Free Thought, Free Will, and Freedom Projects: A Study of Religious Resistance

Hannah Davies

The American Constitution grants citizens freedom of speech and freedom of association. Collectively, these rights recognize citizens’ ability to protest the American Government. From the inception of the United States, direct-action protests have been a cornerstone of American democracy. Direct-action protests are so well renowned and embedded into the fabric of American democracy that in-direct protests have failed to gain the same level of traction and immortalization. This essay examines the validity of indirect small-scale resistance when conducted by liturgical (i.e.: Catholic and Episcopalian) and non-liturgical (i.e.: Baptist and Methodist) churches and the historical background that predated resistance modes and church influence during the Civil Rights Movement.

Library of Congress’ Caption: African American demonstrators outside the White House, with signs "We demand the right to vote, everywhere" and signs protesting police brutality against civil rights demonstrators in Selma, Alabama 1965.

Introduction

“Negros should spend more time praying and less time demonstrating” was a statement in a 1964 survey entitled Negro Political Attitudes. Of all the Black respondents surveyed, 458 agreed with this statement, 571 disagreed, and 8 said there was no difference.[ii] This close split in respondents’ opinions highlights the differences in perceptions of the value and success of demonstration in securing Civil Rights. Additionally, this split further highlights that the efficacy of liberation theology in protecting and securing the Civil Rights of Blacks in America was another contentious issue that divided many Black Americans. Furthermore, those surveyed were also asked, “Do you think Negroes are better off in the South, in the North, or isn't there any difference?” Here 533 respondents said that things were better off in the North, while 330 saw no difference, and 171 saw the South as better off.[iii] While more people overwhelmingly voted for the North as the more ‘ideal’ location, this may have been a result of the more overt racism and disenfranchisement that occurred in the South paired with the hyper-visibility of the bombings and riots in Birmingham, Alabama, just a year earlier (1963). Historically, Northern complacency or active participation in segregation is often overshadowed by the acts of blatantly racist Southern policies. However, this essay will address the unique plights faced by Black Americans in both regions and how the role of the different churches was directly influenced by the religious history and culture as well as the regional concerns/experienced affronts to civil liberties. This essay aims to reframe how popular memory constructs the Civil Rights movement. Typically, when the Black church is referred to, it is the Black protestant church, and this neglect or erasure removes the experiences of those involved with the Catholic or Episcopalian church. Additionally, when the Civil Rights movement is typically studied, it is done under the guise of a direct-action campaign. However, the exclusion of non-protestant Black Christians and other forms of collective action falsely conveys that Black Americans are a monolith whose problems only require one type of solution. So, by re-incorporating the efforts of liturgical Blacks, this essay asserts that resistance modes were directly determined by church structure and regional cultures.

Denominational Differences Among Christian Churches: Liturgical vs Non-Liturgical

A Liturgical Church is typically defined as a church that has a “prescribed ritual of language and action”; thus, identifying the Catholic, Episcopalian, and Lutheran churches as liturgical. Denominations without “authority ordained worship or codified worship” typically refer to non-liturgical churches such as the Baptist, Methodist, and Presbyterian Churches. [iv] This paper primarily compares two liturgical churches: Catholic and Episcopalian, and two non-liturgical churches: Baptist and African Methodist Episcopal/Methodist. Additionally, to make the analysis more granular, emphasis is placed upon African American religious life with a keen eye on the Black Church.

William L. Breton. Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church, Philadelphia. Pennsylvania United States of America Philadelphia, 1829. Philadelphia: Kennedy & Lucas's Lithography, -07. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2021670179/ [vi]

The Black Church’s symbolic and embodied significance lies in the congregation and leadership belonging to the African American community.[vii] Given their significance and demographics, churches with a Black majority or who solely had Black congregations had an element of self-determination and Black culture that was embedded into the sermons and church culture. Astutely, Sister M. Martin de Porres Grey asserts that, historically, the Black Church, specifically the “Black Protestant Church” (a non-liturgical church), “is the only institution within the black community that Black people own and control.” The autonomy experienced by the protestant church “is not true of the Catholic Church'' and other liturgical churches in the black community.[viii] The creation of the Black Church in the South and in the North slightly differ but converges on two underlying themes of (ethnic) separation and self-determination as by-products of strong religious communities.

Outlining Resistance and Protest

There is a long-standing myth that Black Catholics were not a part of the Civil Rights movement. This myth is reflective of a larger trend that ignores Black Christianity if it is not in the form of Protestantism. Recently in 2021, a PBS documentary entitled The Black Church also fell into this tradition of ignoring Black Catholicism by briefly mentioning a few significant parishes and figures throughout a four-hour-long venture.[ix] Black Catholics and Episcopalians were active participants in the Civil Rights Movement. However, the ways in which liturgical churches resisted often differed from those of non-liturgical churches, and these differences added another dimension to the resistance movements in the 1960s. Given that their resistance did not involve direct action, their accomplishments have been largely belittled and disregarded as nonexistent. Cornell Law School’s Legal Information Institute defines protest as “an instance of civil resistance, or nonviolent resistance when it is part of a larger systematic and peaceful nonviolent campaign”.[x] Simplified, this definition includes any form of protest as a means of civilian resistance. Consequently, the efforts to reform the American Catholic or Episcopalian institution were a form of resistance and the Black Anglican efforts to do so contributed to the Civil Rights Movement. Liturgical churches are often perceived as more reserved and less engaged socially/civically due to their strict and hierarchical nature; however, said structure also provides unique opportunities to reform a large, internal, centralized system at once. Conversely, these efficient processes and broad frameworks are not available to Baptist or Methodist churches due to their autonomy and non-hierarchical structure that grants power to local churches.

