“The Hispanic [Identity] Challenge”: How Ethnocultural Identities are Challenged by American Society

By Nathalie Moreno

When immigrants move to the United States, they are searching for a better life than the one they were dealt. What they do not expect is the problems they will experience once doing so — especially problems within themselves. The issue of identity can affect Hispanic immigrants across all generations—first generation, meaning they were born in their home country; second generation, meaning they were born in America while their parents were not; and even the one and one-half generation, a newer term meaning they were born in their home country, but immigrated to the U.S. around the ages of six to twelve. Knowing what these terms mean puts into perspective just how many families are affected by cultural clashes. Cultural clashes occur when an immigrant’s birth country contradicts with the norms and/or traditions of the culture they are migrating to. I chose to research the topic of immigrant identity for two reasons: first, my own personal experience with feeling that I didn’t fully belong, therefore subconsciously rejecting my ethnocultural identity. Because of the circumstances around me, I feared that I would never fit into either of my communities: the American one, the Black one, or the Hispanic one. The lack of belonging was in terms of appearance, of language, and of where I grew up. I was always convinced I was not Latina enough, while in other areas I felt I would never be American enough—I still grapple with those insecurities today. The second reason I chose to focus on Hispanic identities is because the topic is often overlooked by the media. Using Sandra Cisneros’s 1983 novel The House on Mango Street Julia Alvarez’s 1991 novel How the García Girls Lost Their Accent, I will demonstrate how young Hispanic/Latino girls experience identity crises because of their two different cultures clashing.

Though many people talk about current issues surrounding the Hispanic community, nothing seems to improve. Conversation about the Latino struggle doesn’t just need to start, it needs to continue. I am a Black Hispanic woman, and with both my parents being born in the Dominican Republic, a second-generation immigrant. I am also a first-generation college student, as neither of my parents had the opportunity to finish college or even high school. I share this personal information because to understand how an ethnocultural identity affects people’s lives, it is important to understand what parts of the self make up such an identity. Oftentimes, Hispanic/Latino individuals in the U.S. experience identity trauma and crises due to being torn between two cultures: their Hispanic/Latino one and their newfound American one. Though the terms Hispanic and Latino are oftentimes used interchangeably or as one, they come from different origins. In his comic essay “You Say Latino,” Terry Blas explains that while the term Hispanic is about language, meaning people “from a country whose primary language is Spanish,”[1] Latino is about geography referring to all of the people from Latin America, specifically “everything below the United States of America, including the Caribbean.”[2] So, a Hispanic person can also be Latino, but does not have to be, and vice versa. But in the scope of my research, both Hispanics and Latinos face discrimination and identity struggles because of their heritage. Due to varying forms of rejection experienced by first, one and one-half generation, and second-generation Hispanics through the treatment of American society, they begin to reject themselves and their culture, putting their ethnocultural identities at risk.

Russian social scientists Irina Zakiryanova and Lyudmila Redkina describe an ethnocultural identity as a social construct, determined by not only a person’s self-image, but also the perception of the groups they do/do not belong to.[3] In simpler terms, someone’s identity is not only affected by the way they see themself, but also by the way others see them. Because ethnocultural identities are affected both by ourselves and others, that gives us the power to not only play a hand in who we become throughout our lives, but to shape who others become. Zakiryanova and Redkina examine ethnocultural identities through a psychological lens, using Henri Tajfel’s social identity theory to apply ethnic identity to society. They attribute a deeper sense of self-awareness to how we carve out our space in the world, writing that “a person’s awareness of his/her place in the social world is primarily due to belonging to a social group.”[4] So much of our lives and identities are affected by how we fit in with others—because oftentimes, how we fit in with those around us is a reflection of how we fit into our own bodies.

In my experience, ethnocultural identity is made up of two sides: familial values/views, and environmental factors. Familial values include how one was raised, what norms and practices were taught, and how we were taught to behave at home versus in other people’s company. It includes what foods are considered a normal breakfast, how we talk to and treat our family members—any part of us that wouldn’t be the same without the help of our families. The environmental factors that affect our identities come geographically: growing up in the city is very different from growing up in a suburb. These factors include who we grow up around, the friends, teachers, and other figures who inspire us to act the ways we do. The systems and laws in place make an impact as well: the state of the economic, education, justice, housing, and employment systems of our area. All these factors combined, the ones that are inherited from our families and the ones that we learn on our own, come together to create our ethnocultural identities.

