Inking Social Skin: Tattoos as Care of the Self and Embodiment of Identity

Introduction

Tattoos may be understood as a way to navigate one's own social being and the continuity of it over different social contexts and parts of the self. [1] They can be traced back to ancient times and have several thousand years of history across the world in different cultures, with different meanings and rituals. [2] Our insight comes from a later “western” view on tattoos where for a long time, tattoos were understood and stigmatized as a social deviance, reflecting a flawed moral identity for tattooees. [3] Although this understanding of tattoos is less prominent in today's “western” society, we want to counter this history of prejudice with an understanding of tattoos as a means for embodying identity and as a care of the self.

In this visual project, we were inspired by the term social skin, originally used by anthropologist Terence Turner, who in 1980 wrote an article titled The Social Skin. [4] This article grew from his ethnographic field work with the Kayapo people in Brazil, and specifically the way they adorned their bodies according to the rules of their society, focusing on things such as hair, piercings, and jewelry. He defined social skin as way for bodies to interact within social contexts, and in his view, bodies were the boundary between the individual and society but they were also an arena for interactions between the two. [5]

These interactions can be expressed through bodily adornments, which can be seen as socially connotated alterations of the body. [6] Bodily adornment becomes an embodiment of social life and belonging, and therefore acts as a gateway into understanding the social context itself. [7] In this sense, methods of bodily adornment function not only as a branch of social structure, but also as a means of identification for the persons in it. [8] These social structures and identity, embodied and intertwined, make up the social skin of our participants; their bodily adornments are their tattoos.

The project Inking Social Skin presents two intertwined aspects, where the first one touches on how identity is embodied in having tattoos and the second aspect touches on identity embodied from getting tattooed. Identity embodied in having tattoos dives into what tattoos say to both their carrier and to their surroundings. In other words, tattoos perform as and constitute physical manifestations of personal experience for our participants. This supports them in, as they put it, feeling beautiful, confident, cool, or as themselves. The second aspect, identity embodied from getting tattooed, dives into the ritual, dialogue, and creative process that takes place between the tattoo artist and their customer during a tattoo session. Touch, music, conversation, and the room all charge the tattoo with meaning, story, and value, and ascribe these to the person getting tattooed as well.

On Embodiment

Tattooing is inherently an embodied practice, since it is work on and through the body. The aspects above - having tattoos and getting tattoos - are processes of embodiment of identity because, as our participant Liv states, ”[the tattoos] become part of [one’s] body. They become part of who you are.” In this, “who you are” becomes synonymous with the body. This relation is further justified when we later compare work on the body with Foucault’s work on the self. The identity processes our participants speak of are therefore inherently embodied processes, work on the self and body intertwined. Tattoos as a process of embodiment functions as a way to manifest identity through the body by acting on its physical site, forming a self that is fluid.

Moreover, this project recognizes the process of embodiment as a method to reclaim the body after trauma. Some of our participants explain how tattoos help enhance a sense of “this is my body” after traumatic experiences such as depression, body dysmorphia, or imposed harm. The context of tattooing then works as a somatic practice or ritual that lets them bridge the experienced split between body and mind, and develop a more loving and caring relationship to themselves. We will not explicitly develop on the topic of trauma, but deem the experience of struggle and healing relevant to how our participants experience identity as embodied. Recognizing tattoos as a process of embodied healing further justifies the central term of this project: care.