Library of Congress’ Caption: Woodville, Greene County, Georgia. Church service in the Negro church [xi]

As mentioned previously, Liturgical churches’ preferred mode of resistance was primarily done internally due to the immense hierarchies and systems that enabled large-scale internal reform. Additionally, Liturgical churches focused primarily on internal development/growth (EX: leadership conferences, support groups, incorporating the idea of what it meant to be both Black & Catholic), and these psychological and institutional efforts are a form of protest that is inherently political. In fact, it is just as political as direct-action protests. Consequently, this paper will reframe protests as acts of resistance. Resistance can be characterized in two ways: small-scale and large-scale resistance.[xii] Small-scale resistance should be evaluated with a set of lenses that focuses on the human body and its reaction to the exploitation it experiences. According to Stephanie Camp, the study of the human body itself can be a study in resistance as “for people who experienced oppression through the body, the body becomes an important site of not only suffering but also resistance, enjoyment and potentially transcendence.” [xiii] With this framework, the unit of analysis is more individual, and transgressions are more personal. These acts of injustice that are imposed upon black bodies are so personal because, as stated by Camp, “[the body] was also a political entity, a site of both domination and resistance.” [xiv] Similarly, aside from brutish attacks on the human body, mental attacks should also be looked at with the same degree of scorn as the imprisonment or infantilization of the mind is immeasurably more devastating than any bodily affliction. On the harm of ‘mental prisons’, Pauli Murray, an American civil rights activist, and Episcopalian priest, stated, “Not only is the doctrine of separate but equal facilities a delusion but positively its effect is to do violence to the personality of the individual affected”.[xv] So, in this way small-scale resistance works to unchain the mind’s shackles and provide free thought and free will, which inevitably leads to the protection of the body. This shows that small-scale resistance’s characterization of individual actions, subtle inefficiencies, and internal changes are measures that can contribute greatly to a social cause but are often overshadowed by large-scale resistance. This definition, established as a paradigm for analysis by Historian Eugene Genovese, works well in the context of describing enslaved people’s resistance in the Antebellum South. In the context of the Civil Rights movement, defining small-scale resistance as unorganized and solely rooted in individual effort may not be true. A more modernized definition of ‘small-scale’ and ‘large-scale’ resistance, separated from the context of slavery, would define small-scale as ‘subtle, inward facing, and mobilizes the few’, and large-scale as ‘overt, outward facing, and mobilizes the masses.[xvi]

Historical Background: Early America’s Legalized Disenfranchisement and Dehumanization

Part of the “Old South'' or its mythology involves strong religious imagery. In contrast to popular belief, the religious indoctrination of the enslaved did not occur en masse until the advent of the Second Great Awakening. This protestant religious revival occurred all over the country in the early 19th century. From 1790-1830, religiosity, Christianity in particular, among the enslaved, was no longer seen as a potential threat. Instead, the enslaved were “cordially welcomed to the services and in many instances they [were a] considerable part of the congregation.”[xvii] Remarkably in the North, the first autonomous and independent Black congregations predated this change.[xviii]

For instance, St. Philip's was an Episcopalian Church in New York whose Black congregation “attended separate services at Trinity Church (a predominantly white church) and decided to become independent in 1809”.[xix] Rather than continue to attend segregated services, Black Episcopalians/parishioners “demanded their rights to full participation”; however, as claimed by Craig Townsend this demand is just as much an act of self-determination by African Americans as it was the “White leaders’ enforcing of their hierarchy.” [xx] Significantly, St. Phillips, one of the first Black Episcopalian congregations in the United States, was created nine short years before slavery was abolished in New York. Black religious life in the North was characterized by an early level of blatant autonomy that was unmatched by the Black experience in the South. Unfortunately, this freedom was not without struggle. Townsend noted that there was a “Paradoxical struggle for autonomy, and independence as a black congregation, [and] acceptance by a white denomination”.[xxi] In this growing age of segregation, Whites often saw Black Anglicans as “Nuisances”. Many White Anglicans felt that “working among the colored people would ruin their influence among White people of any clergy; do[ing] more harm than good.” [xxii] Due to the growing hostility, the creation of separate churches was necessitated in order to ensure the safety of Black members. Consequently, scholars like Townsend, do not see this change as a function of resistance, but one of survival. However, Black clergy and church's efforts to retain autonomy in any form is an act of resistance. Indeed, the actions that the St. Phillips congregations took should be seen as one of the Black Churches' earliest and most organized steps toward self-determination. Presumably, this early move for self-determination on the part of the liturgical church shows one of the earliest examples of the liturgical Black Church finding solace, empowerment, and resisting through the creation of their own institutions; despite being ignored or delegitimized by whites at every turn. Significantly, it is at this time that the Anglican church became the predominant denomination in the North for Blacks while its presence steadily declined in the South.[xxiii]

An abridged regional history of the South might include a focus on the South’s active participation in the institution of slavery, creating and enforcing Jim Crow laws, and mass lynching, whereas an abridged regional history of the North might focus on indirect participation in the institution of slavery, economic disenfranchisement, silent or codified racism. Collectively, these unique histories created the bedrock for the South and North to have similar yet entirely different historical and economic realities for Black Americans in 1960.

Library of Congress’ Caption: The renovated Greyhound bus station in downtown Jackson was the site of 1961 Freedom Rides, where activists protested segregated bus stations. [xxiv]

Freedom Summer

The aims of various civil rights movements directly correlated with the national, but more importantly, the regional and local issues faced by communities. Therefore, the unique struggles faced by Black Americans in the North and South, while similar, were also quite different, and the influence of the church also varied. According to Mississippian Civil Rights activist Winson Hudson, “Mississippi became the first state to impose a literacy requirement as a precondition to voting. Coupled with outright violence and intimidation, this measure would overturn the political gains made by Blacks after slavery”.[xxv] Mississippi’s disenfranchisement of Black Americans was not only codified but also a social expectation that was continually sustained. However, one of the most successful counterattacks to voter disenfranchisement and intimidation occurred in 1964 during what is known as ‘Freedom Summer’.[xxvi]

