A Distinction Between Sense of Personal Identity and the Produced Self

By Cameron Bunker

The self can be defined as an individual’s experience that one is a separate entity from other beings. This paper will discuss this notion of self, how it is produced linguistically, and its relation to the sense of personal identity. Several theories of the self will be analyzed so this relationship between self and personal identity can be properly defined. In their book, The Discursive Mind (1994), psychologist and philosopher Rom Harré and neuroscientist Grant Gillett argue for a theory of self. Their theory claims that through the use of language we create the self. Harré and Gillett introduce the concept of sense of personal identity; the sense of an identity that one can have of their self and of other beings. By binding this sense of personal identity through pronoun usage (e.g., I), we create an agent that we believe to be responsible for our location, our thoughts, and other mental activity through our discourse. This is the discursive production of self; one can bind the components of personal identity, and express it through discourse. My goal is to bring out the distinction between sense of personal identity and the discursively produced self. Harré and Gillett’s theory does hold limitations, a proper definition of the binding in sense of personal identity and its implications on self-production need to be recognized. This paper will feature a proper definition of the process of binding in order for Harré and Gillett’s theory to be better utilized in my goal. I will also be discussing the implications of how this process of binding is used in self-production.

In her article, The Presence of Self in the Person: Reflexive Positioning and Personal Constructs Psychology (1997), psychologist Raya A. Jones analyses psychologist George Kelly’s Personal Construct Theory and Harrés positioning theory to posit a theory of self. Kelly’s theory posits that the self is a construct that is innate within humans while Harré’s theory sympathizes with Harré and Gillet’s theory in that the self exists only in discourse.

In addition, sense of personal identity without self-production needs to be examined. I will address this by discussing findings by biopsychologist Gordon Gallup. In his article, Self-Awareness in Primates: The Sense of Identity Distinguishes Man From Most But Perhaps Not All Other Forms of Life (1979), Gallup discusses findings that chimpanzees have self-awareness. I will be discussing these findings in light of Harre and Gillet’s model of sense of personal identity. This paper will analyze all of the previously listed works in order for the relationship between sense of personal identity and the self to be properly defined.

The Discursive Mind (1994) features a series of chapters on discursive psychology, the study of psychological phenomenon through discourse. Harré and Gillett posit the discursive method; the method focuses on how our mental states are not just reflected in our communication (96). Our mental states are understood through internally and externally perceived discourse. Discursive activities display what we think. In addition, all our thoughts can be communicated through discourse. When we think, our mind holds private thoughts, that is to say private discourse, which we can then keep to ourselves (Harré and Gillett 48-49). However, when we communicate these thoughts, they become public discourse. Those thoughts are now open to potential perceivers. Thus, by studying interactions between people, an effective examination of the human mind can understand the mental states exposed by conversational context.

Harré and Gillett apply this discursive method to articulate their theory of the self. Language plays two key roles in discursive psychology (99). The first is to exhibit the discursive activities of people; discursive activities contain the mental properties of our cognition (e.g., a person that asserts p gives the observer knowledge that they believe or think p). The second being that language acts as a model for the analysis of non-linguistic expressions (e.g. facial expressions). It is vital, in the discursive method, that non-linguistic expressions be analyzed as if they were a part of language. These non-linguistic expressions can still express the mental properties of our cognition (e.g., When a person believes or thinks p we can observe their facial expression and predict, with limited accuracy, their belief or thought).

Harré and Gillett make the assertion that people live in two worlds: the discursive and the material (99-100). The discursive world is full of symbols and signs and is constrained by norms (e.g., social norms such as respect of others). The material world is the physical world. To elaborate, the material world is full of physical objects and is constrained by certain laws (e.g., gravity). Human beings can effectively thrive in both worlds using skills they acquire. Harré and Gillet posit two types of skills: material and discursive. Material skills are those that we use to alter our physical environment (e.g., physical strength). Discursive skills are those that we use to communicate effectively and manipulate symbols (e.g., language skills). It is important to note that these two worlds do not constitute a substance dualist theory. It is a dualism of what it is objective (the material world) and how we subjectively perceive it (the discursive world that differs from culture to culture). Harré and Gillet make the assertion that they cannot simply reduce the two worlds to one another, but they do not recognize the mind or the discursive world as a mental substance (99-110).