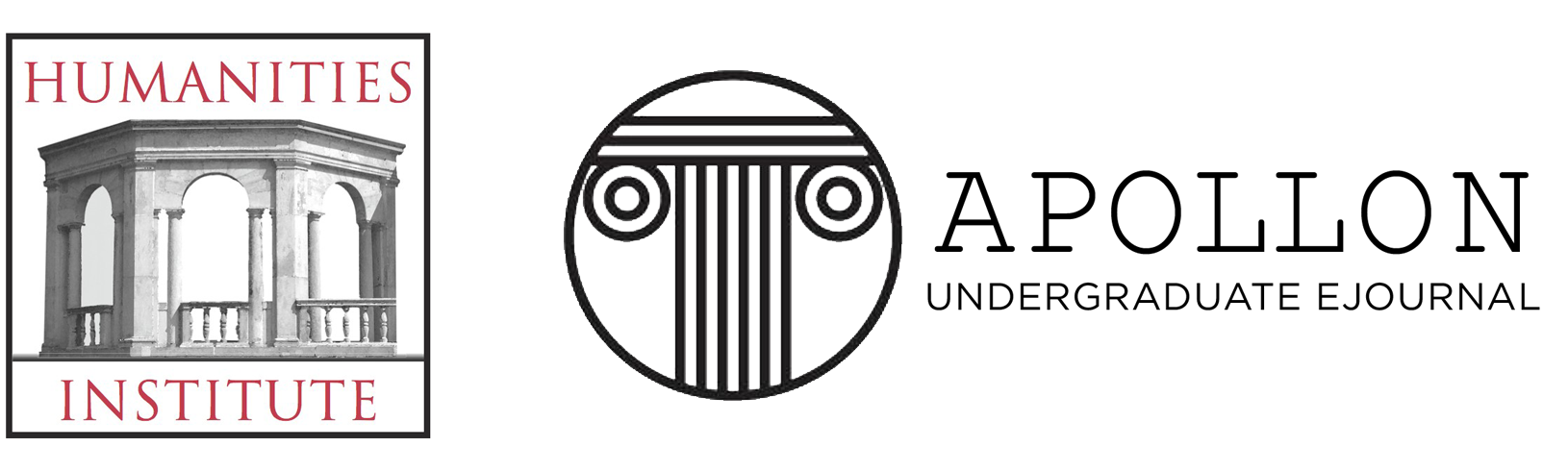

Figure 1: Linus’ tattooed arm by Klara Pertmann, 15/4/25

Theoretical Framework

We argue that tattoos as a process of embodiment is a practice of care of the self. The ethnographic material presented in our film is hence grounded in the French philosopher Michel Foucault’s theory of care of the self. Broadly, Foucault’s most influential works concern concepts such as power, knowledge, ethics, freedom, and sexuality. These concepts are not seen as separated from each other but connected through various relations and games. Through this intertwined view of societal structure, he was able to critically understand authority and social control. As part of his theoretical work, care of the self was first introduced in Foucault’s History of Sexuality, vol. 2 [9] and 3 [10] and describes how ancient philosophers understood the importance of caring for body and mind. This care was a way to live a fulfilling life in which one cares for oneself and others. Foucault further expands on the practice of care of the self in Ethics: Subjectivity and Truth [11] by connecting it to concepts of ethics, games of truth and power relations. We include these concepts in the idea of tattoos as practices of care of the self.

In our discussion, we use the translation “care for the self” in an almost synonymous manner. Our intention is not to allude to self-care in the modern and individualistic sense, but to ascribe a political and healing dimension to care that inevitably arises once embodiment is considered. This understanding of care for the self is also influenced by Black lesbian feminist Audre Lorde's view on self care. Lorde’s contributions to intersectional feminism and activism are substantial. Her engagement in essays, poetry and activism alike illustrates the importance of practice in the work one does, such as self care as a practice of self preservation for individuals in marginalised communities. Inspired by Lorde’s view of care, we adopt Foucault’s care of the self to understand the experiences of our participants, and present a perspective on how tattoos help form fluid, subjective, and embodied selves that are also creative, collective, and political in a social sense.

Figure 2: Tattooing station at studio Myriad, by Liv Mehlin Södervall, 04/22/25

Methods

The methods used for this project were fieldwork in the form of sit-ins during sessions at the two tattoo studios, Myriad and Glöd, as well as semi-structured interviews with both tattoo artists and tattooed persons. While observing and interviewing, we used cameras to gather the visual material that make up the central pillar of this project.

The field site where we conducted our work was one of psychological and bodily vulnerability, since it involved being in the space of, as the tattoo artists state, “making physical wounds.” Similar to a needle, eyes and/or a camera is an intervention into the participant's personal sphere, even more so when they are simultaneously giving away facts about their personal life. But as tattoo artist Natalia explains, the vulnerability of the situation might also be the very reason why people open up. Another tattoo artist, Milla, emphasizes that her clients are human beings, not canvases, and that the tattooing process is one of collaboration. We wanted to follow the ethos of our local context [12] and hence, we valued doing research with our participants, not doing research “to” them. [13]