Succinctly put, Freedom Summer was a voter registration project created by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) aimed at increasing Black voter registration and turnout. Some of the more noteworthy associated projects that attacked civil disenfranchisement include Freedom Rides, Freedom Schools, and more. Lawrence Guyot, the former chairman of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party and a director of the Freedom Summer Project in Hattiesburg Mississippi, spoke highly of the National Council of Churches' (NCC) involvement in Freedom Summer. Lawrence Guyot went so far as to say that the NCC had “sent a representative from every major religion. You name a religion, it had a representative in Hattiesburg”.[xxvii] Guyot’s statement that every religion had a representative that was present in Freedom Summer, directly contrasts with the false narrative of the Catholic or Episcopalian church being passive actors in the 1960s. Guyot believed that the National Council of Churches was a powerful ally that “opened a lot of doors” that he believed “couldn’t open.” One of the ‘doors’ he referred to be a meeting with former president General Ford. He stated that “me and James Forma, got in to see the president that replaced Nixon, because his bishop told him to see us. And he made it clear that his bishop had told him, and he does what his bishop says”.[xxviii] To Guyot, the church, not any denomination in particular, was an extremely influential force that mobilized powerful people both directly and indirectly. This rhetoric of multiple denominations, clergy, and churches elevating the Civil Rights movement in Mississippi is echoed by James Breeden. In an interview, Bredeen described his involvement in the Episcopal Society for Cultural and Racial Unity (ESCRU).[xxix] According to Bredeen the ESCRU comprised laymen and clergy members who sought “to call attention to racist, segregationist behaviors of the church.…connect with and support--in support of activities in the Civil Rights Movement.” His involvement in the Mississippi Freedom Project occurred due to “…One of [my] ESCRU colleagues phoned me and said, "Would you be interested in going on a Freedom Ride?”[xxx] This quote directly contrasts the notion that liturgical groups did not engage in direct action resistance.

Additionally, the Episcopal Society for Cultural and Racial Unity not only endorsed Freedom Rides and other forms of direct-action protest but also aimed to eliminate single-race parishes and encouraged integration. Likewise, the ESCRU worked to end racial admission criteria in schools, camps, hospitals, and other spaces affiliated with the Episcopalian church.[xxxi] While many white, southern Episcopalians were against the creation of the ESCRU and what it stood for, its advent marked a significant shift in Episcopalian action and activism. This shift is significant because seven years earlier, in 1952, a study showed that Episcopalians were generally very socially conservative, and “10 percent of bishops and priests and 25 percent of lay people believed in the validity of segregation”.[xxxii] Here, the endorsement of large-scale protests like the Freedom Rides can be seen as the church’s support of large-scale protests. Additionally, their efforts to transform the church from within can also be seen as small-scale resistance.

Hearkening back to the small-scale vs large-scale resistance debate, Freedom Rides and mass voter registration efforts should be seen as examples of large-scale resistance. They should be categorized as large-scale resistance due to their overt, public, and outward-facing nature. Conversely, efforts like Freedom Schools are undeniably a form of small-scale resistance due to its internal focus on cultivating the Black community. Freedom Schools and the work of the volunteers were unique as they informed students about poverty and black conditions in the North vs. the South, and “introduced black history for the first time to many children”. Freedom Schools also informed locals on their “right to vote and of federal programs available to them,” and volunteers often “performed other tasks based on [community needs].” [xxxiii] In describing his experience volunteering and photographing the Freedom Schools, Herbert Randall states:

When the Freedom Schools began, you'd see children and their body language would be…kind of down or whatever. I would say maybe two to three weeks of going to Freedom Schools and just interacting with different things that they've never interacted with before. You'd know that people--that they can be educated, not a problem, not a problem, and why is it a problem? But that's another, it's a whole new, new, new thing.[xxxiv]

Randall’s sentiment effectively shows that, while the Freedom Schools did provide tangible information for their pupils, perhaps their most important output was exposure and an opportunity for Black American children to transform their minds. This is significant as Mississippi was one of the few states that did not have a compulsory education law, and as a result, many African American children’s educational schedules revolved around the agricultural calendar. Furthermore, for those that were in school, “the schools were woefully under-educating the kids. They were woefully inadequate”.[xxxv] So, similarly, just as SNCC created Freedom Schools as a form of small-scale resistance through re-education, the liturgical churches created various organizations and events to ‘re-educate’ or ‘re-imagine’ themselves and their spaces.

Liturgical Churches: Reeducation & Mental Transformation as a Form of Resistance

The liturgical effort to re-educate themselves was truly their attempt at redefining what it meant to be both ‘Black’ and ‘Catholic/Episcopalian’ as in decades prior, the role of Black clergy was limited. The limited role of Black clergy can almost entirely be attributed to prejudice and the creation of segregated parishes with limited power. Additionally, the limited role of Black Clergy can also be attributed to the rigid nature of liturgical churches' laws and rules. For many White Anglicans, Black Anglicans were often seen as “nuisances,'' and many felt that “working among the colored people would ruin their influence among White people of any clergy; do[ing] more harm than good.” [xxxvi] So, reevaluating and rehabilitating the image Black clergy had of themselves was done in multiple phases. One of the first was through the creation and incorporation of Black culture into religious imagery and worship, the creation of spaces for Black clergy, and an ideology or form of religious interpretation and preaching that aptly addressed Black Christians’ unique past and concerns for the future.

Library of Congress’ Caption: Mass at a Negro Catholic church on the South Side. Chicago, Illinois [xxxvii]

Regarding the importance of religious imagery, the First African Methodist Episcopal Church of Los Angeles (FAME) provides a great case study. In the late 1960s, the First African Methodist Episcopal Church in LA featured Black biblical and famous Black leaders on its stained glass. The former senior pastor, Reverend Cecil L Murray, stated that the church tried to “Change the ethos of the time” by making its Black congregation “see the glory in ourselves.” [xxxviii] Perhaps seeing God’s will and his likeness in oneself, for Black Christians, should be considered as a form of therapy that provides value to a group of people who have been devalued and dehumanized throughout time. Seeing Blackness in God is important for Black Christians because it “affirms you as one who was created in God's image and in God's likeness”.[xxxix] The creation of the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965) and the publishing of their guiding principles was groundbreaking for Catholics, as it ushered in a new age of reformed rules and ideals for the Roman Catholic Church that empowered lay people, engaged congregations, encouraged active prayer, religious freedom, and more.