If the mind is not considered a mental substance, or if there is no mental substance at all, then how can the self exist? Harré and Gillet use arguments from language usage to provide evidence that the self is part of the discursive world; the world that does not belong to substance but its relation to substance is part of the relation of the discursive world to the material world (100-101). To clarify, the discursive world is a projection of the material world. The discursive world exists only through symbols. This is in contrast to the material world in that the material world exists physically. The self is not part of the material world but is produced from the binding of sense of personal identity. Some components that make up the sense of personal identity remain based on the objective world (e.g., sense of bodily location and time). The self is part of the discursive world in that it is created through our use of language. We can examine this concept of self from a variety of different languages.

The English concept of self is difficult to translate into other languages from different cultures (Harré & Gillett 101). The Spanish phrase “Mi mismo” means the personhood of myself. It does not translate to soul or mind. The French phrase, “Moi-même,” does not translate to the meaning of self. Moi-même translates to ego and the phrase is taken from Latin. It is not reflective of the Cartesian dualism that posits that the mind or self is a substance. Harré and Gillett do, however, assert that a sense of personal identity is universal and can be found in most, if not all, human cultures. These differences in cultural language use demonstrate that while a sense of personal identity is universal, the discursive production of selves will vary. We all carry the components that make up personal identity, and therefore we can make a sense of it. However, we differ in our binding of these components that allow us to have a sense of personal identity. This difference in binding of the sense of personal identity is reflected in different discursive productions of the self.

Personal identity is a topic that has been debated a great amount. By taking the discursive viewpoint, Harré and Gillett assert that we can explain personal identity and find out the ties between personal identity and the self (103). When trying to learn about someone else one might ask questions about their name, job, favorite food, hobbies, etc. What they are trying to do, Harré and Gillett maintain, is figure out the components within the target person’s sense of identity. Figuring out someone else’s sense of identity is an empirical task. It is a task based on discourse. To learn about the sense of identity of someone else, engagement in communication of some sort is required. What about figuring out one’s own identity? Normally, we do not question whether or not we are the same person we were ten minutes ago or even five years ago. That would be absurd. We have a sense of identity that we can bind into a self through our memories. This sense can include any amount of the moral and social identity components that are remembered and identified with.

Harré and Gillet focus on how the production of self is tied with this idea of binding of sense of personal identity (103-104). They posit a hypothesis of what constitutes the sense of personal identity. There are four ways we subjectively perceive our identity. First, we have a sense of location of where we are or, in other words, a point of view. Second, we have a sense of time to which we exist moment by moment. Third, we have a sense of obligations that hold us to our relations through external forces. Lastly, we have a sense of social world in which there are statuses and reputations. Harré and Gillet take the stance that we experience ourselves as a location, not an entity, in which we perceive and act upon external beings. We are also perceived and acted upon. In order to examine the production of self through discourse we need not to examine the subjective experience of personal identity, but only the discourse that is a reflection of it. In other words, the aim of the discursive method is to observe a person’s projection of self based on their subjective sense of personal identity rather than the subjective experience itself. This projection of self can be examined through pronouns.

Consider the indexical use of the pronoun I in the English language. We use this pronoun to bind our sense of personal identity (Harré and Gillett 106-108). When used in a sentence (e.g., I see a window) we refer to our body in a location and as a subject or agent of an action. We create or construct the self in our use of the word I. It binds the complete sense of personal identity to the actions and perceptions going on with the identity. Using I indexes all the four doctrines that constitute personal identity: sense of location, time, agency, and social relation. Even if the statement does not reflect a social or moral role (e.g., I see a window), I still indexes the binding of sense of personal identity. The person still includes their sense of moral and social roles in that “I.” This stream of consciousness that constitutes personal identity cannot be perceived externally due to its privacy. Harré and Gillett present British philosopher David Hume’s view: “We cannot explain the sense of personal individuality we have of ourselves, by looking into ourselves for some entity that is our self and of which all our thoughts, feelings, and so on are attributes” (Harré & Gillett 103). In order to witness an individual’s components of personal identity, we must examine it through their discursive production of the self.