These identities are plural. When Hispanic immigrants come to America, their ethnocultural identities expand and evolve. Now Hispanic/Latino individuals have to deal with an identity influenced by Hispanic culture, and one influenced by American culture. American sociologist W.E.B. Du Bois described it as a “double consciousness.”[5] In his work Souls of Black Folk, where he talks about the difficulty of being Black and American, he talks about this feeling of twoness as “two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings, two warring ideals in one [brown] body.”[6] Oftentimes, it’s hard to use the contrasting influences together instead of them fighting each other. The fight creates a cultural clash, and because of the overwhelming prominence of new American culture and society, Hispanic immigrant identities tend to be the ones on the losing end.

Cultural clash opens the Hispanic ethnocultural identity to many threats. The threats can be categorized into two areas I identified earlier (environmental and familial) – threats having to do with American society or familial/inherited circumstances. In terms of American society, the ethnocultural identities of the protagonists in both Alvarez’s and Cisneros’s novels are threatened by their economic class status, which includes whether they are belittled by others because of their class standing, as well as if they are ashamed of their class standing. These attacks include differences between American culture and their own heritage, such as whether they dress differently, eat different foods, and have different sounding names. And finally, hardships come from the geographical location of the Hispanic/Latino families as well. For all the protagonists, where they live and where they move throughout their lives, changes how they see themselves and how they are seen by those around them.

In the case of familial circumstances, sometimes our ethnocultural identities are threatened from right inside our homes. Moving from a foreign country to America can create a disconnect between gender roles within the family and those exhibited in society—especially when it comes to women. Adapting to new, conflicting cultures upon emigration is another point of contention: America, a very individualistic country, differs from many Hispanic/Latino countries that are very pointedly collectivistic, placing an emphasis on always putting family first. Finding a balance between the two is hard and can cause disconnect along the way. Finally, there’s the issue of outside influence—who we are with cultural outsiders versus those with a shared culture. For the protagonists and many young Latinos, there are instances where they think to themselves “why aren’t we more like them?” When the answer to that question is the way that we have been raised in our culture, there are feelings of resentment or anger at not having the same liberties as the girl next door.

The negative feelings all conspire together to become a larger issue: an identity crisis. An identity crisis can occur in two ways: when two parts of one person’s identity clash and when we reject one aspect of our identity for fear of it being undesirable to others or unwelcoming to us. This form of rejection is a result of “always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity.”[7] Identity crises can spiral, causing issues mentally, emotionally, and at the worst of times, physically. Building on the work of Du Bois, Gloria Anzaldúa writes about the emotional trauma that occurs in her cultural criticism book Borderlands/La Frontera, saying that “the ambivalence from the dash of voices results in mental and emotional states of perplexity. Internal strife results in insecurity and indecisiveness. The mestiza's dual or multiple personality is plagued by psychic restlessness.”[8] Here, Anzaldúa points out not only the mental and emotional strain put on someone with multiple cultural identities, especially when the multiple identities are new.

For political scientist Samuel Huntington, the answer to this crisis of identity is simple: we should force the Hispanic community to assimilate to Anglo-Protestant, that is, white, European culture and close our borders to all those who refuse. Huntington wrote a 2004 essay entitled, “The Hispanic Challenge,” a title that is itself a provocation to Hispanic/Latinos: he’s subliminally asking, as Du Bois felt himself and the Black race being asked, “How does it feel to be a problem?”[9] Originally published in Foreign Policy, the article focuses on six factors that make today’s immigration different from past immigration: contiguity, scale, illegality, regional concentration, persistence, and historical presence. The subheading of the article sets the tone for the entire piece, reading, “The persistent inflow of Hispanic immigrants threatens to divide the United States into two peoples, two cultures, and two languages.”[10] Just the categorization of Hispanic immigrants as a threat is contributing to the attack on Hispanic culture. Huntington even goes so far as to reference the country’s Founding Fathers, who “considered the dispersion of immigrants essential to their assimilation.”[11] Here he proposes the separation of Latino families from their communities, claiming, “the more concentrated immigrants become, the slower and less complete is their assimilation.”[12] Huntington comes up with many scenarios in which America and its citizens become bilingual. He argues against it because if “most of those whose first language is Spanish will also most likely have some fluency in English, English speakers lacking fluency in Spanish are likely to be and feel at a disadvantage…”[13] The hypothetical problem he speaks of is one Hispanics who are not yet perfectly fluent in English already experience daily. The problem for Huntington doesn’t seem to be monolingual people at a disadvantage; the problem seems to arise when those monolingual speakers are English speaking instead of Spanish. His solution to this seems to be isolation from one’s culture and language entirely, risking a total erasure of their culture. What for him seemed to be the worst horror of all, and worthy of mention, came true when “In 1998, “José” replaced “Michael” as the most popular name for newborn boys in both California and Texas.”[14] It is frightening that Huntington uses something so trivial as the most popular name for a newborn boy as a reason to attack a whole group of people.

