In a World with a Nuclear North Korea, Can We Question the Power of Nuclear Non-Proliferation?

By M. Ethan Johnson

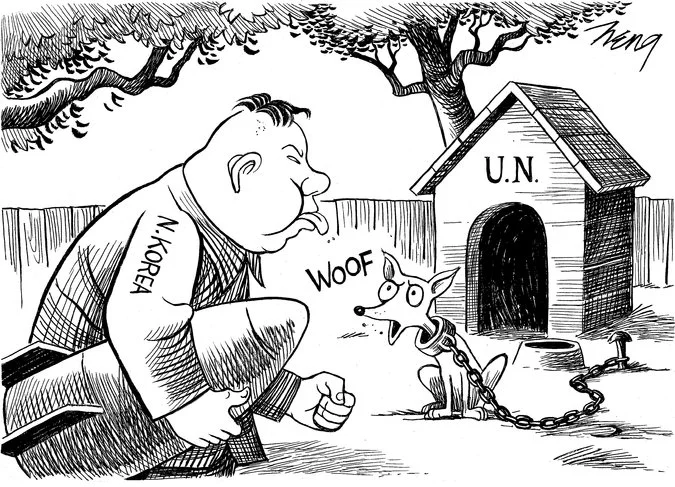

Image courtesy of Heng, Op-ed contributor for the New York Times

It’s been nearly two weeks since the Hermit Kingdom declared that it had successfully launched and detonated a hydrogen bomb—much to the surprise and dismay of the international community.

Major news outlets have argued, minimalized, and debased the plausibility of a nuclear Democratic Republic of North Korea, but let’s consider such a world.

Though the DPRK’s big brother, China, has publically deplored the North’s actions, relations between the two nations will remain strong. Two interesting variables in this highly combustible region are at play here: primarily, the recent economic stress the Chinese state has been experiencing, and, secondly, the international pressure applied over the East China Sea disputes. While, historically, China has been a holdout on the strict economic sanctions employed by much of the western world, their external pressures and faltering economy could prove a key in the future of the Hermit Kingdom. Without the fiscal backing of a strong China, a nuclear North Korea could be more unpredictable than ever.

The United States, not surprisingly, responded with a show of strength: sending the notorious nuclear capable B-2 and B-52 bombers within launching range of the North. “This was a demonstration of the ironclad U.S. commitment to our allies in South Korea, in Japan, and to the defense of the American homeland,” Admiral Harry Harris Jr., commander of the United States Pacific Command, has said. If a nuclear North were to successfully launch a missile, presumably toward non-nuclear South Korea who has a longstanding bilateral security agreement with the United States, they would face full military might of the United States, and the Japanese—not to mention the several European nations whose economic interests or national security would be at stake.

While six party talks between China, Japan, South Korea, Russia, the United States, and North Korea have been in a deep freeze since 2009, China has been calling for their resumption since October of last year. The Chinese call is most remarkable because deescalating a potential military conflict would have to be coordinated by the Chinese. If Xi Jinping, China’s president, were willing to negotiate on the behalf of the North Koreans—which could be indicated by the Chinese call for resuming talks—then de-escalation could be possible. The ability or willingness of the Chinese to play ball, however, is rather undeterminable with their interdependency on their Russian allies, the American economy, and international pressure.

The South Korean Government responded strongly by resuming its broadcast of propaganda via loudspeaker across the demilitarized zone. While the response is largely symbolic, it could quickly escalate the already tense situation: perhaps eliciting a North Korean military response. A successful nuclear attack on the South would be devastating. Loss of life, culture, and ingenuity would be incalculable. The entire international community would be in shock. Economies crippled. This would be the critical mark in global politics: dragging the most powerful countries into the largest war in seventy years.

With Japan rearming for the first time since the Pacific War, and the sizeable American military presence in the east, the ability to mount and mobilize is quite feasible.

If, however, Putin’s Russia were to covertly support the Chinese and DPRK—though he has joined president Obama in calling for a tough global response—the narrative could take a much bleaker turn. So what does Russia have to gain from a nuclear North Korea? With Putin’s recent shows of power, a war in the far East could distract international focus on the lucrative, decades old wars waged on the Middle Eastern nations—allowing him to cash in on his longstanding support of the Assad regime for a bigger cut of Syrian oil.

Nations, much like the men and women who run them, tend to possess a hint of irrational spirit. Tensions, emotions, and marked pasts play major roles in national decision making. Kim Jong-un isn’t immune to such an irrational spirit: perhaps minimalizing his fear of mutually assured destruction. A nuclear North Korea forces us to beg the question: is nuclear non- proliferation an effective deterrent in such a world? Perhaps not.

Sources can be found embedded in the text.

Cover image by Stephan