However, different cultures vary in their use of pronouns (Harré & Gillett 104-105). This helps further illustrate the difference in discursive self-production from the sense of personal identity. Consider the Japanese culture. In the Japanese language there are more pronouns in discourse than there are in the English language. There are so many pronouns that the Japanese sometimes will not use pronouns in their discourse. This leads to issues regarding production of the self and the binding of sense of personal identity. Cultures who do not use pronouns in discourse will endorse holistic communication. A discursively holistic culture promotes emphasis on diminishing the importance of sense of personal identity in its cohorts. With a diminished sense of personal identity there will be less production of selves in discourse and less emphasis on the importance of individual sense of personal identity binding. By examining the Japanese's pronoun usage, we can see further evidence for Harré and Gillett’s theory. Cultures have different pronoun usage which entails different senses of personal identities, and therefore there is no universal self that exists in substance. The self is produced from realization of the ability to bind the components of sense of personal identity. This sense of personal identity is universal but differs in the level of strength that it is subjectively perceived and bound.

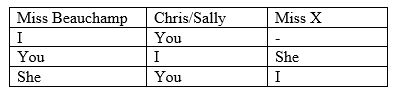

To further give evidence for their theory, Harré and Gillett examine a case study of Multiple Personality Disorder (now called Dissociative Identity Disorder) and the pronoun usage of the patient (109-110). Dissociative Identity Disorder is a disorder in which a person (body) seems to have multiple senses of personal identity. Dr. Morton Prince, an American physician, conducted an early study on this phenomenon (1905). He found that his patient, Miss Beauchamp had this condition and observed a series of the different personalities that arose from Miss Beauchamp. In The Discursive Mind (1994), Harré and Gillet set out a table that is referenced from Dr. Prince’s report (109):

The table above lists the pronoun usage of the three different personalities that Prince reported. The first personality, Miss Beauchamp, was Prince’s patient. Her use of pronouns was correct within the rules of the English language. Miss Beauchamp was never aware of the other personalities but would still experience the consequences of their behavior (e.g., sometimes Sally would get severely intoxicated and Miss Beauchamp would experience the hangover). However, the other two personalities revealed an unintelligible speech involving a confusing use of the English pronoun system. The second personality, Miss X, never gave herself a name and was never in the speech of Sally, the third personality. Sally was aware of Miss Beauchamp and referred to her using “you” or “her” (when she referred Miss B. to someone else) even though they inhabited the same body. Prince thought that by getting the other personalities to use the correct pronoun structure he could fuse the perceived selves. Harré and Gillet interpret Prince as trying to get the other personalities, Sally and Miss X, to use I whenever they referred to themselves and the other personalities. He tried to get the alternate personalities to only use “you” when talking to a person other than the body in which they inhabited. In doing this, he thought he could fuse the perceived selves, and thus only one would remain.

Harré and Gillett posit that it is not three agents inside Miss Beauchamp competing for control (109-110). It is three selves presented in her discourse. By examining the chart we can see that the indexical pronoun usage of I was consistent in the representation of the location of the speaker. However, the use of I by the personalities does not infer the same moral agent. For example, Miss. B would say “I walked into the woods” (referring to a task performed by sally), but she would not say “I drank a sinful amount of alcohol to achieve a hangover” (referring to when Sally drank to give Miss. B a hangover). Each personality bound its sense of identity differently. The phenomenon lies in that there were three selves being produced by one body through the discourse.