Huntington’s main point in this piece is that American culture is white culture, and it must be protected from Hispanics. With Huntington arguing so persistently that Anglo-American culture needs to be saved, he seems to forget the values America was built on: giving all citizens the freedom to live as they choose, culture, language and backgrounds included. This idea has been used to manipulate people of color looking to find this freedom, and instead, “the American nation has been built on the exploitation and political exclusion of these [multiethnic] populations.”[15] It’s this view of Hispanic/Latino culture as a threat, as a problem, as a challenge, that causes Hispanic/Latino individuals to see that part of their identity as something to be fixed. Despite these lasting inequalities, there is still hope for change since “culture is the contemporary repository of memory, of history, it is through culture, rather than government, that alternative forms of subjectivity, collectivity, and public life [can be] imagined.”[16] Using the endless amount of cultures we can come to live with, or even a new culture we create out of the all the ones we know, would not be possible without the past and everything that has happened before now.

To effectively study these texts, I’ll be using a lens of intersectionality, a term coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989, meaning to take all aspects of one’s identity into consideration in conjunction with each other to understand the specific discriminations they face. Crenshaw describes it as “a lens, a prism, for seeing the way in which various forms of inequality often operate together and exacerbate each other.”[17] The overlapping identities for the main characters in García Girls, the García de la Torre girls and the protagonist of Mango Street, Esperanza are, of course, their Hispanic ethnocultural and racial identity and their gender identities as women. Using cultural studies, critical race theory, and gender studies, I will be looking at the novels through more of a theoretical lens.

To demonstrate how the Latinas witnessed these struggles but also overcame them, I’m going to use Sandra Cisneros’s The House on Mango Street and Julia Alvarez’s How the García Girls Lost Their Accent. Both novels were loosely inspired by the writers’s childhoods. The main characters of the novels struggle to find a way to make the transition between being a Hispanic and being an American, to being a Hispanic-American. Anzaldúa describes it as being on two opposite sides of a riverbank.[18] Throughout the novels, the protagonists are trying to leave the opposite bank and learn how to stand on both shores at once, be two identities at once. The young women in the novels are struggling to develop that mestiza consciousness, a consciousness that absorbs all cultures and acts as a “…product of the transfer of the cultural and spiritual values of one group to another.”[19] They are going through a “struggle of flesh, a struggle of borders, an inner war.”[20]

The House on Mango Street was originally published in 1983. This novel marked Cisneros’s first big break and still stands as one of the most important pieces of Chicana literature. The high praise is mainly due to Cisneros’s focus on a mixture of themes, which allowed Mango Street to become “a new kind of bildungsroman [coming of age novel]—one that features a marginalized character whose experiences of class, race, ethnicity, and gender are specific to her identity and development.”[21] The novel is centered around a young girl named Esperanza, who is growing up as a second generation Mexican-American in Chicago. However, even though Esperanza is the protagonist, Cisneros uses this novel to portray “a community of women who are isolated, abused, and trapped, [and] Esperanza learns from them by observing their situations and by listening to them.”[22] Because of their experiences, Esperanza sympathizes with the women but “realizes she wants a different kind of life; over the course of the book she develops into a strong, independent young woman who [is] able to find her own path.”[23] The realization is evident at the end of the novel, in the way that Esperanza leaves for years, only to come back and try to save those that did not have the same luck as her.