For Black Catholics, the Second Vatican Council was even more transformative. Black Catholics interpreted the Second Vatican Council’s principles as a call to integrate African American culture and religious practices into Catholic Mass.[xl] This effort was predicated on the rising influence of the Black Power Movement, Dr. Matthew Cressler, notes that this new sense of merging black nationalism with Catholicism was defined by the context of a new more radical wave “[black] self-determination, cultural nationalism, and racial consciousness.” [xli] In describing how this change affected congregations all over the world, Bishop Joseph Howze emphasizes that significant effort was exerted to remind people that the blending of a congregation’s ingenious culture was “good, and not anti-Catholic”. For Black Americans this was manifested, as per Howze, through the adoption of Black spirituals, “...every, every Catholic Church has a gospel choir now, I mean black. And it is really, really traditionally a black congregation singing”.[xlii] For Bishop Howze the Second Vatican Council was revolutionary all over the world due to its language changes. The Second Vatican no longer required instruction in Latin and priests could instead instruct in local languages. This change among many others, helped usher in a new wave of intertwining culture with Catholic liturgy. The African-Americanization of Catholic mass made Catholicism all the more socially/spiritually accessible. This mental shift among Black Catholics, which enabled them to recognize that neutrality does not equate to ‘whiteness’ or that the incorporation of cultural elements to enhance worship, is perhaps the ultimate form of resistance when used against a religion that by and large delegitimized or patronized its Black clergy and members.

Regarding internal development, The National Black Sisters' Conference (NBSC) is the perfect example of the Black liturgical church engaging in small-scale resistance through internal transformation and community uplifting. The NBSC was founded in 1968 in Pennsylvania for lay and clerical African American women to support and educate one another. These conferences had workshops dedicated to educational growth, cultural enrichment, prayers, and health. [xliii] Sister Patricia Ralph described her time at a conference as “absolutely beautiful….to see so many African American Catholic women in one place”.[xliv] With workshops that focused not only on community development but also on the development of an individual, a unique focus was given on individualized resistance through spiritual and mental transformation.

Library of Congress’ Caption: Sisters of the Holy Family, New Orleans, La. [xlv]

Tellingly, the National Black Sisters’ Conference was charted in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where an outright show of large-scale resistance through marching would have been more contentious. According to the United States 1970 Census, 91 percent of Pennsylvania’s population was White, and 8.6 percent was Black. In contrast, in Mississippi, the Black-White gap was considerably smaller. In 1970, Mississippi’s white population stood at 62 percent, and its Black population stood at 36 percent.[xlvi] It is inferable that the years prior to 1970 had similar racial demographics. Outside of regional urban Black centers in the North like Chicago or Detroit, it is plausible that outside of those spaces, resistance through demonstrations needed to look different. Perhaps where racism and blatant bigotry was the loudest and affected a significant percentage of the population, the protest movement had to be just as visible, loud, and unignorable. For instance, when former Georgia representative and civil rights activist Andrew Young was asked by his interviewer about the likelihood of Black politicians getting elected in a Northern city like Detroit, Michigan, he implied that it would not occur. He stated it was unlikely because “white people up there haven’t realized they are racists,” and because they had not actively confronted it, different tactics were necessary. Young claims while the “South was separated legally,”, Black and white Southerners had lives that connected in some way or another. Whereas in the North, this “geographic separation” and cultural separation sheltered white Americans from their prejudice, thus allowing southerners to “get a long jump ahead of Northerners” in dealing with race.[xlvii] Likewise, when Martin Luther King Jr visited Chicago in 1966, he shocked many with his statement, when he called Chicago a “closed society.” [xlviii] King also stated that he had “never seen, even in Mississippi and Alabama, mobs as hateful as I’ve seen in Chicago”, thus removing the myth of northern white anti-racism and conveying the true hatred of many.[xlix] For Northern clergy and laymen, protesting injustice (on a large scale) in a society that denied its racism would have undoubtedly been more difficult than in one that was unabashed about sharing the same sentiments. Consequently, small-scale resistance by liturgical churches and their clergy should be seen as an act that was just as brave as the more famously recorded marches and arrests. Small-scale resistance, while subtle, should not be seen as inferior to large-scale resistance, as it requires actors to manipulate certain societal norms and systems deftly and inconspicuously, all while aiming to achieve something quite radical.

According to political scientist Daniel Q. Gillion, the visibility of a protest campaign is dependent on the ‘number of key characteristics’ it has. Key characteristics might include the size of the movement, violence, strong organizational support, arrest, and police presence. The more key characteristics that a protest involves, especially highly controversial ones, like police presence, violence, or arrests, the more salient the protest and its message becomes.[l] So, naturally acts of small-scale resistance, which often lack highly visible key characteristics like the police, violence, arrests, and more, have not become immortalized due to this inability to be highly detectable to the wider public. To a certain degree, the success of large-scale resistance can also be attributed to their perception. The mobilization of religious groups during the civil rights movement was viewed as more ‘neutral’ and ‘untouchable’ than secular groups. For instance, in Alabama in 1965 the attorney general obtained a court order banning the vast majority of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People’s (NAACP) activities in Alabama because of its “supporting and financing an ‘illegal boycott’ in Montgomery.” [li] A ‘political’ organization like the NAACP or Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) could and often did get banned or have its leaders targeted for having ‘communist’ ties whereas outright banning a religion or group of religious figures while their demonization occurred was more contentious. While a singular figure like Aaron Henry or Martin Luther King Jr could be labeled a communist it was difficult to use the same slander against an entire demographic like Black Christians, when the vast majority of the country identified in some way or another with Christianity.[lii] Activist Lawrence Guyot echoed this sentiment of clergy officials being a more controversial arrest or target for violence when he stated, “We expected people to be arrested. Well, the State of Mississippi we can't be arresting all of these religious people” and described a change in strategy that occurred after recognizing the state’s reluctance to arrest religious officials as “mental jujitsu.” [liii] Mental jujitsu is a term that could also describe the efforts to circumvent the civil rights movement, intact bussing in Milwaukee serves as a great case study.

