Dirck Jacobsz's Artistic Family Lineage and Identity In "Jacob Cornelisz Painting His Wife Anna"

By Melody Hsu

Dirck Jacobsz, Jacob Cornelisz. van Oostsanen Painting a Portrait of His Wife, about 1550, Oil on wood panel, 24 7/16 x 19 7/16 in. (Toledo Museum of Art, Toledo, OH). Purchased with funds from the Libbey Endowment, Gift of Edward Drummond Libbey.

Introduction

Between October 1, 2021 and January 16, 2022, the Rijksmuseum of Amsterdam presented an exhibition titled Remember Me that brought together more than a hundred portraits painted by well-known great masters to lesser-recognized artists of the fifteenth and sixteenth-century Italian, Northern-European, and Flemish Renaissance. What is portraiture? Beyond the vivid depiction of a person’s likeness, portraiture entails the complex histories, identities, social status, desires, memories, and ambitions hidden behind the carefully crafted visual representation of the sitter. Art historian Sir John Wyndham Pope-Hennessy stated, “Portraiture, like other forms of art, is an expression of conviction, and in the Renaissance, it reflects the reawakening interest in human motives and the human character, the resurgent recognition of those factors which make human being individual, that lay at the center of Renaissance life.”1 Portraiture could evoke a fictive or an actual narrative of one’s love, loss, aspiration, character, lineage, and life that are immortalized by the artists’ mastery of portrait production.2

One of the highlights of the Remember Me exhibition is the early sixteenth-century Dutch painter Dirck Jacobsz’s (1497–1567) Jacob Cornelisz painting his wife Anna (around 1550), also known as Jacob Cornelisz. van Oostsanen Painting a Portrait of His Wife (Fig.1). The portrait was formerly dated to around 1530 and was believed to be a self-portrait of Dirck’s father Jacob Cornelisz (1470 –1533), who owned an important workshop as a painter and woodcut printmaker in late fifteenth and sixteenth-century Amsterdam. Today, with a more evolved technical analysis, Jacob Cornelisz painting his wife Anna is now dated to around the 1550s and it is attributed to Jacob’s son Dirck Jacobsz.3 The Rijksmuseum labels Dirck’s painting with the following description:

Originally, this picture showed his father working on a self-portrait. Technical analysis has revealed that underneath the head of the woman is an incomplete self-portrait of Jacob. Apparently, Dirck changed his mind, because we now see his painting not as a self-portrait, but as one of his wife Anna, Dirck’s mother. The result is effectively a family portrait – of the deceased father, the mother, and the invisible but implicitly present son. Most likely, it was therefore meant for family viewing in a private setting.4

The Rijksmuseum identifies Dirck’s Jacob Cornelisz painting his wife Anna as a commemorative family portrait, which has been the most common interpretation of Dirck’s painting in recent scholarships of the past two decades. In fact, the Renaissance experienced increasing social and cultural practices to commemorate family identity and lineage through various means, including the commemoration of the dead through art production such as portraiture and bust sculpture. Expressing family memory through sculpted busts and painted portraits can both evoke a similar duality of meaning, “either they are self-conscious expression by members of the ruling class who want to set a model for their followers in the family, or they are the memorial homage to illustrious forebears, made by their sons.”5

It is adequate to consider Dirck’s Jacob Cornelisz painting his wife Anna as a commemorative family portrait based on visual analysis and existing biographical documentation. The painting is now dated to around 1550, painted around the same time of Dirck’s mother Anna’s death and almost twenty years after Dirck’s father Jacob Cornelisz’s death. The gap between Dirck’s parents’ deaths can be visually observed. In Dirck’s painting, Jacob’s skin looks much more youthful than Anna’s, who appears as her actual old age when Dirck painted this double portrait, around the same time of her death. Dirck’s father appears at his age shortly prior to his own death in 1533, an appearance that was immortalized and remembered through Jacob’s own Self-Portrait painted right before his death (Fig. 2). Given the straightforward visual similarities between Jacob’s Self-Portrait and Dirck’s depiction of his father in Jacob Cornelisz painting his wife Anna (Fig. 3), Dirck might have used his father’s self-portrait as a reference to capture his father’s likeness for his painting. Based on existing findings about Dirck’s painting, it is not possible to determine whether the painting was painted during Anna’s living years. It was probably painted close to her death; yet, it is clear that the portrait serves a commemorative purpose in memories of Dirck’s deceased parents.

