England division one locker room because as Fanon points out “the Black man must not only be Black; he must be Black in relation to the white man.”[2] Out of necessity I split, I bisected, I morphed. My psyche transformed to imitate a Janus-like quandary: the Roman deity represented by a single head with a double face. That duality embodied the persona I now had to adopt. I had to be as Black as the locker room allowed me to be and I remember the first time my loyalties were really tested. The entire team was at a party one night and out onto the lawn behind the house spilled a large group of people. Of the congregation more than half the kids were Black whom I had briefly met in my short time at the University either from the culturally reciprocated head nod or in passing at the dining hall and the remainder of the students were a few of my teammates. The tempestuous nature of the situation was immediately noted in the fact one of the Black students was being aggressively held back by his friends. As an almost environmentally appointed liaison, I stepped up to see what the story was. The recap I got from the African -American faction was that one of the white juniors on my team had called one of the Black kids the n-word. Here that duality (the Janus effect) of who I now had to be identity-wise grabbed hold and shook me to my core. Why did I find myself walking over to my teammates to look for another perspective? Why when I heard the justification of “I didn’t call him a nigger, I called him a nigga” did I for the slightest of heart beats try to rationalize in my head why that might be acceptable? The subconscious and now tangible pressure that had been coolly simmering was now searingly hot. Césaire says there are two ways to lose oneself: walled segregation in the particular or dilution in the universal. I was drifting towards the latter.

It was not long after, the historically white Jesuit institution I attended reminded me of the thin line I walked on their campus. Nothing good ever happens at the University townhouses and the following incident only strengthens that sentiment. The universe or some higher pro Black powers that be, must have been at play one night because I felt an unexplainable force pull me away from a party my teammates were throwing. In the fifteen minutes I happened to leave and stop at a friend’s, a massive fight had broken out at the previous house involving some kids on my team and visitors. Later down the road, charges were pressed, and witnesses were called in by the Department of Public Safety to recount. When my team captain stepped away from the questioning, he approached me with a tinge of incredulity. “You won’t believe what they just asked me” he said. “After I had laid out everyone that was involved several times, they continued, ''Are you sure that Black kid on your team wasn’t there?”

All round me the white man, above the sky tears at its navel, the earth rasps under my feet, and there is a white song, a white song. All this whiteness that burns me… [3]

The police had been conditioned by the culture of the University to alleviate dangers to the white body and if that meant incriminating a minority student in the process, then so be it. I was very aware of where the value of my being stood that night in relation to my school. The weight, the burden was immense. That my life and future could be stripped away so effortlessly, caught up in a moment I had nothing to do with. The authority I had perceived was there to protect, was in fact at every waking moment vying to destroy me. Had I been at that party, I am sure that I would not be here now writing this paper.

[Sophomore]

Where Shall I Find Shelter from Now On?

A moment forever imprinted into my mind that acted as a catalyst for the change I began to undergo, happened the summer leading into my sophomore year. I was going through my camera roll showing my younger siblings the joy college parties would soon bring them. I stopped at one where I was dancing in a crowd of people who at the time, I perceived to be my friends. My twelve-year-old brother remarked, “You look like the token Black kid” and my heart hit the floor. He had meant it in a slightly pejorative joking manner, but a fog was lifted from my eyes and the façade began to crumble. Growing up, I had been conscious of my positionality in certain situations and social dynamics, always ensuring I removed myself from the labeling of the token. Yet here I was the oldest, being reminded by the youngest, that as a Black man you must always critically observe the scenes you involve yourself in. I had drifted too deep into the universal, and this snapped me out of a proverbial sunken place. Things began to become clearer and the direction I needed to follow began to appear before me. Sophomore year I decided to stop using my athletic time commitment as a deterrent for attending Black Student Union meetings. They were held once a week, every Sunday for about two hours and I wasn’t able to attend every single one, but I made a deliberate effort to go to as many as I could. I actually began to feel a part of something: a community that welcomed me forth for whoever I was and made no attempt to impose conformity. It was there I learned about the short history of the BSU and the fervent pushback from the University administration to oppose its creation a couple of years prior. In 2015, unarmed Michael Brown was gunned down by police in Ferguson, Missouri. In 2015, Freddie Gray was murdered in police custody. In 2015 faculty and administration were still having a hard time understanding why safe spaces for minority students on their campus were imperative to their health and well-being. The students fought hard and prevailed so in 2015 the Black Student Union was founded at the PWU. I learned that an institution that masquerades Black students on their highway billboards and yearly newsletters drafted new policies to derail the formation of the Club. Unheard pseudo-policies were created stating the Club’s constitution needed to be submitted to a University board for review, in an attempt to slow progress. Our Blackness was blatantly being policed at the very highest level. I was becoming aware of the school I was enrolled at, and I drew strength from those meetings seeing other Black students fight valiantly against the caustic white oppression.