Julie Frankel, “The House on Mango Street by Sarah Cisneros”, via Flickr https://www.flickr.com/photos/readinginpublic/6342247835

Because of their lower-class status, Esperanza’s family moves a lot; Cisneros writes the story of when they move into the house on Mango Street. The family’s newest move proves to be a prominent point of contention for Esperanza; she spends most of her childhood waiting for a house to feel like a home. What she is really looking for is a place to feel comfortable enough to grow into the woman she’s learning to become, to formulate a new identity. Esperanza’s new identity, a mix of her Mexican, Chicana, and newfound Americanness, demonstrate how “individualistic and communitarian ideals not only coexist in Cisneros’s text without the one erasing the other, but also cross and overlap…”[24] Esperanza combining parts of all her past identities to become someone totally different is living proof that it can be done—if Americans stop attacking the very idea of a multi-ethnocultural identity.

In the beginning of Mango Street, Esperanza experiences an attack on her Hispanic name. Because of how others say her name, she herself sees her name as “made out of tin…,”[25] a metal easily cut and malleable, and hurting the roof of the white American mouth. This mispronunciation, the difficulty of saying something so important to one’s identity as their name is the first of many attacks on Esperanza and other members of the Hispanic community. In turn, Esperanza resents her name, concluding that “it means sadness, it means waiting. It is like the number nine. A muddy color. It is the Mexican records my father plays on Sunday mornings when he is shaving, songs like sobbing.”[26] She’s associating her name, which is supposed to mean something positive (translating to “hope”) with negative emotions, negative feelings that are paired with parts of her Mexican culture. What Cisneros demonstrates here is Esperanza internalizing the racism she experiences and, in turn, rejecting her culture.

Esperanza tries hard to make the house on Mango Street her safe space, but falters because of outside influences and comments like her supposed friend saying, “you live there?”[27] after she points out her house. She grows more and more distant from the house, until at the end when she fully rejects it, “No this isn’t my house I say and shake my head as if shaking could undo the year I’ve lived here. I don’t belong. I don’t ever want to come from here.”[28] What we’re seeing is Esperanza disassociating from her neighborhood, her brown neighborhood, because it’s looked down upon by her white friends. The othering is even more evident in a chapter titled “Those Who Don’t” where Cisneros writes, “Those who don’t know any better come into our neighborhood scared.”[29] There’s a very clear separation between white and brown in this chapter, but it also demonstrates the feelings Huntington is trying to elicit through his own essay: that we should fear communities we do not yet understand.

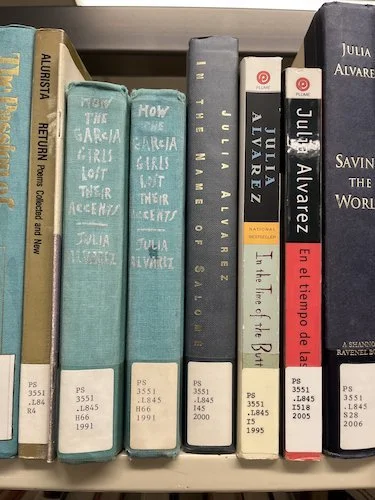

For Julia Alvarez in her 1991 novel How the García Girls Lost Their Accent, the story focuses on the García de la Torre family, specifically the four daughters Carla, Sandra, Yolanda, and Sofía, as they navigate going from upper class royalty in the Dominican Republic to living paycheck to paycheck in 1960s New York City. The daughters are coming into their own, embarking on a “search for identity motivated by a tense struggle between Hispanic and North Americans.”[30] Alvarez’s novel is popular and relevant today because of the focus on the (at the time) current events happening in the Dominican Republic, particularly about the reign of Rafael Trujillo. Alvarez also jumps around timelines, going backwards in time and events. She makes it so that “the beginning of the narration is the end and the end is the beginning [so] consequently the novel has two beginnings and two endings, physical and chronological ones.”[31] Each of the girls deal with different struggles, from difficulties with language to parental disobedience to white/American passing. The biggest evidence of their struggles with their new dual identities shows through their language struggles. Being born in the DR, all four daughters were raised with Spanish as their first language. In different settings of their lives, at school, in their neighborhood, even in romantic relationships, their native tongue is attacked, belittled into an abnormality. When meeting a boyfriend’s parents, Yolanda is spoken down to: “His parents did most of the chatting, talking too slowly to me as if I wouldn’t understand native speakers.”[32] Already the parents are assuming that Yolanda is not American enough to speak or understand English fluently. When she proves them wrong, they compliment her accentless English, implying that the erasure of an accent, of the language and of the culture is something to strive for.