Detail of Anna. Dirck Jacobsz, Jacob Cornelisz. van Oostsanen Painting a Portrait of His Wife, about 1550, Oil on wood panel, 24 7/16 x 19 7/16 in. (Toledo Museum of Art, Toledo, OH).

Art historians have established that Dirck’s Jacob Cornelisz painting his wife Anna is a family memorial portrait of his deceased father and, probably, of his recently deceased mother. The double-portrait was possibly installed above his parents’ grave. As Ann Jensen Adams noted, “it has been plausibly suggested that the portrait was located at the time in a church, as a memorial to Jacobsz’s mother Anna.”6 Gazing directly at the viewer while holding firmly his painter’s palette and brushes, Dirck’s father Jacob Cornelisz sits confidently in front of his panel painting of his wife Anna placed on his wooden easel. Both Dirck’s parents gaze strongly at their viewers, leading us to ask, who were the originally intended viewers of Jacob Cornelisz painting his wife Anna? As the Rijksmuseum suggested, the painting is a family commemorative portrait and was plausibly meant for private viewing which includes intended viewers such as Dirck, Dirck’s mother (if the painting was painted before her death), and other members of Anna’s and Jacob’s lineage. Most arguably, Dirck could be identified as the original intended viewer of this double portrait painted in memories of his deceased parents. Dirck positioned himself both as the painter and the viewer, becoming the subject of his parents’ gazes; while vice-versa, his parents became the subject of Dirck’s gaze. Hence, Dirck’s family memorial portrait entails a double-sided viewership that evokes one family’s memories.

Currently, there is little scholarly research on Dirck’s Jacob Cornelisz painting his wife Anna, nor on his life and works. According to archival databases such as the biographical reference works Nieuw Nederlandsch Biografisch Woordenboek, it is known that Dirck came from an artistic family. Dirck likely received his initial artistic training from his father.7 However, most archival documentation and works of Dirck, his father Jacob, and other artist members of his family are now lost and limited. Hence, Dirck’s works and his family's artistic identity require new research. Rather than studying Dirck’s painting solely as a commemorative family portrait, I am interested in examining Dirck’s personal artistic intention when he painted this double portrait of his deceased parents. What are Dirck and his artistic choices trying to convey? Therefore, my research investigates the visual construction of Dirck Jacobsz’s artistic family identity – his artistic identity as a son of a portrait painter – in Jacob Cornelisz painting his wife Anna through an art historical and iconographical lens.

My research aims to identify Jacob Cornelisz painting his wife Anna as Dirck Jacobsz’s artistic statement about his identity as a portrait painter and as a son of a portrait painter who successfully mastered and inherited his father’s portrait painting skills and techniques. My investigation of Dirck Jacobsz’s artistic identity begins with a biographical and art historical exploration of his father Jacob Cornelisz’s artist workshop in Kalverstraat, Amsterdam. The first part of my research examines Dirck’s artistic family’s lineage, including a discussion of the practice of artists working as a family dynasty across generations during the late fifteenth and throughout the seventeenth-century patriarchal Dutch art scene. As the male descendant of an artistic family, Dirck Jacobsz would naturally inherit his father’s artistic identity as a portrait painter. The second part of my paper visually analyzes the formal and iconographical features portrayed in Jacob Cornelisz Painting His Wife Anna; what do the setting and the painter’s objects try to convey? I suggest the possibility to interpret the painting as a commemorative family portrait that celebrates the artistic identity and honors the mastery of portrait paintings and studio practices between two male generations of an artistic family.