Following this, film felt the most appropriate medium to represent the tattooed bodies and their stories. It allowed access to multiple angles in terms of opinions but also spatially, since living bodies move and behave differently from second to second. Film was also useful because rather than have us speak for the participants and have their words and experiences be translated through us, they could speak for themselves. Some participants consented to their faces and/or names being shown while others did not. Some appear only in still images and voiceovers, others in film, but all were represented in the way they preferred to participate. We then showed the edited version of the film to our participants and invited them to comment on it in order to make sure that they felt accurately represented. [14]

In other words, this project is thanks to, and highly dependent on, our participants. We aim to represent their experiences of having tattoos and getting tattooed, shared through interviews and the intimate moments of a tattooing session. These are personal and subjective experiences, and rather than an idea applicable to all experiences of tattoos or tattooing, we aim to showcase this particular and special potential of tattoos that we believe is interesting and inspiring.

Cultivation of the Self

Our participants describe having or getting new tattoos as a manifestation, creation, or change of body and soul. Adam got a tattoo on his throat as a reminder that his opinions are of value. Liv got a cartoon portrait of her “French alter ego” to become the “cool” person she wanted to be at a time when she felt fragile and lonely. A semi-colon symbolizing mental illness reminds Madde that “[she] made it through, and [she] is here now.” The tattoos embody aspects of the participants’ identities, such as who they are, what they have lived, or what they want to do or be. The tattoos hence act as active processes of embodying self-identity, letting their owner be a self with a past, a present, and future aspirations.

Foucault writes that in order to be a self, it is crucial to care for oneself. [15] Similarly, tattoos are crucial to the identity-process our participants speak of and could, when inspired by Foucault, be considered as care for oneself, as care of the self, in order to be a self. Care and self are explicitly connected in the theory of care of the self, which here is employed to recognise self-identity as a practice. More specifically, this self-identity is the embodied practice of tattooing and having tattoos, such as how Madde reminded herself of her past with a semicolon to know who and where she is now. Moreover, Foucault describes care of the self as a practice that encapsulates self-cultivation[16], self-reflection[17], and self-awareness.[18] Tattooing and having tattoos are such practices that involve cultivation, reflection, and awareness of the self, as the wearer first considers what and where to tattoo, and then continues to live life in relation to the tattoo. The tattoos are a means to learn of one’s subjectivity and explore new parts of it, to acquire new modes of understanding and being, and create self-identity.

Figure 3: Liv with the tattoo of her French alter ego on the right side, by Kara Pertmann, 15/4/25

Self-identity is connected to norms and ideals in one’s social surroundings. [19] For a tattooed individual, this interconnectedness might take the form of a “tattooed status. [20] Today, this status is not so much about total deviance from the status quo, but rather about opening up a space within a hegemony of social norms where those norms can be questioned. [21] In this, tattoos can at once function as both affirmations of the self and critiques of society. [22] Alterations of the body may be a way to reclaim the body from harmful ideals and create control over the way one is perceived. [23] Several of our participants describe how they use tattoos to issue agency in systems that exclude, sexualise, or criticise their bodies.

These same tattoos are also mentioned as ways to communicate subjectivity to social surrounding by using symbolism that goes beyond the limits of spoken language and showcasing identity in an embodied way. [24] The participant Andréa’s tattoo of Sappho relates to external perception, as an homage to her queerness, but also to remind herself that her body is her own and that society’s ideals should not interfere with the agency she has over it. We propose that the coexistence of resistance and personal identification on tattooed bodies speaks to how persons negotiate themselves within Foucauldian social systems. Just like Adam’s throat tattoo, Liv’s French alter ego or Madde’s semicolon, Sappho on Andréa’s stomach is a way to care for the self, as a multifaceted method of ethical work on the self.

Figure 4: Andréa with Sappho, by Liv Mehlin Södervall, 04/24/25

Ethical self-formation: games of truth, relations of power, and freedom

The work on the self, described above through Andréa’s tattoo of Sappho, is ultimately a self-formation that can lead to freedom. We can expand on this with the related Foucauldian concepts of games of truth and power relations. But first, we must understand why Foucault considers the self, the work on it, and the formation of it to be ethical. He writes that ethics are not static or abstract, but an embodied form of being and behaving. [25] Adhering to these ethics in both a subjective and social way is the foreground to an ethical self. Furthermore, ethics is the conscious practice [26] and reflective [27] part of freedom. [28] Ethics and freedom are intertwined throughout the self-formation of caring for the self, and reflection is the key.