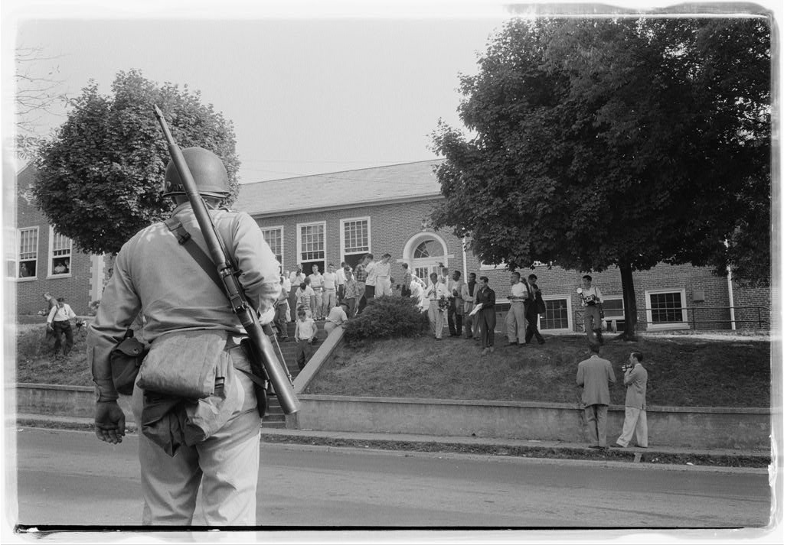

Library of Congress’ Caption: Photograph shows an armed member of the National Guard observing Clinton High School as students stand on its steps and lawn. [liv]

In Patrick D Jones’ The Selma of The North: Civil Rights Insurgency in Milwaukee, he emphasized the subtlety of northern white segregationists by using ‘intact bussing’ as an example. According to Jones, ‘intact bussing’ was “a practice whereby African American children were transported by bus to ‘white’ schools, where they were separated from the classes and students at the receiving school.” [lv] Similarly, Jones states that “White Milwaukee civic leaders “focused on the tactics rather than the issues,” meaning that many saw boycotts as problems affronting society, so much so that many tried to claim “that boycotts were illegal”.[lvi] Andrew Young partially blames the slow progress of the North on the lack of proper black leadership in the region, in contrast to the south having “generations of Ivan Allens and Martin Luther Kings.” Young stated, “You don’t have stable leadership patterns in the North. There’s a table leadership structure in the South that moves things very rapidly once people make up their minds. You don’t have three generations of black leadership in any northern city”.[lvii] While Young’s comment about the North lacking stable leadership may have been true, he aggrandizes the national and regional importance of the Kings and Allens as their prominence was significant, yet (initially) limited locally.[lviii] Additionally, greater criticism should be placed on Northern efforts to remain blameless while continually perpetuating racist policies and culture.

Small-Scale Resistance’ Long-Term Resilience

As mentioned previously, political scientist Daniel Gillion’s theory on protest saliency requires highly visible protest campaigns to have highly volatile or publicized characteristics in order to make the struggle one that the common person is aware of and can identify with. The brilliance behind the large-scale resistance and direct-action campaigns of the Civil Rights era was the organizer’s forethought on the power of the media and gaining public support through media. “If it hadn’t been for the press, the Civil Rights movement, the whole struggle would have been like a bird without wings”, claimed John Lewis, US representative, and SNCC chairman, in a 2019 Rolling Stones interview. [lix] Unfortunately, it seems that when looking at the current landscape and the one of tomorrow, the loudest and most visible efforts that were made to secure rights are the first to be attacked or revoked. Whereas the more ‘subtle’ forces of small-scale resistance seem to be more resilient or less controversial over time.

More specifically, when looking at two issues: voter disenfranchisement and segregated public schools, it appears that modern-day America has not changed much from that of the late 20th century. By and large, both voting rights and segregation were protested through forms of large-scale resistance, and their highly salient nature allowed for steps towards justice to be taken in the late 20th century. In contrast, advancements made by the Second Vatican, ESCRU, and Black Theology have largely persisted and not been overly politicized in every national election, unlike that of voting and schools.

The Civil Rights Project has published a list of states where Black and Latino (BIPOC) students have been segregated. This list found New York, Illinois, Michigan, and New Jersey are consistently at the top of the list for being the most segregated. Significantly the study states that of the 17 southern states that were legally mandated to desegregate schools none of the southern states “have headed this list since l970—in spite of the fact that twelve of them have higher shares of black students than the most segregated states today”.[lx] In this case, modern-day trends are likely reflective of past Supreme Court decisions for Milliken v. Bradly (1974), where it was essentially ruled that benign de-facto segregation had occurred in Detroit. The decision concluded that school district lines had been drawn without malice and without any racist intent, thus negating the need for redistricting. Miliken v. Bradley is noteworthy as it prevented suburban participation in desegregation and thus caused high levels of segregation in modern-day schools. However, the case is also one of the first examples of a successful regression of the progress made during the civil rights movement. Similarly, voter disenfranchisement is at an all-time high. Gerrymandering, the manipulation of an electoral constituency to favor a particular party, tends to hurt minority voters the most. Nicholas Stephanopoulos, a professor at the University of Chicago Law School, stated that Republicans “[have] been arguably using the racial demographics as a way to enact a gerrymander” through their redistricting efforts.[lxi] Therefore, partially rendering the efforts of the Civil Rights to increase Black political power null and void.