Artistic Family Lineage: The Inheritance of Artistic Identity Across Generations

Genealogy of Jacob Cornelisz’s lineage according to Yvonne Bleyerveld’s biographical research (Sound & Vision Publishers 2019).

Currently, biographical documentation and surviving works of Dirck Jacobsz and his father Jacob Cornelisz are sparse. Yet, the Het Schilder-Boeck (The Book of Painters), written by the Netherlandish art historian and painter Karel Van Mander in 1604, mentions briefly Dirck’s father Jacob Cornelisz’ life, family, and work. In Schilder-Boeck, Van Mander described Dirck’s father Jacob Cornelisz as “the fame-worthy, celebrated painter Jacob Cornelisz of Oostsanen in Waterland […] it is not known who trained Jacob… [As Van Mander wrote,] he arrived at art, even though he was born and bred among peasants […] he was experienced in art and had children already growing up.”8 Therefore, it is possible to understand that Jacob Cornelisz might not come from an artistic family; rather, he was plausibly a self-made artist who learned his craft from the Amsterdam Master of the Figdor Deposition, or perhaps, from other painters such as Geertgen tot Sint Jans.9 Hence, his son Dirck Jacobsz might be the first generation who carried on their artistic family identity that was created, founded, and established by Jacob Cornelisz himself. As a young man in his early twenties, Jacob ran a productive artist studio with his own assistants and students. His independent workshop was strategically located in Kalverstraat, which was “the center of the economic, religious, and cultural heart of Amsterdam.”10 Based on biographical research compiled by Yvonne Bleyerveld from the University of Leiden, it is possible to identify him as a well-established woodcut producer, printmaker, and painter in the early first decades of the sixteenth-century Dutch art scene. During the Flemish Renaissance and throughout the seventeenth-century Dutch Republic, a man’s social identity and status were determined principally by his occupation that was generally inherited from his family. Within an artistic family’s workshop, the male descendants would naturally learn their father’s artistic craft, proceed to master their father’s artistic skills and techniques, and eventually transmit the artistic practices to their sons. This creates an artistic family identity from one generation to the next, forming the phenomenon of an artistic family dynasty. This practice ensured the continuity of the family profession, reputation, and status as skilled and legitimate artisans. For instance, as Margaret Haines explains, “Consolidation of professional activity over more than one generation permitted the development of a shop reputation and the elaboration of family strategies of advancement. If widows and heirs extraneous to the artist’s shop found themselves saddles with partly paid, unfinished works and were bound to suffer losses, a shop’s passage from father to son could take place almost imperceptibly.”11

Consequently, if Jacob Cornelisz was not born into an artistic family, it is impressive that he might be a successful self-made artist who established, on his own, an artistic family dynasty — an artistic profession that his sons successfully continued. Based on Jacob Cornelisz’s genealogy studied by Bleyerveld (Fig. 4), his children all managed to preserve their family’s artistic identity according to the standard social norms and practices of their times. Jacob, with his wife Anna, had two sons and two daughters. The two male descendants, Cornelis and Dirck, both became successful painters. As the older son of the family, Dirck’s brother Cornelis eventually inherited his father’s workshop in Kalverstraat. Dirck, on the other hand, probably established a workshop of his own. According to the Nieuw Nederlandsch Biografisch Woordenboek, after a few years of initial training at his father’s workshop, Dirck continued his artistic apprenticeship at the guild, possibly at the renowned painter’s guild in Haarlem, as a master painter. Dirck eventually married Marie Gerrits with whom he had two children, a daughter named Marie, and a son named Jacob Dirks Werre, who also became a painter.12