Reflecting on the self and social norms is foundational in the care of the self. Through reflection, one acquires knowledge of the self as well as the conducts and principles of a society. [29] This is a way to “equip oneself with [...] truths.” [30] This practice is part of self-formation and furthermore, related to games of truth, which are the premises for how truths are constructed. [31] These premises include the systems of knowledge that exist in a specific time and place, and while the rules by which the truth is produced are not something individuals come up with themselves, subjects constitute themselves through and have to actively relate to these games of truth. [32] As a matter of fact, our participants do relate to a sense of truth; they describe being true to oneself, or “to feel like myself” as reasons for tattooing the body. However, they do not allude to an essentialist authenticity or belief that the self is necessarily more static or true than anything else. Rather, their relation to the self is best understood through Foucault’s definition: the self is not a substance, but a form. [33] The participant Navi describes the self as a tool and instrument that changes form depending on “what has to be done.” The tattoo is a creature that makes the movement of the self visible. Tattoos could hence be seen to have the social backdrop of games of truth in which the form of the self, in itself a construction of truth, can be used as a tool.

Foucault also links the construction of truth to power and power relations, since the person who can formulate truth also has power. [34] In this web of truth and power, Foucault encourages one to acquire “the ethos, the practice of the self, that will allow us to play these games of power with as little domination as possible.” [35] This ties to Foucault's positive view of power as essential in human relationships - society cannot exist without it. [37] Power relations exist everywhere and are always at play; they are different from the static state of domination and not inherently bad, since everyone inevitably negotiates them through different practices. These practices are often of the body and form an ethical self that is able to critically recognise and converge power relations. One constitutes truths of the self and gains agency in power relations through the process of forming an ethical self, which is to claim freedom. [38] This is what happens when Navi’s self changes form depending on “what has to be done”. To become or be tattooed is to recognise and play with truth and power. Like Liv says, “one of the coolest things about tattoos is that you have the power to decide something about yourself, and do that.” Similarly, Madde emphasises how being tattooed is a manifestation of “going [her] own way.”

However, in order for positive power relations to exist, all parties must have the ability to negotiate the form of the power relations. [39] In light of this, for a tattooing context to be a process of care of the self, a certain degree of agency for all participating actors is necessary. If one is stripped of agency in a state of domination and therefore not able to take part in one’s own construction of the self, there is risk for harm. [40] Our tattoo artist participants did communicate that if fieldwork were to be conducted in tattoo studios that do not practice the same ethos of care and healing as they do, the outcome of the project could have been different. We take from this that we have a specific sample of participants. If we were to conduct fieldwork in spaces that have a different approach to freedom and agency, the analysis of tattooing as care of the self may not apply. The social context determines the potential of care, because care is a social practice.

Figure 5: Milla and her customer at Myriad, by Liv Mehlin Södervall, 04/22/25

Care as Social Practice

Community and collectiveness are pillars when viewing care as a social practice, and equally important as Foucault writes of care of the self. Power, truth, and self-cultivation are all social phenomena that do not exist in isolation. [41] The practices utilized to constitute oneself do not come from the subject, but from the culture and society they live in, whether these be suggested or imposed. [42] The constituted self is a subject in relation to social and political practices, and Foucault writes that the goal of forming an ethic, away of being and behaving, is to make this relation possible. [43] This point is crucial: self-cultivation is not a solitary practice, but a social one. [44] Care of the self requires receiving help and guidance from others; the goal is not to be independent from others, but from that which is not necessary or significant, such as the opinion of others, habit, or vanity. [45] When caring for the self it is also necessary to acknowledge and fulfill one's social responsibilities to the collective; one cannot care for the self in an ethical way without also caring for others. [46]

In line with this, and as we have previously stated, we do not refer to caring for the self in the modern individualistic sense, but as a practice grounded in community. In contrast, the self as a possibly individualistic project might be cultivated in the process of tattoos, especially since tattoos have been incorporated into more normative and commodified aesthetics. In light of this, tattoos as care of the self could be misunderstood as a type of self-care that centers the individual and attaches little importance to community. While this may be true in some cases, our perspective does not apply to every tattoo on every body. Rather, our participants mainly reflect on and cultivate themselves with awareness of how their identities depend on human relations, while also taking pride in the political implications of diverging from the hegemonic look.

