Sexism in American Art Museums

By Nicole Corrigan

In the 1960s, the second wave of feminism came crashing over America and led to the criticism of many cultural institutions that had long been bastions of sexism. Even the art museum, long seen as a holy temple above such politics, was not spared from the feminist critique. The goal was to transform museums into establishments that promoted inclusivity and multiple narratives. As time has passed and feminism has moved from the second to third and, some argue, fourth wave, there are some who say that feminism has done its job and there is no need for it any longer. As pleasant as that may sound, it is unfortunately far from the truth, especially in the world of museums. Despite several decades of feminist critique, American art museums still reinforce a hierarchy of gender that ultimately privileges the male gaze and the male artist. Before delving into the ways that art museums have yet to make significant progress in becoming more gender inclusive, it would be beneficial to explore the ways in which it has traditionally been exclusive. Historically, female artists have been absent from permanent collections; there has been a dearth of solo exhibitions by women; and the ways women are presented in artwork have ultimately caged them and made them subjects to the male gaze.

One of the largest complaints leveled by feminists against art museums is the lack of representation of women artists in permanent collections. Katy Deepwell explains, “Until the late 1960s, the presence of women artists in most major museum collections would lead one to bethink that women existed only as a minority of practitioners. Their work formed less than 10-20 percent of most major art collections…” (Deepwell 67). This was the trend throughout most American art museums.

Those who defended the lack of female representation in museums often claimed that there simply were no “great” female artists, and that it would be destructive to the integrity of the museum to hang mediocre works, merely because they were created by women. However, with some research, it becomes obvious that there is a plethora of works from women, all of them of artistic merit, that have simply been ignored over the years. In their stead hung the regular litany of “genius” male artists that the public is already well acquainted with.

The permanent collections are not the only place in the art museum where women artists have been historically underrepresented. Deepwell goes on to say, “until the 1980s, solo exhibitions of women artists were rare events” (Deepwell 67). Solo exhibitions are events that often showcase the art of more modern artists. While one could again make the argument that there simply have not been enough female artists for these shows, it is quite easy to disprove such a statement. Since the 1950s, the number of female artists has been growing and as of 2009, almost half of all working artists in the United States are women, so there are plenty of women artists to choose from when planning a solo exhibition (Condon). This has been the case for several decades now. It then stands to reason that the only reason women have historically been ignored for solo exhibitions is because museums, intentionally or not, have picked men instead.

Outside of the representation of women artists, feminists have found much to critique in the way women are displayed in the very artwork hanging on the walls of museums. Perhaps the most blatant example of this problematic display is the prevalence of the female nude in art museums. It would be entirely irrational to argue that nudity in paintings is a sexist practice that needs to be eradicated; the nude figure in art is a long tradition often used to showcase the beauty of the human form. However, it does become problematic when one discovers that as of 1989, 85% of the nudes displayed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art were females (Guerilla Girls). When such an overwhelmingly large proportion of nudes are female, it is impossible to merely accept the artwork at face value. In exploring the ways that the people view nudity in art, John Berger explains that often times, the nudity of a female is not expressing the feelings of the subject—instead it is expressing “her submission to the owner’s feelings or demands. (The owner of both woman and painting)” (Berger 51). He continues, “the ‘ideal’ spectator is always assumed to be male and the image of the woman is designed to flatter him” (Berger 52). With this in mind, the female nude is no longer an experience in aesthetics—it is an experience in domination and consumption. It is this experience that feminist critiques attempt to dismantle.

With issues as blatant as these plaguing art museums and the decades of criticism they have garnered, it would seem likely that there would have been extreme overhaul to collections, policies, exhibitions, and display practices. In spite of it all, however, the gender hierarchy still stands strongly in art museums. Gail Levin notes, “Museums today remain burdened by a centuries-old commitment to maintaining a master narrative that privileges white men” (Levin 102). While there has been some improvement, there is doubtless still much that remains to be done.