On the same note, Jacob’s two daughters also contributed to the continuity and stability of their family’s artistic lineage through marriage ties; indeed, daughters’ marriages were an important tactic in achieving successive familial generations.13 As Jensen Adams states, “the identity of each family member [was] defined through their membership in that lineage, both through their relationship with their own ancestors and sometimes also with those of their spouses.”14 Jacob’s youngest daughter, Anna, married Michiel Burgman who was an Amsterdam goldsmith and assay-master.15 His eldest daughter, whose name is unknown, married Jacob’s assistant Thonis Egbertsz, and their son Cornelis Anthonisz was trained to become a painter, printmaker, and cartographer at the Kalverstraat workshop.16 As the son of a father who owned a renowned workshop located right at the artistic and cultural hub of Amsterdam, Dirck successfully became a male descendant who gave prominence to his family’s artistic identity and lineage. He mastered the painter’s craft first learned from his father, established his own workshop, and gave birth to a son who also became a painter. Dirck was destined to be an artist by birth, and he transmitted his family’s artistic identity from one generation to the next, thus establishing a continuity of the artistic family dynasty.

Dirck’s Artistic Statement in Jacob Cornelisz painting his wife Anna

Gazing directly at us while holding firmly his painter’s palette and brushes with his large artist hands, Dirck Jacobsz’s father Jacob Cornelisz. van Oostsanen (1470–1533) sits confidently in front of his almost-finished portrait of his wife Anna – Jacobsz’s mother – painted on a panel that is placed on a wooden easel. Jacobsz’s portrayal of his painter's father at work is considered today as the earliest known portrait of a painter at his easel. Like other artist families in the Renaissance, Jacobsz learned the fine craft of portrait painting from his father Jacob Cornelisz. van Oostsanen, who was one of the most important artists who worked in early 16th century Amsterdam as a portrait painter and woodcuts designer. Despite being known today mostly for his woodcuts prints (since most of his paintings have been lost or greatly damaged), it is possible to argue that Jacob must have identified himself primarily as a painter rather than as a printmaker or woodcut designer when he held his prosperous workshop in Kalveerstraat. The professional craft of painting was regarded as more prestigious than printmaking in the social context of his time. As Bleyerveld discusses in her research, “although we know little about Jacob Cornelisz’s personal life we have a book that he owned. It is a copy of the Delft Bible… It is inscribed in a typical early sixteenth-century hand: ‘Dit bouck hoert two Jacob cornelisz die schilder wonende in die calverstraet’ (‘This book belonged to Jacob Cornelisz the painter, living in Kalveerstraat’), with the date 1502 below. So in 1502, he evidently regarded painting as his main activity.”17 Dirck’s artistic identity as a portrait painter and as a son of a portrait painter who successfully mastered/inherited his father’s artistic craft can be visually comprehended through a formal and iconographical analysis of Jacob Cornelisz painting his wife Anna. As Joanna Woods-Marsden argues, “In a portrait, the relationship between painter and sitter is the crucial component informing the work of art, and all portraiture implies a silent dialogue between these two agents.”18

Dirck’s inheritance of his family’s artistic identity as one among the male offspring can be examined through the father-son relationship that is implicitly presented in Jacob Cornelisz painting his wife Anna. As Woods-Marsden explains:

Renaissance people believed that the father-son relationship was a pivotal one in society, even after the son was fully grown. Legislation determined that the two formed a ‘community, almost personal unity’, or as Marsilio Ficino put it, ‘the son is mirror and image in which the father after death almost remains alive for a long time.’ […] The son was, in theory, the father’s immortality, enabling his identity to continue. […] when the father became older, ‘he should want to become the son, and the son should take the father’s place and run everything’. 19

Jacob Cornelisz van Oostsanen, “Portrait of Jacob Cornelisz van Oostsanen,” 1533, Oil on panel, h 37.8cm × w 29.4cm. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.8170

