A "Prayer for Ukraine:" Music and National Identity

Evan Chan

Introduction

The Ukrainian Identity From 1848 and Onwards

In this analytical and comparative study, I analyze Anna Lapwood’s transcription of Mykola Lysenko’s Prayer for Ukraine (1885) and compare it to John Romano’s recent arrangement for the United States Air Force Band. I further examine the extramusical narratives of cultural identity and highlight this hymn as a symbol of Ukrainian independence. The Ukrainian struggle for independence has lasted for centuries. Present-day Ukraine was formerly ruled by the Romanovs–later the Soviet Union–and the Habsburgs (1760-1991), where many Ukrainians were assimilated into other cultures. The nineteenth century, however, saw a series of revolutionary uprisings. As Paul Kubicek states, “toward the end of the nineteenth century, Ukrainians began to experience an important ‘ideological conversion,’ as the cultural intelligentsia, which had been growing throughout the nineteenth century, abandoned its previous ethnic self-destination as Rusyns, or Ruthenians, and began using a new moniker, Ukrainians.”[1] The rise of the Orthodox Church, the increase of scholarly publications, and the establishment of Ukrainian educational institutions became important vehicles for creating a unified Ukrainian identity.[2] To use Kubicek’s term, this “Ukrainian awakening” would continue to last throughout the twentieth century which saw Ukraine established as a nation–following the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991.[3]

Although the nineteenth century saw an uprising of the Ukrainian nationalist movement, local authorities often suppressed cultural expression. In the Russian regions, most of the Ukrainian population lived in the Dnieper region with a governance structure that kept people under the shadow and surveillance of the Tsar.[4] In Austria, the remaining Ukrainian population occupied regions such as Galicia. Paul Magosci remarks that in 1848, “the year indeed witnessed the rebirth of all aspects of Ukrainian life in lands under the Habsburg sceptre.In that year alone, Ukrainians established their first political organization, their first newspaper, their first cultural organization, and their first military units in modern times.”[5] The Revolution of 1848 remains an influential set of events that would continually solidify Ukrainian identity and independence.

Mykola Lysenko and Music’s Role in Ukraine’s Cultural Identity

Music has long been a voice for nationalist movements throughout Western Europe. From present-day Finland to Germany, many nations owe their cultural and political unification to musical composition, culture, and criticism. In the case of Finnish composer Jean Sibelius (1865 – 1967), his compositions contributed to unifying Finland while it remained under oppression by the Russian Empire. Similarly in Ukraine, musical activities continued throughout the centuries even under extensive censorship. Many forefathers such as Mykola Lysenko (1842 – 1912) aimed to use music to curate a national identity.

Mykola Lysenko was a creative ethnomusicologist and composer who received formal classical training but remained fascinated by the Ukrainian folk tradition.[6] Lysenko’s compositional collection includes operas and symphonies, but he also compiled countless folk songs in volume publications. He often took folk melodies and used them as a basis for compositions in the classical-romantic idiom.[7] In 2001, Filenko and Bulat noted that Lysenko’s immense dedication to the Ukrainian repertory is the result of “his view as music as a vehicle for the promotion of national identity and populist agenda permeates his writings and activities.”[8] They further posit that he “viewed Ukrainian traditional music as a device for sustaining ethnic identity.”[9] Even though many of Lysenko’s publicationswere censored by Russian surveillance, authoritarianism did not stop him from pursuing culturally controversial musical activities at the time.[10] He established the first national opera, founded national music education, and “trained a generation of musicians who later became Ukraine’s musical elite.”[11] For Lysenko, music was clearly a form of cultural preservation and expression.

Prayer for Ukraine in the Present Day

As part of the movement for cultural preservation and expression, Lysenko composed Prayer for Ukraine (Molytva za Ukrainu) in 1885, using text from poet Oleksandr Konysky (1836 – 1900).[12] Konysky himself was a writer and literary critic devoted to Ukrainian culture and literature. Similar to Lysenko, Konysky’s works were censored, and he was later exiled from Russia in 1863.[13] Originally arranged for women’s choir and piano accompaniment, the censor deemed Lysenko’s composition as “unconditionally prohibited noted January 9, 1886.”[14] The music itself is relativelysimple, consisting of a narrow melodic range and smooth chorale voice-leading. However, the text was considered problematic, as it speaks to the divine and prays for the protection and freedom of Ukraine. Today, this piece remainsthe spiritual anthem of Ukraine and is one of Lysenko’s most well-known compositions. It has become a musical symbol that speaks to the freedom and independence of Ukraine as a sovereign nation, even in the twenty-first century.