Julia Alvarez, photograph by Valerie Hinojosa, September 25, 2009, via Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Julia_Alvarez_3967875650.jpg

This unwelcomeness is exhibited again when the eldest daughter, Carla, is walking home from school. She thinks about how she would respond to a passing car asking her for directions. Because she is the oldest child at the time of emigration, her English is not as far along as her younger siblings. And while Huntington would argue that she feels she doesn't belong because she’s not assimilating enough, the second part of the passage makes it clear that the way Carla is treated by others is the real culprit here. The quotation reads, “‘I don’t speak very much English,’ she would say in a small voice by way of apology. She hated having to admit this since such an admission proved the boy’s gang point that she didn’t belong here.”[33] The conclusion that she doesn’t belong comes hand in hand with the thought of the American boys at school who bully her for that exact reason.

Second daughter Sandi experiences a different type of belonging due to her physical appearance. Sandi is lighter than the rest of her family, with blue eyes from a Swedish grandmother. In this scene, young Sandi is just now realizing that, while she doesn’t entirely look like the rest of her family, she does look like the other white American girls. She finds that “looking at herself in the mirror, she was surprised to find a pretty girl looking back at her. It was a girl who could pass as American, with soft blue eyes and fair skin…”[34] In that moment, her thoughts of what an American looks like are singular and unchanging: white and blue eyed. Not long after this quotation she proceeds to say that “being pretty, she would not have to go back to where she came from. Pretty spoke both languages. Pretty belonged in this country.”[35] She has associated the idea of whiteness with being pretty, meaning of course that anything not white is not pretty and, therefore, does not belong in America. As Du Bois, Anzaldúa, Ortiz Cofer, and so many more could tell you, much of the reason Americans assume the ‘Other’ group does not belong is because we do not look like them. Even I have personal experience with this, having to sit through questions asking if I am adopted because I’m Black and my sister is white.

How the García Girls Lost Their Accents. Photo by Erin Delaney, 2023.

What they and other people fail to realize is that Hispanics can come in all skin tones, white passing or thought to be African in some cases; this is a big reason why the debate about making Hispanic/Latino a race exists today. In the two novels, the girls witness instances and feelings that have to do directly with colorism, a term that means racism towards those with darker skin tones. An example of this colorism is evident in Sandra from García Girls. She is fair toned and blue eyed, passing for white often. To her, this is a good thing. It means she’ll be able to distance herself from her family at any given time, whenever they are treated differently. Another experience of blatant racism is exhibited through the neighbor they nicknamed “La Bruja” shouting insults and slurs at them for no apparent reason. She yells things such as “Spics! Go back to where you came from!”[36] Because they dress, talk, look and even cook differently, La Bruja assumes that they do not belong, and they never will. There are also racial undertones in character descriptions, especially when they describe Chucha, their family maid in the Dominican Republic, saying, “Chucha was super wrinkled and Haitian blue-black, not Dominican cafe-con-leche black.”[37] The emphasis put on Chucha’s skin tone shows how much of a role race and skin color plays in the Hispanic community. It’s the first thing they mention introducing Chucha, and it’s the first independent realization Sandi comes to when looking at herself in the mirror. For them, the more you look like ‘them’ (the lighter you are), the better chance one has of being accepted.

Cultural studies was first established in the late 1950s and advanced by Robert Hoggart, Raymond Williams, and Stuart Hall. The theory “transcend[s] the confines of a particular discipline such as literary criticism or history…”[38] and looks at how culture relates ideology, nationality, ethnicity, social class, gender, sexuality, and more. A lot of Hall’s work has to do with the multiplicity or combination of culture and identity; for example, in his Cultural Identity and Diaspora, Hall asserts, “cultural identity...is a matter of ‘becoming’ as well as ‘being’. It belongs to the future as much as to the past. It is not something which already exists, transcending place, time, history, and culture. Cultural identities come from somewhere, have histories. But, like everything which is historical, they undergo constant transformation.”[39] Hall’s description of a cultural identity reflects how Cisneros and Alvarez talk about their characters. For example, Esperanza is no longer content just being, she looks for an opportunity, a space where she could become who she is meant to be.