Based on Woods-Marsden’s studies, it is possible to interpret Dirck’s portrayal of his father as a reflection of himself, thus evoking a self-portrait of Dirck that embodies a father-son relationship. Dirck’s painting is currently dated to around the 1550s. And so, Dirck was in his fifties when he painted this portrait of his father Jacob, whose likeness was plausibly portrayed by referencing his father Jacob’s Self-Portrait that was painted when he was also in his late fifties and sixties. Hence, when Dirck painted Jacob Cornelisz painting his wife Anna, Dirck was around the same age as his father when he passed away in 1533. The son and the father thus became the mirrored image of each other, evoking Dirck’s artistic legacy. Dirck was plausibly the original intended viewer of this double portrait painted in commemoration of his deceased parents. The painting evokes a double-sided viewership that entails an intimate familial relationship between the father, the mother, and the son. Yet, the father-son relationship is presented with greater prominence: Dirck’s father Jacob appears as an actual living figure; whereas his mother Anna appears as an image painted by his father. The father and the son could be understood as the primary active participants of this portrait in which the painter identity of the father and the son fuse as one, whereas the mother receives honor and veneration as the “subject” of the painting.

Dirck’s statement about his successful mastery of his father’s portrait painting skills and techniques is visually presented in his painting. Jacob Cornelisz painting his wife Anna is painted with oil on a wood panel, which is a portrait painting practice that is identically portrayed in Dirck’s painting. Jacob holds his painter’s palette filled with precise colors (flesh colors no less) of oil paint while sitting in front of his unfinished oil on panel portrait painting of his wife Anna that stands on a wooden easel. Through this scene, it is possible to read Dirck’s painting as an artistic demonstration of his successful mastery of his father's portrait painting techniques that also symbolizes the ability of painting to bring people back to life in living color. Both Jacob and Dirck plausibly mastered the craft of oil portraiture on wood panels at the local Guild of St. Luke in Haarlem, which was the most important community of artists, including painters, sculptors, and gold- and silversmiths. The oil on panel painting technique was most likely from the schilders (painters) community. Indeed, at the painter’s Guild of St. Luke, there were two painters’ communities: “schilders and cleederscrivers. The first term was applied to artists whose primary occupation was the painting of panels… Cleederscrivers, on the other hand, […] is used in the guild registers to refer to artists known to have worked on cloth.”20 Hence, it is possible to read Dirck’s painting as his method to showcase his perfect mastery and application of the artistic craft learned from his father. Dirck showcases himself as a clever modern artist who mastered the naturalism and illusionistic play across generations of traditional craft of painting.