This might be further understood through Audre Lorde’s works, in which she considers caring for oneself to be self-preservation, and in this sense, a radical political act. [47] In the epilogue of A Burst of Light, she writes of the connection between personal struggle and political activism. Rejecting the notion of omnipotence as defence, she instead recognises how both the personal and political can be battled with the power of assessing and appreciating “what [she] can and do accomplish, using who [she] is and who [she] most wishes [herself] to be”. [48] With these words, that ring similar to how participants Madde and Liv expressed what their tattoos mean, Lorde promotes self-reflection and awareness as a base for power to be used in the battle of political activism. Caring for the self is self-preservation, but also community preservation. Tattoos could be regarded as a practice of this, especially because of their roots in marginalised communities. [49] Hence, the care of the self is, in the example of tattoos, also a practice of care for the self and others.

Figure 6: Cat and tattoo artist Natalia in a session at Myriad, by Liv Mehlin Södervall, 07/17/25

Tattoos as Care of the Self and Others

The social aspect of care illustrated above ascribes value to relationships and meetings. In relationships inhabited by care for the self and others, said relationships are impacted by these practices, “giving them a new coloration and a greater warmth [...] an intensification.” [50] Foucault quotes Seneca: “you are my handiwork” [51] to exemplify a relation present in relationships of care. This is a clear parallel to putting the art of tattoos on someone else's body. The participant Linus says that by letting someone put their art on his body, “there’s a development of some kind of relationship” between him and the tattoo artist. It is a relationship built on trust - “a different kind of trust than you get with many other people.” The tattoo artist Natalia describes the intimate position tattooing implies: she is “close to someone’s skin” and is changing it through a procedure. The trust Linus is referring to might grow from the intimate nature of tattooing that Natalia describes, creating a bond through the act of care. Navi states that tattoo artists can be reckless with their clients when tattooing, but that during the session with Natalia, Navi ultimately does not feel threatened, but a sense of trust.

When informed by care, the relationships present in the practice of tattooing might develop the coloration, warmth and intensification that Foucault writes of. Participation in the collaborative and creative process of tattooing offers a way for personal knowledge and senses to be properly embodied. The tattoos become “charged” with the energy, touch, music, and conversation from the session. Tattoos are not only embodied identity because of the inspiration behind it or the social skin it creates; the session itself further strengthens how the person identifies with their tattoo also after the session, in their own lived life. This brings us back to how both tattooing and having tattoos are intertwined in the lives of our participants, and therefore also in our film.

Figure 7: Milla and her customer at Myriad, by Liv Mehlin Södervall, 04/22/25

Conclusion

This project explores how having and getting tattoos involve a subject working and reflecting on, caring of and for, their body, self, and others. Having and getting tattoos are then practices of care of the self. Tattoos, as embodiments of identity, are to be also understood as embodiments of culture. They are bodily adornments deriving from the culture they exist in and simultaneously practices for individuals to navigate that culture, creating social skin. They become a tool for negotiating and converging Foucauldian relations of power and games of truth, forming an ethical self that has agency and freedom. Since care of the self also extends to caring for - for both oneself and others - the self formed is collective, creative, and political. Through the art of tattoos, one can participate in culture in a way that creates space for everyone and everything to exist in different forms. Navi exemplifies this, saying tattoos are a reminder “that it is possible to create things, if I choose to.” Their tattoo artist, Natalia, describes this as her goal: she wants people to leave the studio feeling that their idea of the world has expanded.

Endnotes

2. Mary Kosut, “Tattoo Narratives: The Intersection of the Body, Self-Identity and Society,” Visual Sociology 15, no.1 (2000): 79, https://doi.org/10.1080/14725860008583817

3. Nichols and Foster, “Embodied Identities,”

4. Terrence Turner, “The social skin,” HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 2, No. 2 (2012), https://doi.org/10.14318/hau2.2.026

5. Turner, “The social skin,” 486.

6. Turner, “The social skin,” 486.

7. Turner, “The social skin,” 501.

8. Turner, “The social skin,” 487.

9. Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality Volume 2: The Use of Pleasure, trans. Robert Hurley (Vintage Books 1990).

10. Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality Volume 3: The Care of the Self, trans. Robert Hurley (Pantheon Books, 1986).

11. Michel Foucault, Ethics: Subjectivity and Truth, ed. Paul Rabinow, trans. Robert Hurley et al. (New York: Autonomedia, 1989).

12. Sarah Pink, Doing Visual Ethnography, (SAGE Publications, 2013), 63.

13. Pink, Doing Visual Ethnography, 63.

14. Pink, Doing Visual Ethnography, 119.

15. Justen Infinito, “Ethical Self-Formation: A Look at the Later Foucault”, Educational Theory 53, no.2 (2005): 156.

16. Foucault, The Care of the Self, 43.

17. Foucault, Ethics 284.

18. Foucault, Ethics, 285.

19. Jessica Strübel, & Domenique Jones. “Painted Bodies: Representing the Self and Reclaiming the Body through Tattoos,” The Journal of Popular Culture 50, no. 6 (2017): 13, https://doi.org/10.1111/jpcu.12626.

20. Nichols and Foster, “Embodied Identities,” 1.

21. Nichols and Foster, “Embodied Identities,” 5.

22. Nichols and Foster, “Embodied Identities,” 5.

23. Strübel and Jones, “Painted Bodies,” 7.

24. Nichols and Foster, “Embodied Identities,” 3.

25. Foucault, Ethics, xxvi.

26. Foucault, Ethics, 285.

27. Foucault, Ethics, 286.

28. Foucault, Ethics, 284.

29. Foucault, Ethics, 285.

30. Foucault, Ethics, 285.

31. Foucault, Ethics, 282.

32. Foucault, Ethics, 297.

33. Foucault, Ethics, 290.

34. Foucault, Ethics, 298.

35. Foucault, Ethics, 298.

36. Foucault, Ethics, 298-299.

37. Foucault, Ethics, 283.

38. Foucault, Ethics, 291.

39. Foucault, Ethics, 292.

40. Infinito, “Ethical Self-Formation,” 157-158.

41. Stephanie M. Batters, “Care of the Self and the Will to Freedom: Michel Foucault, Critique and Ethics”. Senior Honors Projects, Paper 231 (2011): 7, https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/srhonorsprog/231.

42. Foucault, Ethics, 291.

43. Foucault, Ethics, 300.

44. Foucault, The Care of the Self, 51.

45. Foucault, The Care of the Self, 59.

46. Foucault, Ethics, 287.

47. Audre Lorde, A Burst of Light: Essays (Ixia Press, 1988).

48. Lorde, A Burst of Light, 133.

49. Nichols and Foster, “Embodied Identities”, 4.

50. Foucault, The Care of the Self, 53.

51. Foucault, The Care of the Self, 53.

The authors of Inking Social Skin, Klara Pertmann, Liv Mehlin Södervall, Finn Spies Sjögren and Louise Persson, are four bachelor students at Lund University, majoring in Social Anthropology. Their interests cover questions related to queerness, gender, the body, nature, and their various intersections.

Liv Mehlin Södervall

Liv Mehlin Södervall is intrigued by the intersections of Gender Studies and Social Anthropology, pursuing an education in the two disciplines. Through fields of alternative subcultures as well as feminist and queer communities, she is especially interested in processes of subjective and social identities. She believes in the emancipatory potential of feminist ethnographic work.

Klara Pertmann

Klara Pertmann is curious about how the body, being a physical site for collective and personal memory, is experienced and performed in social encounters. Being a dancer, she approaches movement as material, and enjoys using creative practices and participant observation to study how this is present in identity, community, and art.

Louise Persson

Louise Persson is interested in the fusion of culture and nature and how both in a balanced way should and can thrive. In addition to a bachelor's degree in Social Anthropology, she would like to pursue a bachelor's in Human Ecology. In both disciplines she thinks a mindset of openness to understanding several perspectives is crucial, and with that multiangle view, bringing stories to life.

Finn Spies Sjögren

Finn Spies Sjögren is interested in the creation of identity and community, and especially queer identity and community, as well as East Asian cultures and languages. Solidarity, community and mutual respect are important cornerstones that inform their approach to research in all areas.