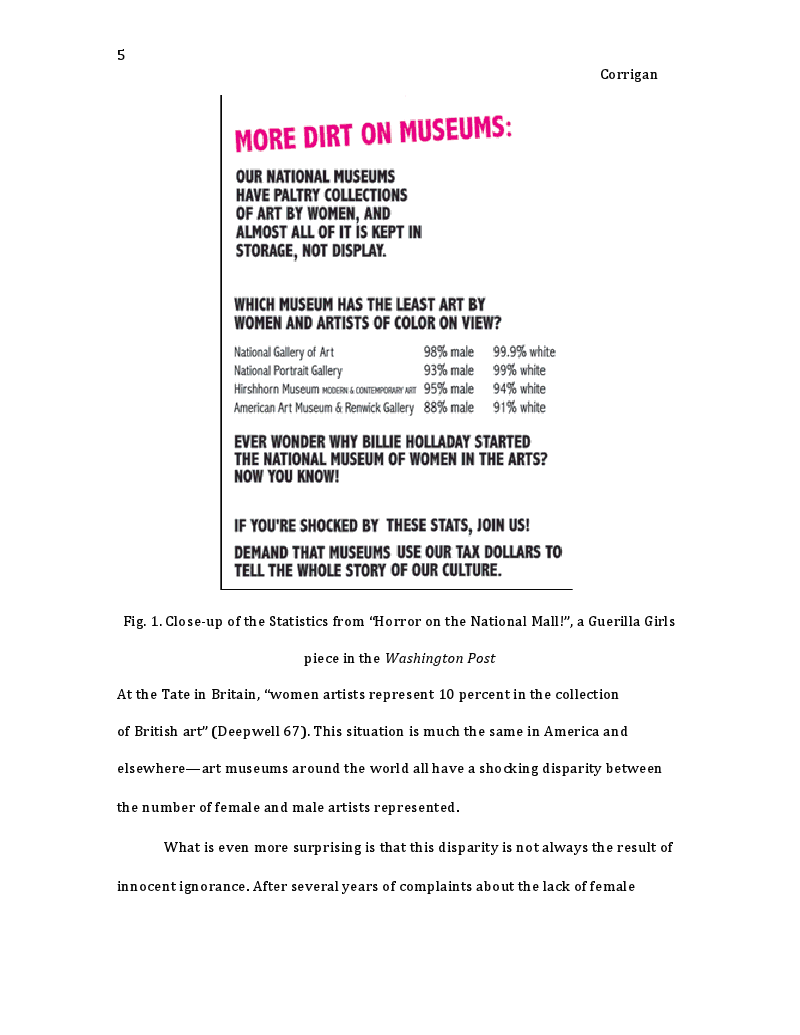

Though much attention has been called to the meager number of female artists represented in the permanent collections of museums, or at least what is displayed from those collections, little has been done to rectify the situation. The Guerilla Girls, a group of anonymous female artists dedicated to calling attention to sexism in the art world, counted the number of female artists in the modern art sections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In 1989, less than 5% of the artists were female; by 2005, this number had dropped to less than 3% (Guerilla Girls). Furthermore, the Guerilla Girls publicized the low numbers of female artists on display in the art museums of the Smithsonian in the April 22, 2007 issue of the Washington Post (see fig 1).

Fig. 1. Close-up of the Statistics from “Horror on the National Mall!”, a Guerilla Girls piece in the Washington Post

At the Tate in Britain, “women artists represent 10 percent in the collection of British art” (Deepwell 67). This situation is much the same in America and elsewhere—art museums around the world all have a shocking disparity between the number of female and male artists represented.

What is even more surprising is that this disparity is not always the result of innocent ignorance. After several years of complaints about the lack of female artists in their permanent collections, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York City raised the hopes of many when they announced they were going to rethink their installations and “investigate ‘multiple narratives’” (Saltz). The museum was obviously aware of the problem and appeared to be taking action to rectify it. By the end of 2006, when the reorganization and remodeling of its galleries were completed, it became clear that the situation largely had stayed the same. A count done by Jerry Saltz, an American art critic, revealed, “Of the 135 artists installed on these floors [housing the permanent collection], only 19 are women, 6%” (Gender Disparity in MoMA’s Collection). The museum knew that its collection was lacking and willfully abstained from taking action. Apparently, decades of feminist critique meant very little in this situation.