Looking ahead, greater attention to national narratives and rhetoric is needed so that a critical eye will turn to all corners of the country and every representative’s choice to defend or attack all American’s civil liberties. Greater attention might come because of a better understanding of the nation’s history. In popular media and history, most Americans associate the North with freedom and the South with slavery. For many, this strict dichotomy of the immoral South and benevolent North applies not only to the Antebellum period but also to the Jim Crow Era and beyond. While this binary line of thought has elements of truth, it is by far an oversimplification of reality. This oversimplification often occurs when the North’s complacency or active participation in one of the Nation’s greatest sins gets ignored. Historians Nicholas Cords and Patrick Gerster discern that southern mythology has Northern origins and careful examination of “the role the Yankee has played in both the original creation and the tenacious upholding of the South’s legendary past” is needed for progress and critical analysis.[lxii] Here the South is a scapegoat for national issues or one large cancerous tumor that the rest of the country must remove in order to move on from the past and forget its sins. [lxiii] This collective memory of the past fails to adequately address the different ways in which Black Americans were terrorized or institutionally disenfranchised in the North. Similarly, popular memory has also distorted the efficacy of the Church and differences among Black Christian denominations in the 1960s. The root evil of this ‘forgotten’ memory is that the stories they tell lack nuance and tell a single story. Additionally, it also tends to devalue small-scale/local-community-based resistance, which is a form of resistance that is more readily accessible, safe, and less stigmatized; but its depreciation can leave people voiceless.

Therefore, when remembering the past, small-scale resistance should be celebrated as it is a form of protest that is just as valuable. Additionally, it might even predate large-scale protests in many instances. Consequently, by elevating small-scale resistance and seeing it as a legitimate form of resistance, the role of liturgical churches during the Civil Rights movements became even more important and inspirational.

Bibliography

Alexander, Margret Walker. Aaron Henry: The Fire Ever Burning. Oxford: University Press of Mississippi, 2000.

Belfrage, Sally. Freedom Summer. Charlottesville, The University Press of Virginia, 1990.

Breton, William L., Circa Artist. Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania,1829. Philadelphia: Kennedy & Lucas's Lithography, -07. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2021670179/

Bishop Howse, Joseph. Interview with Larry Crowe, November 12, 2002. The History Makers Digital Archive, Session 1, tape 2, story 6.

Camp, Stephanie. Closer to Freedom: Enslaved Women and Everyday Resistance in the Plantation South. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2004.

Cornell Law Legal Information Institute, Protest. https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/protest

Cressler, Matthew J. “Black Power, Vatican II, and the Emergence of Black Catholic Liturgies.” U.S. Catholic Historian, vol. 32, no. 4 (2014), 103. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24584696

Critchlow, Donald T. In Defense of Populism: Protest and American Democracy. College Station, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020.

Days, Michael, Black Catholics deserved recognition in PBS doc on Black churches | Opinion, The Philadelphia Inquirer, February 25th 2021. https://www.inquirer.com/opinion/commentary/black-churches-pbs-catholics-20210225.html

Delano, Jack, photographer. Mass at a Negro Catholic church on the South Side. Chicago, Illinois. Cook County Illinois Chicago, 1942. Mar. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2017828698/.

Delano, Jack, photographer. Church service in the Negro church. Greene County, Georgia, 1941. Oct. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2017796561/.

Du Bois, W. E. B. Collector. Sisters of the Holy Family. New Orleans, Louisiana, 1899. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2001705864/.

Family History of Martin Luther King Jr., Martin Luther King Encyclopedia, Stanford: The Martin Luther King Jr. Research and Education Institute. https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/encyclopedia/family-history-martin-luther-king-jr

Genovese, Eugene D. Roll Jordan, Roll. New York: Vintage, 1974.

Gerster, Patrick and Cords, Nicholas. "The Northern Origins of Southern Mythology," Journal of Southern History 43 (November 1977): 567–82. https://doi.org/10.2307/2207006.

Gillion, Daniel Q. The Loud Minority. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2010.

Highsmith, Carol M, photographer. Renovated Greyhound Bus Station. Jackson, Mississippi, 2017. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2017883563/.

Hoskins, Charles Lwanga. Black Episcopalians In Georgia: Strife, Struggle, and Salvation. Savannah, Georgia: St. Matthew’s Episcopal Church, 1980.

Jones, Jeffery M. “How Religious Are Americans?,” Gallop News, December 23rd 2021. https://news.gallup.com/poll/358364/religious-americans.aspx

Jones, Patrick D. The Selma of The North Civil Rights: Insurgency in Milwaukee. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2010.

Lawrence Guyot (The HistoryMakers A2004.228), interviewed by Racine Tucker Hamilton, November 9, 2004. The HistoryMakers Digital Archive. Session 1, tape 3, story 5.

Leffler, Warren K., photographer. African American demonstrators outside the White House, with signs. Selma, Alabama, 1965. Photograph. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.print

Marx, Gary T. Negro Political Attitudes. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research, 1964.

Murray, Pauli and Rosalind Rosenberg. Jane Crow: The Life of Pauli Murray. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017.

O'Halloran, Thomas J, photographer. Clinton, TN School Integration Conflicts. Tennessee Clinton, 1956. Sept. 1. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2003654352/.

Pearce, Matt. “When Martin Luther King Jr. took his fight into the North and saw a new level of hatred,” The LA Times January 18th, 2016. https://www.latimes.com/nation/la-na-mlk-chicago-20160118-story.html

Pratt, Waldo Selden. “The Liturgical Responsibilities of Non-Liturgical Churches.” The American Journal of Theology 5, no. 4 (1901): 641-2. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/pdf/10.1086/477856

Young, Andrew, with Jack Bass. January 31, 1974. Interview A-0080. Southern Oral History Program Collection (#4007) Wilson Library, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Randall Herbert. Interview by Adrienne Jones. The History Makers A2007.276, September 28, 2007. The History Makers Digital Archive, Session 1, tape 5, story 5.

Reverend Dr. Handy, Maisha. Interview by Larry Crowe, August 22, 2005. The History Makers Digital Archive A2005.200, Session 1, tape 4, story 2.