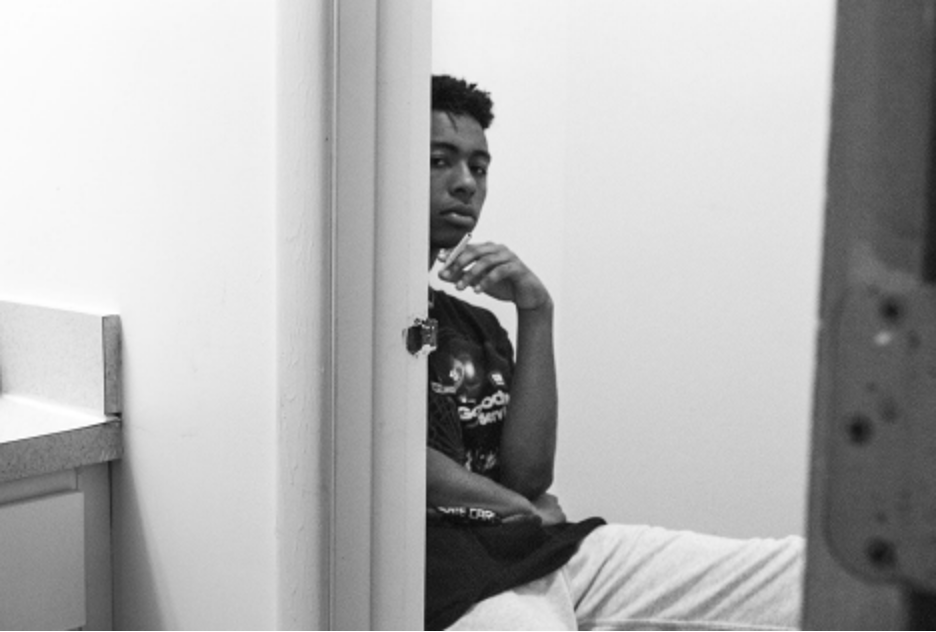

Sophomore year, I roomed with my white teammates but lived directly across from three Black students, which was comforting beyond measure; knowing I could step across the hall into a world where I was understood - where a dialogue of the feelings was able to be discussed. A space where the daily basis was able to be expressed because of a mutually shared foundation. A cultural context which meant cultural comprehension. That solace was warming; however, I was still far from being able to fully understand my emotions as well as properly navigate the social dynamics that existed outside of that hallway. There was one weekend in the Spring semester where my white roommates and I went to a party down the beach. When I arrived, I found the theme on that night was “white trash.” People were dressed in camouflage, dirty ripped white t-shirts, smeared in Black paint, had draped themselves in American flags, and written ‘Murica all over their bodies. I do not suppose my readers to be entirely ignorant of what demographic flocked to that party, so it seems rather irrelevant to elaborate. It is only now I’ve realized how ironically telling it is that a “white trash” themed party was scattered with American flags. At the time, I didn’t know how to feel being in that atmosphere. All I knew was the stigma associated with white trash is that it is pervasively racist. The entire time all I could think about was the lynching of Black people by Southern whites, this championing of a decrepit scandalous president, and all the piercing stares I was getting. Whether they were bitter looks or not, I couldn’t differentiate. I was mad. Should I have been mad? Was this party racially charged? Was I thinking properly? I tried to express this to the friends I arrived with, but they didn’t see the problem. I couldn’t process my feelings, so I locked myself in the bathroom and punched a hole in the wall. Never have I ever displayed anger in that fashion before. I didn’t know what was going on. I left that party soon thereafter with a million thoughts swirling in my head, but I couldn’t grasp one of them. I was trying to remember who I was but was having trouble coming up with a name.