On February 23, 2022, Russian forces declared war on Ukraine after a series of explosions.[15] This continues to be an ongoing conflict and a significant world event, given the threat of this war on Ukraine’s culture, sovereignty, and independence. With immediate action, the United Nations and most of the Western world pledged to support Ukraine.[16] In the musical world, ensembles from across the globe began performing Ukrainian compositions–such as the State Anthem of Ukraine by Mykhailo Verbytsky–to stand in solidarity with the people of Ukraine. Across social media platforms and online video services, recordings of Lysenko’s Prayer for Ukraine also quickly surfaced. Organist Anna Lapwood released a four-part transcription and translation, which in part contributed to the widespread performance of this hymn.[17] Many ensembles also began performing their own renditions and composing new arrangements.

Even with the widespread use of Prayer for Ukraine in North America, there remain few theoretical and analytical discussions in the English-speaking world. For example, it is difficult to find an analysis of the text or hymn setting. Furthermore, the vast array of online performances with different traditions, renditions, and interpretations remains undiscussed in music theory. Taking a theoretical framework, I analyze Anna Lapwood’s transcription of Mykola Lysenko’s Prayer for Ukraine and compare this hymn setting to a recent arrangement (The full analysis of Lapwood’s transcription is found in Appendix A).[18] Through this critical and comparative study, I will illustrate one example of how Lysenko’s hymn has been transformed through orchestration and formal techniques.[19] Discussions of how this hymn fits in with Ukrainian culture and nationalistic identity will be later expanded upon in the discussion for further musicological research.

Discussion

Mykola Lysenko’s Hymn Setting

Mykola Lysenko’s setting of Prayer for Ukraine demonstrates a cosmopolitan style of composition. His trainingthroughout Europe and his passion for Ukrainian art and culture often led to compositions that are classical by nature, but Ukrainian by heart. He uses many conventional voice-leading techniques which follow the contrapuntal (the musical layering of multiple melodies or voices) traditions of J.J. Fux and J.S. Bach. He even employs an ABAC structure that follows the global tonic of C Major with hints of secondary key areas. However, his adaptation of Konysky’s Ukrainian text is an element of nationalistic identity. This text speaks to the freedom and protection of Ukraine, where Lysenko decided to include this text at a time when cultural surveillance prohibited such action.

Lysenko’s setting of Prayer for Ukraine follows many of the standard techniques in chorale voice leading. The many uses of passing tones (notes that fill the gaps between two notes), pedal tones (notes in the bass that are repeated for a long duration), and neighbor tones (notes that are in close proximity to the one preceding and proceeding it), preserve smooth voice leading. The passing tones in particular strictly observe the rules of Fuxian counterpoint by moving in parallel imperfect consonances (intervals of thirds and sixths). Furthermore, the pedal tones often follow the same rhythm as the melody in the soprano voice. This allows the pedal tones to be articulated and prevent them from muddling the upper voices. Many subsidiary harmonies arise as a result of all this smooth contrapuntal voice-leading. For example, a Schenkerian sketching (voice-leading graphs highlighting the primary melodic line) of m. 21-22 reveals an underlying dominant-tonic harmonic progression, even though there are a variety of surface-level subsidiary harmonies (figure 1).

The structure of the chorale follows an ABAC form with relatively simple harmonies. The A sections largely revolve around C Major, while the B section introduces the first glimpse of the relative minor key. The final C section hybridizes these two key areas by centering around C Major, but it also includes statements of the relative minor through tonicization (a brief venture into secondary key areas). Lysenko’s setting also aligns with the structure ofKonysky’s text. Most notably, “Protect our beloved Ukraine” is the only line of text that reappears.[20] As such, Lysenko has decided to make both these instances of the text part of the principal theme–or the A section.

USAF and the Singing Sergeants — Arrangement by John Romano

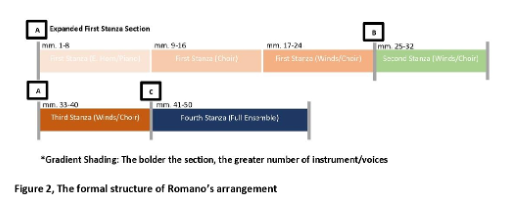

The United States Air Force Band (USAF) and the Singing Sergeants present a concert band-choir arrangement that expands upon Lysenko’s setting for choir. This in-house arrangement is open source with the bandstration by John Romano.[21] Published on March 9, 2022, this tribute video to the Ukrainian people is interspersed with a variety of picturesque photos representing Ukrainian people, landscapes, statues, and flag colors.[22] Romano expands Lysenko’s original hymn setting, employing a wide range of instrumental timbres and motivictechniques to develop musical continuity. He even develops the form of Lysenko’s setting by repeating the first stanza three times (figure 2). Although Romano retains Lysenko’s harmonic framework and melodic contour, the addition of instrumental countermelodies and occasional decorative figures possibly implies extramusical narratives.