Reverend Murray, Cecil L, Interview by Paul Brock, October 3, 2005. The History Makers Digital Archive A2005.225, Session 1, tape 4, story 6.

Rothschild, Mary Aickin. “The Volunteers and the Freedom Schools: Education for Social Change in Mississippi.” History of Education Quarterly, vol. 22, no. 4 (1982): 401–20. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/368066.

Sister Ralph Patricia. Interview by Racine Tucker, May 17, 2004. The History Makers Digital Archive A2004.049, Session 1, tape 2, store 11.

Smith, Jamil. “Civil Rights Icon John Lewis on the Art of Making ‘Good Trouble.’” Rolling Stone, May 3rd, 2019. https://www.rollingstone.com/politics/politics-features/john-lewis-congressman-civil-rights-donald-trump-825629/

Soffen, Kim. “How racial gerrymandering deprives black people of political power.” June 9th 2016, The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2016/06/09/how-a-widespread-practice-to-politically-empower-african-americans-might-actually-harm-them/

Townsend, Craig D. Faith In Their Own Color. New York City: Columbia University Press, 2023.

U.S. Census Bureau 1970. US Department of Commerce/Bureau of the Census.

Orfeild, Gary, Jongyeon Ee, Erica Frankeberg, and Genevieve Sigel-Hawley Genevieve. “Brown at 62: School Segregation By Race, Poverty and State.” Civil Rights Project, UCLA May 16, 2016. https://www.civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/research/k-12-education/integration-and-diversity/brown-at-62-school-segregation-by-race-poverty-and-state/Brown-at-62-final-corrected-2.pdf

Footnotes

[i] Leffler, Warren K., photographer. African American demonstrators outside the White House, with signs "We demand the right to vote, everywhere" and signs protesting police brutality against civil rights demonstrators in Selma, Alabama 1965 March. Photograph. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.print

[ii]Marx, Gary T. Negro Political Attitudes, 1964. ICPSR07002-v1. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], 2007-12-19. http://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR07002.v1

The surveyed sample draws respondents from Chicago, New York, Atlanta, and Birmingham, and since the specific demographics are not specified for each response, this survey is eye-opening yet unreliable and was not used beyond this introduction.

[iii] Ibid

[iv] Pratt Waldo Selden, The Liturgical Responsibilities of Non-Liturgical Churches, 641-642. 1901 The American Journal of Theology Volume V Number 4.https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/pdf/10.1086/477856

[v] Breton, William L., Circa Artist. Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church, Philadelphia. Pennsylvania United States of America Philadelphia, 1829. Philadelphia: Kennedy & Lucas's Lithography, -07. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2021670179/

[vi] Bethel Church was founded in the 1790s by free Blacks who, thanks to racial discrimination, broke away from Saint George’s Methodist Episcopalian Church.

[vii]In this essay, the Black Church is defined as a church whose congregation and clergy is majority Black.

[viii] Sister M. Martin de Porres Grey, “The Church, Revolution And Black Catholics”, The Black Scholar, pg 25; Pratt Waldo Selden, The Liturgical Responsibilities of Non-Liturgical Churches, 641-642. 1901 The American Journal of Theology Volume V Number 4.https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/pdf/10.1086/477856

[ix] Days Michael, Black Catholics deserved recognition in PBS doc on Black churches | Opinion, The Philadelphia Inquirer, February 25th 2021. https://www.inquirer.com/opinion/commentary/black-churches-pbs-catholics-20210225.html

[x] Cornell Law Legal Information Institute, Protest. https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/protest

[xi] Delano, Jack, photographer. Woodville, Greene County, Georgia. Church service in the Negro church. United States Greene County Georgia Woodville, 1941. Oct. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2017796561/

[xii]Eugene D, Genovese, Roll Jordan, Roll.

[xiii] Stephanie Camp, Closer to Freedom: Enslaved Women and Everyday Resistance in the Plantation South, 42.

[xiv] Stephanie Camp, Closer to Freedom: Enslaved Women and Everyday Resistance in the Plantation South, 62.

[xv]Pauli Murray and Rosalind Rosenberg, Jane Crow: The Life of Pauli Murray, 149.

[xvi] Eugene D. Genovese, Roll Jordan, Roll.

[xvii]Craig D. Townsend, Faith In Their Own Color, 118.

[xviii]It is also worth noting that by 1804 all Northern states abolished slavery, a full 59 years before the Emancipation Proclamation and roughly 61 years before many of the enslaved were physically freed by Union forces and aware of said freedom.

[xix]Townsend D Craig, Faith In Their Own Color, 3.

[xx] Ibid.

[xxi] Townsend D Craig, Faith In Their Own Color, 2-3.

[xxii]Hoskins, Charles Lwanga, Black Episcopalians In Georgia: Strife, Struggle, and Salvation,1980 St. Matthew’s Episcopal Church, 83-85.

[xxiii]Hoskins, Charles Lwanga, Black Episcopalians In Georgia: Strife, Struggle, and Salvation,1980 St. Matthew’s Episcopal Church, 5, 22, 35.

[xxiv] Highsmith, Carol M, photographer. The renovated Greyhound bus station in downtown Jackson was the site ofFreedom Rides, where activists protested segregated bus stations. It now 2017 contains an architect's office. United States Mississippi Jackson Jackson County, 2017. -11-05. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2017883563/.

[xxv]Hudson Winson, Mississippi Harmony, 3.

[xxvi]In Mississippi, Freedom Summer and the various other projects that were related (IE: Freedom Schools, Freedom Rides, etc.) were created by SNCC and then facilitated by “an umbrella organization called the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO)”; Rothschild, Mary Aickin. “The Volunteers and the Freedom Schools: Education for Social Change in Mississippi.” History of Education Quarterly, vol. 22, no. 4, 1982, pp. 401–20. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/368066.

[xxvii]Guyot, Interview.