In terms of gender, both Cisneros’s and Alvarez’s texts rely heavily on the gender roles and perceptions of a Hispanic woman in particular. Both these texts were loosely inspired by the childhoods of their respective writers. Another thing these works had in common was the theme of breaking from family tradition. I specifically chose works written by Latinas because Hispanic men and women, while they go through a lot of the same discriminations, face different obstacles due to their genders or lack thereof. For Hispanic women in their home country and in the U.S., the roles and expectations are clear: stay-at-home mother, family caretaker, never go outside alone, clean up after yourself and everyone else. While some Latina stereotypes line up with female expectations everywhere—like the doting cooking and cleaning housewife—other stereotypes contrast actual gender roles set for us.

In her essay titled “The Myth of the Latin Woman,” Judith Ortiz Cofer talks about how people have “designated ‘sizzling’ and ‘smoldering’ as adjectives of choice for describing not only the foods, but also the women of Latin America.”[40] This stereotype is perpetuated by the way Latinas dress to impress, with lots of jewelry and accents, which many mistake as an attempt at being seductive or flirtatious. However, this stereotype conflicts with one of the gender roles expected of Latinas: that of modesty, chastity, and religiousness. A prime example of the two conflicting ideals appears in García Girls, when a boyfriend of Yolanda’s says, “I thought you’d be hotblooded, being Spanish and all, and that under all that Catholic bullshit, you’d be really free...But Jesus, you’re worse than a fucking Puritan.”[41] Due to influences from the American culture that surrounds them after emigrating to the US, protagonists in each of the novels break away from those collectivist and sexist ideals that were originally instilled upon them, rejecting their ethnocultural identities further.

Esperanza becomes influenced by her classmates, seeing the ways they are given more freedom to dress how they want, go wherever and with whoever they want. In a childlike act of rebellion, Esperanza begins her “own quiet war.” In her own words, she says, “I am the one who leaves the table like a man, without putting back the chair or picking up the plate.”[42] As is traditional for Hispanic families, Esperanza is used to the patriarchal authority of her family, the idea that “the men are the head and the boss of the family.”[43] In Esperanza’s mind, whether she’s speaking figuratively or literally, leaving the table ‘like a man’ is her way of putting aside her inherited beliefs and asserting her dominance, taking a piece of the power she sees that the men in her life and other American women have. This aspect of the novel is reflective of Cisneros’s own childhood, where she felt she was slipping through the cracks of her six older brothers. She recalls going out with her father, and when he would talk to bystanders and brag about his seven sons; “I could feel myself being erased and would tug my father’s sleeve and whisper: ‘Not seven sons. Six! and one daughter.”[44] The favoritism Cisneros witnessed her father take toward her brothers and the ways she acted out is reflected in how Esperanza rejects the gender roles put on her, even at such a young age.

Sandra Cisneros, December 2, 2017, via Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sandra_Cisneros_%2823929672797%29.jpg

For the García girls, they claim their independence in different ways. For youngest daughter Sofía, it meant running away and getting married without her father’s blessing. For Yolanda, it was as simple as going on a road trip alone, not having to rely on a man’s presence to feel safe. On a return trip to the Dominican Republic, Yolanda applies her new confidence and freedom gained from living in the U.S. for years. When told she should bring a man along on her trip, she lets the “mighty wave of tradition roll on through her life and break on some other female shore. She plans to bob up again after the many don’ts to do what she wants.”[45] This is Yolanda’s way of showing her independence and dominance, making clear that she can take care of herself and does not need a man’s help to survive. Both these passages demonstrate ways in which the women in the texts—and most likely the women behind the texts, as well—broke from tradition and began carving their own way, creating a new definition for what it means to be a Hispanic-American woman. In an interview, Sandra Cisneros talks about what Esperanza was going through throughout The House on Mango Street. She says Esperanza was looking less for a physical home, and more of a metaphorical one, somewhere she could “create a space for her to reinvent herself, another way to be other than what [she inherits] from our culture.”[46] All the young Latinas portrayed in both novels are just trying to find another way to be, or as feminist writer Rosario Castellanos puts it, “otro modo de ser.”[47]

The important thing to remember about both novels is that in the end, the young Latinas turn out alright. For Esperanza, while she did reject the space she was living in at the time and left Mango Street, she came back. The benefits of her collectivistic nature still co-existing with the individualistic tendencies she learned in the U.S., Esperanza was able to make it out of her hometown, saying, “One day I will say goodbye to Mango. I am too strong for her to keep me here forever.”[48] Esperanza broke free of tradition, making a new path for herself where she could leave the expectations and stereotypes behind to become her own person. However, Mango Street is also about community. Though Esperanza leaves, she promises to come back “for the ones [she] left behind. For the ones who cannot out”[49] as easily as she can. This is her promise to Sally, to Meme, to Nenny, to her mother. She is promising she will not forget them, forget her home culture and tradition, after she ventures off into the new world.