The “Domino” Effect in the First Stanza

Musical expansion and variation of Lysenko’s setting is first seen when the first stanza is repeated three times with different accompaniment textures and phrasing gestures. By using different groupings of instruments, the repeated theme avoids textural monotony. This is important, as the overuse of the exact same repetitive musical material can lead the music into a form of stasis. The English horn first introduces the chorale melody,while the piano accompanies it by playing the full chorale setting. The choir then sings Lysenko’s setting and Konysky’s text with no instrumental accompaniment. In the final restatement, the full ensemble and voices join in unison. In terms of phrasing decisions, the choir takes a different approach than the English horn soloist. While the English horn uses four-measure phrases, the choir follows the common performance practice of two- measurephrases.

Overall, the instrument voices are slowly added to create a “domino” effect in the orchestration (figure 3). After the English horn-piano duet, the singers establish a grander sound because the recording engineer masters this section to be more prominent. In the final restatement, almost the entire concert band is added to the orchestration. In this section, the upper-reeded woodwinds double the chorale voices, while the bassoon, French horn, and tuba add countermelody and accompaniment textures. In one setting after the next, the expansive use of instrumentation, and fluctuating dynamics helps develop increasingly larger volumes of sound.

Continuity Through Instrumentation

Contrary to the building-up of sound through the use of different instruments, Lysenko’s original setting regularly uses rests to provide moments of silence in between phrases. Romano’s arrangement eliminates this silence by using instrumental textures and motives to further create musical continuity. In this context, continuity is defined as the consistent sounding or flow of musical material, often with little to no moments of rest or silence. For example, the French horn and tuba in m. 17 hold onto the long tones with occasional passing notes. Since the brass serves a droning function, the articulative quality of the other voices is often blurred. The droning also makes it difficultfor any moment of complete silence to be heard.

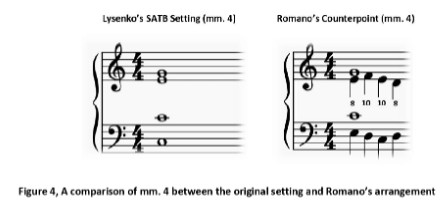

In the statement of the second stanza, Romano develops a fuller concert band sound by adding flute, oboe, and timpani to the mixture. He is careful to avoid the use of the trumpet and saxophones by saving these timbres for the finale. Furthermore, the subtly rolled fourths of the timpani provide a militaristic feel that provides forward momentum in the dramatic transitions. In the realm of motives, passing notes (notes that fill the gaps between two notes) and melodic figures are often used to connect disjunct leaps (a large interval between two notes). The duet on m. 4 contains a first-species counterpoint to avoid melodic stasis (notes or musical activity that does not move; stagnant) (figure 4). Although Romano creates a melodic motion that leads into the next four-measure phrase, the octaves between the alto-bass voice create a hollow-sounding lead-in. Nonetheless, musical continuity is still achieved by droning and passing tones.

The American Countermelody

In addition to composing-in musical continuity, Romano also includes a newly composed countermelody. In m. 33, the restatement of the opening melody accompanies a countermelody with similar melodic and rhythmic characteristics. This countermelody soars through the ensemble due to the piccolo’s poignant sound and high tessitura (the range of musical pitches). In this performance, the piccoloist’s rustic-edge resembles a military fife. This militaristic style is also reflected in the countermelody since the melodic contour resembles the tune of William Steffe’s Battle Hymn of the Republic. The relatively stepwise ascent and descent about the apogee (the highest note in the melody) and triadic outlines (the outlining of three-note chords) make this comparison apparent. Even though the rhythmic profiles do not match, a melodic contour analysis reveals otherwise (figure 5). This civil war-style tune represents the American military style/identity which is paired with Lysenko’s Ukrainian classical hymn.Although it is beyond the scope of this article to discuss deep musical hermeneutics or Romano’s compositional intentions, there are possibilities of an extramusical narrative here. One possibility for further exploration could be the expression of American identity within a Ukrainian hymn tune. Another speculative interpretation could be that the United States military is musically showing their stance in solitude with the Ukrainian people.