A couple of weeks later I sat with two of my white female friends at the secondary Cafeteria on campus. It was a place I didn’t frequent often but they wanted to go there so I decided to submit to the consensus. My entire life I have repeatedly promised myself that I would never steal. That I would never adhere to the farcical common denominator stereotype that Black people are thieves. When tempted by peers in the past to go along with their antics I always firmly stood my ground with a definitive reluctance. Yet for some reason that day (if perhaps it was to impress the girls that I was with) nineteen years of consistent affirmations went out the window and I stole a plate of sushi. I hid the platter on one side of the exposed countertop, walked out of the line for the register, and five minutes later walked back to get it when a “Hey, what do you think you’re doing?” struck me in the back of the head. In unfamiliar territory, I froze. The worker behind the sushi station had seen me. I was caught and I was exposed. He approached me, a very visible anger in his eyes, and said, “I see you stealing in here all the time, give me that” and directed me towards the cashier. Fortunately, I was let off with a warning and walked away a dejected shell of myself, his words ringing in my ear. “I see you stealing in here all the time.” I rarely stepped foot into this Cafeteria, and not once had I stolen a single item from their inventory, yet still, he had associated me with a supposed consistent thievery. I had fallen right into the stereotype trap I had so vigorously fought against my whole life. I was forgetting who I was, and the anchoring oppression was sinking its teeth deeper into my psyche. Ravenous, it continued to claw its way into my being splitting my face into two without regard for anything in its path. I was bleeding profusely. And then I took an African American Art History course.