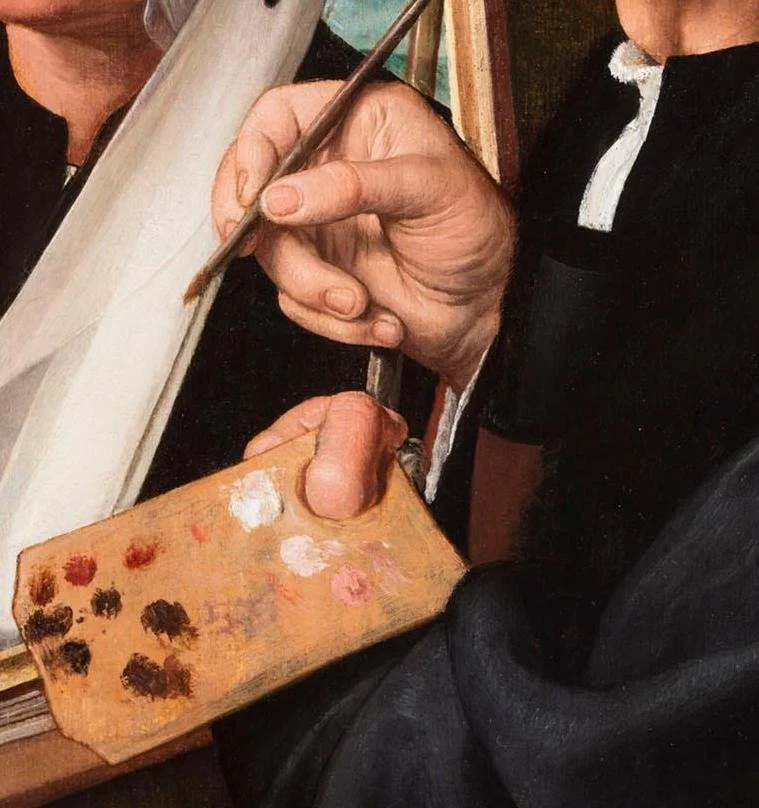

Detail of Jacob Cornelisz’s hands. Dirck Jacobsz, "Jacob Cornelisz van Oostsanen Painting a Portrait of His Wife," about 1550, Oil on wood panel, 24 7/16 x 19 7/16 in. (Toledo Museum of Art, Toledo, OH).

Dirck showcases his perfect mastery of portrait painting in Jacob Cornelisz painting his wife Anna through his distinctive portrayal of his father’s artistically trained hand. The Remember Me exhibition catalog mentions Dirck’s “strong emphasis on the profession of his deceased father; his right hand is exceptionally large, and he is holding his painter’s palette in his left hand.”21 I suggest Dirck’s careful portrayal of his father’s hands can be understood as a statement about the artistic intellect that he had fruitfully inherited as the son of a portrait painter. In fact, the Renaissance art scene stressed an important emphasis on painters’ hands. Renaissance artistic communities believed that talent in art cannot be learned, rather there was an “inborn talent or creative power needed to conceive the work in the first place.”22 As Joanna Woods-Marsden explains:

The hand was to be understood as an extension of the mind, as in Alberti’s claim that his objective in his treatise was to ‘instruct the painter how he can represent with hand [mano] what he has understood with his talent [ingegnio]… Vasari sustained that only a ‘trained hand’ could mediate the idea born in the intellect, or, as Michelangelo put it in a famous sonnet, ‘the hand that obeys the intellect’ (la man che ubbidisce all-intelletto) – in other words, the ‘learned hand’ (docta manus)....23

Thus, it follows that Dirck’s strong emphasis on his father’s hands in Jacob Cornelisz painting his wife Anna can also be interpreted as his statement about his own proud identity as a successful portrait painter possessed of intellectual, manual, and technical talent. As the Nieuw Nederlandsch Biografisch Woordenboek stated, Dirck was especially famous for painting hands. According to Van Mander’s writings, artist Jacob Raevaeart once offered a large sum of money to Dirck to have his hands painted exclusively by Dirck in a portrait.24 Therefore, Jacob’s large hands in Dirck’s painting might be Dirck’s subtle design to visually display his outstanding and well-celebrated hand painting skills.

Conclusion

Jacob Cornelisz painting his wife Anna is a fascinating surviving work of Dirck Jacobsz, whose work, life, family lineage, and identity require new research. The acknowledgment of Dirck’s artistic identity is an ongoing inquiry. Rather than interpreting Dirck’s double portrait of his parents as a commemorative and memorial family portrait in a religious context, I suggest re-evaluating Dirck’s painting as a visual presentation of his artistic identity as a portrait painter and as a proud son of a portrait painter who both successfully mastered and inherited his father’s portrait painting skills and techniques. Building on existing research, archival documentation, and iconographical analysis, it is possible to propose Jacob Cornelisz painting his wife Anna as an artistic narrative that entails Dirck’s artistic family lineage, successful mastery of his father’s studio practices, and self-identification as a prominent portrait painter.

Endnotes

1 Katherine Hoffman, “From the Renaissance to the Nineteenth Century,” in Concepts of Identity: Historical and Contemporary Images and Portraits of Self and Family (New York: Icon Editions, 1996), 25.

2 Patricia Rubin, “Understanding Renaissance Portraiture,” in The Renaissance Portrait: from Donatello to Bellini (New Haven and London: Yale University Press and The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2011), 2–25.