The National Council of Churches is a diverse covenant community of 37 member communions and over 30 million individuals –100,000 congregations from Protestant, Anglican, historic African American, Orthodox, Evangelical, and Living Peace traditions.

[xxviii]Guyot, Interview.

[xxix]The official Archives of the Episcopal Church state that “In December 1959, approximately one hundred lay and ordained Episcopalians organized ESCRU in an attempt to remove all vestiges of segregation from the life of the Church. The group took issue with the de facto racial segregation that dominated much of Church life in the South”. The ESCRU adopted various popular forms of direct action protest to public segregation and racial exclusion in the church.

[xxx]Breeden, Interview.

[xxxi] Morris, Interview; “The Episcopal Society for Cultural and Racial Unity: Statement of Purpose”, [1960].

[xxxii] “Study Sees Episcopalian Lacking Social Education,” ECU 120 (Oct. 5, 1952; 4).

[xxxiii]Hudson Winson, Mississippi Harmony, 76; Sally Belfrage, Freedom Summer, The University Press of Virginia, 90.

[xxxiv]Randall, Interview.

[xxxv]Ladner, Interview; Belfrage Sally, Freedom Summer, 90.

[xxxvi]Townsend, Faith In Their Own Color, 5.

[xxxvii]Delano, Jack, photographer. Mass at a Negro Catholic church on the South Side. Chicago, Illinois. United States Cook County Illinois Chicago, 1942. Mar. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2017828698/

[xxxviii]Reverend Murray, Interview.

[xxxix]Reverend Handy, Interview.

[xl]Matthew J. Cressler, “Black Power, Vatican II, and the Emergence of Black Catholic Liturgies,” U.S. Catholic Historian 32, no. 4 (2014): 99. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24584696

[xli]Matthew J. Cressler, “Black Power, Vatican II, and the Emergence of Black Catholic Liturgies,” U.S. Catholic Historian 32, no. 4 (2014): 103. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24584696.

[xlii]Bishop Howze, Interview.

[xliii]Sister Ralph, Interview.

[xliv]Ibid

[xlv] W. E. B. Du Bois, Collector. Sisters of the Holy Family, New Orleans, La. New Orleans Louisiana, 1899. [?] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2001705864/

[xlvi]U.S. Census Bureau 1970.US Department of Commerce/Bureau of the Census, PC VC-1 (Advanced Report). 5,9.

[xlvii]Young, Interview

[xlviii]Matt Pearce, “When Martin Luther King Jr. took his fight into the North, and saw a new level of hatred”, The LA Times January 18th 2016. https://www.latimes.com/nation/la-na-mlk-chicago-20160118-story.html It is also worth noting that according to the US 1970 Census the state of Illinois had a population that was 86% white and 12.8% Black, thus showing a similar trend of marginalized Black Americans experiencing a disadvantage as a result of the size of their community and the surrounding ones.

[xlix]Matt, Pearce, “When Martin Luther King Jr. took his fight into the North, and saw a new level of hatred”, The LA Times January 18th 2016. https://www.latimes.com/nation/la-na-mlk-chicago-20160118-story.html

[l]Daniel Q Gillion, The Loud Minority, 43.

[li]Donald T. Critchlow, In Defense of Populism: Protest and American Democracy, 78.

[lii]Jeffery M. Jones, “How Religious Are Americans?,” Gallup News, December 23rd 2021. https://news.gallup.com/poll/358364/religious-americans.aspx; Alexander Margret Walker, Aaron Henry: The Fire Ever Burning.

[liii]Guyot, Interview.

[liv] Thomas J. O’Halloran, photographer. Clinton, TN. “School integration conflicts.” Tennessee Clinton, 1956. Sept. 1. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2003654352/

[lv]Patrick D. Jones, The Selma of The North Civil Rights: Insurgency in Milwaukee, 65.

[lvi]Patrick D. Jones, The Selma of The North Civil Rights: Insurgency in Milwaukee, 70.

[lvii] Young, Interview

[lviii]Family History of Martin Luther King Jr., Martin Luther King Encyclopedia, Stanford: The Martin Luther King Jr. Research and Education Institute. https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/encyclopedia/family-history-martin-luther-king-jr

[lix]Jamil Smith, Civil Rights Icon John Lewis on the Art of Making ‘Good Trouble’, Rolling Stone, May 3rd 2019. https://www.rollingstone.com/politics/politics-features/john-lewis-congressman-civil-rights-donald-trump-825629/

[lx]Orfeild Gary, Ee Jongyeon, Frankeberg Erica, Sigel-Hawley Genevieve, Brown at 62: School Segregation By Race, Poverty, and State, Civil Rights Project/UCLA. May 16, 2016. https://www.civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/research/k-12-education/integration-and-diversity/brown-at-62-school-segregation-by-race-poverty-and-state/Brown-at-62-final-corrected-2.pdf

[lxi]Soffen Kim, How racial gerrymandering deprives black people of political power, June 9th 2016, Washington Post .https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2016/06/09/how-a-widespread-practice-to-politically-empower-african-americans-might-actually-harm-them/

[lxii]Gerster, Patrick and Cords, Nicholas, "The Northern Origins of Southern Mythology," Journal of Southern History, 43 (1977): 567. https://doi.org/10.2307/2207006

[lxiii]Patrick Gerster and Nicholas Cords, "The Northern Origins of Southern Mythology," Journal of Southern History, 43 (1977): 575. https://doi.org/10.2307/2207006

Hannah Davies

Hannah Davies is a senior at Denison University, scheduled to graduate in May 2024, with a double major in History and Global Commerce. She conducted this research and wrote this paper when she was selected to be a Denison University independent research summer scholar.

When it comes to historical research and exploration, she greatly enjoys learning about American History, including the following eras: Colonial, Antebellum, Reconstruction, and Civil Rights. In addition, she has also greatly enjoyed learning and researching East Asian history, more specifically, Medieval East Asian history, Modern Chinese history (post-1880), and Modern East Asian history (post-1880).