The theory of self-presented in the Discursive Mind succeeds in several ways. It avoids having to discover or elaborate on what a substance self would be (i.e., the metaphysical properties that would constitute a self in substance). Giving evidence that the self has physical properties is a daunting task. Would it consist in the brain chemistry, as a mental substance, or a soul? I would not know.

Harré and Gillett argue that the self is created in discourse, therefore it is readily accessible to examination. By adopting the discursive viewpoint, the self in discourse can be witnessed and experienced empirically. We can see how others present their self in their discourse. People construct their self through binding their sense of personal identity. The theory need not be more self explanatory; one can simply use pronouns to construct their self based upon their sense of personal identity and observe identities in others. Their actions, thoughts, and other sorts of mental activity can be witnessed in the discourse.

The theory explains how people are able to use pronoun usage and sense of personal identity to construct their self in discourse. People have a sense of their location, a sense of time in which they are existing, a sense of moral responsibility that is set by their culture, and a sense of a social world that they live in. With these doctrines, people realize a sense of personal identity with their perceptions and actions.

Harré and Gillett’s theory of self explains the differences of self-production from a cultural standpoint, as well as explains the Dissociative Identity Disorder problem. The discursive production of selves differs greatly across cultures, which gives evidence that it does not exist in substance, otherwise the concept of self would remain the same across cultures. Harré and Gillett do assert that personal identity is a concept that is universal. Using the case provided by Prince, Harré and Gillett use the discursive viewpoint to explain how a single body could have several senses of selves. Miss Beauchamp had different personalities that appeared to be internal but with the discursive method, the situation can be viewed in a different light. It is not three selves competing for a voice; it is a person expressing three selves in discourse. By taking Harre and Gillett’s interpretation, we can reason that Miss Beauchamp had three different senses of personal identity. Each personality bound the components of personal identity differently.

To conclude Harré and Gillett’s theory, the sense of personal identity is experienced by the location of oneself, the relation to external objects and the sense of moral and social roles. This is revealed in the individual’s discourse. Language does not teach us how to perceive our location and relations, our perceptual and motor skills do. However, we express these perceptions through our pronoun usage regardless of the language. Our sense of agency is learned through our culture's moral expectations. Discourse is vital to understand human concepts of self and personal identity. The production of selves is constituted in discourse. Without discourse there can be no self, only a sense of personal identity with no ability to express it.

The distinction between the produced self and sense of identity can be further examined through observing species other than humans. American biopsychologist Gordon Gallup developed the “mirror test” in which the chimpanzee must look into a mirror and display behavior of self-recognition. By examining the results in his studies on chimpanzees we can observe the difference in between the self and sense of personal identity. In Self-Awareness in Primates: The sense of identity distinguishes man from most but perhaps not all other forms of life (1979), Gallup demonstrates how chimpanzees can recognize themselves in the mirror (418-419). He devised several tests to observe this. He studied the behavior chimpanzees displayed in mirrors. At first, the chimpanzees thought their reflection was another being, but after multiple times of being exposed to the mirrors they were able to recognize themselves. Gallup observed that the chimpanzees would use the mirrors to clean their teeth, clean their hair, and other activities that make sense only on the assumption that the chimpanzees recognize themselves in the mirror.

By taking these studies into account, we can see that the chimpanzees might have a sense of personal identity. They seem to exhibit some of the criteria, presented by Harré and Gillett that constitutes a sense personal identity (e.g., sense of location and time). However, the chimpanzees have no observable ability to produce a self in discourse. Their limited discursive abilities do not show the ability to express personal identity through production of a self. We have no absolute proof that the chimpanzees have a complete sense of personal identity. The ability to recognize oneself in the mirror could be just a sense of self-awareness. As Harré and Gillett describe, the sense of personal identity is a complex phenomenon. It requires more than just self-awareness. The chimpanzees display a sense of location and time in which their body exists. This is a remarkable feat, albeit they do not display the sense of agency or moral responsibility. In discourse, that is required for a sense of personal identity similar to a human’s. Therefore, we cannot say that they absolutely have a sense of personal identity but that they might have this sense. With the theoretical model of Harré and Gillett and Gallup’s findings, we can now look to additional sources to witness this distinction between sense of personal identity and the self.