Some museums claim that they simply lack enough works by female artists in the collection they choose from to display and have insufficient funds to acquire any. This is a reasonable argument; after all, museums are often restricted by tight budgets. Yet how often is this lack of female artists in their collection actually a lack of knowledge of what is in their collection? While working at the Whitney Museum of American Art, Gail Levin discovered the museum once held a large cache of artwork by Josephine Nivision Hopper, wife of the heavily acclaimed artists, Edward Hopper (Levin 94). Instead of making use of this large collection, the museum instead gave away many of the paintings, without recording information about the donations, and relegated the rest to anonymity in their collection (Levin 94). As time passed, most employees of the museum forgot about the paintings and eventually most did not even realize they were there. Levin remarks, “While some female artists have fared better [than Jo Hopper], the works of many twentieth-century women remain obscured by their husbands’ fame as artists, and museums collude in this practice” (Levin 93). This occurrence of a museum willing a female artist’s work into obscurity raises an important question—how many other museums are doing the same, while simultaneously claiming that it is impossible to display more female artists? If an institution as prestigious and trusted as the Whitney is guilty of such a practice, it stands to reason that this could be a common practice.

It is not just in the permanent collections of museums, however, that women artists still face discrimination; there is also a great disparity between temporary solo exhibitions of men and women artists. As previously mentioned, it is true that progress was made in this area of museum display; in the 1980s, solo exhibits of the work of women artists finally became something more than an anomaly. Feminist artists, such as Judy Chicago and Cindy Sherman, have their artwork featured in temporary exhibitions in some of the most prestigious art museums in the country. Having these exhibits by female and even feminist artists, some would contend, is proof that feminism’s job in the art museum is over. While it is true that the inclusion of female solo exhibits is a large step forward, it is far from enough.

Solo exhibitions in art museums are still troublesome because the sheer difference in numbers between the exhibitions of male and female artists is staggering. From 2002 to 2012 in the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, there were ninety-two solo exhibits for male artists as compared to only twenty-eight solo exhibitions for female artists (MoMA Exhibitions). This means that for all solo exhibitions, only 23% of them were of female artists; for every solo exhibition for a female artist, there are 3.3 shows for male artists. Intriguingly enough, in 2007, the year of the highest disparity between male and female solo exhibitions (seventeen for men and one for women), there was a temporary exhibit called “Documenting a Feminist Past: Art World Critique.” According to MoMA’s website, “This exhibition of material from The Museum of Modern Art Library, the Museum Archives, and the collection documents feminist critique of art institutions from 1969 to the present” (Documenting a Feminist Past). This seems indicative of the situation in art museums: feminist critiques exist and are acknowledged, but have not led to significant changes.

The numbers for solo exhibitions in other art museums in the United States are no more promising than the ones at MoMA. In the past ten years, there have been thirteen solo exhibitions for female artists to forty for male artists in the Guggenheim in New York City (Guggenheim Exhibitions). In other words, only 25% of all solo exhibitions are for female artists. At the Art Institute of Chicago, there have been twenty solo exhibitions for female artists and ninety-one for male artists in the past ten years (Art Institute Exhibitions). Female artists comprise 18% of solo exhibitions. In the same time frame, only 12% of all solo exhibitions at the Metropolitan Museum of Art were for female Artists (Metropolitan Exhibitions). The largest discrepancy is at the National Gallery in Washington D.C. From 2002 to 2009, there have been two solo exhibitions for female artists, compared to sixty-one for male artists (National Gallery Exhibitions). The percentage of solo exhibitions for female artists is a miniscule 2%. Clearly, the years of feminists deriding museums for failing to showcase female artists have little effect on these prestigious institutions.

Even when there are temporary exhibitions by women artists, the effects are, as their names suggest, ephemeral. As Gaby Porter comments,

[T]hese exhibitions are, like women’s traces in the collections of museums, marginal and less enduring: the chances to learn from them may be marginalized or ‘lost’ within institutions as their circumstances change; or overlooked by other professionals because they do not recognize such short-term projects as a valid alternative (125).

The solo exhibitions of the work of women artists are transitory; eventually they will be replaced by other exhibition, presumably one displaying the work of a male artist. In that way, art museums can afford to pay lip service to feminism by holding exhibitions of feminist or female artists without having to radically change their philosophies.