For Yolanda, Carla, Sofía, and Sandra, their moments of realization came at different times in the novel. Because Alvarez wrote the timeline backwards, starting from the end, the four girls had already grown up and found themselves when the book began. Yolanda was proving to herself and her family that she could do things on her own and without the help of a man, Sofía had followed her heart and broken the religious expectations set by her father, Carla had to learn the American ‘way of life’ on her own, and Sandra came to terms with what it means to look different from your family but similar to the ones othering you. These girls also returned to where they came from—in more ways than one. Yolanda returns to the Dominican Republic as an adult, with the intention of moving back there permanently because “She has never felt at home in the States…”[50] For her, her path was returning to her home country, but this time, with new skills and characteristics learned in the States. For Sofía, returning to her roots meant forgiving her father for their falling out, accepting that there is room in her life for both tradition and spontaneity. All these girls found ways to live out their dreams, leaving all they knew behind and taking it upon themselves to create new identities.

Applying the issue of Hispanic discrimination to recent real-world statistics puts things in an unfortunate light. During the 2020 election, there was an uproar about building the wall on the Mexican border proposed by Donald Trump, as well as all the children separated from their families by ICE. In 2021 alone, “a record 122,000 children were taken into U.S. custody without their parents.”[51] As of 2020, Hispanics make up about 19 percent of the American population, amounting to about 62 million Hispanics.[52] Huntington and American society’s attack on Hispanic ethnocultural identity bleeds into lawmaking, government decisions, and systems needed to survive, namely, the employment, housing, education, judicial, medical care systems. 31% of Latinos experience discrimination in the workplace by non-Hispanics. This includes Hispanics being criticized for speaking Spanish, being told to go back to where they came from and being treated as unintelligent. Hispanic renters are 49% less likely than white families to hear back about a property listing. Only 11% of Hispanics over 25 years old have a bachelors’ degree, making them statistically “the least educated group in the United States…”[53] While these are Hispanics who have been “accepted” into America, most likely in the way of gaining citizenship, the change cannot end there. Although Latinos have been superficially accepted into the US, “these struggles have revealed that the granting of rights does not abolish the economic system that profits from racism.”[54] The aforementioned statistics are just pieces of the overwhelming evidence that Hispanic/Latino identities are not welcome in the US.

Thomas Hawk, “This is a Country of Immigrants”, via Flickr https://www.flickr.com/photos/thomashawk/138586889/in/photostream/

By continuing to make Hispanic/Latino ethnocultural identities unwelcome in the U.S., we are contributing to the blatantly obvious problems already existent in the country. The experiences of the growing Latinas in Sandra Cisneros’s The House on Mango Street and Julia Alvarez’s How the García Girls Lost Their Accents against discriminations like the ones present in Samuel Huntington’s The Hispanic Challenge is the perfect example of the attack on Hispanic ethnocultural identities. It’s time to give up the idea that American culture is set in stone: white, cisgender, heterosexual, and English-speaking. Huntington asks his audience, “Will the United States remain a country with a single national language and a core Anglo-Protestant culture?” The answer is no. In fact, that has never been true. Instead, those white, cisgender, heterosexual, and English-speakers have only been the ones with power. Now that Hispanics have a growing power in numbers, the American culture Huntington believes in is at risk—to that I say, good riddance. It’s time to open doors and make room for a new culture: one where dual ethnocultural identities are not attacked but accepted. The possibilities truly are endless once we start acting and stop reacting.

Endnotes

[1] Terry Blas, “I’m Latino. I’m Hispanic. And they’re different, so I drew a comic to explain,” Vox, August 19, 2015, https://www.vox.com/2015/8/19/9173457/hispanic-latino-comic.

[2] Blas, 2015.

[3] Irina Zakiryanova and Lyudmila Redkina. “Research on Ethnocultural Identity in H. Tajfel’s Social Identity Theory and J.C. Turner’s Self-Categorization Theory,” SHS Web of Conferences 87 (2020): 2, https://doi.org/10.1051/shsconf/20208700103.

[4] Zakiryanova and Redkina, 3.