The distinction of sense of personal identity and self-production can be further examined by the work of Raya A. Jones in The Presence of Self in the Person: Reflexive Positioning and Personal Construct Theory (1997). “Positioning theory stresses the contextuality, and understates the dynamics. Kelly’s theory of personal constructs stresses the dynamics, and understates contextuality. Put together, we may begin to formulate a more realistic theory” (Jones 469-470). Jones synthesizes Rom Harré’s positioning theory and George Kelly’s personal construct theory to better elaborate the existence of the self. Rom Harré’s positioning theory is an elaboration on the theory of self-posited in The Discursive Mind. Both Harré and Kelly’s theories deny the existence of self as an entity, and posit that it is a construct. They differ in the way that self is constructed. Harré's theory has the reflexive qualities regarding how people position themselves to discursively produce selves. There remain levels of positioning such as the relation of self to others and vice versa. Jones claims that Harré’s view can only work if the world can only be known by observing discursive activities (469). Harre’s positioning theory holds that the positioning of someone into their world is reflexive in that everything that they experience is related to their perceived self. These experiences form perceptual knowledge about the world, and these experiences are displayed through discourse and thoughts (i.e., private discourse). Jones asserts that if we observe the world in this manner then the meaning of selves cannot be understood (469). Harré’s theory focuses on the present moment and the context of the meaning of selves in discourse, but it overlooks the dynamics of relationships to all external phenomena.

Jones posits that this understatement of the dynamic relationships of external phenomena can be fixed by the proposal of George Kelly’s personal construct theory (469). Kelly’s idea is that we create constructs of our perceived world. The self, in this theory, is one of those constructs. These constructs are not necessarily based off of discourse. To a person, things are either self or non-self. Anything they do not align with they would consider not a part of their self-construct. Personal construct theory focuses on the relationships of the observer and the observed. It is larger than discourse; it focuses on dynamics in non-discursive contexts.

By combining aspects of all the theories discussed, an improved outlook on the distinction in between sense of personal identity and the self can be made. Harré’s positioning theory and Harré and Gillett’s theory of self succeed in describing how we create our self through discourse. However, the theories are limited insofar as they fail to recognize the dynamics of external phenomena that go into formulating this self. They also fail in recognizing the complete role of binding sense of personal identity and its effect on self-construction. Kelly’s personal construct theory succeeds in recognizing the role of binding sense of personal identity and its effect on self-creation. It recognizes that external phenomena allow us to bind our sense of personal identity into a self. However, it fails in showing how this self is created; it ignores discourse and its importance. Thus, we can see the importance of combining these theories together.

By examining Jones’ synthesis, we can see how Harré’s theory can be improved to better understand the distinction in between sense of personal identity and the produced self presented in Harré and Gillett’s theory. The combination of Harré’s and Kelly’s theories holds that the way one positions or constructs one’s self is through both discursive and non-discursive methods. Our dynamic relationships with external phenomena have an effect on our sense of personal identity and its binding in addition to our social relationships and private discourse. However, the produced self remains a product of discourse.

Without this discourse, the self cannot be created. While the sense of personal identity can exist without the self, the self binds the components of personal identity; it gives rise to the complete sense of personal identity. Harré and Gillett’s theory of self allows us to see how the self is created and how it binds the components of personal identity. Gallup’s findings allow us to see how sense of personal identity could exist without a production of a self. Jones critique of Harré’s theory allows us to see that the complete role of binding sense of personal identity requires dynamic relationships for self-production. The components of personal identity remain prior to self-production, but production of self gives rise to the sense of personal identity. It binds the components into a sense of personal identity which then, in turn, can construe the self. Neither sense of personal identity nor the self can exist as a physical entity. They are merely ways of categorizing our perception of the world.

Cover Photo: https://www.flickr.com/photos/familymwr/4929686567/