Some museums will attempt to counter accusations of discriminatory displaying by proudly pointing out a Mary Cassatt or Frida Kahlo painting hanging on their walls. They are, however, contributing to fetishization of a select few women artists, without actually pushing the boundaries of their collections. Deepwell explains, “The selective presentation of and over-investment in a handful of individual women as another ‘artistic’ product in the culture industry is fueled by the popularization of their work through videos of the artist’s life, calendars, mugs, bookmarks, and gift-cards” (Deepwell 70). As a result, if one was to ask an average American to name all the female artists they could think of, the answer will almost invariably consist of Frida Kahlo, Mary Cassatt, Georgia O’Keeffe, and maybe Diane Arbus. Most could only name one or two of those artists and no more. While art museums could be educating the public on the less known female artists, they instead intensely push a limited list of crowd-pleasing female artists, which perpetuates the lack of awareness. In this way, feminist critiques have had little effect on the education art museums provide.

One attempt to solve these problems in the lack of female artists in art museums has been to establish museums exclusively devoted to the work of women artists. The National Museum of Women in the Arts’s website declares, “The idea for the National Museum of Women in the Arts grew from a simple, obvious, but rarely asked question: Where are all the women artists?” (NMWA). Indeed, the heart of the collection, acquired by Wilhelmina Cole Holladay and Wallace F. Holladay, began forming in the 1960s when this question was first beginning to be asked on a large scale (NMWA). Another American museum dedicated to female artists is the Florida Museum for Women Artists, whose mission is “to identify and promote women artists and educate the public about women in the arts” (Florida Museum). It would seem that this is an ideal solution to the disparities in major art museums.

However, this “solution” is not as idyllic as it may appear. By separating the artwork work of women into a separate museum, women artists are automatically classified as “different” from the artists in other museums. The very qualification of the art as “women’s art” separates it from men’s art. Deepwell explains this as “establishing a category known as ‘women’s art,’ in which the concept of ‘outsider’ or ‘other’ would become the mark for women artists” (Deepwell 74). This occurs because the highest measure of success throughout history has been what men have produced. As Inga Muscio says, “the standard for existence set by white men has yet to be rescinded in this age” (Muscio 206). Separating women’s art into its own museum celebrates the art of female artists while simultaneously reinforcing the division that has forced it into a distinct museum. As a result, it cannot accurately be called a “solution” to the bias towards male artists in art museums.

Not only has feminist critique failed to change this bias, it has also failed to rectify the ways in which females are displayed in artwork itself. When the Guerilla Girls recounted the number of nudes in the Metropolitan Museum in 2005, the percentage that were female was largely the same: 83%, as opposed to the 85% of 1989 (Guerilla Girls). Additionally, there is no evidence of any major art museum staging exhibitions to explore the issues of representation in these works of nude females. The labels accompanying these pieces of art have not changed to include challenges to the ways that visitors or scholars typically view nudes.

In 1913, British suffragist Mary Richardson slashed through a painting of Venus at the National Gallery in London as a protest against the way that early art museums displayed and caged women (Levin 2-3). This is perhaps one of the earliest instances of feminists protesting against the gender hierarchy of art museums. Nearly one hundred years, and several waves of feminism, later, the question still persists—is there gender equality in art museums? Disappointingly, the answer is a resounding “no.” Though much criticism of the lack of representation of female artists and the ways in which the female body is displayed have been leveled against museums, an contemporary examination of American art museums shows that little to nothing has changed. Even the establishment of separate museums for female artists cannot be called a success in the fight against sexism in art museums. What is it that keeps this hierarchy of gender so firmly entrenched in art museums? Maura Reilly, the founding curator of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum, accurately summarizes the situation: “We are all aware that institutionalized sexism has yet to be eradicated, and until ‘greatness’ can be redefined as something other than white, western, heterosexual, and unmistakably male, we still have quite a battle ahead of us” (Butler, et al. 32). Until the words “genius” and “masterpiece” are no longer automatically synonymous with “male,” then art museums will continue to privilege the male artist and the male gaze to the detriment of women.