3 Joanna Woods-Marsden, “Part V: Habbiamo Da Parlare Con Le Mani,” in Renaissance Self-Portraiture: The Visual Construction of Identity and the Social Status of the Artist (1st ed. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998), 236.

4 The Rijksmuseum’s label description for Jacobsz’s Jacob Cornelisz painting his wife Anna showcases for Remember Me 2021 exhibition.

5 Giovanni Ciappelli, “Family Memory: Functions, Evolution, Recurrences,” 34.

6 Ann Jensen Adams, “The Cultural Power of Portraits: The Market, Interpersonal Experience, and Subjectivity,” in Public Faces and Private Identities in Seventeenth-Century Holland: Portraiture and the Production of Community (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 31.

7 P. C. Molhuysen, “Jacobsz (Dirck),” in Nieuw Nederlandsch Biografisch Woordenboek (Leiden: A. W. Sijthoff's uitgevers-maatschappij, 1911-1937), 413–14.

8 Yvonne Bleyerveld, Jacob Cornelisz (Ouderkerk aan den IJssel: Sound & Vision Publisers, 2019), xxii.

9 Henry Luttikhuizen, “Intimacy and Longing: Jacob Cornelisz van Oostsanen and the Distance of Love,” in Ut Pictura Amor: The Reflexive Imagery of Love in Artistic Theory and Practice, 1500-1700 (Boston: Brill, 2017), 533.

10 Yvonne Bleyerveld, Jacob Cornelisz, xxii.

11 Margaret Haines, “Artisan Family Strategies: Proposals for Research on the Families of Florentine Artists.” In Art, Memory, and Family in Renaissance Florence (United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 167.

12 P. C. Molhuysen, “Jacobsz (Dirck),” 413–14.

13 Margaret Haines, “Artisan Family Strategies: Proposals for Research on the Families of Florentine Artists,” 170.

14 Ann Jensen Adams, “Family Portraits: The Private Sphere and the Social Order,” 114.

15 Yvonne Bleyerveld, Jacob Cornelisz, xxii.

16 Yvonne Bleyerveld, Jacob Cornelisz, xxii.

17 Yvonne Bleyerveld, Jacob Cornelisz, xxiv.

18 Joanna Woods-Marsden, “Part I: The Intellectual, Social, and Psychic Contexts for Self-Portraiture,” in Renaissance Self-Portraiture: The Visual Construction of Identity and the Social Status of the Artist (1st ed. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998), 25.

19 Joanna Woods-Marsden, “Part V: Habbiamo Da Parlare Con Le Mani,” 236.

20 Diane Wolfthal, The Beginnings of Netherlandish Canvas Painting, 1400-1530 (Cambridge, CB: Cambridge University Press, 1989), 6.

21 The Rijksmuseum, “Remember Me,” 2021.

22 Joanna Woods-Marsden, “Introduction: The Social Status of the Artist in the Renaissance,” in Renaissance Self-Portraiture: The Visual Construction of Identity and the Social Status of the Artist (1st ed. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998), 4.

23 Joanna Woods-Marsden, “Introduction: The Social Status of the Artist in the Renaissance,” 4.

24 P. C. Molhuysen, “Jacobsz (Dirck),” 413–14.

Author Bio

Melody is a recent graduate of McGill University’s Bachelor of Arts Honours. She double-majored in art history and international development studies with a minor in communication studies. Her study primarily focuses on European and East Asian visual art, history, and culture from the early modern period to the contemporary. She is also interested in today’s issues and debates surrounding ethnic & national identities, humanitarian works, global policy makings, East Asian politics, and media practices & infrastructures in a critical social, cultural, and political lens. Currently, Melody is a master student at University of Amsterdam and specializes in the arts of the Netherlands. She is eager to continue exploring current theoretical and methodological questionings and challenges in the field of art history, a discourse that addressed prevailing aesthetic, intellectual, and social issues across different times, places, and cultures.