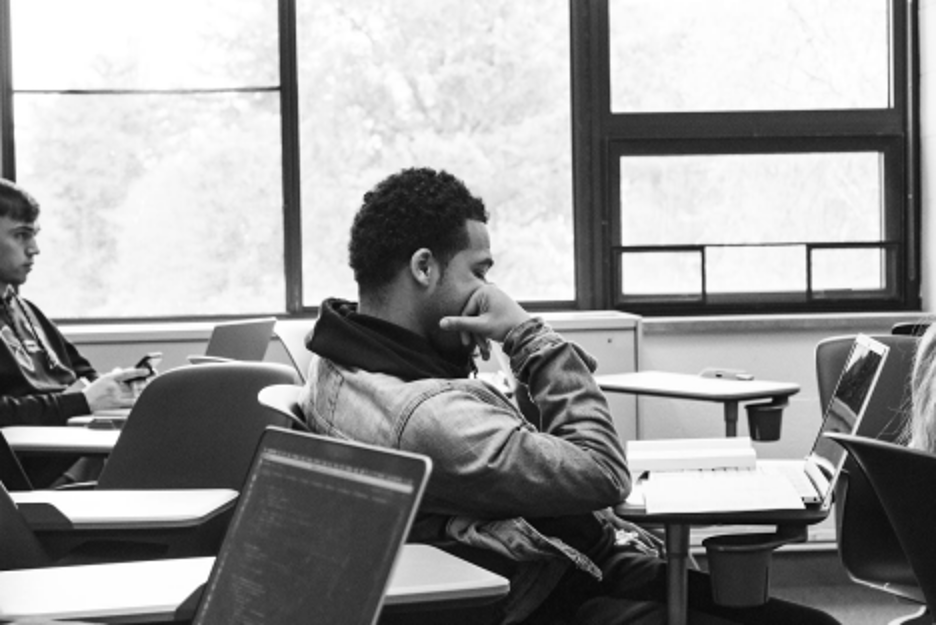

When a student, very infrequently I might add, learns about Art History throughout most American middle and high schools, it is largely focused on Europe’s contributions to the discipline, failing to encompass the full scope of artistic evolution and influences throughout the world. After a couple of introductory Art History classes during my freshman year, I realized that I had been deprived of an abundance of cultural and artistic expression. Therefore, Sophomore year, I enrolled in an African American Art History class to expand my knowledge on a topic I thought I knew a lot about. Growing up, my parents always said, “Know your history, so no one else can define it for you,” something that seemed to have slipped my mind in the past couple of months. They knew that our Black cultural heritage wasn’t going to be taught in the typical American classroom. So, at a young age, I set out to immerse myself in learning all that I could about African, African American, and Caribbean history. Prior to course enrollment, I presumptuously perceived that I had a good foundation on the subject matter from the museum exposure I had grown up with. I was soon to find out that I was so terribly wrong. On the first day, my professor posed the question “Who can name any African American artists?” Not a single person in the class of 30 could name one and neither could I. Dismayed, I sat incredibly still in my seat. Was the Art world something I’d completely skipped over in my youthful studies? I had prided myself on all that I thought I knew on African diasporic history only to realize that I had merely skimmed the surface of an ocean of information. We studied Barkley Hendricks, Bill Traylor, Carrie Mae Weems, Kara Walker, Jacob Lawrence, James Van der Zee, Gordon Parks, and the list went on and on. That class changed my life, and I cannot stress enough how important it was for a young Black man to see his own image reflected in something so masterful and beautiful. In the echo chamber of Euro-centric imagery and ideology that the Jesuit institution is, I was able to reclaim myself. I didn’t know it at the time but my submersion into Black American heritage “my way of living history within history, [this] history of a community whose experiences appear to be unique” was a metaphorical praxis of the core principles of Negritude.[4] Sitting in class I felt teleported into a new psychological geography. Yet every time the bell rang, I was expelled back into the surrounding ignorance, a rebirth of sadness that would only heal until next period.

In the dying weeks of my sophomore spring, I took my newfound learnings in stride, applying to be a member of the student body government Diversity & Inclusion board. I was inspired and a new intellectual energy, a new empowered intensity, and a newly enlightened heat raged within. Going into junior year I was going to repossess my own narrative for I was tired of not writing the plot.

[Junior]

The Black Man’s Burden

Junior year was a time when I felt like I was the spokesperson for the entire Black race in my locker room and I was. “I was responsible at the same time for my body, for my race, for my ancestors.”[5] I had successfully won the position on the Diversity & Inclusion board becoming a University-wide representative, which emboldened me to speak a bit louder in life. Even as a Freshman I had checked the usage of the n-word by my white teammates but now, as an established Junior I was fervent in my approach. Anytime I heard it uttered I locked it down. “Watch your fucking mouth. Why do you think you could say that?” An aggressive approach, something familiar in the toxic masculinity typical of a men’s locker room. My explanation when asked “Why can’t I” almost became robotic I heard that retort so often. “Words carry cultural context, and the n-word has been used by whites for hundreds of years to oppress Black people. Words bear weight, and through slavery, through lynchings, through the killing of my people that word has been used in alliance with that. I don’t care if you hear it in a song don’t fucking say it.” Some were receptive and from others I heard “Oh come on Diallo, I’m not racist my best friend from home is Black. My driveway is Black. I’m wearing Black clothes. I have a Black lab. My trash cans are Black. How could I be racist?” All meaningless responses, all insignificant replies, all missing the fucking point.