A Grander Arrival

After the ending of the American countermelody, Lysenko’s setting establishes a grand finale at the end of the chorale. Expanding upon this interpretation, Romano presents an even grander approach by eliminating all soft dynamics and making full use of the percussion section. In m. 41, the trumpets, saxophones, and full percussion enter to create a more direct and accented sound, while the cymbals emphasize this arrival. It is also at this moment thatRomano takes a different interpretive approach. While Lysenko’s hymn returns to pianissimo to create space to develop a crescendo, Romano’s setting reaches forte with the cymbals clashing every measure to signal an important arrival point. With the final moment of arrival being in m. 45, Romano has created an arrival before the arrival.

Following the section of m. 41, the fortissimo section in m. 45 is performed with an accented tone of proclamation followed by the broad and tenuto-style accompaniment. The orchestra is rearranged with almost all of the instruments doubling the voices of the chorale setting. With many instruments and voices in unison, the performers play in a proclamatory style. The final authentic cadence is also highlighted by ‘lifting’ gestures of passingtones not prevalent in Lysenko’s setting. The conductor additionally chooses to add an extreme ritardando at the end, amplifying the grandiose effect.

Conclusion

This article presents an analysis and cross-comparison between Mykola Lysenko’s A Prayer for Ukraine and John Romano’s arrangement. The themes and musical structures follow the structure of Konysky’s poem, creating an ABAC form. Upon comparison with Romano’s arrangement, several distinctions become noteworthy. First, although Romano retains most of the original setting, he expands the formal structure. The first stanza is repeated three times with different orchestrations to develop a “domino” effect. Furthermore, the use of varying instrumental textures helps achieve musical continuity and produces dramatic expressions not possible in an acapella setting. This preliminary study can be taken further in the realms of musicological research and hermeneutics. I primarily focused on the theoretical aspects of Lysenko’s setting, however, a more in-depth analysis of the relationship between the hymn tune and Konysky’s text may reveal certain aspects of Lysenko’s compositional style. For example, one inquiry may investigate how the word “Ukraine” is melodically and harmonically illustrated, or why hints of the relative minor are introduced when the text discusses the theological concepts of mercy and grace.

In summary, this study brings to light analysis of Lysenko’s hymn and explores one of the many examples of compositional transformation using his setting. Romano’s arrangement stems from the United States Armed Force’s involvement in the Russia-Ukraine war. Apart from the humanitarian, weapons, and physical aide from the United States, this musical arrangement can also be seen as another form of support—one of morale and solidarity. Further replications of this study can begin to explore the large repertory of arrangements created in other countries and settings since the outbreak of the Russian-Ukraine war.

Endnotes

[1] Paul Kubicek, The History of Ukraine: History of Ukraine, (Westport, USA: ABC-CLIO LLC, 2008), 71, Retrieved from Ebrary Collections Ebook.

[2] Kubicek, The History of Ukraine, 71-73.

[3] Kubicek, The History of Ukraine, 72.

[4] Paul Magosci, A History of Ukraine, (Seattle, USA: University of Washington Press, 1996), 309-313, Retrieved from Ebrary Collections Ebook.

[5] Magosci, A History of Ukraine, 406.

[6] Taras Filenko and Tamara Bulat, The World of Mykola Lysenko: Ethnic Identity, Music, and Politics in Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Century Ukraine, (Edmonton, Canada: Ukraine Millennium Foundation, 2001), 10.

[7] Filenko and Bulat, The World of Mykola Lysenko, 10.

[8] Filenko and Bulat, The World of Mykola Lysenko, 10.

[9] Filenko and Bulat, The World of Mykola Lysenko, 10.

[10] Filenko and Bulat, The World of Mykola Lysenko, 135.

[11] Filenko and Bulat, The World of Mykola Lysenko, 9.

[12] Filenko and Bulat, The World of Mykola Lysenko, 418.

[13] Ivan Koshelivets, “Konysky, Oleksander,” in Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine (Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies, 1988 original). https://www.encyclopediaofukraine.com/display.asp?linkpath=pages%5CK%5CO%5CKonyskyOleksander.htm.

[14] Filenko and Bulat, The World of Mykola Lysenko, 418.

[15] Anna Renton et al., “Ukraine Says It Was Attacked through Russian, Belarus and Crimea Borders.” CNN CableNews Network, February 24, 2022. https://www.cnn.com/europe/live-news/ukraine-russia-news-02-23-22/h_82bf44af2f01ad57f81c0760c6cb697c (Accessed December 12, 2022).