[5] W.E.B Du Bois. The Souls of Black Folk, “The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Souls of Black Folk, by W. E. B. Du Bois,” (Chicago, A.C. McClurg & Co., 1903), chap. 1, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/408/408-h/408-h.htm.

[6] Du Bois, chap. 1.

[7] Du Bois, chap. 1.

[8] Gloria Anzaldúa, Borderlands/La Frontera (San Francisco: Aunt Lute Book Company, 1987), 78.

[9] Du Bois, chap. 1.

[10] Anzaldúa, 30.

[11] Anzaldúa, 35.

[12] Samuel Huntington, “The Hispanic Challenge,” Foreign Policy 141 (2004): 35.

[13] Huntington, 40.

[14] Huntington, 38.

[15] Lisa Lowe, Immigrant Acts: On Asian American Cultural Politics (Durham: Duke University Press, 1996), 23.

[16] Lowe, 22.

[17] Katy Steinmetz, “She Coined the Term ‘Intersectionality’ Over 30 Years. Here’s What It Means to Her Today,” Time, February 20, 2020, https://time.com/5786710/kimberle-crenshaw-intersectionality/.

[18] Anzaldúa, 78.

[19] Anzaldúa, 78.

[20] Anzaldúa, 78.

[21] Amy Sickels, “The Critical Reception of The House on Mango Street,” in Critical Insights: The House on Mango Street, edited by Maria Herrera-Sobek (Hackensack: Salem Press, 2010), 44.

[22] Sickels, 46.

[23] Sickels, 46.

[24] Stella Bolaki, “This Bridge We Call Home: Crossing and Bridging Spaces in Sandra Cisneros’s The House on Mango Street,” in Critical Insights, edited by Herrera-Sobek, 213.

[25] Sandra Cisneros, The House on Mango Street (New York: Vintage Books, 1991), 11.

[26] Cisneros, The House on Mango Street, 10.

[27] Cisneros, The House on Mango Street, 5.

[28] Cisneros, The House on Mango Street, 106.

[29] Cisneros, The House on Mango Street, 28.

[30] William Luis. “A Search for Identity in Julia Alvarez’s How the Garcia Girls Lost Their Accents,” Callaloo 23, no. 3 (2000): 840.

[31] Luis, 840

[32] Julia Alvarez, How the García Girls Lost Their Accents (Chapel Hill, N.C: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 1991), 100.

[33] Alvarez, 156.

[34] Alvarez, 181.

[35] Alvarez, 182.

[36] Alvarez, 171.

[37] Alvarez, 218.

[38] Nasrullah Mambrol, “Cultural Studies,” Literary Theory and Criticism, November 23, 2016. https://literariness.org/2016/11/23/cultural-studies/.

[39] Stuart Hall, Identity and Diaspora (Durham: Duke University Press, 2019), 225.

[40] Judith Ortiz Cofer, “The Myth of the Latin Woman,” Beacon Broadside: A Project of Beacon Press, accessed by November 15, 2022. https://www.beaconbroadside.com/broadside/2020/10/the-myth-of-the-latin-woman.html.

[41] Alvarez, 99.

[42] Cisneros, The House on Mango Street, 89.

[43] Geri-Ann Galanti, “The Hispanic Family and Male-Female Relationships: An Overview,” Journal of Transcultural Nursing (2003): 183.

[44] Sandra Cisneros, “Only Daughter,” in Latina: Women’s Voices from the Borderlands, edited by Lillian Castillo-Speed (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1995), 159.

[45] Alvarez, 9.

[46] Sandra Cisneros, “The House on Mango Street – The Story,” video, 00:20, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0Pyf89VsNmg.

[47] Sandra Cisneros, “The House on Mango Street – The Story,” video, 00:20.

[48] Cisneros, The House on Mango Street, 110.

[49] Cisneros, The House on Mango Street, 110.

[50] Alvarez, 12.

[51] Erica Bryant, “Children Are Still Being Separated from Their Families at the Border,” Vera Institute of Justice, Jun. 23, 2022, https://www.vera.org/news/children-are-still-being-separated-from-their-families-at-the-border.

[52]Mary Findling, “Discrimination in the United States: Experiences of Latinos,” Health Services Research 54 (2019).

[53] Barbara Schneider, Barriers to Educational Opportunities for Hispanics in the United States (National Academies Press, 2006.)

[54] Lowe, 26.