The white man wants the world; he wants it for himself alone. He finds himself predestined master of this world. He enslaves it. An acquisitive relation is established between the world and him. But there exist other values that fit only my forms. Like a magician, I robbed the white man of “a certain world,” forever after lost to him and his. When that happened, the white man must have been rocked backward by a force that he could not identify, so little used as he is to such reactions. Somewhere beyond the objective world of farms and banana trees and rubber trees, I had subtly brought the real world into being.[6]

Some were receptive. Too many were not. They’d agree with what I was saying but their subsequent actions spoke different, as that prior interaction became cyclical. Their entitlement was magnificent. All their life the white world had told them everything was theirs. That they laid claim to everything they touched. Who was this Black kid to tell them they couldn’t say a word? The task was immense and being the only African American in the locker room, I felt I was up against the world. I began to branch away. Each originator of Negritude speaks on the moment they truly begin to reject the world around them; for Césaire it was post high school in Martinique as he found himself incredibly displeased with the incessant adoration of all things European. For Senghor, he rebelled against the notion his Senegalese high school teachers pushed that “through their education they were building Christianity and civilization in his soul where there was nothing but paganism and barbarism before.” [7] This moment was mine. I began to question everything. I questioned all of my friendships, asking who did I really like, who really liked me, who was fetishizing my Blackness, who was touting my friendship as an internal justification that they weren’t racist themselves? It wasn’t the overt racism I was repelling against as I had always done so, but now scrutinizing the covert. I began to notice more and more these projections of who people expected me to be. White mothers visiting and being extraordinarily surprised that I was a well-mannered nice boy to their sons, my roommates. I began to critically examine why these white kids were consistently asking if I had drugs at parties, why I wasn’t dancing, why all the time they were so stunned I had a “good” vocabulary. I questioned even the Black students that lived across from me my sophomore year. They let several of their immediate white friends gratuitously use the n-word which definitely made me look at them differently. But who was I to judge? I was only very aware of what the overarching pressing whiteness at an institution such as this could do to you. I heard a story from one of their white girlfriends with whom I happened to be friends with at the time tell me when she was alone in his room one night, she overheard his white roommate in the hallway call him a nigger behind his back. He thought she was asleep on the bed when she was in fact wide awake. This had happened months ago, and she’d never told him and now I felt called to action. But wait, was I in the right to go blow up his entire reality? Should I go tell him about his roommate with whom he had several months still to live, racially abused him months ago? Should I tell him his white girlfriend knew about it the whole time and didn’t come forward? That strain may have been too much for one man to handle in the current environment we existed. I didn’t have a conclusive answer.

All these questions that I was asking myself at the time, reflecting constantly made me feel rather isolated in my Blackness. There were times when I would be hanging out with my white friends and just couldn’t take it anymore to the point where I had to excuse myself. Wearing a second face was exhausting. I found our values, these core principles, the things that concerned us and were relevant to each of our current lives at the time, were not at all similar. The African -American art that I had fallen in love with, I tried to share that love with those around me, to communicate what it was doing, but those cries fell on deaf ears.

I returned the miniature, wondering what in the world had made him open his heart to me. That was something I never did; it was dangerous. First it was dangerous if you felt like that about anything, because then you’d never get it or something or someone would take it away from you; then it was dangerous because no one would understand you and they’d laugh and think you were crazy. [8]

When I began to retreat, the people around started calling me moody, as that was their interpretation of what I was going through and that adjective carried a tinge of pain. How could I express to them what was going on, what I was feeling, in this echo chamber of whiteness where there was no space for it? I was regularly attending BSU meetings and was a very active member on the Diversity & Inclusion board, which were my salvation during Junior year because I was fed up. I was fed up with white people looking towards me when a perceived hood rap song came on to rap it with me as if their knowledge of the lyrics gave them some sort of racialized “hip” validation. They looked to me for this rhythm that I was supposed to somehow impart on them. The “presence of the negroes beside the white is in a way an insurance policy on humanness. When the whites feel they have become too mechanized, they turn to the men of color and ask them for a little human sustenance…” [9] I began to distance myself from it all. I was finally realizing what I wanted in life and acknowledged that this wasn’t it. I was handing out Black power t-shirts in the dining hall for Black History Month. I kicked a kid out of my townhouse party who was wearing a “Make America Great Again” hat. I organized a school wide trip to the African American Art Exhibit: Soul of a Nation at the Brooklyn Museum. A trip where I wanted to see who was willing to step outside of their comfort zone and into a fresh space. Perhaps one of discomfort but that’s vital to breaking down our preconceived misconceptions. I was trying to find my footing, and this was my response to the oppressive whiteness I felt that permeated throughout this campus. It wasn’t much, but for me it was something.