[16] United Nations, “Ukraine,” UN News: Global Perspective Human Stories, Accessed December 11, 2022, https://news.un.org/en/focus/ukraine.

[17] Anna Lapwood, Twitter post, March 2022, 2:40 AM, https://twitter.com/annalapwood/status/1498578901483900928?lang=en.

[18] Since Lapwood’s transcription is the main commercially available sheet music, I will use this as the “critical edition”for analyzing Lysenko’s hymn.

[19] It is important to select an arrangement that retains the traditional elements of Lysenko’s setting but deviatesthrough a variety of compositional processes. One of the most popular recordings that have surfaced on YouTube is the USAF and Sing Seargent’s Bandstration arrangement. This choir-concert band hybrid retains the choral setting but makes use of the concert band medium.

[20] Taken from the translation by Anna Lapwood.

[21] Aaron Moats, “LysenkoRomano_PrayerforUkraine_00Score.pdf,” Box, March 11, 2022, https://usaf-band.app.box.com/v/prayer-for-ukraine/file/929864073318.

[22] The United States Air Force Band, “‘Prayer for Ukraine’ (Молитва за Україну) - The United States Air Force Bandand Singing Sergeants,” YouTube Video, 3:44, March 9, 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=glL_mWmzXoM&ab_channel=TheUnitedStatesAirForceBand.

References

Filenko, Taras., and T. P. Bulat. The World of Mykola Lysenko: Ethnic Identity, Music, and Politics in Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Century Ukraine. Edmonton, Canada: Ukraine Millennium Foundation, 2001.

Koshelivets, Ivan. “Konysky, Oleksander.” In Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine. Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies, 1988 (original). https://www.encyclopediaofukraine.com/display.asp?linkpath=pages%5CK%5CO%5CKonyskyOleksander.htm

Kubicek, Paul. The History of Ukraine: History of Ukraine. Westport, USA: ABC-CLIO, LLC, 2008. Retrieved Fromhttp://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/umanitoba/detail.action?docID=617383.

Lapwood, Anna. Twitter post. March 1, 2022, 2:40 AM. https://twitter.com/annalapwood/status/1498578901483900928?lang=en.

Magocsi, Paul R. A History of Ukraine. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1996. Retrieved fromhttps://books-scholarsportal-info.uml.idm.oclc.org/en/read?id=/ebooks/ebooks0/gibson_crkn/2009-12-01/6/417660#page=1

Moats, Aaron. “LysenkoRomano_PrayerforUkraine_00Score.pdf.” Box. March 11, 2022. https://usaf-band.app.box.com/v/prayer-for-ukraine/file/929864073318

Renton, Adam, Rob Picheta, Ed Upright, Melissa Macaya, and Maureen Chowdhury. “Ukraine Says It Was Attacked through Russian, Belarus and Crimea Borders.” CNN Cable News Network, February 24, 2022.https://www.cnn.com/europe/live-news/ukraine-russia-news-02-2322/h_82bf44af2f01ad57f81c0760c6cb697c (Accessed December 12, 2022).

The United States Air Force Band. “‘Prayer for Ukraine’ (Молитва за Україну) - The United States Air Force Band and Singing Sergeants.” YouTube Video, 3:44. March 9, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=glL_mWmzXoM&ab_channel=TheUnitedStatesAirForceBand.

United Nations. “Ukraine.” UN News: Global Perspective Human Stories. Accessed December 11, 2022.https://news.un.org/en/focus/ukraine

Evan Chan

Evan Chan is a direct-entry PhD student in music theory at the University of Toronto supported by the Manitoba Arts Council and the Ontario Graduate Scholarship. His interdisciplinary interests include form in Chinese-Western music, music cognition, technology in music theory pedagogy, musical theology, and neurologic music therapy. He holds a BMus in Music History (Gold Medal, 2023) from the University of Manitoba, where he focused on Gregorian chant and pursued instrumental studies with Laura Loewen, David Moroz, Darryl Friesen, and Steven Dyer. In the community, Evan served on the board of directors for Winnipeg Contemporary Dancers and was a founding member of several non-profit organizations in Manitoba. Recently, he was awarded the Honour 150 Medal by the Government of Manitoba, for exemplary service and leadership to the community. In his spare time, you can often find him playing the organ at Trinity College and Wycliffe College, serving as a marriage commissioner, swing dancing with UT-Swing, or searching for the new food hotspots in Toronto!