[Senior]

Finality

“The echo of “nigga” chanted by the entire white crowd around me failed to reverberate through my bones as it once had the first time I began to socialize on this campus.” [10] It was Senior year and I no longer cared about attempting to navigate the social dynamics around me, I had given up the Sisyphus-like task.

Graduation was the light at the end of the tunnel and all that mattered. Yet in spite of my mental detachment, I still was disgusted when I saw students standing on tables at parties reciting ironic nationalistic Trump chants over Snapchat. I watched one of my better white friends who I think has been relatively aware of how I’ve struggled over the past couple of years make a racist remark about my skin color for the amusement of females. We were driving in his car late one night and as he was on facetime, a girl from the background called out “Where’s Diallo?” He replied, “you can’t see him, he's too dark.” It’s funny because you think that three long years at a PWI in New England means you’ve heard it all, that you’ve mastered a way to encounter the racism you hear on a daily basis, and yet racism doesn’t care about your feelings. It rips and tears and eviscerates as it always finds a way to leave you stunned. In a very perverted sense, the PWU shaped me to judge my white friends and teammates on who had said the least prejudiced things. I would look around at a party, at this homogenous mass of students chanting the n-word with a cultish fetishized desire and feel a helplessness from not having the strength to stop it all. I knew it wasn’t my job and that I couldn’t cure all ignorance. If I spoke, would they even listen? Still encroaching upon my mind were thoughts of “Was I giving up, was I too scared, was I in fact helpless, was it even worth it?” I started leaving the room when “Dreams and Nightmares,” a song by Meek Mill came on with the repetitive use of the n-word as I knew I would lose friends by the end of it. I said I didn’t care but to a degree I couldn’t help it. This beast of burden, this system I had been involved in for four long years had snared me in its entrapment and the only true liberation I felt possible was graduation. Graduation. Graduation. Where I would no longer have to periodically switch off parts of my consciousness to survive. Leaving all this in my past was the light at the end of the tunnel, but even so a little voice deep down kept whispering to myself something I didn’t want to admit. That it wouldn’t end here. I quieted those whispers and repressed that voice because I needed hope to surmount this last collegiate hurdle of Senior year. My diploma meant more than just a degree but a finality I was ready to claim on a sun that had finally set.

As I write this last paragraph, it is a very surreal moment which now claims my conclusion at this institution. To analyze who I’ve been and who I’ve now become, so my journey ahead is better illuminated. Now it is my time to carve out my own individualized path free of my PWU’s constraints. I was a man of two faces and am now no longer. So, in a paper hopefully devoid of clichés, I’m going to end it with a rather applicable one. Know from whence you came, so you can know where you are going.

Endnotes

[1] Diagne, Souleymane Bachir "Négritude", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2018 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.),

https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2018/entries/negritude/.

[2] Frantz, Fanon. “Fact of Blackness.” In Black Skin, White Masks, 109-140. Grove Press, 1952, 110.

[3] Fanon, Fact, 114.

[4] Diagne, Negritude, 5.

[5] Fanon, Fact, 112.

[6] Fanon, Fact, 128.

[7] Diagne, Negritude, 11.

[8] Ellison, Ralph. Invisible Man. Modern Library ed. New York: Modern Library, 1994, 43.

[9] Fanon, Fact, 129.

[10] Pérez, Loida Maritza. Geographies of Home : a Novel . New York: Viking,1999. [Adaptation]